Lakota, a Siouan dialect spoken by the Western or Teton (Titunwan, "prairie dwellers") group of the tribe commonly referred to as Sioux. The subdivisions of the Western group include Oglala ("they scatter their own"), Sicangu ("burned thighs"; also known by the French name Brule), Hunkpapa ("end village"), Minneconjou ("plant beside the stream"), Itazipco ("no bows"; also known by the French name Sans Arcs), Sihasapa ("black feet"), and O’ohenonpa ("two kettles").

The Lakota refer to themselves as Lakota ("ally"), as Lakotah Oyate ("Lakota People"), or as Ikce Wicasa ("Natural" or "Free People"). The word "Sioux" is derived originally from an Ojibwa word, Nadowe-is-iw, meaning "lesser adder" ("enemy" is the implication) that was corrupted by French voyageurs to Nadousssioux and then shortened to Sioux. Today, many people use the term "Dakota" or, less commonly, "Lakota" to refer to all Sioux people.

All 13 subdivisions of Dakota-Lakota-Nakota speakers ("Sioux") were known as Oceti Sakowin, or Seven Council Fires, a term referring to their seven political divisions: Teton (the Western group, speakers of Lakota); Sisseton, Wahpeton, Wahpukute, and Mdewakanton (the Eastern group, speakers of Dakota); and Yankton and Yanktonai (the Central, or Wiciyela, group, speakers of Dakota and Nakota). See also Dakota; Nakota.

Location In the late seventeenth century, the Lakota lived in north-central Minnesota, around Mille Lacs, and parts of Wisconsin. By the mid-nineteenth century they had migrated to the western Dakotas, northwestern Nebraska, northeastern Wyoming, and southeastern Montana. Today, most Lakotas live on reservations in South Dakota as well in as regional and national cities. Many Lakotas leave the reservation to find work but return for summer visits and, often, to retire.

Population Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota speakers numbered approximately 25,000 in the late eighteenth century; almost half of these were probably Lakotas. In the mid-1990s there were roughly 55,000 Lakotas living on U.S. reservations, mostly Oglalas at Pine Ridge and Sicangus at Rosebud. There were 103,255 "Sioux" people in the United States, according to the 1990 census.

Language The Western group speaks the Lakota dialect of Dakota, a Siouan language.

Historical Information

History The Siouan language family may have originated along the lower Mississippi River or in eastern Texas. They migrated to, or may have originated in, the Ohio Valley, where they lived in large agricultural settlements. They may have been related to the Mound Builder culture of the ninth through twelfth centuries. The Siouans may also have originated in the upper Mississippi Valley or even the Atlantic seaboard.

Siouan tribes still lived in the southeast, between Florida and Virginia, around the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century. All were destroyed either by attacks from Algonquian-speaking Indians and/or a combination of attacks from non-Indians and non-Indian diseases. Some fled and were absorbed by other tribes. Some were sent as slaves to the West Indies.

Dakota-Lakota-Nakota speakers inhabited over 100 million acres, mostly prairie, in the upper Mississippi region, including Minnesota and parts of Wisconsin, Iowa and the Dakotas, in the sixteenth to early seventeenth century. They largely kept clear of the British-French struggles. Conflict with the Cree and Anishinabe, who were well armed with French rifles, plus the lure of great buffalo herds to feed their expanding population, induced bands to begin moving west onto the Plains in the mid-seventeenth century. The Teton migration may have begun in the late seventeenth century, in the form of extended hunting parties into the James River basin.

Lakotas acquired horses around 1740; shortly after that time the first Teton bands crossed the Missouri River. They entered the Black Hills region around 1775, ultimately displacing the Cheyenne and Kiowa, and made it their spiritual center. As more and more Teton bands became Plains dwellers (almost all by 1830), they helped establish the classic Plains culture, which featured highly organized bands, almost complete dependence on the buffalo, and a central role for raiding and fighting. The Teton subdivided into their seven bands during that time.

In 1792 the Lakota defeated the Arikara Confederacy, allowing the Lakota to expand into the Missouri Valley and western South Dakota. In 1814 they concluded a treaty with the Kiowa marking boundaries between the two peoples, including recognition that the Lakota now controlled the Black Hills (known to them as Paha Sapa). By that time, at the latest, the Lakota were well armed with rifles.

Around 1822, the Lakota joined with the Cheyenne to drive the Crow out of eastern Wyoming north of the Platte. During that period, Tetons were engaged in supplying furs for non-Indians, although contacts were usually limited to trading posts, particularly Fort Laramie after 1834 and the Oglala move to the Upper Platte region. In the 1840s, wagon trains passing through Teton territory began disrupting the buffalo herds, and the Indians began attacking the wagons. In the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty, the Indians agreed to give the wagons free access in exchange for official recognition of Indian territory.

