Inventors Hall of Fame. In 1987 Philip Sperber, a patent lawyer and an alumnus of the New Jersey Institute of Technology, began a campaign to acknowledge top inventors who improved the state’s standard of living. Two years later, a panel of industrial leaders and academics inducted Thomas Edison, Albert Einstein, and nine others. More than two hundred past and present inventors have been honored since then in exhibits at NJIT’s Guttenberg Hall in Newark and on a Web site hosted by the school. Inventions cited by the Hall of Fame range from television to ice cream cones and golf tees.

Irish. The arrival of immigrants from Ireland has been a feature of New Jersey history from earliest times. Insignificant in the seventeenth century, stronger in the eighteenth, exceptional in the nineteenth, and undimmed in the twentieth, the Irish presence has shaped the politics and culture of the colony and the state. In turn, the Irish were themselves shaped by New Jersey, some embracing it as a freer place than the country they left behind, others taking longer to warm to it. The relationship between host and settler, never easy, was fraught with tension for many years.

Seventeenth-century settlement was patchy and in some ways only marginally Irish. Quakers under the leadership of Robert Lane of Dublin established themselves in West Jersey (now Camden County) in 1681. Irish mainly in the sense of prior residence in Ireland, they most likely traced their real roots to England. Other settlements also originated in a desire for religious freedom: a group of Baptists came from Tipperary to live in Cohansey, Salem County, in 1683. Later they were joined by Presbyterians, probably from Ulster.

Individuals as well as communities made their way to East and West Jersey, eager for the enrichment that early colonial America seemed to promise. Dennis Lynch acquired 300 acres in Cape May from the West Jersey Company in 1696; John White of Carlow acquired 2,000 acres in Gloucester County in 1685. An occasional Jacobite may also be noticed in late seventeenth-century deeds. William Golden, an officer in the defeated army of King James at the Battle of the Boyne, acquired more than 1,000 acres at Egg Harbor in Cape May in 1691.

Eighteenth-century migration, mainly but not exclusively of Scots-Irish Presbyterians, was altogether more impressive. Drawn to New Jersey for a variety of reasons—religious tolerance, economic freedom, ample land— they settled in places that still bear their names: Hackettstown in Morris County, founded by Samuel Hackett of Tyrone in the 1720s; and Flemington in Hunterdon County, founded by Thomas Fleming, also of Tyrone, in 1746. They were a rough-and-ready bunch. In 1730 James Logan, provincial secretary of Pennsylvania, hoping that his fellow Ulster natives who had settled in the Quaker colony would move elsewhere, complained that they were "troublesome settlers to the government and hard neighbors to the Indians.” Many did leave Pennsylvania, crossing into central New Jersey to settle along the Millstone, Raritan, and Passaic rivers. Most fell into the category of "middling folk”: at the lower end of the scale, they were indentured servants, weavers, small farmers, and teachers; slightly higher up, preachers, lawyers, and merchants.

A scattering of Irish Catholics also lived in the colony in the eighteenth century. From 1765 to 1787 a German missionary, Father Ferdinand Farmer, tended to a small flock— perhaps a hundred or so—in the far-flung villages and homesteads of northwestern New Jersey. Most of these settlers were ironworkers employed by the Ringwood Company thirty-six miles north of Newark. Estimates vary as to the number of Catholics in New Jersey at the end of the eighteenth century, ranging between 200 and 900.

The Scots-Irish contribution to the Revolution was notable. Patriot leader William Paterson was born in County Antrim. John Neilson, member of the Continental Congress, was the son of Belfast parents. Irishmen also featured prominently in the Revolutionary army, so much so that in March 1780 Washington, fearing that their restlessness might lead to mutiny, organized a Saint Patrick’s Day ball at Morristown. It was, even Tories conceded, a triumph.

Nothing in the eighteenth century prepared New Jersey—or the rest of the United States—for the scale of Irish migration in the century that followed. Even before the Great Famine (i845-i85i)—the result of devastating and continued failure of the potato crop in Ireland—migration was on the rise. Newark’s first Catholic parish was created as early as i826 to cope with the influx. In Paterson the Friends of Ireland—part social club, part ginger group supporting Andrew Jackson for the presidency—numbered eighty-five in i828. Irish labor was largely responsible for the building of the Morris Canal in the i820s, the Delaware and Raritan Canal in the i830s, and the Morris and Essex Railroad in the 1840s and 1850s. Precisely as industrialization gathered speed in New Jersey, a ready supply of Irish brawn—and sometimes brain—arrived to help it along. "New Jersey is rapidly becoming a great manufacturing state … a place of resort for emigrants for seeking work," noticed Bishop James Roosevelt Bayley in 1853. "The emigration is again flowing in upon us," he wrote to the rector of All Hallows College in Dublin in i860. "I was never more in want of good zealous priests."

