Ives, Charles Edward (b. Oct. 20,1874; d. May 19,1954). Composer. Charles Ives served from 1898 to 1899 as organist of Bloomfield’s Presbyterian "Church on the Green.” His father was an unconventional town bandmaster in Danbury, Connecticut. Ives similarly remained a nonconformist, building on a solid musical education at Yale with explorations into new forms and rhythms. A successful insurance business allowed him to support his family and remain unfettered by the musical establishment. After business hours,he composed three symphonies and dozens of songs and chamber and piano pieces. He lived to see his work performed by leading artists and to receive a Pulitzer Prize.

Jackson. At 100.4 square miles, the largest township in Ocean County. Incorporated in March 1844, Jackson was settled by the English in 1665 after New York governor Richard Nicoll ousted Peter Stuyvesant, ending Dutch sovereignty in colonial New Jersey. Nicoll gave the Monmouth Patent to twelve Englishmen from Long Island, granting them the eastern half of the township in what was then Monmouth County. The township, named in honor of former president Andrew Jackson, included the lower portions of Freehold and Upper Freehold townships and the northern end of Dover Township. In 1845, part of the original township was set aside to create Plumstead Township, and in 1850, the township became part of Ocean County. In 1928, Jackson Township acquired a portion of the western section of Howell Township.

Jackson’s colonial industries included agriculture, forestry, charcoal manufacturing, and cranberry production. After World War I, poultry farming dominated. Cassville is noted for its Russsian settlement; onion-domed Saint Vladimir’s Church is open for tours. Today, Jackson is a suburban township that includes retirement communities as well as the Great Adventure entertainment theme park. The population of Jackson according to the 2000 census was 42,816, and was 91 percent white. The median household income in 2000 was $65,218. For complete census figures, see chart, 133.

Jacobs, Nathan L. (b. Feb. 28,1905; d. Jan. 25, 1989). Lawyer, jurist, and chief justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court. Born in Russia, Nathan L. Jacobs immigrated to America at an early age and attended public schools in Bayonne. He graduated from the University of Pennsylvania in 1925 and earned an LL.B. and an S.J.D. from Harvard Law School in 1928.

After admission to the New Jersey bar in 1928, he practiced law in Newark with Arthur Vanderbilt, future chief justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court, and later held several governmental positions, including state attorney in the Office of Price Administration during World War II. He married Bernidine Rosenbaum and they had two daughters.

In 1947 Jacobs served as a delegate to the state constitutional convention and was instrumental in revising the antiquated court system. In 1948 Gov. Alfred Driscoll appointed him to the superior court and in 1952 to the supreme court, where he served until mandatory retirement in 1975.

As a judge, Jacobs was noted for keen intellect and prolific writing. Never hesitant to initiate reform, he declared, "When a doctrine of law is unfair, it must be changed into a concept that serves today’s society.” His decisions led to the establishment of the right of tenants to sue landlords, teachers to obtain reasons for dismissal, and prisoners to receive justification for parole denial.

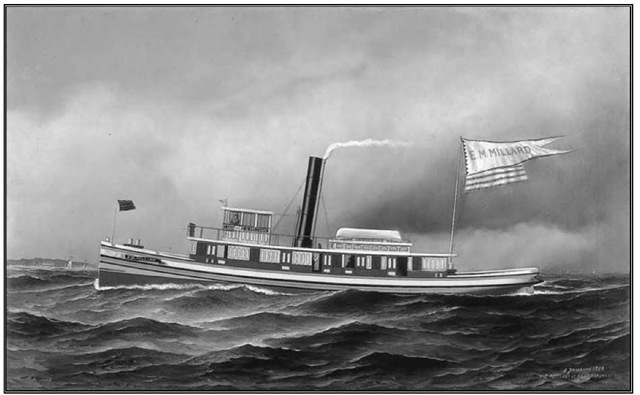

Antonio Jacobsen, E. M. Millard, 1889. Oil on canvas, 22 x 36 in.

