National EMS Education Agenda for the Future

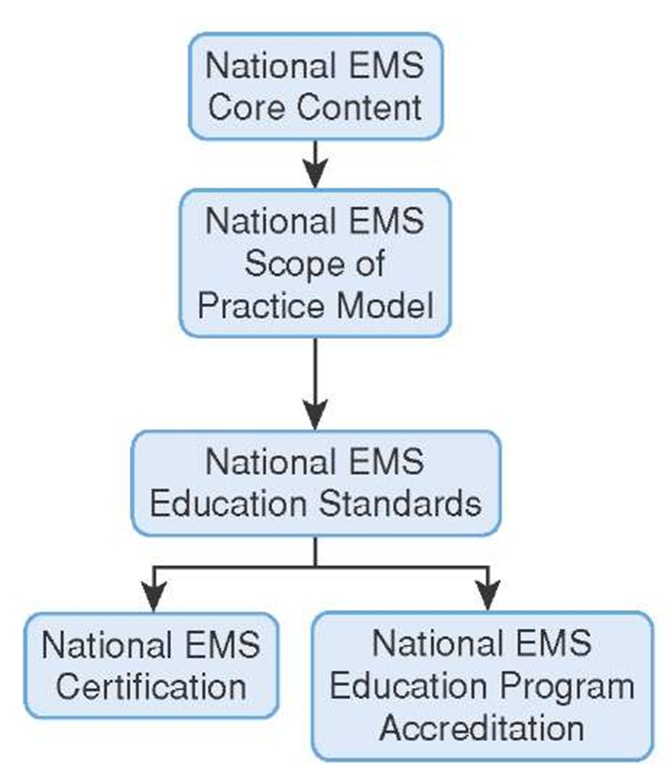

In 1996 the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration convened a meeting of over 30 EMS organizations with the intent of implementing the educational portions of the EMS Agenda for the Future. The results of that meeting became known as the national EMS Education Agenda for the Future.29 The Education Agenda set out to describe how all EMS providers, including Paramedics, would be prepared for service in EMS by following a systems approach. The National EMS Education Agenda, a systems approach, established five components that incorporated the essential elements of an educational system and how these elements interacted in a system (Figure 2-8).

The first component was the National EMS Core Content. The core content defines the entire universe of disorders, diseases, syndromes, and skills that an EMS provider might encounter and for which he would be expected to provide emergency care (i.e., the domain of EMS practice). Naturally, EMS physicians had a lead role in defining the domain of EMS practice. To the extent possible, the core content tried to include those practices that had strong evidence to support them or those that appeared in the 2004 practice analysis conducted by the National Registry of EMT.

The second component of the EMS Education Agenda for the Future was the National EMS Scope of Practice (NEMSSOP) model.30 The scope of practice defines and divides EMS into four groupings. The National EMS Scope of Practice, created under the leadership of the National Association of State EMS Officials (NASEMSO), formerly known as the National Association of EMS State Directors (NAEMSD), clearly defines four levels of EMS providers. More importantly, it identifies the knowledge and skills required for each level (i.e., what is the scope of practice for that level within the domain of EMS practice).

Figure 2-8 The five essential elements of the EMS educational system.

One advantage of a national SOP is that there is a standardization of EMS providers of four levels. The four levels of EMS providers described in the NEMSSOP include the emergency medical responder (formerly the certified first responder), the emergency medical technician (formerly the emergency medical technician-basic), the advanced emergency medical technician (formerly the advanced emergency medical technician-intermediate), and the Paramedic (formerly the emergency medical technician-Paramedic).

The emergency medical responder (EMR) is an EMS provider who is expected to render lifesaving care with minimal equipment. This person may be the lone provider on scene for an extended period of time. For example, a member of the emergency response team at a plant or a security officer at a shopping mall, would be an emergency medical responder.

The emergency medical technician (EMT)-Basic is part of a team that responds to the emergency scene, typically aboard an ambulance, and is trained to provide initial care on scene as well as medical care to the patient while in transit to the hospital.

