The use of a stick, club, or staff as a weapon in combat or in combative sports is called stickfighting. Today these uses can be classed into two types. First, there are those arts that developed for use with a stick, such as mak-ila in the Basque highlands, shillelagh in Ireland, quarterstaff in Europe, and bojutsu in Okinawa. Second, there are those arts that developed from the use of another weapon like the sword or spear. These arts would include la canne d’armes in France, singlestick in England, and arnis de mano in the Philippines. To say the use of the stick in fighting is one of man’s earliest weapons is a relatively obvious statement supported by archaeology. A broken branch, an antler, or a large leg bone makes an excellent impromptu club. Stickfighting systems have developed around the world and many survive today in the forms of sports, folk dances, and cultural activities as well as fighting systems. Many others systems did not survive the introduction of reliable, personal firearms and sport forms of fencing.

At one time, each country in Europe seems to have had its own system of stickfighting. Fighting with sticks or cudgels was accepted for judicial duels in medieval Europe, and several records of these fights survive. In the fifteenth century, Olivier de la Marche told of a judicial duel between two tailors fought with shield and cudgel. According to ancient custom in Burgundy, the burghers of Valenciennes were allowed to participate in a judicial combat with cudgels. These civilians of the middle class had their shield reversed (upside down), as they were commoners and hence not allowed to use a knightly shield. The loser was then taken and hanged upon a gibbet immediately outside the lists. Other judicial combats with clubs are reported in England, Germany, and France. In Shakespeare’s King Henry VI, Part 2, a trial by combat between a master and his apprentice with cudgels is based on a historical case (act 2, scene 3). In Ireland, the use of the walking stick, the shillelagh, and the staff were common, as the British occupiers restricted access of the population to weapons. The association of the shillelagh with the Irish in the United States is so strong that the shillelagh has become one of the symbols of St. Patrick’s Day. Several other weapons were used, and there are some attempts to preserve or recreate these systems under the name of brata (stick). The United Kingdom had several native systems, associated not only with the Welsh, the Scottish, and the English in general but also with local regions. By the nineteenth century, two systems seem to predominate: the quarterstaff and the singlestick. Quarterstaff, a 6-foot stave about 1 1/4 to 1 1/2 inches in diameter, goes back to earliest times. Mentioned in the stories of Saxons and Vikings, it became the preferred weapon of the yeoman or peasant. It is mentioned in George Silver’s Paradoxes of Defense, and in the late 1600s, a British sailor defeated three opponents armed with rapiers in a bout before a Spanish court. It was played as a sport by the British military up into the twentieth century and was taught to the Boy Scouts in the United Kingdom and United States up until the late 1960s. Quarterstaff techniques were taught to the police in the United Kingdom, the United States, and India for use with riot batons, and the lathi, an Indian police staff about 5 feet long, shows considerable influence from it. Currently, it is still used for military training, and several groups are preserving or recovering it, along with other English martial arts.

Cudgel or singlestick was originally used to train soldier in sword technique, but later became its own martial art. Civilians played it as a sport and as a method of defending oneself with a cane. As a rough sport, it was taught and played in colleges, schools, and county fairs. Cudgel play was a distinct descendant of the short-sword and dagger play of Silver’s time, which gladiators of James Miller’s and James Figg’s day still recognized. Miller, himself a noted Master of Defence, published a topic in 1737 with plates detailing the weapons of the craft, including the cudgel. James Figg was considered the greatest Master of Defence and a well-known teacher in the same period. As the use of the traditional weapons had faded from the battlefield, the masters earned money by having exhibitions and public matches like the gladiators of old. Those professionals fought some of their duels on the stage with a Scottish broadsword in the right hand, and in the left a shorter weapon, some 14 inches in length, furnished with a basket hilt similar to that of their swords, which they used in parrying. The cudgel players copied these weapons in a less dangerous form, the steel blades being replaced by an ash stick about a yard in length and as thick as a man’s middle finger, with hilts (known by the name of pots), usually made of wickerwork or leather. Cudgel players were often used to warm up the audience for the main event. The original purpose appeared to have been training for use of the backsword.

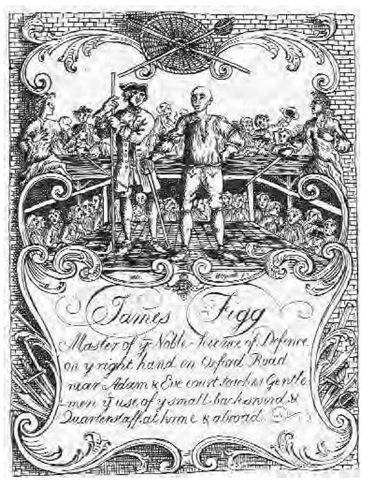

James Figg teaches men the art of self-defense with the use of a backsword and quarterstaff in a trade card engraving by William Hogarth.