Jacobsen, Antonio Nicolo Gas paro (b. Nov. 2, 1850; d. 1921). Painter. Born in Copenhagen, Denmark, Antonio Jacobsen became known as the "Audubon of Steam Vessels.” More a musician by profession than an artist, Jacobsen became a student of realism at the Royal Academy in Copenhagen. In 1871 he immigrated to the United States to escape service in the Franco-Prussian War. He worked as a safe decorator for the Marvin Safe Company in New York City.

A few years later, Jacobsen began to paint portraits of the ships owned by the Old Dominion Steamship Line. In the years between 1876 to 1919 he painted more than 5,900 portraits. His images of the ships were often based on the plans and blueprints supplied by the builders of the ships. Sail and steam, commercial and naval, large and small, all manner of craft found representation in Jacobsen’s work. His clients—mostly ships’ officers, crewmen, and owners—demanded accuracy. And accuracy was what they received. So well, in fact, did he document this parade of ships, and New York’s importance as a port, that he deserves the dual titles of marine historian and marine artist.

Although he probably never visited Louisiana, Jacobsen received many painting commissions between 1876 and 1909 from shipping lines based there, including the Central American Steamship Company, the Morgan Line, and the New Orleans-Belize Royal Mail Company. These companies often asked Jacobsen to render the image of a particular ship for each port where the companies maintained an office. Consequently, it was relatively common for him to paint numerous portraits of the same ship, only in different settings.

In 1880, he moved to West Hoboken and set up a studio from which he painted a variety of marine and ship portraits. According to Who Was Who in American Art "in his later life, his daughter, Helen, helped paint the sky and water of his pictures. His son Carl even painted some of his own ship portraits.”

Most of his paintings are signed and his address was often included as well. This is thought to have been a method of advertisement. During all but his last few years, Jacobsen enjoyed a comfortable lifestyle, which reflected the financial success of his life’s work. He died in West Hoboken in 1921.

Jacobson, Joel R. (b. July 30,1918; d. Dec. 26,1989). Labor leader and public official. Joel Jacobson was born in Newark and graduated from New York University with a degree in journalism in 1941. He became involved in the labor movement as an organizer with the International Ladies Garment Workers’ Union. Following military service in World War II, he quickly rose to become a major figure in New Jersey’s industrial union movement. As an executive vice president of the New Jersey Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) and as president of the New Jersey Industrial Union Council, he played a central role in the rivalry between New Jersey’s young industrial unions and the older unions of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in the 1950s and 1960s. He also served as community relations director for Region 9 of the United Auto Workers from 1968 to 1974.

The 1970s saw Jacobson serve in a series of political appointments. After three years of service on the state’s Board of Public Utilities, he was appointed New Jersey’s first energy commissioner in 1977, a post from which he attacked major oil companies for price gouging. In 1981 Gov. Brendan Byrne’s appointment of Jacobson to the Casino Control Commission spurred a contentious senate confirmation hearing. His careful scrutiny of casino practices and outspoken criticisms contrasted strongly with the board’s traditional deference to the industry’s leaders.

In 1986 he was appointed by a federal judge to be trustee of Union City’s Teamsters Local 560 under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) statutes. The notoriously mob-dominated local was then controlled by confederates of gangster Anthony Provenzano. Jacobson’s efforts to purge the union of the mob while encouraging "democratic, militant trade unionism” among its members did not satisfy Judge Harold A. Ackerman, who replaced Jacobson a year later with Somerville lawyer Edwin Stier.

James, duke of York (b. Oct. 14, 1633; D. Sept. 16, 1701). Lord High Admiral of the British Navy, Lord Proprietor of New York, and later King James II (1685-1688). The second son of King Charles I, James, duke of York, and his older brother Charles spent much of their youth in exile in France and the Netherlands after their father’s regicide, trying to muster a force that would bring the monarchy back to power and the English Civil War to a close. In 1660, Charles II was restored to his father’s throne, giving James control of the royal navy, which he reorganized and used to encourage English trade and colonization. The duke helped to organize the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa (later the Royal African Company) and the Morocco Company, which strengthened the Crown’s monopolies in many areas of trans-Atlantic commerce, including the African slave trade.