The advanced emergency medical technician (AEMT) is an EMT with additional skills. These additional skills are skills or medications that have been shown to positively impact patient survival (i.e., evidence-based practices). These skills include the administration of a limited number of drugs as well as, among other things, supraglottic airway devices.

The highest level of EMS provider is the Paramedic. The Paramedic’s medical education includes advanced assessment and diagnosis of syndromes and disorders and the treatment thereof. In many states a Paramedic can obtain an associate’s degree or higher.

Each level of EMS provider has knowledge and skills that are clearly delineated. If an EMS provider was to perform a procedure that was not within one’s scope of practice then that individual could be accused of practicing medicine without a license.

Education Standards

In the past, the scope of practice for many EMS providers was defined by the National Standard Curriculum (NSC) for EMS. A seminal document, created with the assistance of the NHTSA in the 1970s, the NSC quickly became the only available source of information about the domain of prehospital emergency care (i.e., the scope of practice).31,32

With a definition of both the core content of EMS and the scope of practice of EMS establishing the domain of EMS, the National Association of EMS Educators (NAEMSE) set out to replace the NSC with the broader National EMS Education Standards. These National EMS Education Standards serve as the basis for EMS instruction and provide direction for EMS educators regarding both the core content and the scope of practice.

Accreditation

National EMS Education Program Accreditation, like other educational program accreditations, assures students who enter an EMS education program that the education they are about to receive meets national standards. Perhaps more importantly, accreditation helps assure the public, who depends on the graduates of those educational programs, that the graduates will be competent providers.

Presently the Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs (CAAHEP) accredits Paramedic education programs. CAAHEP grants accreditation after receiving a favorable report from the Committee on Accreditation of Educational Programs for EMS Professions (CoAEMSP). CoAEMSP site visitors visit the program and review the facilities, faculty, and courses of a Paramedic program to determine if they meet the national accreditation standards and then issue their report either recommending for or against accreditation. For most healthcare professions, graduation from an accredited school or program is a minimum requirement for entry to certification examinations. Eventually this will become the standard for Paramedic education as well.

Licensure and Certification

All states, as a matter of state rights, license individuals for practice in that state. Licensure permits an individual to practice a trade or a profession. Generally that license is issued after demonstration of satisfactory completion of a course of education, usually called a certification. By definition, a license precludes other non-licensed individuals from practicing in the profession or trade. If a non-licensed person was to practice, then that person could be accused of "practicing without a license," which might involve criminal and/or civil penalties.

In some cases the state not only licenses but also certifies those individuals, through written and practical testing, before they are licensed. This has been cause for some confusion about the difference between licensure and certification. Simply stated, any time a state gives an individual exclusive rights to perform a function or profession it is a license. The use of the term "certification" in this regard is a semantic difference. The National Registry of EMT has a well written legal opinion on the matter on its website.33, 34 In a growing number of states the certification of the

National Registry of Emergency Medical Technicians (NREMT) is accepted as proof positive that the individual being licensed is minimally competent to provide that level of care. Presently, the majority of states accept National Registry certification for licensure.

STREET SMART

The original designation EMT-A (the A was for ambulance) was changed to EMT-B (B for basic) to emphasize that EMTs operate in many varied environments other than the ambulance. Currently, the letter B has been eliminated altogether.

Mission of the EMS System

The fundamental mission of EMS has been to respond to a medical emergency, provide on-scene care, and transport patients to the closest appropriate medical facility. This mission is exemplified in the star of life, the symbol of EMS as represented by the six points; detection, reporting, response, on-scene care, care in transit, and transfer to definitive care.

To be effective, the EMS system must provide a coordinated response of health and safety resources in a timely manner and be successful in mitigating the effects of illness and injury. To attain this goal, EMS must have both horizontal linkage with other public safety agencies and vertical linkage with the rest of the healthcare system.

