Eastern, or Wind River, Shoshone, a group grounded in Great Basin traditions who modified their culture to include elements from Plains and postcontact cultures. The Comanche broke away from the Eastern Shoshone about 1700 and moved south toward Texas (see Comanche [Chapter 6]). The term "Shoshone" is of dubious origin and was not a self-designation.

Location The Eastern Shoshone lived in western Wyoming from at least the sixteenth century on, expanded well into the northern Great Plains through the eighteenth century, and then retreated in the nineteenth century. They were loosely divided into two groups: Mountain Sheep Eaters to the north and west and Buffalo Eaters to the east and south. Most Eastern Shoshones now live on the Wind River Reservation, in Fremont and Hot Springs Counties, Wyoming.

Population There were perhaps 3,000 Eastern Shoshones in 1840. In 1990, 5,674 Eastern Shoshones and Arapahos lived on the Wind River Reservation.

Language The Eastern Shoshones spoke dialects of Shoshone, a Central Numic (Shoshonean) language of the Uto-Aztecan language family.

Historical Information

History Beginning at least as early as 1500, the Comanche-Shoshone began expanding eastward onto the Great Plains and adopting wide-scale buffalo hunting. With the acquisition of horses, about 1700, they also began widespread raiding and developed a much stronger and more centralized leadership. It was roughly at this time that the Comanche departed for places south. Armed (with firearms), the Blackfeet and other tribes began driving the Eastern Shoshone off the westward plains beginning in the late eighteenth century. Major smallpox epidemics occurred during that period, and the Eastern Shoshone adopted the Sun Dance introduced around 1800. Extensive intermarriage also occurred with the Crow, Nez Perce, and Metis.

During most of the nineteenth century, the Eastern Shoshone, under their chief, Washakie, were often allied with whites and grew prosperous. During the peak of the fur trade, from 1810 to 1840, the Eastern Shoshone sold up to 2,000 buffalo skins a year. When settlers began pouring into their territory in the 1850s, the Eastern Shoshone, under Washakie, tried to accommodate. In the Fort Bridger Treaty of 1868 they received 44 million acres; this figure was later reduced to fewer than 2 million. During the next 15 or so years they lived in a roughly traditional way on their reservation.

Because the Shoshone fought with the U.S. Army against the Lakota on many occasions, they felt betrayed when the government placed the Arapaho, their traditional enemies, on their reservation in 1878. The disappearance of the buffalo in the 1880s spelled the end of their traditional way of life. From the late nineteenth century and into the mid-twentieth century, the Eastern Shoshone, now confined to reservations, experienced extreme hardship, population loss, and cultural decline. They had no decent land, hunting was prohibited, government rations were issued at starvation levels, and they could find no off-reservation employment because of poor transportation and white prejudice. Disease, especially tuberculosis, was rampant. Life expectancy was roughly 22 years at that time. The Indian Service controlled the reservation

A slow recovery began in late 1930s. Land claims victories brought vastly more land as well as an infusion of cash (almost $3.5 million). Concurrently, the tribal council, hitherto relatively weak, began assuming greater control of all aspects of reservation life. By the mid-1960s, the incidence of disease was markedly lower, owing in large part to the diligent efforts of women. Indicators such as housing, diet, economic resources (such as oil and gas leases), education, and real political control had all increased. Life expectancy had risen to 40-45 years. Traditional religious activity remained strong and meaningful. And yet severe and ongoing problems remained, including continuing white prejudice and a corresponding lack of off-reservation job opportunities, outmigration, slow economic development, and fear of the growing strength of the Arapaho.

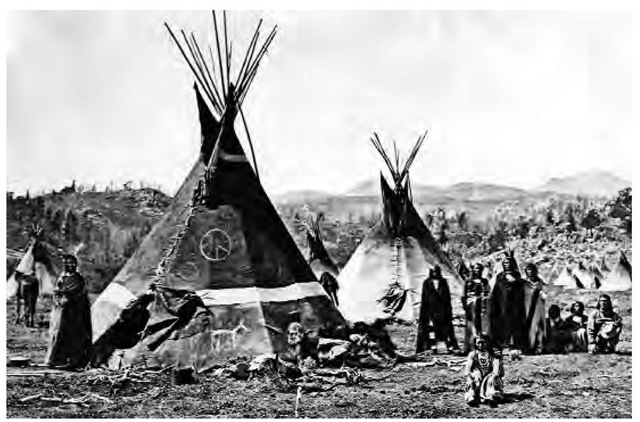

During most of the nineteenth century, the Eastern Shoshone, under Chief Washakie, were often allied with whites and grew prosperous. Pictured here is Chief Washakie’s village near the Sweetwater River in Wyoming, 1870.