As the country eased back into monarchal rule, James and his brother turned their attention across the Atlantic Ocean to England’s American colonies: Puritan New England was operating nearly autonomously of the mother country, and the Dutch had settled on land that England claimed, but had been unable to develop during their years of political turmoil. By allying himself with merchants, traders, and members of Parliament opposed to the economically powerful Dutch, James soon stood at the head of a powerful faction that recommended military action against the Dutch colonies in New Netherland. In September 1664, Col. Richard Nicholls, commanding a fleet of three English battleships, sailed into the Dutch port of New Amsterdam, where his men outnumbered Dutch troops by nearly two to one. The town surrendered immediately, and was soon renamed New York.

Earlier, in March 1664, Charles II had granted to his brother James a large swath of land encompassing what is now New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland, as well as Maine and other areas north of the original New England colonies. Within two months, James had transferred his rights over a portion of that territory to his friends Lord John Berkeley and Sir George Carteret. The land was "to be called by the name or names of New Caserea or New Jersey,” after Carteret’s Isle of Jersey home. Colonel Nicholls, who had already begun selling some of the New Jersey lands when he heard of the Berkeley-Carteret grant, protested to James that he was giving up the best part of his territory. He suggested that Berkeley and Carteret would not be able to make the best of the region’s potential, but the duke refused to rescind his gift.

James stayed out of the political and legal struggles in New Jersey. Only once did he step in: to support Sir George’s cousin Philip Carteret in his efforts to recapture his governorship, after one disgruntled New Jersey faction tried to establish Sir George’s son James as a more tractable governor.

James is best known for his brief but ignominious stay on England’s throne. Crowned in 1685 after his brother’s death, James was unpopular, both for his absolutist tendencies and his open Catholicism. In 1688, he was deposed by his daughter Mary and her husband, William of Orange, and was forced to spend the rest of his life in exile.

Jamesburg. 0.9-square-mile borough in southern Middlesex County. Jamesburg was first settled in the late 1600s by a Scotsman, William Davison, in proximity to the Man-alapan Brook. In 1832 the Camden and Amboy Railroad, which crossed the upper part of town, changed the future of Jamesburg, increasing travel and commerce and assuring it would not pass into oblivion as many early grist- and sawmill sites had. It was incorporated in 1887 when it split off from the township of Monroe. The borough was named for James Buckelew, landowner, pioneering farmer, and enterprising businessman. He also built his own school to which "all children were welcome.” The cornerstone read "James B” and the growing settlement soon became known as James B. or Jamesburg. In early days it was home to the world’s largest shirt factory (Downs, Gourlay, and Finch established 1871). Other industries were Kerrs’ Butterscotch Company and the railroad, which employed about three hundred people.

Today the borough is primarily residential with many fine shops lining its business district. The 2000 census showed the population of 6,025 to be 83 percent white, 9 percent black, and 10 percent Hispanic (Hispanics may be of any race). Median household income in 2000 was $59,461.

James J. Howard Marine Sciences Laboratory. Through the efforts of Dr. Lionel A. Walford, the Sandy Hook Marine Laboratory was established in i960 under the U.S. Department of Interior, Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. The laboratory was housed in the former Fort Hancock Army Hospital, which was designed by Stanford White in the i890s on Sandy Hook. Destroyed by fire in i985, the original laboratory was rebuilt in i987 near the old site and renamed the James J. Howard Marine Sciences Laboratory, after the U.S. representative for New Jersey’s 3d District who led the rebuilding effort. A new laboratory was constructed in 1989. The lab is part of the Northeast Fisheries Science Center, NOAA Fisheries, U.S. Department of Commerce. The mission of the research conducted at the lab is to characterize coastal marine habitats and understand habitat ecology with respect to management of fishery resources.

James Lawrence House. The James Lawrence House, located at 459 High Street, Burlington, is a two-and-one-half-story structure attached to the James Fenimore Cooper House. Hugh Hartshorne, a Burlington colonial official, had the house built around 1742. The architect is unknown. Major renovations altered the house in about 1782 and 1820, and twice in the 1940s.

The association of James Lawrence, the U.S. naval hero, with the house is minimal. Lawrence was born there and lived in the house with his father and siblings until the age of twelve. As commander of the USS Chesapeake, Lawrence was mortally wounded in a naval battle in 1813 and earned lasting fame with his final command, "Don’t give up the ship!”