Through complementary relationships (i.e., horizontal linkage) with other emergency services, such as law enforcement and/or the fire service, EMS can realize efficiencies through rapid response and treatment.

Take, for example, a citizen who experiences a cardiac arrest. If a law enforcement officer (LEO) in a quick response system (QRS) were to arrive on-scene within minutes of the cardiac arrest, the officer could apply an automated external defibrillator (AED). Following the instructions of the AED, and the lessons learned during CPR training, lifesaving care could be initiated. (LEO is used to categorize that large group of professionals that are involved in law enforcement, including but not limited to constables, Sheriff’s deputies, police officers, state troopers, border patrol officers, agents and investigators from the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Drug Enforcement Agency, and so on.) Immediately afterward a basic life support (BLS) engine company from the fire service would arrive to support the LEO effort and provide additional skills and equipment, such as suction and oxygen. An advanced life support (ALS) ambulance would then arrive. The Paramedic would assume care of the patient, provide additional skills and equipment (such as intubation and ventilation), and transport the patient to the emergency department for stabilization. Once stabilized in the emergency department, the patient would be transferred to a coronary care unit (CCU) for further treatment and evaluation by a team of cardiologists. The patient’s entry into this critical care pathway is an example of horizontal linkage between EMS and the rest of the healthcare team.

This ideal system illustrates one example of the effectiveness that can be realized from an integrated approach to emergency response by all public safety agencies.

Legislation and Regulation

EMS at its core is a public service. As such, the public has certain expectations of performance. To ensure that EMS is available, states have enacted legislation that provides for the existence of EMS and regulates its functions.36-38

In many states this enabling legislation describes the various levels of providers and, more importantly, links the practice of those providers with the state medical practice act and physician oversight. Furthermore, these statutes typically empower either the state health department or the state department of state with responsibility for EMS system oversight.

At a larger, macro level, local, state, and federal government have an interest in EMS. EMS responds to and mitigates the consequences of a disaster as part of the larger government response. For that purpose, government often funds EMS disaster preparedness through grants and other mechanisms.

Public Access

When a citizen is suddenly confronted with a potentially life-threatening emergency, the person turns to EMS for help. To get that help, the citizen can use a variety of telecommunications devices but by far the most common means is to call on a telephone.

Previously the citizen had to memorize a seven-digit number for that jurisdiction. This often led to confusion and mistakes, some that were fatal. The obvious answer was to have a universal number for emergencies. Britain has had a universal number, 9-9-9, since 1937. However, the United States did not see a universal number, 9-1-1, until 1967.39-42 When that famous 9-1-1 call was made from Haleyville, Alabama, in 1967, the era of modern telecommunications was ushered in.

Early 9-1-1 service provided the public immediate access to the local public safety access point (PSAP), as well as automatic number identification (ANI), so that a "call-back" could be performed if necessary. Since that time, basic 9-1-1 has been improved. Enhanced 9-1-1 is now in use. Not only does it provide rapid access to emergency services, but computer-assisted dispatch (CAD) technology identifies the caller’s location as well.

With the growing number of mobile cellular telephones which cannot utilize the 9-1-1 technology, the early advantages of 9-1-1 location identification may have been lost. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is now working with the telecommunications industry and has undertaken a special wireless project that permits identification of a cellular telephone’s location within 125 meters. Telecommunications professionals, represented by the National Emergency Number Association, have been working to improve the public’s access to EMS.

Communication Systems

A typical EMS communication starts at the public safety access point (PSAP) when the professional telecommunicator, or dispatcher, answers the call and starts the emergency medical dispatch process. It ends when the Paramedic presents the patient over the radio to the medical control physician.

An overview of emergency communications underscores its importance. The emergency communications centers alert the public of impending natural disasters or terrorist attacks. From the simple color-coded terrorist alert used in the Homeland Security Advisory System to the Emergency Alert System (EAS) that predates the Homeland Security Advisory System, emergency communications professionals have been alerting the public to potential danger for years. Keeping up the tradition of watchfulness over our communities, telecommu-nicators can now alert drivers of a child abduction, via Amber alert, or dangerous persons with a special "be on the lookout (BOLO)" alerts via public signs and television announcements using the Emergency Notification System (ENS).