Religion The Eastern Shoshone knew two basic kinds of religious practice. One was aimed at an individual’s obtaining the assistance of supernatural powers from spirits. In exchange for power, such spirits, which could also be dangerous, demanded adherence to strict behavioral taboos. Power was gained either through dances or by sleeping in sacred places. Success in obtaining power was marked by a vision through which the power transferred skills or protections as well as songs, fetishes, and taboos. Power might also be transferred from one shaman to another by blowing. Should a person’s power depart, a shaman had to recapture it lest the person die. Shamans did not so much control power as they were dependent on it.

The other kind of religious practice was designed to ensure the welfare of the community and nature as a whole by the observance of group ceremonials. The Father, the Shuffling (Ghost), and the Sun Dances were all addressed toward beneficent beings. The first two, during which men and women sang sacred songs, often took place at night in any season except summer. The Shuffling Dance was particularly important to Mountain Sheep Eaters.

The four-night and three-day Sun Dance was held in summer and featured exhaustion owing to dancing and lack of water. Introduced from the Plains around 1800, it symbolized the power and cohesion of the tribe and of the generations. It was an occasion for demonstrating virility, courage, and supernatural powers. Male dancers first participated in ritual sweats and other preparations, which began as early as the preceding winter. The ceremony itself, held around ten outer poles encircling a buffalo head mounted on a center pole, was followed by a great feast of buffalo tongues. Little boys were charged with grabbing the tongues.

Spirit places, things, and people were inherently dangerous and included ghosts, whirlwinds, old or menstruating women, death, and illness. Illness was seen as coming from either a breach of taboo or malevolent spirits. Sacred items and activities included sweating, burning certain grasses and wood, smoking wild tobacco, eagle feathers, paints, and certain songs. The peyote cult began on the reservation around 1900.

Government Centralization was the key to successful buffalo hunting and warfare and thus to eighteenth-and nineteenth-century Eastern Shoshone survival. During prosperous times (for instance, those with strong chieftainships) and when they came together seasonally as a tribe (for instance, for the spring buffalo hunt and the summer Sun Dance), the Eastern Shoshone numbered between 1,500 and 3,000.

A chief was at least middle-aged and of military or shamanistic training. He had authority over hunting, migration, and other issues. He and his assistants controlled the two military-police societies. His several distinctions included possessing a painted tipi and a special feathered headdress. He also acted as chief diplomat for external disputes.

The Eastern Shoshone separated into between three and five bands in winter, camping mainly in the Wind River Valley. Each band had a chief as well as military societies. Bands were loosely identified with particular geographic regions. Membership fluctuated, with extended family groups joining different Shoshone bands or perhaps even bands of other tribes such as the Crow.

Customs Women were in general subordinate to men, chiefly because menstruation set them apart as sources of ritual pollution. The younger wife or wives usually suffered in instances of polygyny. Widows were dispossessed. At the same time, women gained status as individuals through their skills as gatherers, crafters, gamblers, midwives, and child care providers. Particularly during the fur trade, alliances with white trappers and traders were made with daughters and sisters, leading to important interethnic ties.

Social status positions were earned through the use (or nonuse) of supernatural power, except that age and sex also played a role. Infants and small children were not recognized as sexually different. Boys began their search for supernatural power around adolescence. "Men" were those who were married and members of a military society.

Girls helped their mothers until marriage, which was arranged shortly after the onset of puberty. Menstrual restrictions included gathering firewood (a key female chore) and refraining from meat and daytime sleeping. A good husband was a good provider, although he might be considerably older.

Wealth and prestige accrued to curers; midwives; good gamblers; hunters and traders; and fast runners. Property was often destroyed or abandoned at death. Generosity was a central value: Giveaways for meritorious occasions were common. Men cared for war and buffalo horses, women for packhorses. High-stakes gambling games included the hand and four-stick dice game, double-ball shinny (women), and foot races.

Dwellings After the move onto the Plains, women made buffalo skin tipis according to a strenuous, time-consuming procedure. Men decorated the tipis. Beds, a central fireplace, and parfleches filled the inside. The master bed had a decorated antelope hide or two.

