INTRODUCTION

Canada spans 9,976,140 square kilometers and has an approximate population of 32 million people (Statistics Canada, 2001). More than 90% of Canada’s geography is considered rural or remote (Government of Canada, 2001). Despite the highly dispersed population, and, indeed, because of it, Canada is committed to the idea that a networked telehealth system could provide better access and equity of care to Canadians. Growing evidence of the feasibility and affordability of telehealth applications substantiates Canada’s responsibility to promote and to develop telehealth.

Telehealth is the use of advanced telecommunication technologies to exchange health in formation and provide healthcare services across geographic, time, social, and cultural barriers (Reid, 1996). According to a systematic review of telehealth projects in different countries (Jennett et al., 2003a, 2003b), specific telehealth applications have shown significant socioeconomic benefits to patients and families, healthcare providers, and the healthcare system. Implementing telehealth can impact the delivery of health services by increasing access, improving quality of care, and enhancing social support (Bashshur, Reardon, & Shannon, 2001; Jennett et al., 2003a). It also has the potential to impact skills training of the health workforce by increasing educational opportunities (Jennett et al., 2003a; Watanabe, Jennett, & Watson, 1999). Therefore, telehealth has a strong potential to influence improved health outcomes in the population (Jennett et al., 2003a, 2003b).

Fourteen health jurisdictions—one federal, 10 provincial, and three territorial—are responsible for the policies and infrastructure associated with healthcare delivery in Canada. This article presents a telehealth case study in one of Canada’s health jurisdictions—the province of Alberta. The rollout of telehealth in Alberta serves as an example of best practice. Significant milestones and lessons learned are presented. Progress toward the integration of the telehealth network into a wider province-wide health information network also is highlighted.

BACKGROUND

Canada’s province of Alberta has a geography that is well suited to using telehealth technologies. Previous telehealth pilot projects throughout the province provided evidence of potential benefits from telehealth applications (Doze & Simpson, 1997; Jennett, Hall, Watanabe, & Morin, 1995; Watanabe, 1997). Alberta is the westernmost of Canada’s prairie provinces with a total area of 661,188 km2. Approximately 3 million people live in this western province, with two-thirds of the population living in two major cities in the lower half of the province; 19.1% of the population is distributed over the northern remote areas and southern rural communities (Figure 1) (Alberta Municipal Affairs, 2004; Statistics Canada, 2001).

In Alberta, health regions assume responsibility for acute care facilities and continuing and community-based care facilities, including public health programs and surveillance. The population sizes of health regions vary, as do their service census populations (Figure 1). The province has approximately 100 hospitals and more than 150 long-term care facilities. Health professionals are located largely in the urban centers, leaving many rural and remote areas with limited access to a variety of healthcare providers and services. In the mid-1990s, there was a physician-to-population ratio of 1:624 (Alberta Health, 1996). Most physicians are compensated on a fee-for-service basis by the provincial government (Alberta Health, 1997).

During the last decade, health reforms and restructuring have taken place in Canada, both at the federal (Kirby, 2002; National Forum on Health, 1997; Romanow, 2002) and provincial (Clair, 2000; Fyke, 2001; Mazankowski, 2001; Ontario Health Services Restructuring Commission, 2000) levels. These reforms were conducted in response to important trends challenging the Canadian Medicare system, such as escalating costs for new technologies and drugs, aging population, and increasing public expectations. Furthermore, health reforms addressed the issue of access to healthcare services for some groups, such as Aboriginal people and populations living in rural and remote parts of the country (Romanow, 2002).

Major challenges include the scarcity and isolation of healthcare professionals in many communities because of Alberta’s large landmass; varied, extreme, and unpredictable climate; and population dispersion. Such realities were recognized as principal factors motivating the consideration of a provincial health information network. Alberta began to plan such a network in the mid-1990s, with the objectives of exploiting health information technologies and linking physicians, allied health professionals, hospitals, clinics, health organizations, and Alberta Health and Wellness (the provincial government’s department of health) (Government of Alberta, 2003; Jennett, Kulas, Mok, & Watanabe, 1998). This network, entitled Alberta Wellnet, was a joint initiative by Alberta Health and Wellness and stakeholders in the health system. Initially, a core set of priority initiatives consisted of a pharmacy information network, telehealth, a healthcare provider office system, continuing and community care services, service event extract, population health and surveillance, and diagnostic services information sharing. This article describes the development of the provincial telehealth network in Alberta.

