Alpine. 6.37-square-mile borough in Bergen County. Located along the Hudson River atop the Palisades, Alpine is one of the wealthiest communities in the nation. It was originally part of Hackensack Township (1693-1775) and later part of Harrington Township (1775-1903); Alpine Borough was incorporated in 1903. In 1904 the eastern portion of Cresskill was ceded to Alpine. The borough was known as Upper Closter until the i870s, and the origin of Alpine’s name is uncertain, deriving from either Closter’s Alpine Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons or the Swiss Alps. Alpine was originally a farming community, but the blasting of traprock from the Palisades cliffs was its major industry until 1900. The fishing industry flourished into the middle of the twentieth century.

Today it is overwhelmingly residential and has few businesses and no industry. Opulent estates in luxury subdivisions predominate, while more modest middle-class homes survive in the Old Alpine neighborhood. With few municipal programs, the borough’s property taxes are among the lowest in the state. More than half of the borough’s land remains undeveloped as part of the Palisades Interstate Park Commission system, Alpine Boy Scout Camp, and borough parks.

In 2000, the population of 2,183 was 77 percent white and 19 percent Asian. The 2000 median household income was $130,740.

Amber. Amber is the hardened residue of ancient tree sap. Much valued from antiquity to the present as a gemstone, amber is made into a variety of decorative objects. In ancient times, well-established trade routes for amber originated from the Baltic countries (where amber was plentiful along the coast) that went to virtually every corner of Europe. Early in the nineteenth century, the first reports of amber from North America came from discoveries in New Jersey along Crosswicks Creek near Trenton, at Camden, and near Woodbury.

Most of the amber found in New Jersey is from sedimentary deposits of the Late Cretaceous age, the last part of the age of dinosaurs. The strip of Cretaceous rocks producing amber stretches from Raritan Bay in the northeast diagonally southwest across the state to the Delaware River. Amber is especially abundant in the Magothy Formation, a sequence of clays and sands laid down in coastal rivers and floodplains about ninety-five millionyears ago. In 1967 this deposit produced the oldest known fossil ants (engulfed by the flowing resin of ancient sap-producing trees and preserved when the resin turned to solid amber), a species named Specomyrma freyi by the Harvard entomologist E. O. Wilson. Since then amber from this formation has been extensively collected at Sayreville in Middlesex County, where it has produced representatives of thirty families of arthropods, including the oldest known true ants, bees, wasps, cockroaches, flies, midges, lacewings, leafhoppers, mites, spiders, and pseudoscor-pions. True rarities from this site are the oldest known feathers of birds from North America. The Sayreville amber deposit is one of the most significant concentrations of Cretaceous fossil insects in the world.

American Aluminum Company. American Aluminum was founded in 1910 by Henry Brucker, a Newark native. Brucker had previously served as superintendent of the New Jersey Aluminum Company, and won a medal at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904. In 1910, Brucker set up his own shop with his brother Oscar on Oliver Street in Newark, expanding to a larger factory on Jelliff Avenue in 1916. The firm produced a wide range of household and industrial products. In 1956 the American Aluminum Company moved to a new factory in Mountainside, where it remains today.

American Boychoir School. The only nonsectarian choir boarding school in the United States, the American Boychoir School is built on the conviction that musical performance is a means of building character and motivating academic achievement. Founded in 1937, the school moved to New Jersey in 1950 and occupies the former Lambert estate in Princeton. Each year, eighty boys in grades five through eight come together from across the country to attend the school. While completing a comprehensive academic program—and winning admission to prestigious secondary schools—they sing 175 concerts annually, performing regularly with the world’s finest orchestras and in festivals overseas.

American Can Company. Founded in New Jersey in 1901 by Edward and Oliver W. Norton and nurtured by area food manufacturers, the American Can Company grew prosperously throughout the first half of the twentieth century. During the 1950s, the company sought to diversify through a wide-ranging series of acquisitions and ventures into paper, chemicals, commercial printing, and glass bottle manufacturing. Beneficial developments in can technology, such as the pop-top and ring-tab opener, counterbalanced AmCan’s less successful ventures such as chemicals, commercial printing, and glass bottle-making. Inevitably, the company’s inexperience would force them to divest these ventures. Subsequent acquisitions involving aluminum recycling and resource recovery, as well as smaller concerns such as records and mail-order retail products, again produced varied results. In 1978, AmCan designed a computerized system to rank investment risks in seventy countries. The sale of the company’s forest products operations during the early 1980s financed the acquisition of four insurance companies, most notably American General Capital Corporation and Associated Madison. Chairman Gerald Tsai severed AmCan’s ties to its can-making business in 1986 by selling the packaging operations to Triangle Industries. He restructured the company into a financial services conglomerate, renamed Primerica, with headquarters in Greenwich, Connecticut. Successive alliances and mergers with Travelers Corporation and Citibank led to the creation of Citigroup.