Diet Bands engaged in small-scale hunting and gathering in summer; buffalo were hunted communally in spring and especially in fall. Staples included buffalo, elk, beaver, mule deer, antelope, mountain sheep, moose, bear, jackrabbit, and smaller game. The winter diet relied heavy on dried buffalo (pemmican). Trout and other fish, caught in spring, were also a staple. Fish were eaten fresh or sun dried or smoked for storage. Important plants included camas, wild onion, berries, and sunflower seeds.

Key Technology Most goods were made from animal (especially the buffalo) and plant materials as well as minerals such as flint, obsidian, slate, and steatite. Every part of the buffalo was used, including the dung (for fuel). In the historic period, iron from non-native traders became very important.

Fishing equipment included traps, weirs, dams, and spears. Roots in particular were cooked in earth ovens. Food was kept in leather parfleches. Men prepared shields, hide drums, and rattles; women made most other leather work, such as tipis, clothing, containers, and trade items. They also made coiled baskets.

With counting sticks, Eastern Shoshones could keep track of numbers up to 100,000.

Trade Perhaps the largest regional intertribal trade gathering was held in midsummer at Green River, Wyoming.

Notable Arts Art objects were made from a variety of materials, including stone, wood, and clay. Leather goods included tipis, parfleches, shields, and other items. Elkhides were painted to depict important events such as Sun Dances, buffalo hunts, and warfare. The best-made goods were often decorated with beads or drilled elk’s teeth. People made pictographs at the sites of particularly sacred places.

Transportation Eastern Shoshones had the horse from about 1700 on. A horse (formerly dog)-drawn travois transported the infirm as well as households. Dogs aided in transportation, hunting, and war. Snowshoes were worn for winter hunting.

Dress Most clothing and blankets were made of buffalo and other hides. With their eastern expansion, the Eastern Shoshone adopted Plains fringed-and-beaded styles.

War and Weapons Beginning in the eighteenth century, the state of war was more or less continuous, and warfare took a great toll on the Eastern Shoshone. There were two military societies. About 100-150 brave young men were Yellow Brows. The recruitment ritual included backwards speech (no for yes, for example). This fearless society acted as vanguards on the march. They fought to the death in combat and had a major role keeping order on the buffalo hunt. Their Big Horse Dance was a highly ritualistic preparation for battle. Logs were older men who took up the rear on the march. Both groups were entitled to blacken their faces.

Shamans participated in war by foretelling events and curing men and horses. As many as 300 men might make up a war party. Traditional enemies included the Blackfeet and later the Arapaho, Lakota, Cheyenne, and Gros Ventre. During the mid- to late nineteenth century, the principal ally of the Shoshone was the U.S. Army.

Spring and especially fall were the time for war. At these times the Eastern Shoshone generally fought as a tribe. Men made handle-held shields from thick, young buffalo bull hide. Rituals and feasting accompanied their manufacture. Each was decorated with buckskin and fringed with feathers. Weapons included sinew-backed bows, obsidian-tipped arrows, and clubs. Successful warriors were entitled to paint black and red finger marks on their tipi. Warriors occasionally committed suicide in combat.

Contemporary Information

Government/Reservations The Wind River Reservation (1863; Shoshone and Arapaho Tribes), Fremont and Hot Springs Counties, Wyoming, has 2,268,008 acres and a population of 5,674 Indians (1990). Both tribes have business councils.

Economy Major activities are ranching, crafts, and clerical jobs. Some people regularly hunt and fish. There is income from mineral leases; the Eastern Shoshone tribe is a member of the Council of Energy Resource Tribes (CERT). Un- and underemployment is chronically high.

Legal Status The Arapaho Tribe of the Wind River Reservation and the Shoshone Tribe of the Wind River Reservation are federally recognized tribal entities.

Daily Life Quasi-traditional religion remains important. The Sun Dance has been explicitly Christianized and is now intertribal. Only a few Mountain Sheep Eaters practice the Shuffle Dance. Peyotism is popular. Giveaways, formerly related to public coup counting, are now associated with other occasions. Shoshone language courses are taught at the Wyoming Indian High School, located on the reservation. Housing, most of which consists of modern "bungalows," is considered generally inadequate. The people use canvas tipis for ceremonial purposes.

High rates of substance abuse and suicide plague the reservation; accidents have replaced disease as primary killers. Outmigration remains a problem. Women have more freedom as well as political and social power, obtained in part through their participation in certain musical ceremonies. Wyoming Indian High School is Arapaho-dominated; most Shoshone attend off-reservation public high schools. Traditional games such as the hand game, with its associated gambling, remain popular, especially at powwows. Many people still speak the language.