The famine Irish huddled together. A rural, Catholic people suddenly transplanted to an urban, industrial state, they congregated for comfort in various little Irelands: the Iron-bound in Newark, the Fourth Ward in Trenton ("Irishtown" in the 1850s), the "Dublin" sections of Paterson and Morristown, and the Horseshoe in Jersey City. Solace was sought in the usual places—the parish, the pub, the political meeting. Eventually the sheer scale of the migration transformed New Jersey^ social geography. In 1855, there were 40,000 Catholics in the state, served by 35 priests, 17 of them from Ireland. By 1872, there were 170,000 Catholics, 113 churches, 62 priests, and a seminary, Seton Hall College. In i880 there were 184 priests and 142 churches. Many of the clergymen were Irish-born or the children of Irish immigrants.

By the end of the nineteenth century an Irish establishment had begun to emerge. Ecclesiastically, they were the most dominant group in the state—a fact occasionally resented by Germans and Italians, the former in particular. Politically, they were a force to be reckoned with, especially in Newark, Jersey City, and Trenton. Socially, they seemed almost respectable. As new ethnicities swamped the state, especially immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, the Irish looked not so threatening as before.

The twentieth century magnified these trends. Irish political dominance, for good or ill, came to be associated with the urban machines of larger-than-life figures like "Big Jim” Smith of Newark, Thomas McCran of Paterson, and (boss of bosses) Frank Hague of Jersey City. A parallel development was Irish participation in unionism and labor politics. The Paterson silk strike of 1913, the Gloucester City trolley strike of 1919, and the Camden shipyard strike of 1934 all owed something to Irish industrial activism.

The price of this success was diminished ethnic identity. "Irishness" lost much of its social salience in an era of suburbs. It was a reason for Saint Patricks Day celebrations, or perhaps the motivation for a trip to Europe— little more. When Irish Americans achieved the highest office in the state with the gubernatorial victories of Richard Hughes in i96i and William Cahill in i970, a once marginal group had come into its own. For all that, their Irishness, by now attenuated and sentimental, seemed hardly very Irish any more.

Iron industry. The mining and manufacturing of iron was important to New Jersey for over two centuries. Large bodies of quality ore and numerous manufacturing facilities, in combination with New Jersey^ strategic location, established the state’s importance as an iron producer to the nation. New Jersey iron was integral to agriculture, construction, transportation, and weaponry from colonial times to the beginning of the twentieth century.

Iron ores are common throughout New Jersey, from magnetite and hematite in the north to the bog iron more common in the south. While New Jersey Indians used powdered ore for pigments, they had no knowledge of refining the metal. Northern iron resources may have been explored by European settlers as early as i649, but the first known ironworks in the state was James Grover’s circa i670 Tinton Furnace, in today’s Monmouth County—one of the first furnaces in the country. In the north, the i685 Troy forge was the first recorded refinery. It appears that the first serious exploitation of northern New Jersey iron deposits began at this time.

Ore was first mined informally under "forge rights,” whereby ore was extracted by private forgemen, mining for their own personal use and not for resale, from properties such as farms that were not operated as formal mines. The property owner would make a small additional income, and the forgeman would get the ore cheaper than buying it from a mine. The southern iron works relied on scattered but sometimes extensive bog ore deposits. The first was discovered near Shrewsbury in Monmouth County. The two largest, covering sixty square miles each, were along the Mullica and Wading rivers. The first established mine in the north was the circa i7i5 Dickerson Mine in Morris County. Subsequently, ore explorations resulted in the opening of numerous additional mines. The largest ones produced over 50,000 tons per annum at their peak, with ore quality frequently comparable to the best in the world.