American Chemical Society. The American Chemical Society (ACS), founded in 1876, is now the world’s largest scientific society, with over 163,000 members in 2001. Reflecting the high concentration of chemical and pharmaceutical operations in New Jersey (both commercial and academic), there are nine local sections (or chapters) of the ACS in the state. The North Jersey Section has the distinction of having the largest membership (more than 7,400) of any of the 189 local sections in the United States. Some representative functions of the New Jersey ACS sections include sponsoring awards to individual chemists for distinguished accomplishments in the field (most notably the Baekeland Award), supporting educational programs that advance the study of chemistry, and providing forums for the presentation and discussion of current research topics.

American Federation of Labor. At an 1881 Pittsburgh conference, delegates from a variety of workers’ organizations formed the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions in the United States and Canada; it reorganized in 1886 as the American Federation of Labor (AFL). From the start it stood in stark contrast to its predecessor, the Knights of Labor, which had attempted to organize all workers, skilled and unskilled. By 1886, however, the Knights organization was devastated by losses of crucial strikes and the Haymarket riot. Into the fray stepped the AFL, which sought to create a craft-based organization that would capitalize on the power of skilled workers. This approach of "pure and simple” unionism was to characterize the AFL’s approach for decades to come.

Samuel Gompers served as president of the AFL from 1886 until his death in 1924. In that time, this former cigarmaker determined a new course for the American labor movement. Whereas the Knights had included unskilled workers, women, African Americans, and immigrants in their ranks, Gompers’s AFL excluded those workers on the pretext that they could be used by employers to undermine skilled trade workers. Under his leadership, the AFL championed an exclusionary form of unionism that was far more restrictive and conservative than other efforts to realize industrial unionism.

Despite a major defeat in the 1892 Homestead strike, the AFL not only weathered the depression of the 1890s but grew to encompass some 264,000 members by 1897—a membership it more than tripled by 1904. In New Jersey, the AFL successfully organized scores of skilled workers in the metal, printing, and building trades. These workers pressed for better work conditions, increased pay, and decreased work hours for themselves, though the majority of New Jersey’s unskilled laborers did not share in these gains. Indeed, the AFL’s failure to represent most industrial workers helped to pave the way for other more inclusive unions. Thus, although the AFL-affiliated United Textile Workers included a few of Paterson’s silk workers, it was the militant Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) that most prominently supported the laborers in their famous 1913 strike.

The AFL continued to expand, but by the beginning of the twentieth century the industrial world itself was changing significantly: skilled workers increasingly found themselves displaced and faced crushing defeats in actions including the 1901 strike against U.S. Steel. To widen its sphere of influence, the AFL increasingly turned to collective bargaining, no-strike contracts, and the use of union labels to designate union-produced goods. Although the AFL did not represent most of New Jersey’s workers (84 percent of whom were not unionized), it did represent 123,000 of the state’s 200,000 unionized workers before World War II.

Under the leadership of Gompers’s successors, William Green and George Meany, the AFL eventually emerged as the largest union in the United States and boasted some 10 million members when it merged in 1955 with the advocate of industrial unionism, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO).

American Indians. The Lenape, whose name means "the people” or "common folk,” once occupied all of present-day New Jersey, eastern Pennsylvania, northern Delaware, southeastern New York State (including western Long Island and Staten Island), and parts of western Connecticut. This area was called "Lenapehoking,” meaning "the land of the Lenape.” The bands who lived north of the Raritan River and Delaware Water Gap spoke a Munsee dialect of the Delaware language and developed a culture somewhat different from that of the Unami speakers who lived to the south. Those who spoke a northern Unami dialect, sometimes identified as Unalachtigo, lived in and around Easton, Pennsylvania, and in adjacent parts of New Jersey. Increasingly after 1664, the English called the Lenape "Delaware Indians” because many were then living along the river and bay named after Lord De La Warr.