As technology improves, emergency communications takes advantage of these advances and incorporates them into the emergency communications system.

Architecture of EMS Systems

The wide variety of EMS system configurations speaks to the ingenuity of EMS officials and system administrators whose planning reflects the community’s capability to provide EMS.

Contemporary EMS depends on a number of configurations of emergency responders—some fire-based, some municipal, some volunteer, some proprietary, and some a combination of these—to ensure EMS is provided to the community.

System Configurations

The predominant means of delivering EMS in the United States is via fire-based EMS.43,44 The combination of trained personnel, lifesaving equipment, emergency vehicles, and strategically located stations make the fire service an ideal platform for the delivery of EMS.

The fire service has a long tradition of rescue and first aid. During World War II, in a time before self-contained breathing apparatus, many early fire services carried heavy E&J or Emerson Resuscitators for use in reviving firefighters and fire victims overcome by smoke and fumes. Eventually, the fire service started getting requests for "resuscitator" runs. Despite the availability of this equipment, medical calls remained infrequent until a few visionary physicians saw the potential of fire-based EMS.

Leaders in fire-based EMS—such as Dr. "Deke" Farrington of Chicago, Dr. Nagal of Miami, and Dr. Cobb of Seattle—saw the advantages in fire-based EMS and encouraged the fire service to get involved in EMS. Today, many major cities operate fire-based EMS services. For example, the Fire Department of New York (FDNY) operates the largest fire-based EMS service in the United States and had 1.2 million ambulance "jobs" or trips in 2007.

The International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC) and the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) has supported the development of fire-based EMS and has made EMS a major priority for the Fire Service (Figure 2-9).

Hospital-based EMS is another common EMS system design. When the large urban hospitals—such as the Commercial Hospital in Cincinnati or Bellevue in New York City—were started it became clear that these hospitals needed ambulance service to bring invalid patients to the hospital. In some cases proprietors of local livery stables dedicated a specially outfitted carriage for the hospital to provide special transportation. That tradition continues today in many large cities. New York City, for example, still has a large number of ambulances that respond from the "voluntary" hospitals.

In still other cases, groups of physicians established ambulance services, such as the Physicians and Surgeons Ambulance Service (P&S) of Columbia University.

Commercial ambulance services, or for-profit EMS, have long provided interfacility medical transportation as well as emergency medical services to patients. Many of these commercial ambulance services originated from the funeral homes that previously provided the service.

Today, commercial ambulance services provide EMS to vast areas. Some companies (e.g., Rural-Metro and American Medical Response) are so large that the company’s stock is sold in the market on the stock exchange.

Following the example of the Roanoke Volunteer Rescue Squad in 1920, rescue squads sprang up across America. These community-based EMS squads were independent of local fire departments and largely staffed with volunteers. Pressured by a lack of volunteers today, many of these community-based ambulances have turned to paid crews. However, the fact that these community-based ambulance services remain not-for-profit differentiates them from commercial ambulance services.

Some citizens believe that the government should provide EMS as part of its responsibilities for public safety. In those communities, a municipal EMS service was established as the third of three public safety departments (the other two public safety services being law enforcement and the fire service). In some cases small cities and villages would cross-train police officers as Paramedics to provide service and efficiency.

The military is decidedly the largest provider of emergency medical care (i.e., military emergency medicine) and has been providing EMS for a longer period of time than any other EMS system. The healthcare specialist and corpsmen of today’s military care for some 1.37 million active service men and women alone.

Figure 2-9 A fire service-based ambulance stands ready for an EMS call.

Modern EMS in the armed forces can be traced back to surgeon Jonathan Letterman’s efforts to establish a system of ambulances in 1864. In many respects the lessons that the military has learned while providing emergency medical care on the battlefield have been translated to emergency medical care in the civilian sector.