American Littoral Society. Based in Sandy Hook, the American Littoral Society (ALS) is a national, nonprofit environmental watchdog group with more than six thousand members. It was founded in 1962 by fishermen and divers worried about development and water quality; since then the ALS has played a role in the enactment of key legislation affecting littoral areas (such as the Wetlands Act, the Coastal Facility Review Act, and the Waterfront Development Act).

The ALS supports free public access to beaches, the removal of structures such as jetties, groins, and bulkheads, and the buyout of beachfront and other property subjected to frequent flooding and storm damage. The society has consistently objected to tax-funded beach replenishment. Two society projects concentrate on New Jersey watersheds: the Baykeeper is an advocate for the Hudson-Raritan Estuary at the mouth of New York Harbor, and the Delaware Riverkeeper keeps an eye on that river’s lands and waters.

American Pottery Manufacturing Company. Located in Jersey City, the American Pottery Manufacturing Company was the first U.S. pottery manufacturer to introduce English factory methods using molds and a division of labor. In 1828, Scottish brothers David and James Henderson, operating as D. and J. Henderson, employed English master potters William and James Taylor to make brown-glazed stoneware vessels in a factory previously built and occupied by the Jersey Porcelain and Earthenware Company on the block bounded by Essex, Sussex, and Warren streets. In 1833, the name was changed to the American Pottery Manufacturing Company (also known as the American Pottery Company), and David Henderson took control of the operation. By this time, the company had introduced the extensive use of press molds, first utilizing molds acquired from England and, later, employing master mold-makers like Englishman Daniel Greatbach.

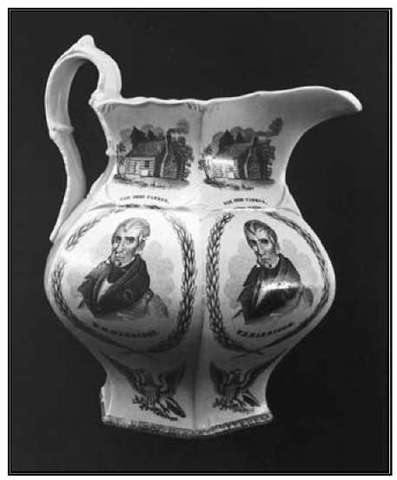

Earthenware pitcher with cream background and black transfer prints made by the American Pottery Manufacturing Company for William Henry Harrison’s presidential campaign, 1840.

Products included brown-glazed stonewares, yellow earthenware, and refined white earthenware. Much of the white earthenware was transfer printed, a process in which elaborate decoration is transferred from engraved copper plates to the pottery surface. The company is known for its use of the Canova pattern copied from English originals. It decorated hexagonal pitchers for the presidential campaign of William Henry Harrison in 1840 with transfer prints of Harrison and his log cabin symbol. White wares were embellished with blue color sponged onto the surface. Plates and teapots marked by the American Pottery Company are known by this decoration. Many wares, however, may have survived without marks and may be identified as English products today. The company is known primarily for its hound-handled pitchers with low-relief hunt scenes on the sides. Many of these were covered with a Rockingham glaze, which is distinguished by a dark brown spotted appearance. Developed in England, this type of glaze was introduced to American manufacture about 1840 and persisted through the nineteenth century.

In 1845, David Henderson was killed in an accident in the Adirondack Mountains. The surviving corporate owners of the company, including William Rhodes, Oliver Strong, and Thomas McGerron, continued to make similar wares and probably also used the same company name. By 1870, however, the pottery was owned by John Owen Rouse and Nathaniel Turner, and was called the Jersey City Pottery Company. They continued to make Rocking-ham household wares, such as pitchers and teapots, including their own version of the so-called Rebekah-at-the-Well pattern. The pottery also produced a line of white granite tableware, although few marked examples have survived and the full range of this line is not known today. During the 1880s, it made a line of cream-colored earthenware in ornamental shapes, called ivory whiteware, which was sold undecorated, for embellishment by independent china decorators across the United States. Turner died in 1884. Rouse sold the property in 1892. The buildings were demolished shortly thereafter.

During David Henderson’s tenure, the pottery was at the forefront of the American ceramics market. From 1828 to 1845, the company’s wares competed favorably with English imported stoneware and earthenware. After the Civil War, however, the pottery’s products were uninspired.

American Repertory Ballet/ Princeton Ballet School. The American Repertory Ballet (ARB) is New Jersey’s largest dance company. The Princeton Ballet Society maintains both the ARB and its affiliate, the Princeton Ballet School.

Audree Estey, a former actress-dancer for Fox Studio and a renowned ballet teacher, founded the Princeton Ballet School in 1954. More than twelve hundred students now study at its studios in Princeton, Cranbury, and New Brunswick, making it one of the largest dance schools in the nation. The school offers a wide-ranging curriculum, conservatory atmosphere, and apprenticeship program in order to provide the training that will help guide its students to careers as professional dancers.