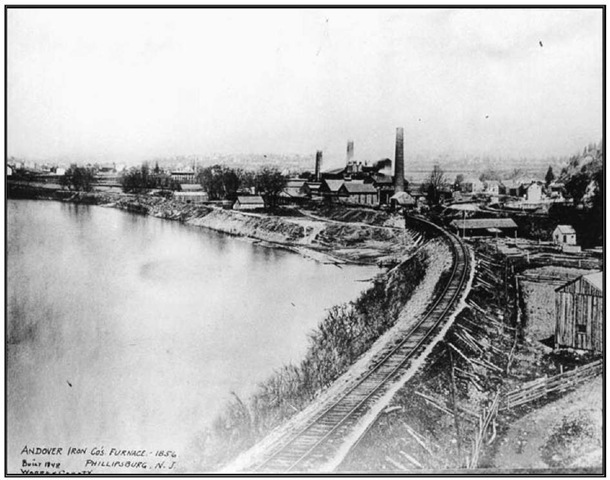

Andover Iron Company Furnace, Phillipsburg, 1856.

Ironworks began with bloomery forges for wrought iron, and larger furnaces for cast iron—both charcoal fueled. There were perhaps two hundred of these operations in the state. The introduction of hot-blast furnaces and anthracite fuel in the i830s made many manufactories obsolete. They were also very dependent on ease of transportation, market fluctuations, and other economic conditions. Periodic financial depressions put many out of business. Most of the surviving enterprises closed with the i890s opening of the Lake Superior ore beds, which could be quickly, easily, and more safely strip mined, and which were closer to ship transport. Much of the refining process for New Jersey ores was already in the hands of Pennsylvania iron companies that had bought out owners of the more productive Garden State mines.

A few iron mines and furnaces attempted to take advantage of bullish iron markets into the twentieth century. However, these markets rarely lasted, and the industry eventually died. The largest of the surviving mines, at Mount Hope and Hibernia, saw their last major production in the 1950s. Despite later attempts to revitalize their operations, only Mount Hope remains in operation—now for quarrying mineral products other than iron.

Irvington. 2.8-square-mile township in Essex County. Initially used for pasture and wood lots by Newark landholders, as the town population increased farms were established, homes built, and a separate town took shape (traditionally 1692). Eventually, the Camp family owned one-third of current Irvington, and starting about 1800 the settlement was called Camptown. The popularity of Stephen Foster’s Camptown Races prompted residents to rename their village in 1852 to honor Washington Irving, and the federal government changed the post office name of the unincorporated village of Camptown to Irvington on November 22, 1855. Irvington remained a section of Clinton Township until becoming independent in 1874.

Fertile land made produce farming the primary industry in Irvington until competition from southern crops destroyed the market. Renowned strawberry and greenhouse flower industries continued into the twentieth century, and then were replaced by industry and workers spreading out from Newark. Olympic Park, a picnic ground frequented by German Americans, developed into a major amusement park after 1901 with numerous attractions, including the world’s largest swimming pool. Today Irvington is home to a number of light industries as well as being a dense residential community plagued by urban decay. In 2000, the population of 60,695 was 82 percent black and 9 percent white. The median household income in 2000 was $36,575. For complete census figures, see chart, 133.

Iselin. 2.8-square-mile section of Woodbridge Township in Middlesex County. First occupied by European farmers in the seventeenth century, a settlement developed at the T intersection of today’s Green Street and Chain O’ Hills Road. The town received its charter on June 1, 1669, under the name "Perry town,” perhaps named for the tavern keeper of the inn at the intersection. On April 16, 1859, a religious group called the Union Society filed for a name change to Unionville. This name lasted until the 1870s, when the town was renamed Iselin for Adrian George Iselin, a successful New York stockbroker and philanthropist. There are several conjectures as to why the town was renamed in Iselin’s honor. According to one version, it was because Iselin was instrumental in establishing an exclusive finishing school for girls in the town, in another, because he subsidized the erection of a new train station (the railroad company subsequently changing the station name to Iselin). Today, the station in Iselin, now called Metro Park, is a park-and-ride rail station, dedicated in 1971, that services the Northeast Corridor and has been responsible for the growth of the office and industrial complex also known as Metro Park. This, in part, has been responsible for the 12 percent increase of the East Asian Indian community in the area since 1990.

Islam. Islam, the submission of the individual will to the will of Allah (God), is based on the seventh-century teachings of its Arab founder, the Prophet Muhammad ibn ‘Abdullah, as recorded in the Holy Qur’an. Muslims (adherents to Islam) believe that Islam represents Allah’s last revelation to humankind, following in succession the prophets of Judaism and Christianity. The five pillars of Islam require that Muslims confess their faith in Allah, pray five times daily, fast during the month of Ramadan, give to charity, and make a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in their lifetimes.