Figure 1. Health regions in Alberta

|

Health Region |

Region # on Map of Alberta |

Population* |

% of Alberta Population |

# of Video-conference Sites |

|

Chinook |

R1 |

152,636 |

4.9 |

8 |

|

Palliser |

R2 |

98,074 |

3.1 |

9 |

|

Calgary |

R3 |

1,122,303 |

35.9 |

34 |

|

David Thompson |

R4 |

286,211 |

9.2 |

27 |

|

East Central |

R5 |

109,981 |

3.5 |

10 |

|

Capital Health |

R6 |

978,048 |

31.3 |

28 |

|

Aspen |

R7 |

176,580 |

5.7 |

18 |

|

Peace Country |

R8 |

130,848 |

4.2 |

24 |

|

Northern Lights |

R9 |

69,063 |

2.2 |

16 |

|

Total |

3,123,744 |

100 |

174 |

|

THE PROVINCIAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE TELEHEALTH NETWORK

Just prior to the establishment of Alberta Wellnet, an anonymous philanthropic foundation expressed interest in exploring the feasibility of developing an integrated, province-wide telehealth network based on need, capability and support. One of the authors (ES) initiated discussions with the foundation through an intermediary, and a small team of content experts was assembled to begin dialogue. The foundation requested a letter of intent and a presentation of concept to substantiate the benefits of allocating funds to telehealth. Following internal review and external consultation, the foundation allocated $525,000 for the preparation of a telehealth business plan. A project planning team was formed to serve as the province-wide planning group and to oversee the preparation of the business plan. This team incorporated representatives from the RHAs, the health sector, the universities, and the community. Two province-wide focus groups were held with representatives from the stakeholder groups to discuss content and approach, and a number of meetings were held between the CEOs (chief executive officers), their RHAs, and boards. The 17 regions and the two provincial boards at that time indicated their support in principle for a provincial telehealth network. The foundation’s acceptance of the Provincial Telehealth Business Plan provided a commitment of up to $14 million to fund a provincial telehealth network pursuant to the satisfaction of a number of conditions (Table 1). The milestones associated with the development of the network are outlined in Table 2.

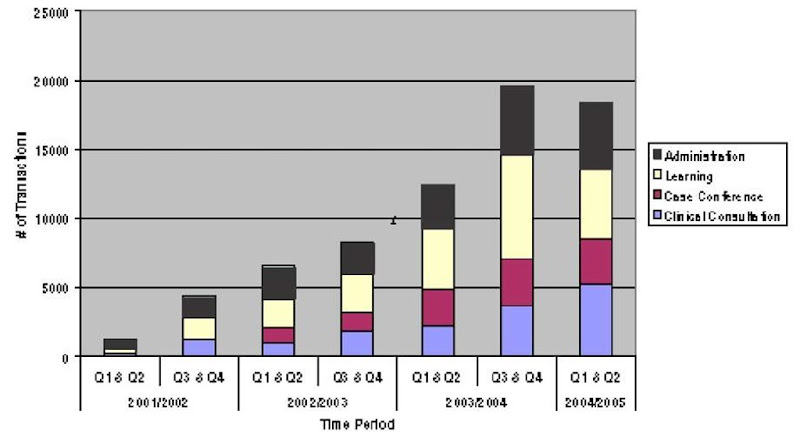

Specifically, the provincial telehealth network began its rollout in 1999 and continues to evolve and develop. A Provincial Telehealth Committee (PTC) comprised of health region, physician, and Alberta Health and Wellness representatives was formed in 1999 to provide strategic direction to this provincial initiative. Figure 1 outlines the current status of the network. In October 2004, there were 261 active telehealth systems that were networked and centrally connected through a network consisting of a combination of ISDN, SW56, and AGNPac. Applications were clinical, educational, and administrative in nature, and sessions were charted between 2002 and 2004 (Figure 2). In 2004, the network’s 10,000th clinical consultation occurred, and clinical services were extended to the First Nations’ communities.

