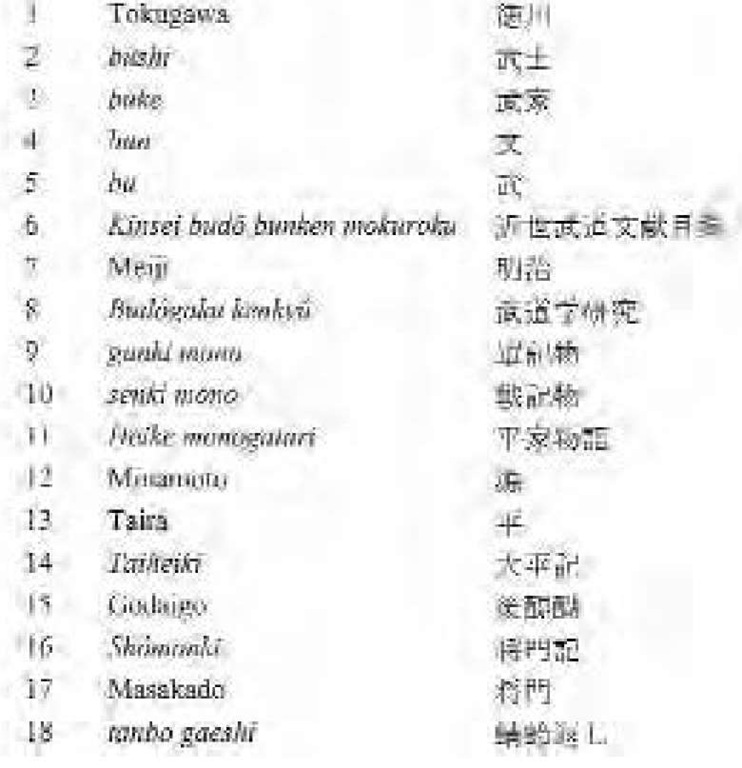

Japanese martial art literature encompasses such a wide variety of genres, both fiction and nonfiction, produced over such a long period of history,that it defies all attempts at simple characterization. The production of martial literature began with early chronicles and anonymous collections of tales concerning wars and warriors and reached its zenith during the Toku-gawa [1] regime (a.d. 1603-1868) when government policies enforced a strict division of social classes, according to which members of the officially designated hereditary class of warriors (bushi [2] or buke [3]) were placed above all other segments of society and charged with administration of government. The Tokugawa combination of more than 250 years of peace, high status afforded to warriors, widespread literacy, and printing technology resulted in the production of vast numbers of texts in which warriors sought to celebrate their heroes, establish universal principles of warfare, record their methods of martial training, adapt arts of war to an age of peace, and resolve the contradiction inherent in government regulations that demanded that they master both civil (bun [4], peaceful) and military (bu [5]) skills. It is this last endeavor more than any other that continues to capture the imagination of modern readers, insofar as Tokugawa warriors applied abstract concepts derived from Chinese cosmology, neo-Confucian metaphysics, Daoist (Taoist) magic, and Buddhist doctrines of consciousness to give new meanings to the physical mediation of concrete martial conflicts.

Some idea of the number of martial art treatises produced by Toku-gawa-period warriors can be gleamed from the Kinsei budo bunken mokuroku [6] (References of Tokugawa-Period Martial Art Texts), which lists more than 15,000 separate titles. This list, moreover, is incomplete, since it includes only titles of treatises found at major library facilities and ignores private manuscripts, scrolls, and initiation documents that were handed down within martial art schools. Following the Meiji [7] Restoration (1868), which marked the beginning both of the end of the hereditary status of warriors and of Japan’s drive toward becoming a modern industrialized state, interest in martial arts immediately declined. Despite a brief resurgence of interest during the militaristic decades of the 1930s and 1940s and the reformulation of certain martial arts (e.g., judo and kendo) into popular competitive sports, relatively few topics about martial arts have appeared since the end of the Tokugawa period. A 1979 References (supplement to Budogaku kenkyu [8], vol. 11, no. 3) of monographs concerning martial arts published since 1868, for example, includes only about 2,000 titles, the vast bulk of which concern modern competitive forms of kendo, judo, and karate. No more than a few Tokugawa-period treatises about martial arts have been reprinted in modern, easily accessible editions. For this reason, knowledge of traditional (i.e., warrior) martial art traditions, practices, and philosophy remains hidden not just from students of modern Japanese martial art sports but also from historians of Japanese education, literature, popular life, and warrior culture.