Ownership of the house changed frequently over the years. William Marrs acquired the property in 1908 and four years later deeded it to his five sisters, Sophia, Margaret, Sara, Annie, and Jessie Marrs. In 1942 the three surviving sisters deeded the property to the state of New Jersey. The Burlington County Historical Society maintains and operates the Lawrence House for the state.

The interior of the house, which is open to the public, is furnished to a circa 1820 style. Contents include some Lawrence family furniture and wood from the Chesapeake. The gold medal commissioned by Congress to honor Lawrence for his heroism in sinking the HMS Peacock (1813) is displayed under glass. Photographs of ships named for Lawrence hang in various rooms.

James Wilson Marshall House. The boyhood home of James Wilson Marshall (1810-1885), the first person to discover gold in California, is located on Bridge Street, the main thoroughfare of Lambertville. The Federal-style brick house was built in 1816 by Marshall’s father, Philip, who operated his wheelwright shop on the same property. The Marshalls were among the earliest European settlers in the area, and their original homestead, Round Mountain Farm (still known as Marshall’s Corner), is located in Hopewell Township, Mercer County, approximately nine miles east of Lambertville. In 1834 Marshall’s father died, and the house and property were sold to pay debts. James traveled west, settled in California in 1845, and at Sutter’s Mill in January 1848 discovered the gold that made him famous.

In 1967 the Marshall House was deeded to the New Jersey Department of Conservation and Economic Development by its then owner, the Church of Saint John the Evangelist. Currently, the Lambertville Historical Society rents the house for use as its headquarters. The Marshall House is listed on the New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places.

Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum. The Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University was founded in 1966 as a small art gallery on the New Brunswick campus. The museum has been expanded five times since its inception. With approximately fifty thousand works of art, and with a total of 35,000 square feet of exhibition space, the Zimmerli Art Museum is now ranked, according to the Association of Art Museum Directors’ 2001 statistics survey, among the top 5 percent of university museums in the nation.

The museum’s extensive and varied permanent collections include concentrations in nineteenth-century French graphics, Russian and Soviet art, twentieth-century American art, and contemporary printmaking. With almost twenty thousand works of art from the Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union, along with the George Riabov Collection of Russian art, the museum houses the largest collection of Russian art outside Russia. The permanent collection also features a survey of Western art from the fifteenth century to the present, with an American art collection of painting and sculpture highlighting mid-twentieth-century surrealism and abstraction. Other significant collections include American Stained Glass, Rutgers University Collection of Illustrations for Children’s Literature, Women Artists, and Japonisme.

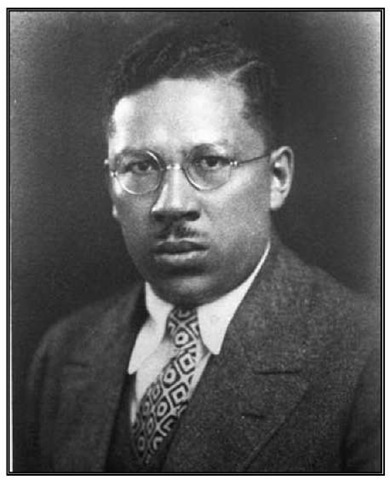

Janifer, Clarence Sumner (b. 1886; d. Nov. 14, 1950). Physician and public health official. A native of Newark, Clarence Sumner Janifer graduated from New York Homeopathic Medical College in 1915. He began practice in Newark in 1915, specializing in pediatrics. He successfully challenged the status quo by becoming the first African American member of the Medical Society of New Jersey (founded in 1766) in 1916. As a medical officer with an American infantry unit, Janifer was awarded the French Croix de Guerre for bravery during the First World War. He was employed for over forty years by the Newark Health Department, earned two master’s degrees in health, and was one of two African American physicians who integrated the staff of the Newark City Hospital in 1948.

Dr. Clarence S. Janifer, c. 1946.