Table 1. Donor foundation conditions

• Funds to be used for capital purposes only

• 2 to 1 matching funds required ($7,000,000)

• Province-wide network (a minimum of 75% of the population, at least 12 Health Regions)

• Improve access (remove distance, especially for remote, isolated rural)

• Incorporation of all current pilot projects

• Sustainable, integrated into the health information system

Table 2. Milestones

1994 Health reform and restructuring in Alberta established 17 Regional Health Authorities (RHAs), down from >200.

1995 An anonymous philanthropic donor foundation expressed interest in exploring the feasibility of developing an integrated province-wide telehealth network based on need, feasibility, and support.

1996 Initial Business Plan supported the concept of a provincial telehealth plan. Potential allocation of $14 million, providing a number of conditions could be met.

1996 Initial plans for a provincial health information network (Alberta Wellnet) began.

1997 Telehealth Coordination (ATCC) and Implementation Planning Committees (ATIPT) formed with action plans regarding policy, infrastructure implementation, and operational solutions. Vision and overall management Report produced by the Telehealth Working Committee, with input from all stakeholders.

1997 $7 million one-time commitment, plus $1 million operating costs commitment from Alberta Health.

1997 Provincial Health Authorities’ Association re-established a Charitable Foundation to receive and administer funds.

1997-8 The Alberta Medical Association’s Committee on Fees and Alberta Health opened the way to potential payment for telehealth services.

1997-8 Telehealth handbook compiled to provide guidelines for Regions initiating telehealth activities. ATIPT merged with ATCC.

1998 Joint Planning Committee held with Alberta Telehealth Coordinating Committee (ATCC), the RHAs, and the Provincial Boards resulting in four priority telehealth applications: psychiatry; emergency care; radiology; and continuing education. Frameworks for three issues were discussed: 1) Needs assessment models, 2) Funding models, and 3) Provincial telehealth infrastructure and network.

1998 “Decision Document” produced for the Minister of Health, the RHAs, the anonymous philanthropic foundation, and the Alberta Medical Association. Business models for the four priority areas evolved, along with working groups assigned to each.

1999-00 Establishment of Provincial Telehealth Committee and coordinator.

1999-04 Central support services were initiated and deployed, including an interoperability standard testing framework for vendors, a scheduling system, followed by bridging and gatewaying services, and core evaluation and costing frameworks, processes, and tools.

2003 Alberta’s RHAs reduced from 17 to 9 Health Regions.

2003 30 different clinical disciplines included in Telehealth.

2003-6 Provincial Telehealth Strategic Business Plan approved. Five critical success factors were articulated. A number of proposed initiatives were put in place.

2003-6 Telehealth Clinical Grant Fund established. Two calls for proposals have occurred, resulting in the funding of approximately 20 clinical projects and anticipated approval for an additional 20 projects.

2004 10,000th telehealth clinical consultation occurred.

2004 Clinical telehealth service extended to First Nations Communities.

2004 Telehealth scheduling system extended to the Territory of Nunavut.

2004 First provincial clinical telehealth forum held. Second one approved for 2005.

Figure 2. Growth of Telehealth—Increased administrative, learning, case conference, and clinical consultation transactions

Since 2001, central supporting services have been established to support all stakeholders. For example, an Internet-based telehealth scheduling system initially was deployed in 2001 to facilitate coordination of telehealth activities throughout the province and has been used successfully to support approximately 30,000 telehealth events. The system now is being shared with several otherjurisdictions (Nunavut, Saskatchewan, some mental health sites in British Columbia, Alberta First Nation’s and Inuit Health Branch sites). Other core services included an interoperability standards testing site for vendors at Alberta Research Council, bridging and gatewaying services as well as costing models and core evaluation frameworks. For example, a home telehealth business case template was completed to facilitate health region analysis of this mode of service, while a newly developed site-based costing model provided support for further research and the development of a sustainable economic model for telehealth in Alberta. Further, a comprehensive provincial evaluation process is in development. To this end, an Inventory of Telehealth Evaluation Activities in Alberta was completed in order to establish a baseline and to inform refinements to the existing evaluation framework. Associated indicator standards are being aligned with the Alberta Health and Wellness Quality Framework. The Health Information Standards Committee of Alberta recently approved a new Alberta telehealth videoconferencing standard, as technological standards are continuously evolving.