Early-fourteenth-century scroll fragment depicting the attack of the Kusonoki Masatsuras at the Battle of Rokuhara.

The following survey of Japanese martial art literature, therefore, is of necessity somewhat tentative. It concentrates on works from the Tokugawa period (or before) that have been reprinted and/or influential during modern (i.e., post-1868) times. However influential a work might have been during premodern periods, if it has been ignored by subsequent generations it is omitted here. Even with this limitation, texts from several disparate genres must be surveyed. Through theater, novels, cinema, and television the image of the traditional Japanese warrior (a.k.a. samurai) has attained mythic status (analogous to that of the cowboy or gunfighter of America’s Old West). Insofar as contemporary practitioners and teachers of Japanese martial arts consciously and unconsciously identify themselves with that mythic image, texts depicting legendary warriors and their traits and ethos constitute an indispensable part of Japanese martial art literature. In addition, the texts in which Tokugawa-period warriors analyzed their battlefieldexperiences and systematized their fighting arts remain our best sources for understanding the development and essential characteristics of Japanese martial training. Finally, one cannot fail to mention the early text topics that laid the foundation for the development of the modern competitive forms of martial art that are practiced throughout the world. Thus, our survey covers the following genres: war tales, warrior exploits, military manuals, initiation documents, martial art treatises, and educational works.

War Tales

War tales (gunki mono [9] or senki mono [10]) consist of collections of fictional tales and chronicles about historical wars and warriors. Literary scholars often confine their use of this term to works of the thirteenth through fifteenth centuries, such as Heike monogatari [11] (Tales of the Heike; i.e., the 1180-1185 war between the Minamoto [12] and Taira [13] clans) or Taiheiki [14] (Chronicle of Great Peace; i.e., Godaigo’s [15] 1331-1336 failed revolt against warrior rule), which originally were recited to musical accompaniment and which evolved orally and textually over a long period of time. In a broader sense, however, the term sometimes applies even to earlier battlefield accounts such as Shomonki [16] (Chronicle of Masakado [17]; i.e., his 930s revolt). None of these tales can be read as history. Their authors were neither themselves warriors nor present at the battles they describe. Episodic in nature, they derive dramatic effect primarily from repetition of stereotyped formulas (e.g., stylized descriptions of arms and armor, speeches in which heroes recite their illustrious genealogies, the pathos of death). Overall, they present the rise of warrior power as a sign of the decline of civilization and sympathize with the losers: individuals and families of fleeting power and status who suffer utter destruction as the tide of events turns against them. Thus, Heike monogatari states, in one of the most famous lines of Japanese literature: “The proud do not last forever, but are like dreams of a spring night; the mighty will perish, just like dust before the wind.”

In spite of the fact that war tales are obvious works of fiction, from Tokugawa times down to the present numerous authors have used these works as sources to construct idealistic and romanticized images of traditional Japanese warriors and their ethos. The names of fighting techniques (e.g., tanbo gaeshi [18], dragonfly counter) mentioned therein have been collected in futile attempts to chart the evolution of pre-Tokugawa-period martial arts. Excerpts have been cited out of context to show that medieval warriors exemplified various martial virtues: loyalty, valor, self-discipline, self-sacrifice, and so forth. At the same time, however, these texts also contain numerous counterexamples in which protagonists exemplify the opposite qualities (disloyalty, cowardice). Perhaps because of this very mixture of heroes and villains, these tales continue to entertain and to provide story lines for creative retellings in theater, puppet shows, cinema, television, and cartoons.