In 1968, the success of the Princeton Ballet School led Estey to establish the Princeton Regional Ballet Company, which, in 1978, became the professional Princeton Ballet Company. Its growing national reputation inspired the name change, in 1991, to the American Repertory Ballet. The company’s home theaters are the New Brunswick State Theatre and McCarter Theatre in Princeton. The ARB is also a principal affiliate of the New Jersey Performing Arts Center. Since 1987, the New Jersey State Council on the Arts has designated the company a Major Arts Institution and, in addition, awarded the ARB a citation of excellence for 1998-2000.

American Revolution. The worst crisis to strike the state of New Jersey was also its first crisis—the Revolutionary War of 1775-1783. New Jersey was a corridor between the northern and southern colonies and between the two key cities of New York and Philadelphia. Many of the crucial military actions of the Revolution took place in New Jersey, and the small and sparsely populated state suffered a disproportionate share of the war’s battles, invasions, and civil strife. Through the years of war, George Washington spent more time in New Jersey than in any other state, including three winter encampments (Morristown in 1777 and 1779-1780 and Raritan in 1778-1779). For New Jerseyans, the home front and the battlefront were often the same.

Prior to its major role in the Revolution, New Jersey played a relatively minor part in the decade of protest that preceded the outbreak of war. With a population of about 117,000, the colony had no large cities to match Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, with their urban mobs, and no large merchant class that bridled at limits imposed by Britain on commerce with Europe and the West Indies. Unlike many other colonies, New Jersey made no claims to western territories and so did not suffer from British limitations on settlement beyond the Allegheny Mountains. The colony had no newspaper to rally public opinion, and it produced no leaders with the influence of Patrick Henry of Virginia or Samuel Adams of Massachusetts. In 1765, at the beginning of the protest movement, New Jersey’s legislature initially turned down a request to send delegates to an intercolonial conference called to protest the Stamp Act.

Although the colony was not in the forefront of the protest, a majority of New Jerseyans came to share with other colonists the sentiment that restrictive legislation passed by Parliament posed a threat to liberty. One issue that agitated the colony was Britain’s limitation on the issuance of paper currency, a move that disadvantaged New Jersey’s debtor farmers. The colony sent delegates to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, and residents engaged in protest activities such as hanging unpopular officials in effigy, boycotting British imports, holding anti-British meetings, and forming Sons of Liberty groups. Inspired by events in Boston, a mob in Greenwich destroyed a cargo of British tea.

As in other colonies, rebel New Jerseyans set up an extralegal government of local committees, and they formed a colonywide Provincial Congress to which towns sent representatives. By 1775, this ad hoc structure had taken charge of the affairs of the colony in place of the increasingly isolated royal governor, William Franklin, and his officials. But unlike more militant colonies in the South and New England, New Jerseyans still hung back from calling for a complete break with Great Britain. Even as late as January 1776, nine months after armed conflict began at Lexington and Concord, most New Jerseyans did not favor independence.

The turning point for New Jersey came in June 1776, when the Provincial Congress arrested Governor Franklin and removed him from office. In July the rebels adopted a constitution that declared New Jersey’s independence and replaced the old colonial government. This hastily written document continued to refer to New Jersey as a colony, rather than a state, and contained a final clause that provided for its own nullification in the case of reconciliation between England and its colonies. But for all the hesitancy, the crucial step had been taken: New Jersey was independent.

The constitution provided for a governor to be elected annually by the legislature. As the first occupant of that office, the legislature chose William Livingston, a retired lawyer and fervent revolutionary. Livingston proved to be an excellent war leader and was reelected each succeeding year.

The newly formed state government faced serious problems. First was the presence of a large Tory faction, perhaps one-third of the population, which remained loyal to the Crown and regarded the rebels as traitors. Another block of New Jerseyans, the Quakers, though not overt supporters of the British, followed their pacifist religious principles and declared themselves neutral in the war.

A second problem was to provide regiments of regular troops for the Continental Army and to raise an effective state militia. This manpower problem was never satisfactorily solved, and throughout the war New Jersey struggled to recruit and maintain soldiers. The Jersey militia had a poor reputation in the eyes of General Washington.

The third and most pressing threat facing Livingston and the new government came from the British Army, which had captured New York City in August 1776 and threatened to invade New Jersey. The invasion came on the morning of November 20, 1776, when a force of six thousand men under the command of Maj. Gen. Charles Cornwallis crossed the Hudson from Manhattan and climbed the Palisades. Gen. William Howe’s army captured Fort Lee, the main rebel stronghold on the west bank of the Hudson River, and then relentlessly advanced south through the length of New Jersey in pursuit of George Washington and the Continental Army.

The retreat across New Jersey from late November through late December 1776 marked the lowest point of the American Revolution. Washington’s shrinking, poorly clad, and poorly equipped force, virtually abandoned by the New Jersey militia, could not stop the British juggernaut. Washington was forced to flee across the Delaware to Pennsylvania, leaving the enemy in possession of the major towns of New Jersey. Governor Livingston and the state legislature went into hiding. Under British occupation, many former rebels signed loyalty oaths to the Crown.