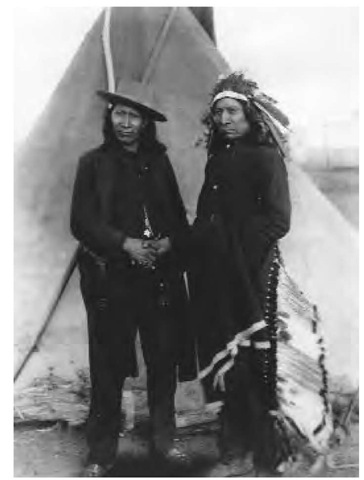

In the early to mid-1860s, the Oglala chief Red Cloud (Makhpiya-luta), pictured on the right in 1891, led and ultimately won a brutal and protracted fight to force the U.S. government to close the Bozeman Road through the Powder River country, the last great hunting ground of the Lakota.

Conflict continued throughout the 1850s. In one series of incidents, in which a group of Sicangu ate and offered to pay for a stray Mormon cow, the U.S. Army attacked Sicangu villages and killed over 100 people. In the early to mid-1860s, the Oglala chief Red Cloud (Makhpiya-luta) led and ultimately won a brutal and protracted fight to force the United States to close the Bozeman Road through the Powder River country, the last great hunting ground of the Lakota. The road through it had been opened illegally as a route to newly discovered gold fields in Montana; it crossed Teton territory without their permission, in violation of the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty. Fighting with the Tetons were Northern Cheyennes under their leader, Dull Knife, as well as Northern Arapahos.

The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty was an admission by the United States of the Indian victory in the so-called Red Cloud’s war. The government agreed to close the Bozeman Road and stay out of Teton territory. In exchange, the Indians agreed to stop their raids and remain on a "Great Sioux Reservation." Both Red Cloud and the Sicangu leader Spotted Tail remained committed to peace, although they often spoke against easy accommodation to U.S. terms.

In 1874, gold was discovered in the Black Hills during an illegal military expedition. This event brought swarms of miners and other non-Indians, in direct violation of the treaty. With Red Cloud and Spotted Tail settled on reservations, it fell to new leaders, young and free, such as the medicine man Sitting Bull (Tatanka Yotanka) and Crazy Horse (Tashunka Witco), to protect the sacred and legally recognized Teton lands against invasion. The United States rebuffed all Indian protests, and the Indians rejected U.S. efforts to purchase the Black Hills.

In 1876, army units ceased protecting the Black Hills against non-Indian interlopers and went after Teton bands who refused to settle (which they were under no obligation to do under the terms of the Fort Laramie Treaty). In March, Tetons under Crazy Horse repelled an attack led by Colonel Joseph Reynolds. At Rosebud Creek the following June, Crazy Horse and his people routed a large force of soldiers as well as Crow and Shoshone scouts under the command of General George Crook. Later that month, Teton and Cheyenne Indians led by Oglalas under Crazy Horse and Hunkpapas under Sitting Bull and Gaul wiped out the U.S. Seventh Cavalry, under General George Custer, at the Little Bighorn River.

Here the Indian victories came to an end. The army defeated a large force of Cheyennes in July, and in September General Crook’s soldiers captured a combined force of Oglalas and Minneconjous under American Horse. Two months later, Dull Knife and his Northern Cheyennes lost an important battle, and Crazy Horse himself was defeated in January 1877 by General Nelson Miles. Finally, Miles defeated Lame Deer’s Minneconjou band in May 1877. Meanwhile, Sitting Bull, tired of the military harassment, had taken his people north to Canada. With his people tired and starving, Crazy Horse surrendered in April 1877. In August he was placed under arrest and was assassinated on September 5. He is still regarded as a symbol of the Lakotas’ heroic resistance and as their greatest leader.

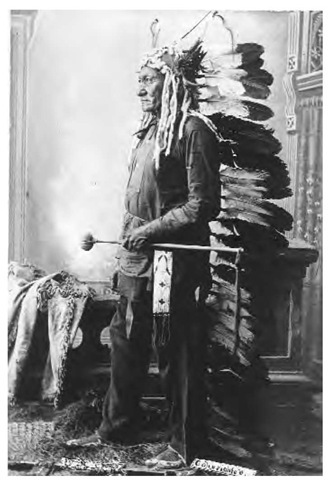

With Red Cloud and Spotted Tail settled on reservations, it fell to new leaders such as the medicine man Sitting Bull (pictured here) to protect the sacred and legally recognized Teton lands against invasion.

Defeated militarily and under threat of mass removal to the Indian Territory, Red Cloud, Spotted Tail, and the other Lakota and Santee chiefs signed the treaty ceding the Black Hills and the Powder River country. Shortly thereafter, the army confiscated all Lakota weapons and horses and then drove the people into exile to reservations along the Missouri River.

After unilateral "cessions" in 1877, the Great Sioux Reservation consisted of 35,000 square miles of land, but a coalition of non-Indians, including railroad promoters and land speculators, maneuvered to break up this parcel. Meanwhile, Canada proved completely inhospitable to the exiled Lakota, and gradually they began drifting back to the United States. Sitting Bull returned to formal surrender in 1881.