Warrior Exploits

Whereas war tales describe the course of military campaigns or the rise and fall of prominent families, tales of warrior exploits focus on the accomplishments of individuals who gained fame for founding new styles (ryuha [19]), for duels, or for feats of daring. The practice of recounting warrior exploits no doubt is as old as the origins of the war tales mentioned above, but credit for the first real attempt to compile historically accurate accounts of the lives and deeds of famous martial artists belongs to Hinatsu Shige-taka’s [20] Honcho bugei shoden [21] (1716; reprinted in Hayakawa et al. 1915). Living in an age of peace when the thought of engaging in life-or-death battles already seemed remote, Hinatsu hoped that his accounts of martial valor would inspire his contemporaries, so that they might emulate the warrior ideals of their forebears. Repeatedly reprinted and copied by subsequent authors, Hinatsu’s work formed the basis for the general public’s understanding of Japanese martial arts down to recent times. Playwrights, authors, and movie directors have mined Hinatsu for the plots of countless swordplay adventures. The most notable of these, perhaps, is the 1953 novel Miyamoto Musashi [22] by Yoshikawa Eiji [23] (1892-1962). This novel (which was translated into English in 1981) more than anything else helped transform the popular image of Miyamoto Musashi (15841645) from that of a brutal killer into one of an enlightened master of self-cultivation. It formed the basis for an Academy Award-winning 1954 movie (released in America as Samurai) directed by Inagaki Hiroshi [24] (1905-1980).

Military Manuals

Japanese martial art traditions developed within the social context of lord-vassal relationships in which the explicit purpose of martial training was for vassals to prepare themselves to participate in military campaigns as directed by their lords. Therefore, instruction in individual fighting skills (e.g., swordsmanship) not infrequently addressed larger military concerns such as organization, command, supply, fortifications, geomancy, strategy, and so forth. Manuals of military science (gungaku [25] or heigaku [26]), likewise, often included detailed information on types of armor, weapons, and the best ways to learn how to use them.

The most widely read and influential military manual was Koyo gunkan [27] (Martial Mirror Used by Warriors of Koshu [28]; reprinted in Isogai and Hattori 1965), published in 1656 by Obata Kagenori [29](1572-1662). Koyo gunkan consists of various texts that purport to record details of the military organization, tactics, training, martial arts, and battles fought by warriors under the command of the celebrated warlord Takeda Shingen [30] (1521-1573). Although ascribed to one of Takeda’s senior advisers, Kosaka Danjo Nobumasa [31] (d. 1578), it was probably compiled long after its principal characters had died, since it contains numerous historical inaccuracies, including fictional battles and imaginary personages (e.g., the infamous Yamamoto Kanzuke [32]). In spite of its inaccuracies, Koyo gunkan has been treasured down to the present for its rich evocation of the axioms, motivational techniques, and personal relations of late sixteenth-century fighting men.

Yamaga Soko [33] (1632-1685) was the most celebrated instructor of military science during the Tokugawa period. Yamaga combined military science (which he studied under Obata Kagenori) with Confucianism and Ancient Learning (kogaku [34]) to situate military rule within a larger social and ethical framework. His Bukyo shogaku [35] (Primary Learning in the Warrior Creed, 1658; reprinted 1917) formulated what was to become the standard Tokugawa-period justification for the existence of the hereditary warrior class and their status as rulers: Warriors serve all classes of people because they achieve not just military proficiency but also self-cultivation, duty, regulation of the state, and pacification of the realm. Through his influence, martial art training came to be interpreted as a means by which warriors could internalize the fundamental principles that should be employed in managing the great affairs of state.

Initiation Documents

Before Meiji (1868), martial art skills usually were acquired by training under an instructor who taught a private tradition or style (ryuha [36]) that was handed down in secret from father to son or from master to disciple. There were hundreds of such styles, and most of them gave birth to new styles in endless permutations. This multiplication of martial traditions occurred because of government regulations designed to prevent warriors from forming centralized teaching networks across administrative borders. Ryuha, the Japanese term commonly used to designate these martial art styles, denotes a stream or current branching out from generation to generation. By definition, though not necessarily so in practice, each style possesses its own unique techniques and teachings (ryugi [37]), which are conveyed through its own unique curriculum of pattern practice (kata [38]). Typically, each style bestowed a wide variety of secret initiation documents (densho [39]) on students who mastered its teachings. Although some martial art styles still guard their secrets, today hundreds of initiation documents from many different styles have become available to scholars. Manyof them have been published (see reprints in Imamura 1982, etc.; Sasamori 1965). These documents provide the most detailed and the most difficult to understand accounts of traditional Japanese martial arts.