In the United States in 2000, although population estimates of religious affiliation are imprecise, there were between 4 and 8 million Muslims. Reflecting the ethnic, cultural, and political diversity found across the United States and the world, New Jersey Muslims have been actively building Islamic communities since the 1910s. One of the earliest was the Black Nationalist Moorish Science Temple of America, founded in Newark in 1913. In 1920 a missionary group from India, the Ahmadiyya Movement in Islam, began converting European and West Indian immigrants in Gloucester. Both of these communities continue today, although they, like the Shi’i and the Nation of Islam, are small in comparison with the majority orthodox communities of Sunni Muslims.

With significant populations of African Americans, and with an increasing number of Middle Eastern and African immigrants since the 1960s, New Jersey cities such as East Orange, Jersey City, Newark, New Brunswick, Paterson, and Trenton, as well as their surrounding suburbs, are major centers for Sunni Islamic worship, community services, and schools. In 2000 an estimated 300,000 Muslims lived in New Jersey.

Island Heights. 0.6-square-mile borough located near Toms River in Ocean County. Dotted with Victorian-style homes, Island Heights overlooks the Toms River.

The first inhabitants were the Lenape Indians, who came to fish. In 1698, the Dillion Family purchased the "island” (it is really a part of the mainland), but they were banished at the end of the eighteenth century for being Loyalists. In the early 1800s, shipping became lucrative. When land erosion silted up the waterway, it made navigation difficult and shipping declined. In the late nineteenth century, a group of Methodists purchased the land and formed the Island Heights Association. The intention was to promote a Christian camp meeting ground. The prohibition of the sale and consumption of alcohol remains in effect today. In the early twentieth century, John Wanamaker, a Philadelphia retail merchant, purchased thirteen acres to provide a two-week summer camp to his employees under the age of eighteen. The camp regime consisted of morning military drills and afternoon leisure activities. The town of Island Heights has taken ownership of the abandoned campsite; future plans involve a cultural center. In spite of the population increase and passage of time, small family-owned businesses still continue to flourish in this quaint shore town.

The population in 2000 of 1,751 was 98 percent white and the median household income was $61,125. For complete census figures, see chart, 133.

Israel Crane House. The home of the Crane family in Montclair was constructed in 1796 by Essex County entrepreneur Israel "King” Crane. Crane established a prosperous general store in Montclair and built a toll road from Newark to Caldwell. The original Federal-style house was later remodeled in the Greek Revival style to include a raised, flat roofline, a columned front porch, and distinctive open-work wrought iron grills. The Crane House was moved from Glen Ridge Avenue to its present Orange Road location in 1965 by the Montclair Historical Society, which uses the house as its headquarters.

Italians. Italians are the largest ethnic group in New Jersey today, constituting nearly 20 percent of the state’s population. Yet they hardly figure at all in the early history of New Jersey, even though one of the first Italian New Jerseyans, Giovanni Battista Sartori, established the first Catholic church in New Jersey and the first spaghetti factory in the United States, both in Trenton around 1800.

In the census of 1860 only 105 New Jerseyans were recorded as born in Italy. That number would rise dramatically in the last decades of the nineteenth century. In i886 there were 3,000 Italians in Newark alone, with new immigrants arriving daily in large numbers. The state’s population of Italian immigrants reached a peak in 1930, when 190,858 New Jerseyans listed Italy as their place of birth. Although the number of New Jerseyans actually born in Italy has since declined to 58,395 (according to the 2000 census), the number of persons claiming Italian ancestry continues to grow impressively. Thus, in the decade between i980 and i990, the total population of New Jersey’s Italian Americans rose from 1,289,100 to 1,446,420.

Many of New Jersey’s first Italian immigrants in the 1870s settled in southern New Jersey, where they worked as agricultural laborers in towns like Vineland and Hammonton. From the i880s onward, many Italians from the Philadelphia area worked as migrant laborers during the summer in the fields of south Jersey. But by the 1880s, with the start of the great wave of Italian immigration, most of New Jersey’s Italian newcomers found work in the urban construction trades-even though most of them had had experience only in agricultural work in rural areas of southern Italy. The life they found here was memorably described in Pietro di Donato’s novel Christ in Concrete (1939), about the struggle of an Italian family to survive in Newark. Other cities that received large numbers of immigrants were Trenton, Jersey City, Paterson, Hoboken, Union, and Camden.

