During the early 1900s, feminists often regarded combative sports such as boxing, wrestling, fencing, and judo as tools of women’s liberation. Because these sports were historically associated with prizefighting (in Shakespeare’s time, prizefighters were fencers rather than pugilists) and saloons (the Police Gazette was holding “Female Championships of the World” in New York City saloons as early as 1884), the middle classes publicly despised such activities.

Nevertheless, around 1900, combative sports started becoming more fashionable. Fencing was particularly popular with women, partly because of its exercise value, partly because it was said to build character, and mostly because it was not a contact sport.

During the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, judo classes became popular with upper-class women. Partly this was due to the Japanese army claiming that judo was the secret weapon that made its soldiers invincible in the trench fighting around Port Arthur, and partly it was due to the exaggerated claims of jujutsu teachers and sportswriters. For example, in The Cosmopolitan of May 1905, a Japanese visitor to New York named Kat-sukuma Higashi boasted that given six months, he could teach any 110-pounder of good moral character to “meet a man of twice his weight and three times his muscular strength and overcome him under all circumstances.” This was hyperbole rather than fact—within the year the 120-pound Higashi himself proved incapable of beating either a 140-pound professional wrestler, George Bothner, or a 105-pound judoka (judo player), Yukio Tani. Nevertheless the myth persists. Witness, for example, the enormous popularity of The Karate Kid, a Hollywood film that saw its youthful hero change from chump to champ during the seven weeks between Halloween and Christmas.

Jujutsu was first introduced to England in March 1892. The occasion was a lecture given by T. Shidachi, secretary of the Bank of Japan’s London branch, and his assistant Daigoro Goh (Smith 1958, 47-62). Seven years later, Yukio Tani introduced jujutsu into British music halls, and by the time “The Adventure of the Empty House” appeared in Strand Magazine in October 1903, Sherlock Holmes was using a Japanese-based system of wrestling called baritsu to free himself from the clutches of Professor Mo-riarty. From the 1890s there were also judo and jujutsu practitioners in the United States, several of whom, like Tani, worked as professional wrestlers.

Seattle police officer Sven J. Jorgensen teaches Florence Clark jujutsu, July 10, 1928.

Proponents of the art suggested from the first that judo would be useful for women. One early topic advocating this was A. Cherpillod’s Meine Selbsthilfe Jiu Jitsu fur Damen (My Self-Help Jiu Jitsu for Ladies) (Nurem-burg: Attinger, 1901). Another was Irving Hancock’s Physical Training for Women by Japanese Methods (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904). And two years later, Physical Training for Women was followed by The Fine Art of Jujutsu by Mrs. Roger (Emily) Watts (London: Heinemann, 1906).

Male reactions to women’s involvement in such activities varied. A few men thought it wonderful, Sam Hill of Seattle even suggesting that all white women living in the South learn jujutsu for self-defense. Others were appalled, seeing it as contrary to God’s will. Most, however, were simply amused until, during the late 1930s, women’s self-defense was made acceptable by militarization.

Women’s reactions varied, too. Suffragettes and rich women often viewed participation in combative sports as empowering. Working-class women sometimes viewed them as a means toward getting a paying job in vaudeville. Working women and actresses also thought that some method of physical retaliation useful against men who reached under their skirts was handy. On the other hand, many parents had strong misgivings regarding all female athletics. The fear seems to have been that “respectable” boys would not marry girls who could beat them at anything.

Women boxers in Washington, ca. 1970.

But whether mothers and educators liked it or not, by the 1920s huge numbers of young women were regularly playing baseball, basketball, golf, tennis, and volleyball. Unable to stem the tide, the educators and physicians sought to turn it by stating that, although nothing preserved female beauty so well as sport, there were certain sports that were better than others and a few (including soccer and boxing) that were downright unladylike. Furthermore, competition and the development of unsightly muscles could be minimized by new rules that made girls’ sports considerably less exciting than boys’ sports.