Martial art initiation documents vary greatly from style to style, from generation to generation within the same style, and sometimes even from student to student within the same generation. They were composed in every format: single sheets of paper (kirikami [40]), scrolls (makimono [41]), and bound volumes (sasshi [42]). There were no standards. Nonetheless, certain patterns reappear. Students usually began their training by signing pledges (kishomon [43]) of obedience, secrecy, and good behavior. Extant martial art pledges, such as the ones signed by Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu [44] (1542-1616), provide invaluable historical data about the relationships between martial art styles and political alliances. As students proceeded through their course of training they received a series of written initiations. These writings might have consisted of curriculums (mokuroku [45]), genealogies (keifu [46]), songs and poetry of the way (doka [47]), teachings adapted from other styles (to no mono [48]), lists of moral axioms and daily cautions (kokoroe [49]), diplomas (menjo [50]), and treatises. In many styles the documents were awarded in a predetermined sequence, such as initial, middle, deep, and full initiation (shoden [51], chuden [52], okuden [53], and kaiden [54]).

A key characteristic of initiation documents, regardless of style, is that they were bestowed only on advanced students who had already mastered the techniques, vocabulary, and concepts mentioned therein. For this reason they typically recorded reminders rather than instructions. Sometimes they contained little more than a list of terms, without any commentary whatsoever. Or, perhaps the only comment was the word kuden [55] (oral initiation), which meant that the student must learn this teaching directly from the teacher. Many initiation documents use vocabulary borrowed from Buddhism but with denotations completely unrelated to any Buddhist doctrines or practices. Moreover, initiation documents from different styles sometimes used identical terminology to convey unrelated meanings or to refer to dissimilar technical applications. For this reason, initiation documents cannot be understood by anyone who has not been trained by a living teacher of that same style. Recently, however, it has been demonstrated that the comparative study of initiation documents from a variety of styles can reveal previously unsuspected relationships among geographically and historically separated traditions.

Martial Art Treatises

Systematic expositions of a particular style’s curriculum or of the general principles of martial performance also were produced in great numbers.

The earliest extant martial art treatises are Heiho kadensho [56] (Our Family’s Tradition of Swordsmanship, 1632) by Yagyu Munenori [57] (15711646) and Gorin no sho [58] (Five Elemental Spheres, 1643) by Miyamoto Musashi (both reprinted in Watanabe et al. 1972). Both texts were written by elderly men who in the final years of their lives sought to present their disciples with a concluding summation of their teachings. Until modern times both texts were secret initiation documents. Like other initiation documents they contain vocabulary that cannot be fathomed by outsiders who lack training in their respective martial styles. For this reason, the modern interpretations and translations that have appeared thus far in publications intended for a general audience have failed to do them justice. In some cases, the specialized martial art terminology in these works has been interpreted and translated into English in the most fanciful ways (e.g., Suzuki 1959).

Heiho kadensho begins by listing the elements (i.e., names of kata) in the martial art curriculum that Munenori had learned from his father. This list is followed by a random collection of short essays in which Munenori records his own insights into the meaning of old sayings or concepts that are applicable to martial art training. In this section he cites the teachings of the Zen monk Takuan Soho [59] (1573-1643), Chinese military manuals, neo-Confucian tenets, and doctrines of the Konparu [60] school of No [61] theater. Munenori asserts that real martial art is not about personal duels, but rather lies in establishing peace and preventing war by serving one’s lord and protecting him from self-serving advisers. He emphasizes that one must practice neo-Confucian investigation of things (kakubutsu [62]; in Chinese, gewu) and that for success in any aspect of life, and especially in martial arts, one must maintain an everyday state of mind (byojoshin [63]).

Gorin no sho eschews the philosophical reflection found in Heiho kadensho and concentrates almost exclusively on fighting techniques. It basically expands Musashi’s earlier Heiho sanjugoka jo [64] (Thirty-Five Initiations into Swordsmanship, 1640; reprinted in Watanabe et al. 1972) by organizing his teachings into five sections according to the Buddhist scheme of five elements: Earth concerns key points for studying swordsmanship; Water concerns Musashi’s sword techniques; Fire concerns battlefield techniques; Wind concerns the techniques of other styles; and Space (i.e., emptiness) encourages his disciples to avoid delusion by perfecting their skills, tempering their spirits, and developing insight. Throughout the work, Musashi’s style is terse to the point of incomprehensibility. In spite of his use of the elemental scheme to give his work some semblance of structure, the individual sections lack any internal organization whatsoever. Some assertions reappear in several different contexts without adding any new information. Much of what can be understood appears self-contradictory. This unintelligibility, however, allows the text to function as Rorschachinkblots within which modern readers (businessmen, perhaps) can discover many possible meanings.