The giant land grab came in 1888, when the United States proposed to carve the great reservation up into six smaller ones, leaving about nine million acres open for non-Indian settlement. The government unsuccessfully offered the Lakota $.50 an acre for the land. They then offered $1.50 an acre and prepared to move unilaterally if this offer were to be rejected. The government needed three-quarters of the adult male votes for approval. Despite the opposition of Red Cloud, about half of the Oglalas signed the treaty. With Spotted Tail dead (he had been assassinated in 1881), most of the Sicangu signed. Sitting Bull was the loudest voice opposed, but he was physically restrained from attending a meeting presided over by accommodationist chiefs, and the signatures were collected. The Great Sioux Reservation was no more.

Deprived of their livelihood, Lakotas quickly became dependent on inadequate and irregular U.S. rations. The United States also undermined traditional leadership and created their own subservient power structure. A crisis ensued in 1889 when the government cut off all rations. The general confusion provided fertile ground for the Ghost Dance.

In 1888, a Northern Paiute named Wovoka, building on previous traditions, popularized a new religion that came to be called the Ghost Dance (see Paiute, Northern [Chapter 4]). Wovoka foretold the return of an Indian paradise if people would pray, dance, and abandon the ways of non-Indians. The new religion gave hope to many Native Americans whose societies by this time had reached a crisis point, and it quickly spread over much of the West. Many Indians also thought special Ghost Shirts could stop bullets.

Fearing that the Ghost Dance would encourage a new Indian militancy and solidarity, white officials banned the practice. In defiance, Oglala leaders in 1890 planned a large gathering on the Pine Ridge Reservation. To keep Sitting Bull, the last strong Lakota leader, from attending, the Indian police arrested him in December. During the arrest he was shot and killed.

The Minneconjou leader Big Foot once supported the dance, and for this reason General Miles ordered his arrest. Big Foot led his band of about 350 people to Pine Ridge to join Red Cloud and others who advocated peace with the United States. The army intercepted him along the way and ordered him to stop at Wounded Knee Creek. The next morning (December 29) the soldiers moved in to disarm the Indians. When a rifle accidentally fired into the air, the soldiers opened fire with the four Hotchkiss cannon on the bluffs overlooking the camp, killing between 260 and 300 Indians, mostly women and children. The Wounded Knee massacre marked the symbolic end of large-scale Native American armed resistance in the United States.

Dead Indians are frozen in the ice the morning after the Battle of Wounded Knee, 1890. The Wounded Knee massacre remains very much in the hearts and minds of Lakotas, with many annual remembrance ceremonies and pilgrimages to the site. The Wounded Knee massacre marked the symbolic end of large-scale Native American armed resistance in the United States.

From the 1880s into the 1950s, most Lakota children were forced to attend mission or Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) schools, There the children were taught menial skills, and their culture was violently repressed. During the twentieth century, tip is slowly gave way to government-issue tents and then log cabins. Many Lakotas became Catholics or Episcopalians, although traditional customs and religious practices also continued, including the officially banned Sun Dance.

Bands were broken up, in part by the allotment process. As the United States worked to replace traditional leadership, education, religion, and other cultural and political structures, Lakota society underwent a profound demoralization. Most Lakota were fed government-issue beef, which they had trouble eating after a steady diet of buffalo. In general, government rations were of low quality and quantity.

Lakotas were ordered to begin raising cattle. Despite some success in the early twentieth century, U.S. agents encouraged them in 1917 to sell their herds and lease their lands to non-Indians. When the lessees defaulted in 1921, the government urged Indians to sell their allotments for cash. By the 1930s, devoid of cattle and land, general destitution had set in.

Indians stand guard outside the Sacred Heart Catholic Church in Wounded Knee, March 3, 1973. This was the scene of a violent confrontation between the American Indian Movement (AIM), called in to protect the people against abuses, and tribal forces supported by U.S. military power.

Lakotas adopted the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934, after which reservations were governed by an elected tribal council, although the traditional system of chief-led tiyospayes (subbands) was still in place. A tribal court system handled minor problems; more serious offenses fell under the control of the U.S. court system.

Native Americans were part of the ethnic pride movement of the 1960s. The Red Power movement had its origins in the formation of the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) in 1944. In 1972, many Lakotas participated in a march to Washington, D.C., called the Trail of Broken Treaties, during which they took over the BIA.

The following January, under the leadership of the American Indian Movement (AIM), several hundred Pine Ridge Lakotas attempted to end and reverse U.S.-sponsored corruption on Pine Ridge, particularly the strong-arm tactics of the tribal chair at that time. The context was decades of poverty and frustration on the reservation. The government responded with a massive show of force. During the 71-day siege, known as Wounded Knee II, two Indians were killed by federal agents. The event forged a new solidarity among Lakotas and other Indians but also left deep scars among the reservation population.