These rules could be draconian. In 1922, for example, rules for a girl’s basketball team at Martinez High School in San Francisco included the following: “No dancing, no soup, no milk, no candy, no ice cream; [hot] chocolate while resting instead of oranges; two hours rest before each game; eight hours sleep daily; no fried foods; no pastry; feet to be bathed three times weekly in tannic acid” (Japan Times, March 29, 1922). Others were simply inane, such as those requiring girls to essentially stand in one place while playing basketball. Although the athletes protested (the Martinez girls, for instance, said no dancing, no basketball team), hardly anyone, least of all physical education teachers or school administrators, listened.

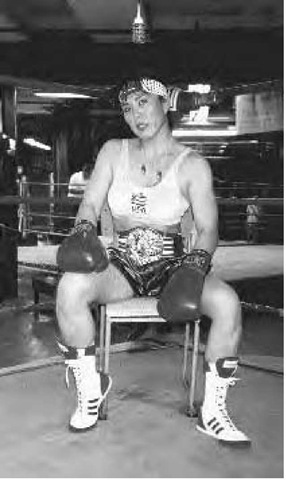

Tamami “Sky” Hosoya, USA Boxing Women’s national champion (1997) and professional wrestler.

In the words of a Scientific American author in 1936, “Feminine muscular development interferes with motherhood” (Laird 1936).

Despite some loosening of dress codes during the Edwardian era, before World War I most female athletes dressed as conservatively as Iranian female athletes of the 1990s. Afterwards, however, dress codes relaxed, and newspapers started showing pictures of attractive movie starlets dressed in bathing suits. As a result, by the 1930s female athletic attire roughly matched equivalent male attire except in “genteel” sports such as fencing and golf, where skirts remained the norm into the 1950s. Still, Mrs. Grundies worried about “indecent exposure,” and as a result various elastic undergarments were developed. During the 1910s, for example, some women tried Leo McLaglan’s “Jujutsu Corset,” and during the 1950s female professional wrestlers supported their rhinestone-encrusted bathing suits with 2-inch-wide elastic bands. The most popular device, however, was the brassiere. First developed by the New York socialite Mary Phelps Jacobs around 1914, its original purpose was not to assist in athletics but to flatten the bust.

Even allowing for hype—vaudevillians and society women both received more than their fair share of media coverage—early twentieth-century women played combative sports for the same reasons as their granddaughters. In short, they did them for one of four main reasons: body sculpting, socializing with friends or business acquaintances, personal empowerment, or physical self-defense.

Another constant over time was the derisive attitude that people— women as well as men—took toward female participation in “unladylike” sports. For example, as recently as 1981, some sociologists in the United States wrote about female karate black belts:

There was evidence that a psychology of tokenism is operating in Karate as it operates in other domains. The skills of these “tokens” are belittled, and ritualized deference is withheld. The interesting question is whether increasing participation and success by women will eliminate the token aspects of responses to them. Or will the cognitive inconsistency be resolved by devaluing the achievement of a black belt (a pattern found in the occupational world). The long-term results are interesting because the issues involved are so fundamental to the ideology of gender typing. (Smith et al. 1981, 20)

Sexual stereotyping—”any woman who boxes must be a lesbian”— was another constant. As recently as May 1994, the Irish boxer Deirdre Gogarty told British video journalists, “I’m always afraid people think I’m butch. That’s my main fear. I used to hang a punch bag in the cupboard and bang away at it when no-one was around, so nobody would know I was doing it. I was afraid people would think me weird and unfeminine” (quoted in Hargreaves 1996, 130).

Still, resistance toward female involvement in combative sports seems to have softened somewhat over the years, especially when the female involvement is amateur rather than professional. Said the father of Dallas Malloy, a 16-year-old amateur boxer profiled in the Sunday supplement of the Seattle Times on August 8, 1993, “We’ve tried to encourage our daughters to do something interesting with their lives, not be a sheep. I have a feeling whatever Dallas does, she will always be different. She’ll do anything but what the crowd does.”