Many other formerly secret martial art treatises have commanded the attention of modern readers. Kotoda Toshisada’s [65] Ittosai sensei kenpo sho [66] (Master Ittosai’s Swordsmanship, 1664; reprinted in Hayakawa et al. 1915) uses neo-Confucian concepts to explain doctrines of Itto-ryu [67], a style that greatly influenced modern kendo. Mansenshukai [68] (All Rivers Gather in the Sea; reprinted in Imamura 1982, vol. 5) is an topic of espionage (ninjutsu [69]) techniques. Shibugawa Tokifusa’s [70] Jujutsu taiseiroku [71] (Perfecting Flexibility Skills, 1770s; reprinted in Imamura 1982, vol. 6) explains the essence of Shibugawa-ryu Jujutsu [72] so well that it is still studied by students of modern judo. Sekiunryu kenjutsu sho [73] (a.k.a. Kenpo Seikun sensei soden [74]; reprinted in Watanabe 1979) by Kodegiri Ichiun [75] (1630-1706) has garnered attention for its sharp criticism of traditional swordsmanship as a beastly practice and its assertion that the highest martial art avoids harm both to self and to one’s opponent.

Not all martial art treatises were kept secret. Many were published during the Tokugawa period. Not surprisingly, these are the ones that modern readers can understand with the least difficulty. Tengu geijutsuron [76] (Performance Theory of the Mountain Demons; reprinted in Hayakawa et al. 1915) and Neko no myojutsu [77] (Marvelous Skill of Cats; reprinted in Watanabe 1979) both appeared in print in 1727 as part of Inaka Soji [78] (Countrified Zhuangzi) by Issai Chozan [79] (1659-1741). Likening himself to the legendary Chinese sage Zhuangzi, Issai explains swordsmanship in Confucian terms in Tengu geijutsuron and in Daoist (Taoist) terms in Neko no myojutsu. Both works were enormously popular and saw many reprints. Hirase Mitsuo’s [80] Shagaku yoroku [81] (Essentials for Studying Archery; published 1788; reprinted in Watanabe 1979) provides an invaluable overview of how archery evolved during the eighteenth century. Hirase asserts that archery is the martial art par excellence and laments that contemporary archers have forgotten its true forms, which he then proceeds to explain. Similar works were published regarding other forms of martial training: gunnery, horsemanship, pole-arms, and so forth.

The most influential treatise was not written by a warrior, but by a Buddhist monk. It consists of the instructions that Takuan Soho presented to Yagyu Munenori regarding the way the mental freedom attained through Buddhist training can help one to better master swordsmanship and to better serve one’s lord. First published in 1779 as Fudochi shin-myoroku [82] (Marvelous Power of Immovable Wisdom; reprinted in Hayakawa et al. 1915), Takuan’s treatise has been reprinted countless times ever since and has reached an audience far beyond the usual martial art circles. Takuan emphasized the importance of cultivating a strong senseof imperturbability, the immovable wisdom that allows the mind to move freely, with spontaneity and flexibility, even in the face of fear, intimidation, or temptation. For Takuan the realization of true freedom must be anchored to firm moral righteousness. He likened this attainment to a well-trained cat that can be released to roam freely only after it no longer needs to be restrained by a leash in order to prevent it from attacking songbirds. Under the influence of the extreme militarism of the 1930s and 1940s, however, the freedom advocated by Takuan was interpreted in amoral, an-tinomian terms, as condoning killing without thought or remorse. For this reason it has been condemned by recent social critics for contributing to the commission of wartime crimes and atrocities.

Educational Works

In 1872, the new Meiji government established a nationwide system of compulsory public education. That same year, the ministry in charge of schools promulgated a single nationwide curriculum that included courses in hygiene and physical exercise. In developing these courses, Japanese educators translated a great number of text topics and manuals from European countries, which only a few decades earlier had developed the then-novel practices of citizen armies, military gymnastics, schoolyard drills, and organized athletic games. Tsuboi Gendo [83] (1852-1922) was the first person to attempt to introduce to a general Japanese audience the notion that exercise could be a form of recreation and a pleasant way to attain strength and health, to develop team spirit, and to find joy simply in trying to do one’s best. His Togai yuge ho [84] (Methods of Outdoor Recreation, 1884) helped ordinary Japanese accept the concepts of sport and, more importantly, sportsmanship.