Japanese. The first Japanese in New Jersey were students who came to New Brunswick in the 1860s to study at Rutgers College and Rutgers Grammar School (now Rutgers Preparatory School). At the end of the Tokugawa era and early Meiji period, local and central governments encouraged study abroad as part of Japan’s drive to acquire Western knowledge. Rutgers College had close ties with the Dutch Reformed Church, whose missionaries, such as Guido Verbeck, were active in Japan during the Meiji period. The missionaries’ influential role as educators encouraged many of their students to choose Rutgers as their study destination and led to a strong New Jersey-Japan educational exchange. After their studies, some of the first students gained social distinction in Japan; the best known of all was Matsukata Kojiro, who became an industrial entrepreneur and major art collector. Others less fortunate, such as Kusakabe Taro, died while attending Rutgers and were buried in the Willow Grove Cemetery in New Brunswick. The tradition of educational exchange is maintained today, involving the city of New Brunswick and Rutgers University and the cities of Fukui and Tsuruoka and Fukui University.

The second Japanese influx occurred between 1944 and 1946, when citizens of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast settled at Seabrook, forty-five miles south of Philadelphia, to work at the farm and food-processing plant owned by Charles F. Seabrook. These Japanese Americans had been subjected to a series of security measures that culminated in forced removal from their homes into internment camps. When the U.S. Army reversed its internment policy in 1944, the War Relocation Authority, the civilian agency created to care for the evacuees, relocated four generations of Japanese Americans, approximately twenty-five hundred people, to southern New Jersey. This group, the largest incoming ethnic group in the area at the time, arrived from camps in Arkansas, Arizona, and California. The community thrived until the late 1960s, then declined as the younger generation left the farm to seek educational and professional opportunities elsewhere. Today, only few people of Japanese ancestry remain in the Seabrook area.

The third significant influx of Japanese consists mainly of corporate business people and their families. In the last quarter of the twentieth century, they established temporary residence in Fort Lee and its vicinity during their overseas assignments in the New York area. The economic expansion of Japanese companies in the United States in the 1980s and early 1990s brought a record number of Japanese into Fort Lee, Cliffside Park, and Edgewater, where Japanese-oriented businesses, services, specialty stores, and restaurants thrive, making the area a Japanese enclave in the state. In addition to proximity to New York City and affordable real estate, the presence of a Japanese school in Fort Lee, operated according to Japanese Ministry of Education curricular standards, has been an important attraction for Japanese families with school-age children. In 2000, the total population of Japanese citizens in New Jersey was 26,556.

Jazz. Legend has it Sarah Vaughn was "discovered" at Harlem’s Apollo Theatre. But back in Newark, some folks tell another story. Vaughn grew up singing with the Mount Zion Church choir and when she was about seventeen, local concert promoter Carl Brinson gave the eager girl with extraordinary range her big shot. He hired her to sing at the old Picadilly, on Peshine Avenue, "the first modern nightspot in Newark to welcome blacks,” Brinson said. Brinson, known as "Tiny Prince,” said he knew Vaughn was going places, even when others—like his business partners— weren’t so sure. "Sarah, to them, sang off-key,” he said. Vaughn would soon after win the amateur night contest at the Apollo in 1942, and continue her rise to international fame, eventually earning the nickname "The Divine One.” There are other Jersey jazz angels: Count Basie grew up in Red Bank. And many a career was nurtured around the state and launched from places like Paterson and Trenton, once destinations for the jazz elite.

By the 1920s, Newark was a destination for blacks heading north during the Great Migration. Newark nightlife was brimming with vaudeville, theater, and music. On Thanksgiving of 1925, the empress of the blues, Bessie Smith, performed at the Orpheum Theater (now the offices of the Star-Ledger). In this time of Prohibition speakeasies were just about everywhere. And for many in the black community, an evening’s entertainment came in the form of a "house rent” party. For just a quarter admission, revelers enjoyed liquor and live jazz. Fats Waller and the Newark stride pianist Donald "The Lamb” Lambert played house rent parties and Ike Quebec, the legendary tenor saxophonist, launched his career at one. With the end of Prohibition, Newark’s nightlife blossomed even more. In 1938, according to Barbara Kukla, it had more saloons per capita than any other American city. Music was everywhere, spilling from storefront churches, neighborhood barbecues, and street corners. "Newark used to be the swingingest town,” said singer Carrie Smith, who grew up in Newark and now lives in East Orange. "If you had any talent at all, you came through Newark and [then] you’d go to New York. Little Jimmy Scott, all those cats, everybody came through Newark.”