But then came a master stroke. On Christmas night 1776, Washington and approximately twenty-four hundred soldiers crossed the Delaware River and the next morning routed the Hessian garrison at Trenton, killing the commander and capturing almost one thousand prisoners. The Battle of Trenton was a momentous victory that helped to keep the American cause alive. A week later, Washington defeated the British at Princeton, enabling him to reestablish the presence of the Continental Army in New Jersey.

The victories at Trenton and Princeton forced the British to close ranks in a few heavily garrisoned towns, and they withdrew almost entirely from New Jersey in 1777. Civil authority was restored. Although the remaining years of the Revolution were difficult in New Jersey, the situation never reached the depths of defeat and disunity that marked the perilous days of late 1776.

In the late summer of 1777 Howe tried another strategy. He occupied Philadelphia, driving out the Continental Congress. But the Americans blocked the Delaware River south of Philadelphia through fortifications on islands in the river and at Fort Mercer on the Jersey side. A fierce British and Hessian attack on Fort Mercer was repulsed in October. The Delaware eventually did fall to Howe, but his occupation of Philadelphia failed to extinguish the rebellion.

In June 1778 Henry Clinton, Howe’s successor in command of the Crown forces, evacuated Philadelphia, marching across New Jersey toward New York City with some ten thousand British and Hessian soldiers. Presented with an opportunity to strike a blow at the enemy, Washington set out in pursuit, this time assisted by the New Jersey militia, which harassed the British line of march. Washington finally caught up with the British Army at Monmouth Courthouse on June 28, 1778. The Battle of Monmouth was inconclusive, but the American force showed that it could stand head-to-head against the British.

One final large-scale invasion of New Jersey occurred in June 1780, when a force of five thousand British and Hessian soldiers under Gen. Wilhelm von Knyphausen landed near Elizabethtown. American resistance forced Knyphausen to turn back, but not before his soldiers set fire to the towns of Connecticut Farms and Springfield.

New Jerseyans suffered much from these military campaigns, invasions, and encampments. Soldiers from both armies requisitioned property and routinely stole livestock to fill their bellies and fences to fuel their fires. The British and their allies committed the most serious depredations, and episodes of pillaging were common. Even after regular troops left the area as the major focus of the war shifted from the mid-Atlantic to the southern colonies, New Jerseyans lived in fear of Tory raids. New York City remained in British hands until the end of the war, giving the Tories a safe base from which to launch assaults. Virtually no county in New Jersey was untouched by civil strife, but the bloodiest were Bergen and Monmouth counties, where vigilante bands of Tories and rebels committed atrocities against each other. The rebels had the government on their side and used the law to banish or execute Loyalists and confiscate their estates.

There was more to the Revolution than war. The state’s first newspaper, the New-Jersey Gazette, was established in December 1777, and its pages became a forum where residents could express their views about maintaining revolutionary virtue, about the need for vigilance against the enemy, and about the ramifications of independence for religion and education. One remarkable exchange in the paper in 1780-1781 addressed the question of whether slavery was compatible with the ideals of the Revolution—a debate that one historian has described as "the most extensive conducted in any state prior to the 1830s.”

During the war, New Jerseyans were also concerned about the organization of a national government. The state legislature approved the Articles of Confederation in November 1778, but expressed serious reservations about the potential for large states to dominate the smaller ones. New Jersey’s representatives would grapple with this vexing issue a decade later in the debate over the federal Constitution.

When the war finally ended in 1783, New Jersey was left devastated and impoverished. The currency was hopelessly inflated; farms, churches, and homes had been burned to the ground; and families and communities had been torn apart by bitterness between Loyalists and rebels. But for all the difficulty, the war had been won, and New Jersey could chart its own future as a state within the new American nation.

Historians have long debated the nature of the American Revolution. Was it a conservative movement to preserve the rights Americans already enjoyed? Was it a class war between haves and have-nots? Did it unleash a new revolutionary ideology? Looked at from the perspective of little New Jersey, the war’s origins were deeply conservative. There was no intent to turn the world upside down; no conscious change occurred in the relationship between rich and poor, masters and slaves, or men and women. One of New Jersey’s military leaders, William Alexander, proudly claimed to be the heir to a British noble title and was deferentially referred to as "Lord Stirling.” No New Jerseyans objected to having this aspiring aristocrat in their midst.

But in the debates in the Gazette and in private letters and public legislation one can see a radical view of the political and social order emerging. At the end of the war, Governor Livingston spoke to the General Assembly and, through that legislative body, to the people of New Jersey: "Let us now shew ourselves worthy of the inestimable Blessings of Freedom by an inflexible Attachment to publick Faith and national Honour. Let us establish our Character as a Sovereign State on the only durable Basis of impartial and universal Justice.” The revolutionary implication was that, from the eminent Lord Stirling to the humblest resident, New Jerseyans were equal in the eyes of the state. It is a concept that continues to challenge the people of the state in the third century since the Revolution.

![tmp7-24_thumb[1] tmp7-24_thumb[1]](http://what-when-how.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/tmp724_thumb1_thumb.jpg)

![tmp7-25_thumb[1] tmp7-25_thumb[1]](http://what-when-how.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/tmp725_thumb1_thumb.jpg)