In the eyes of many Japanese educators, a huge gulf separated traditional martial arts from sports and sportsmanship. The Ministry of Education, for example, initially rejected swordsmanship (kenjutsu [85]) and jujutsu instruction at public schools. Its evaluation of martial art curricu-lums (“Bugika no keikyo” [86], Monbusho 1890) found martial arts to be deficient physically because they fail to develop all muscle groups equally and because they are dangerous in that a stronger student can easily apply too much force to a weaker student. They are deficient spiritually because they promote violence and emphasize winning at all costs, even to the point of encouraging students to resort to trickery. In addition, they are deficient pedagogically because they require individual instruction, they cannot be taught as a group activity, they require too large a training area, and they require special uniforms and equipment that students cannot keep hygienic. At the same time that the Ministry of Education was rejecting traditional Japanese martial arts, however, it sought other means to actively promotethe development of a strong military (kyohei [87]). In 1891, it ordered compulsory training in European-style military calisthenics (heishiki taiso [88]) at all elementary and middle schools. The ministry stated that physically these exercises would promote health and balanced muscular development, spiritually they would promote cheerfulness and fortitude, and socially they would teach obedience to commands.

Faced with this situation, many martial art enthusiasts sought to reform their training methods to meet the new educational standards and policies. In particular, they developed methods of group instruction, exercises for balanced physical development, principles of hygiene, rules barring illegal techniques, referees to enforce rules, tournament procedures that would ensure the safety of weaker contestants, and an ethos of sportsmanship. Kano Jigoro [89] (1860-1938), the founder of the Kodokan [90] style of jujutsu (judo), exerted enormous influence on all these efforts in his roles as president (for twenty-seven years) of Tokyo Teacher’s School (shi-han gakko [91]), as the first president of the Japanese Physical Education Association, and as Japan’s first representative to the International Olympic Committee. Under Kano’s leadership, Tokyo Teacher’s School became the first government institution of higher education to train instructors of martial arts. Kano was a prolific writer. His collected works (three volumes, 1992) provide extraordinarily rich information on the development of Japanese public education, judo, and international sports.

Kano also encouraged others to write modern martial art text topics, several of which are still used today. Judo kyohan [92] (Judo Teaching Manual, 1908; reprinted in Watanabe 1971) by two of Kano’s students, Yokoyama Sakujiro [93] (1863-1912) and Oshima Eisuke [94], was translated into English in 1915. Takano Sasaburo [95] (1863-1950), an instructor at Tokyo Teacher’s School, wrote a series of works, Kendo [96] (1915; reprinted 1984), Nihon kendo kyohan [97] (Japanese Kendo Teaching Manual, 1920), and Kendo kyohan [98] (Kendo Teaching Manual, 1930; reprinted 1993), that helped transform rough-and-tumble gekken [99] (battling swords) into a modern sport with systematic teaching methods and clear standards for judging tournaments. These authors (as well as pressure from nationalist politicians) prompted the Ministry of Education to adopt jujutsu and gekken as part of the standard school curriculum in 1912 and to change their names to judo and kendo, respectively, in 1926. Finally, Kano was instrumental in helping Funakoshi [100] Gichin [101] (1870-1956) introduce Okinawan boxing (karate) to Japan (from whence it spread to the rest of the world). Funakoshi’s Karatedo kyohan [102] (Karate Teaching Manual, 1935; English translation 1973) remains the standard introduction to this martial art.

![tmp32-1_thumb[1] tmp32-1_thumb[1]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/_1wtadqGaaPs/THerlSVmB-I/AAAAAAAAWfQ/7OWz-PepWsM/tmp321_thumb1_thumb1.jpg?imgmax=800)

![tmp32-2_thumb[1] tmp32-2_thumb[1]](http://lh4.ggpht.com/_1wtadqGaaPs/THersXH_ibI/AAAAAAAAWfY/UQ8Hk9RgbWs/tmp322_thumb1_thumb1.jpg?imgmax=800)

![tmp32-3_thumb[2] tmp32-3_thumb[2]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/_1wtadqGaaPs/THerwGnfepI/AAAAAAAAWfg/hng14eNM0Tw/tmp323_thumb2_thumb.jpg?imgmax=800)