A kind of synergy with New York fed the Newark scene. "There were a lot of people from Jersey that hung out in New York to get inspiration from the city,” said jazz singer-pianist Andy Bey, a Newark native who began performing at age five and like Vaughn, attended the city’s famed Arts High School. "But Newark had its own thing because it wasn’t as competitive in a sense, it was a small town where you could work and survive, because there was always something to play.” Jersey also benefited from New York’s law banning performers with criminal records from playing there. Stars like Billie Holiday and Charlie Parker came across the river to perform. Parker made his first record with his own band in Newark, with the Savoy Record Company, in November 1946. The band: Dizzy Gillespie, Max Roach, and Miles Davis.

Later, in the 1960s, Newark became a stop on the "Chitlin’ Circuit,” a network of nightclubs and bars in cities like Buffalo, Cleveland, and Philadelphia, featuring mostly black performers playing for black customers. The Hammond organ became a signature sound on the scene, after jazz musicians like Wild Bill Davis and Bill Doggett co-opted the instrument from black churches. "Newark had a jazz club on every other corner and that [organ jazz] was really the thing out there. They were trying to make it go over big,” said Jimmy McGriff, a renowned jazz organist who began playing Newark in 1959. He wistfully remembers the clubs on the circuit: Sparky J’s, Midas Gold, Mr. Wes, The Key Club. "You had to work Newark, no way around it,” said McGriff. All those clubs were gone by the early 1980s, as the music’s popularity waned.

Other New Jersey industrial cities can boast of notable jazz pasts, too. "The city of Paterson had a booming, groovy jazz scene going in the 1920s Jazz Age,” said Terence Ripmaster, a former history professor at William Paterson University. Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway played Paterson’s Alexander Hamilton Hotel in the 1930s and 1940s. At Sandy’s Hollywood Brick Bar in Paterson, crowds—including a young guitarist named Bucky Pizzarelli—gathered to hear the great Joe Mooney, a blind man who could play the accordion with one hand and also played organ and piano. The music tradition seeped into nearby Clifton in the 1960s, with the opening of the Clifton Tap Room. By then, interest in jazz was on the wane and top stars would come to Paterson for little pay, including Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster, and Sonny Rollins, said the club’s owner, Amos Kaune. Atlantic City was also a jazz destination for decades, where acts like Willis "Gatortail” Jackson played in the 1960s. Sammy Davis, Jr., Carmen McRae, Cannonball Adderley, and Slide Hampton all played clubs there, and Count Basie and Duke Ellington performed at the famous Steel Pier.

The 1980s were quiet years for jazz, but educational programs continued to develop and today attract students from around the country and even the world. The state boasts two universities offering respected jazz education programs: Rutgers and William Paterson. The world’s largest public-access jazz archive is in Newark at Rutgers University, as is one of the nation’s best-known jazz radio stations, WBGO-FM (88.3). In 1997, Rutgers began offering a master’s degree in jazz history and research. Today scores of jazz musicians, many of them also teachers at these and other schools, call the state home. They cite its proximity to New York, plus a lively smattering of jazz clubs, festivals, and new and old fans around to keep the music alive. Nowadays, jazz is not as popular and Jersey cities do not often draw top talent. But the state lays claim to a rich history and a legacy that began in the early days of the jazz age.

Jefferson. 42-square-mile township in Morris County. Jefferson was formed from portions of Roxbury and Pequannock townships in 1804. Located in the rugged central Highlands, it includes both densely developed areas and large tracts of open space. Iron mining and forging played an important role in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with at least eight forges in operation here. The mountainous terrain rendered agriculture of lesser importance. In the twentieth century, Jefferson has seen the development of numerous lake communities, as well as the establishment of large areas of open space for recreation and water supply. Mahlon Dickerson Reservation was named after a New Jersey governor, a native of the town. Much of the northern portion of the township is occupied by the Pequannock Watershed and Oak Ridge Reservoir. The southern portion of the town borders on Lake Hopatcong. In 2000, the pop-ulation of 19,717 was 96 percent white. The median household income in 2000 was $68,837.