In the archaeological record, the Lenape become recognizable after c. 900 c.e. Before then, Lenapehoking was occupied by cultures identified only by generic names assigned by archaeologists: Paleo-Indians, Archaic Indians, Early, Middle, and Late Woodland Indians. Some of these may have been ancestors of the Lenape.

Paleo-Indians (c. 10000-8000 b.c.e.) entered New Jersey following the retreat of the Wisconsin glacier. The park tundra environment of that time supported mastodon, mammoth, sloth, caribou, and walrus, among other cold-adapted animals. How often early hunters killed mastodon is unknown, but their exquisitely crafted fluted spearpoints were efficient weapons. Knives, choppers, scrapers, and drills were made with equal care, using only the best stones.

Throughout the Archaic period (c. 80001000 b.c.e.), forests yielded nuts and berries that helped to sustain human beings and provided mast foods for deer, bear, turkeys, and other forest-edge animals. Trees could also be made into dugout canoes and shelters, and they provided firewood for warmth and cooking. Stone axes, adzes, and gouges, first made in Archaic times, were essential for felling trees. Women also used these tools to chop firewood, crack bones in order to extract marrow, and perform other domestic chores.

Spearpoints, essential to the hunt, were made in many shapes and sizes. Fastened to long shafts, they were thrown with a catapultlike atlatl, or spear-thrower. Mounted into short handles, such points served equally well as knives. Traps and snares were also set to capture game, and fish were caught in nets and weirs. Slain animals provided meat, skin for clothing and containers, sinew and gut for sewing and binding, bones and antlers for tools, and hooves from which to make glue and rattles. Almost nothing was wasted.

Women and children contributed significantly by gathering plants, fruits, seeds, roots, tubers, berries, nuts, birds’ eggs, shellfish, crustaceans, turtles, frogs, and other edible or useful things. Seeds and nuts were ground into flour using milling stones and handheld mortars and pestles. Foods were eaten raw or roasted, as ceramic cooking pots were unknown to Archaic people. However, cooking may have been accomplished by placing water, meat, fish, and plant ingredients in skin or bark containers and immersing fire-heated stones into the liquid—a process called "stone-boiling.” Toward the end of the Archaic period, about 2000 b.c.e., people began carving stone bowls out of soapstone and talc. These could be placed on or over a fire without cracking. Clay pots also appeared about this time.

Houses were probably ephemeral, because Archaic people moved frequently, depending on available food and resources. In mountainous places, rock shelters and caves were occupied during hunting and gathering forays. On coastal plains, huts were probably made from saplings covered with mats or skins.

Early and Middle Woodland cultures (c. 1000 B.c.E-900 c.e.) were remarkable for their sometimes elaborate burials, often accompanied by copper artifacts from Lake Superior, shells from the Gulf Coast, fine stones from faraway places like Labrador and the Dakotas, and other exotic objects. With such burials, archaeologists have found the first evidence of woven cloth and tobacco pipes. During Middle Woodland times (c. 500 c.e.) the bow and arrow replaced the spear as the preferred hunting weapon.

Lenape Indians are usually identified with the Late Woodland period (c. 900-1600 c.e.). Dependable and storable garden vegetables were added to foods obtained by hunting, fishing, and gathering. Garden crops included corn, beans, squash, and possibly sunflower and tobacco. The need to tend gardens required the construction of more permanent and substantial houses and storage facilities. After crops were harvested and stored, hunting and nut-gathering forays were undertaken. Edible American chestnuts abounded and, together with certain acorns and other nuts, provided easily procurable foods that helped to sustain the bands throughout the winter. Deer and bear were hunted more intensively in cold weather, when they had grown fat and their pelts were thick and warm. Elderly and infirm persons were always provided for, as sharing was an essential part of Lenape life.