In New Jersey, as elsewhere, Italians from the same regions or towns tended to settle together, in what have been called "urban villages.” Thus Newark’s First Ward had a heavy concentration of immigrants from the province of Avellino, in the Neapolitan hinterland; Trenton became home to many Italians from the province of Potenza; Hoboken received many Italians from Malfetta in Puglia; and a large group from Vasto, in Abruzzo, settled in Union City. Some Italians in New Jersey’s cities were active in socialist and anarchist causes and also in the nascent labor movement. Paterson, in particular, was a hotbed of anarchism. It was in Paterson that Gaetano Bresci, who would assassinate Italy’s King Umberto I in i900, learned his anarchist doctrine and also acquired the fatal revolver.

Italians in New Jersey have had a historically interesting relationship with the Roman Catholic Church. In the i890s and early i900s Presbyterian, Baptist, and Methodist missionaries were able to find significant numbers of converts among the Italian immigrants. The Catholic Church responded by establishing "Italian” parishes with Italian-speaking priests. At first these were not always successful. In a candid letter of 1892 an Irish American priest who had learned Italian in Genoa and been assigned to an Italian parish in Newark requested transfer to an "English” parish, because "I have a sort of dread of the Italians … I have spent days plucking up courage to call on families that were being perverted from the faith, [but] time and again I… have walked past their houses for the want of courage to enter.” In 1896 a parishioner in Jersey City (Gersori Citi) wrote to Bishop Winand M. Wigger, criticizing an Italian priest who had abandoned his Italian church, leaving "many weak and under the slavery of the Americans.” Yet, the creation of specifically Italian parishes and also the extensive work of the sisters of the Filippini Order, who arrived first in Trenton in 1910, encouraged the overwhelming majority of Italians to remain Catholic. In more recent times, parishes such as Saint Lucy’s and Saint Rocco’s in Newark continue to serve as religious and cultural focuses for many of the state’s Italian Americans.

During the fascist period in Italy, the government of Mussolini received substantial support from Italians in New Jersey. Fascist "circles”were established in Camden, Garfield, Hackensack, Hoboken, Jersey City, Montclair, Nutley, Orange, Trenton, West Hoboken, and West New York. Contacts between the fascist regime and New Jersey Italians were even encouraged by the Roman Catholic Church in the 1920s and 1930s, after the Italian government’s Concordat with the Vatican. In 1929 Bishop Thomas Walsh led a delegation of Boy Scouts of the Fascisti League of North America on a visit to Rome and Mussolini. Ten thousand people attended a fascist rally in Morristown in 1936, held on the grounds of the Filippini Sisters at Villa Walsh. In those same years, however, Italians active in labor unions and the socialist movement spoke out against Mussolini and fascism. An antifascist newspaper, La scopa (The Broom), was published in Paterson by Francesco Pitea. And the antifascist historian Gaetano Salvemini made a public address in Hoboken. After Pearl Harbor and Mussolini’s declaration of war on the United States, support for fascism quickly disappeared. More than 68,000 New Jersey Italian Americans served in the U.S. armed forces in World War II. Gay Talese’s remarkable family history, Unto the Sons, which is centered on his youth in Ocean City, describes the awkward but substantial patriotism of Italian Americans during the war.

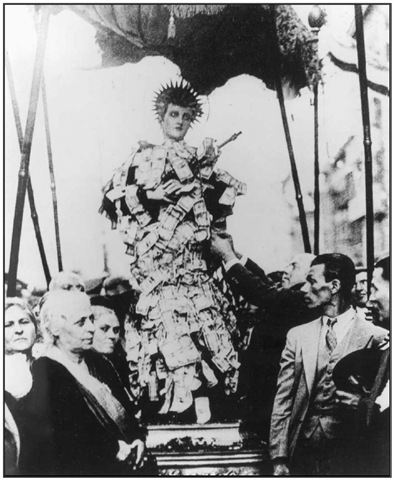

Feast of Saint Gerard, Newark, 1935.

The postwar years brought prosperity to many Italian Americans, who in large numbers moved out of New Jersey’s major cities to the suburbs. Those years, too, saw significant numbers of Italians enter state and national politics, a generational cohort that was led by U.S. Representative Peter Rodino. After decades of successful assimilation into an American culture that they also in large part helped to create (in music, note Frank Sinatra and Bruce Springsteen—Italian on his mother’s side), New Jersey’s Italians are increasingly asserting their own cultural identity and proudly exploring their rich history.

![tmp5-29_thumb[1] tmp5-29_thumb[1]](http://what-when-how.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/tmp529_thumb1_thumb.jpg)