A Provincial Telehealth Strategic Business Plan (2003-2006), developed by the PTC on behalf of health regions and approved by the Council of CEOs, articulates five critical success factors to realize the full potential of the Alberta Telehealth network. These five foci include (1) providing timely access to quality care, (2) collaborating effectively, (3) securing and effectively managing resources, (4) creating a culture that fosters change, and (5) formalizing the evaluation process and enhancing telehealth research.

At present, all of Alberta’s Health Regions have telehealth programs in place. Due to required health system and provider buy-in rate, the clinical applications were slightly slower to evolve. As a consequence, a project that established incentives for the development of clinical telehealth applications was initiated. Alberta Health and Wellness funded a Telehealth Clinical Grant Fund (overseen by the PTC) resulting in more than 20 clinical telehealth projects, including cardiology, emergency, diabetes, urgent mental health, and pediatric services. A recent call for proposals is expected to result in funding of 20 additional projects, some of which will be extended to First Nations Communities.

SIGNIFICANT LESSONS LEARNED AND OBSERVATIONS

There were many lessons learned during the development of the Provincial Telehealth Program. They fall into two broad categories: (1) Business, Funding, and Sustainability (four items) and (2) Policy, Operational, and Infrastructure Issues (15 items) (Table 3). A number of key observations also emerged. These included the need to:

• Understand the nature and the implications of health reform and restructuring;

• Identify and clarify policy and operational issues around specific applications;

• Incorporate adequate telecommunications infrastructure;

• Respect diversity in priorities as well as preparedness and state of readiness among Health Regions;

• Ensure provision for sustainable operational support; support preparation of business models for shared telehealth needs in the Health Regions;

• Pay special ongoing attention to human factors, including the reengineering and business change management work place processes; and

• Involve end users, including physicians, nurses, and administrators, early in the planning process and conceptual design.

FUTURE TRENDS AND DIRECTIONS

Today, a major focus for the province is integrating the provincial telehealth program with other provincial health information initiatives. These include the Electronic Health Record Initiative, the Physician Office Support Program (POSP), and the Pharmacy Information Network (PIN). A second focus is on migrating from the current platforms to a high-speed, high-capacity IP broadband backbone (i.e., the SuperNet project) (Government of Alberta, 2002). In parallel, the province is continuously examining new evolving technologies and partnerships that can optimize the use of ICTs within the health sector, with a focus on quality of care, patient safety, and evidence-based decision making at the point of care.

CONCLUSION

The deployment of the provincial telehealth network continues to grow and to strengthen. Many milestones were encountered in the development of the Alberta Telehealth Network (Table 2). Several significant lessons learned also were documented (Table 3). While significant progress has been made, challenges and impediments remain for the creation of a functional, sustainable, and integrated province-wide telehealth network. Specifically, the successful integration of tele-health into a broad provincial health information and health system demands attention to human, system, and workplace factors. The significance of several critical factors cannot be ignored: different degrees of regional and sectoral readiness to adopt telehealth as well as diversity in selected telehealth priorities, potential cultural shift in the way providers work and learn, training needs, and required public/private/academic sector collaborations.

Table 3. Lessons learned

Business, Funding, fertainafility

• The preparation of ferinorr mfdolr for rh/tod telehealth needs in the Health Regions was helpful to onrero buy-in and progress.

• There is a great deal of work remaining after program initiation.

• Fending opportunities to sfeor the initial and ongoing fporating costs of Telehealth require ongoing eigilanso.

• Accountability for all network sfmpfnontr required articulation.

Policy, Oporatifnal and Infrastructure Issues

• Raising aw/tonorr of tolohoalth and its pftontial continues to be shallonging, as telehealth encompasses a e/tioty of areas and technical complexity, which is difficult to reduce to simple language.

• A number of policy and operational issues around specific applications were identified and required further study and clarification.

• Crfrr-jurirdistifnal policy work is extremely time consuming. For example, the number of editions of the consent policy framework was extremely high.

• Respect for diversity of “state of roadinorr”, prifritior, and partnorr/sfllaffratfrr among Rogifnr was roqeirod.

• A representative governance rtrestero was required. All stakeholders noodod to partisipato in the planning and decision-making during the early stages of rollout.

• A “dosirifn document” for the Minirtor of Health, the Health Authority, the anonymous philanthropic foundation, and the Alberta Medical Association was a tool to enhance successful integration and buy-in.