Lenape people lived seemingly tranquil lives in small, unfortified communities; there is no archaeological evidence of warfare until after European colonists arrived. Houses were constructed from saplings stuck into the earth at opposite sides and bent together at the top to form a dome-shaped trellis tied with bast fibers. Beginning at the bottom and overlapping one another, rectangular slabs of tree bark were tied to the frame to provide a secure, watertight cover. Openings in the roof vented smoke. A single doorway provided entrance. Raised platforms along the inside walls of the house were covered with skins or furs and provided seating during the day and sleeping places at night. Firewood and stored foods were probably kept under the bunks, and bundles of tobacco and herbs were suspended from roof poles. Storage pits lined with bark and mold-resistant grass were located at the ends of large houses for easy access to dried meats and plant foods in bad weather. Similar storage pits, suitably covered against rain or snow, were located outside the dwellings. Round-ended longhouses might measure sixty feet in length and twenty feet in width; wigwams were usually smaller and more circular. Historic accounts indicate that twenty-five or more people might occupy a single longhouse.

Lenape lived in small bands near streams, lakes, and seashores. Each band operated independently, there being no centralized political authority and no chiefs before the coming of Europeans. Clan identities included the wolf, turtle, and turkey. Every person belonged to one such descent group, which served to regulate marriage, among other things. For example, a woman was expected to marry a man from a lineage other than her own; their children kept the mother’s lineage. Should anything happen to the parents, members of the mother’s lineage would care for the children.

Marriage was simple, oftentimes nothing more than an agreement to live together. Initially, the couple resided in the woman’s house, which was likely shared by her mother, sisters, and their respective husbands and children. Gender division characterized labor within the society. Women cared for the children and performed domestic chores, tanned hides, made clothing, fashioned pottery vessels, tended gardens, gathered firewood, and, accompanied by children, foraged for edible plants, nuts, shellfish, and other foods. Men hunted, fished, and did heavy physical work. They cut down and burned sections of the forest to provide clearings, tilled the garden soils, made dugout canoes, cut saplings and bark for house construction, chipped stone tools and weapons, and made wooden bowls and ladles.

Surviving skeletal remains indicate that Lenape people were healthy, although increasing consumption of garden foods, high in sugar and starch, resulted in more tooth decay and abscesses. Herbal teas and poultices were used for internal disorders and topical applications. Every woman knew the properties of common medications, but herbalists with special skills were highly regarded. To be effective, herbal remedies, whether made from plants, roots, leaves, or bark, had to be gathered in a ritually prescribed manner. When found, the spirit of the herbal plant was prayed to and informed of the condition to be alleviated.

Death often came at an early age. Infant mortality was particularly high. Burials usually occurred on the day following death. Shallow graves accommodated bodies placed in a flexed position, with knees drawn up and arms folded. The elaborate offerings found in Early and Middle Woodland graves were seldom included, although the Lenape held a "Feast of the Dead” on the day of burial and on subsequent anniversaries.

A very spiritual people, the Lenape believed in a single, all-powerful, creative force who "creates us by his thoughts.” Prayers and supplications had to be recited twelve times before reaching the twelfth heaven, where Kishelemakong, the supreme deity, resided. Having created the universe and all good things, Kishelemakong delegated the maintenance of the system to lesser spirit beings. Among these were thunder beings, sun, moon, stars, and corn mother. Mesingw, "the Keeper the "Delaware Tribe of Western Oklahoma.” The "Stockbridge Munsee” live near Green Bay, Wisconsin, and still other Lenape reside in Moravian town and Munsee Town, Ontario, among the Six Nations in Canada, and elsewhere. Small numbers of Delaware remained in New Jersey, where they intermarried with other Native Americans and people of European and African American descent. Many have lost their identity, though others are members of groups claiming long-established histories in the state. There is also a growing number of individuals of questionable descent who for one reason or another desire to be identified as Lenape or Delaware. The Oklahoma and Canadian Delawares do not recognize these persons.

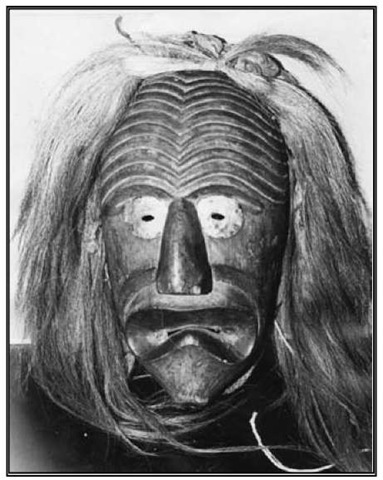

Carved wooden mask with sheet-metal eyes and tressed with horsehair, possibly representing Mesingw, the Keeper of the Game, who protected forest animals, nineteenth century.

The counterpart to the beneficent creator who provided wholesome and useful things was Mahtantu, who put thorns on berry bushes, created poisonous snakes, spread useless plants, and caused other undesirable things. Mahtantu was not a devil in the Christian sense, for he did not consign men’s souls to everlasting damnation. In fact, the Lenape had no conception of hell. Rather, evildoers would be barred from participation in the pain-free afterlife that good people would enjoy in a provident and pleasant place. Relationships to spirit beings were individual and personal; there were few prescribed prayers or rituals. Certain occasions— for example, the Corn Dance, or fall harvest ceremony—required the participation of all members of the community, as did the later Big House ceremony.

An essential rite, especially for boys, was the Vision Quest, wherein an aspiring youth was led into the woods or mountains without food. Alone and afraid, he prayed that some spirit—a bird, animal, or insect—would pity him and agree to serve as his guardian. Those who failed in this endeavor often considered themselves unworthy and bereft of spiritual protection. A girl, favored with a vision when sick and delirious, was considered to be especially blessed and was often encouraged to become a herbalist.

The seemingly uncomplicated and satisfying life of the Lenape changed with the arrival of European traders, who offered iron axes, knives, brass pots, glass beads, and other useful and desirable things in exchange for pelts. Beaver, otter, and other fur-bearing animals were hunted relentlessly—not for food or clothing, but solely to satisfy the Europeans’ insatiable demands and to acquire trade items. When overhunting reduced the number of furs, traders stopped providing rum and trade goods, leaving the Indians frustrated and angry. Alcohol and drugs were unknown before European contact, and the introduction of rum and beer wreaked havoc among native people unaccustomed to intoxicants. Unwittingly, Europeans also introduced epidemic diseases. Native people had never been exposed to such deadly pathogens and had no immunity to them. According to some estimates, epidemic diseases annihilated up to 90 percent of the native populations, often destroying entire villages.

Under intense pressure to sell their lands, weakened and dispirited, the Indians saw no way to survive and maintain their traditional culture amid the growing population of unsympathetic and self-serving European immigrants. To preserve themselves and their culture, the Indians moved westward, only to become embroiled in the French and Indian War, Pontiac’s Rebellion, the Revolutionary War, and other struggles that further diminished their numbers. The 1758 treaties of Crosswicks and Easton offered small compensations to the Indians in return for quitclaims to all their remaining lands in New Jersey. At that time, too, the Brotherton Reservation was established in Burlington County for the benefit of Christianized Lenape living south of the Raritan River. This, the first and only Indian reservation in New Jersey, was dissolved in 1801, and the last native population moved into New York State and eventually to Wisconsin and Kansas.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the Lenape, often called "Delaware Indians,” are among the most fragmented of all Indian peoples. The majority live in northeastern Oklahoma, where they are identified as the "Delaware Tribe of Indians,” and in western Oklahoma, where they are known as American Labor Museum/Botto House National Landmark. Thismuseum and education center in Haledon presents public exhibits, classes, lectures, artistic performances, and outreach programs in the fields of labor and immigrant studies. It is a nonprofit membership institution that was founded in 1983 by a consortium of community, business, and labor leaders. The American Labor Museum is one of a growing number of museums throughout the world that are dedicated to celebrating the history and contribution of working people.

The Botto House, home of the museum, is a twelve-room, three-family Victorian house built in 1908 by Pietro (1864-1945) and Maria (1870-1915) Botto, immigrants from Biella, Italy. A trolley-car suburb, Haledon was home to working families employed in neighboring Paterson, which was known as "Silk City.” Pietro Botto was a skilled weaver, and Maria was a silk inspector who worked at home on a "picking frame.” During the 1913 Paterson Silk Strike, the house became a haven for free speech and assembly for over twenty thousand strikers who were forbidden to meet in Paterson. This strike was one of several historic events that led to labor legislation and improvements in working conditions.

![tmp7-20_thumb[1] tmp7-20_thumb[1]](http://what-when-how.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/tmp720_thumb1_thumb.jpg)

![tmp7-22_thumb[1] tmp7-22_thumb[1]](http://what-when-how.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/tmp722_thumb1_thumb.jpg)