• A clear understanding of the nature and implications of health reform and restructuring are required before telehealth can be integrated into a regional health system. Telehealth must align with and support major health reform initiatives to continue to be supported by and successful in the provincial funding structure. It must also take into consideration the sfneorgonso of toshnflf-gies as it evolves.

• Alberta Health, the Ministry of Health, was a key player in initial successful implementation.

• Consideration of the province’s overall health inffrmatifn apprfash was important. Multiple reporting requirements are needed.

• In early stages, policy and integration committees were helpful to move agendas along. Commitment was central as expertise, time, as well as expenses were volunteered.

• Continual revisiting of critical issues with RHAs and Provincial Boards, along with ongoing active participation, was required. Perseverance in planning and development is rewarded.

• Adequate infrastructure (telecommunications, trained staff, etc.) for a network was critical.

• Identification of “pressure points,” along with provincial barriers and obstacles was difficult, but essential to move the agenda along.

• Implementation requires close attention to human, system, and workplace factors.

• Ongoing evaluation and monitoring is required for continuous quality improvement.

It also was observed that telehealth and e-health initiatives make substantial impacts in key areas of health reform. Integration requires close attention to the ongoing healthcare restructuring movements as well as to the convergence of technologies. There is a tendency to simply add technology to existing processes; however, some of these processes need to be reengineered in order to realize the full potential of telehealth. Further, changing funding processes to better accommodate telehealth is extremely difficult; the amount and quality of evaluation research on the impact of investments in telehealth must be increased to support the decision makers.

The provincial telehealth network initiative provides ongoing progress reports as health reform and restructuring continue and as integration with other provincial health information initiatives continues.

KEY TERMS

AGNPac: AGNPac is a government of Alberta IP network.

Bandwidth: The range of frequencies trans-mittable through a transmission channel. If the channel is unique, the band is called baseband. If the channel is made multiple through a process of multiplexing, the band becomes wideband and can support data, voice, and video at the same time. (1) The difference between the highest and the lowest frequencies in a data communication channel. (2) The capacity of a channel. (3) A measure of the amount of information and, hence, its transfer speed, which can be carried by a signal. In the digital domain, bandwidth refers to the data rate of the system (e.g., 45 Mbit/sec) (Beolchi, 2003). Bandwidth is a practical limit to the size, cost, and capacity of a telehealth service.

Broadband: A popular way to move large amounts of voice, data, and video. Broadband technology lets different networks coexist on a single piece of heavy- duty wiring. It isolates signal as a radio does; each one vibrates at a different frequency as it moves down the line. Its opposite is baseband, which separates signals by sending them at timed intervals (Beolchi, 2003). Future networks, like those being deployed in Alberta, will carry these higher speed communications (i.e., Broadband ISDN).

E-Health: An emerging field in the intersection of medical informatics, public health, and business, which refers to health services and information delivered or enhanced through the Internet and related technologies. In a broader sense, the term characterizes not only a technical development but also a state of mind, a way of thinking, an attitude, and a commitment for networked, global thinking to improve healthcare locally, regionally, and worldwide by using information and communication technology (Ey-senbach, 2001). The Commission of the European Communities (2004) declares that e-health tools or solutions include products, systems, and services that go beyond simply Internet-based applications and include tools for both health authorities and professionals as well as personalized health systems for patients and citizens.

IP: Internet Protocol is the network layer protocol for the Internet (Beolchi, 2003).

ISDN: Integrated Services Digital Network is a set of international digital telephone switching standards that can be used to transmit voice, data, and video. It offers the advantages of error-free connections, fast call setup times, predictable performance, and faster data transmission than possible when using modems over traditional analogue telephone networks. Basic ISDN services combine voice and data, while broadband services add video and higher-speed data transmission. ISDN offers end-to-end digital connectivity (Beolchi, 2003).

SW56: Switch56 is digital telecommunication that transmits narrow-bandwidth digital data, voice, and video signals.

Telehealth: Encompasses the use of advanced telecommunications technologies to exchange health information and to provide healthcare services across geographic, time, social, and cultural barriers (Reid, 1996). Telehealth refers to all healthcare or social services, preventative or curative, delivered at a distance via a telecommunication, including audiovisual exchanges for information, education and research purposes, as well as the process and exchange of clinical and administrative data (Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services, 2001). Homemade systems or systems used outside of official health information networks are included in the latter definition.