Singlestick was simply the use of the one larger stick instead of two. To prevent any unfair use of the left hand, that hand was tied in various fashions, according to the local rules. The men, when engaged, stood within striking distance, the legs being kept straight or nearly so. Cuts and thrusts were performed as with the saber or backsword. There was no lunging in the earlier forms, but thrusts were allowed, and later texts mention the lunge as acceptable. A considerable amount of movement of the feet and body was permitted, and overall several similarities are seen with the German fraternity sport of schlager. Several fictional characters, such as Sherlock Holmes and Tom Brown, were skilled at it. Under some rules, bouts continued until one participant was bleeding from the head an inch above the eyes. Schools that taught to more genteel customers, such as An-gelo’s school in the 1750s in London, used leather jackets and cagelike headgear. Singlestick was taught in the military and police as a way of training for both the sword and nightstick. Spread throughout the British Empire, it appears to have influenced the Sikh art of gatka, in which the basic practice sword and its cuts closely resemble those of singlestick. In England, it was played in private schools until the 1930s. Attempts to revive singlestick with the use of padded jackets and fencing masks for increased protection are ongoing today.

Eire was also a center of stickfighting, and the best-documented style is that of the faction fighters of the nineteenth century. Irish stickfighting used either a single long stick of walking-stick length called the bata or a pair, with a shorter stick carried in the off hand. This short stick is what became associated with the Irish in the United States as the shillelagh. The term actually was used for a grade of oak exported to Europe. The longer stick was held in the middle, similarly to the coulesse (involving changing the striking end of the baton) techniques of baton (walking staff) in savate, so that the lower half lay along and protected the forearm. Strikes were done with the head of the stick. When used, the shorter stick served to block, as in the cudgel play described above. Techniques for longer staves (called wattles) and cudgels are also known to have existed. Fighting took place almost everywhere, and men trained from youth in the use of the stick, with each faction having its own fencing master. Faction fights took place with up to a thousand men participating, and ritual challenges existed. Fights occurred at wakes, county fairs, and dances, as well as by arrangement. The women joined in, not with sticks, but with a rock in a sock or scarf. Needless to say, the authorities did not at all approve of these fights. Fights were often not deadly duels, but they were looked on as a rough but good-natured contest of skill. G. K. Chesterton, writing while memories of the faction fights were still fresh, said: “If you ever go to Ireland, you will find it truly said, that it is the land of broken hearts and the land of broken heads” (1980, 261).

The Scandinavian countries also had various styles using the walking stick and the quarterstaff. One still exists today called Stav (staff) that claims a 1,500-year descent in a familial line. In addition to stickfighting, this system includes training in the use of the sword and the ax. Many systems existed in the Germanic and central European lands. Of these, two German stickfighting styles, stochfechten (stickfighting) and Jaegerstocken (hunting or walking stick), appear to have survived to today. In addition, a wooden practice sword called the dusack was a popular weapon among the tradesmen in the later Middle Ages. Records of stickfighting techniques are found in the sword-fighting manuals of Europe, in which a stick or short staff (about three to five feet in length) is shown used against a sword. In addition, many swordsmen used wands to train with more safely, so it is easy to see how sword techniques would become intertwined with stick techniques. In the Netherlands, cane and cudgel systems existed similar to la canne et baton of today. The Bretons developed a stickfighting art that uses a 3-foot stick that is forked or hooked on the top like a cane. It appears to be associated with Lutte Breton (Breton wrestling), and the hooked end is used to trip or trap an opponent. The Basques have systems for using the makila (a walking stick that separates into two equal pieces with a small blade concealed inside one side) as well as the shepherd’s crook, a light 5-foot stick. Both are used in zipota (Basque; kickfighting) as well as folk dance. Tribal leaders also carried the makila as a sign of authority. Spain had similar arts, mainly performed today as folk dance. These appear to be closely related to the canne et baton of savate. One order of Spanish knights (The Order of the Band) were required to play at wands six times a year to maintain their status. Undoubtedly, the art was familiar to Spanish soldiers in the Philippines, which allowed the rapid assimilation of Spanish techniques into the local arts of kali or arnis along with the techniques of espada y daga (sword and dagger). A local fencing teacher in Maryland, now in his seventies or eighties, taught the sword-and-dagger techniques he learned along with the modern fencing weapons as a child in the Philippines as a son of a member of the American forces. In Portugal, the art of jogo do pau still exists as self-defense, cultural tradition, and sport.

France has the most organized and widely practiced form of stick-fighting in Europe: the fighting art of la canne d’armes and its sport form, la canne de combat. These are closely associated with savate. Stickfighting techniques have been part of savate since its codification by Michel Casseux in 1803. He listed fifteen kicking and fifteen cane techniques. Danse de rue Savate (Dance of Savate Street) actually has several types of stickfighting systems: la canne d’armes, using a cane or dress walking stick; its sport form of canne de combat, using a baton (a 65-inch walking staff); and the stickfighting system of Lutte Parisienne (Parisian Wrestling), using a crooked cane. La canne d’armes is the street combat system that developed with the cane during a ban of carrying swords within the city limits of Paris under the Napoleonic laws. The cane is handled much like a sword, and many fencers took to practicing it as a legal alternative to the sword. This crossover of practitioners led to the introduction of many court and small-sword techniques into la canne. The sport form, la canne de combat, utilizes a limited set of six techniques. These six cuts are called brisse (overhead), crosse brisse (backhand overhead), lateral (side), crosse lateral (backhand side), enleve (uppercut), and crosse enleve (backhand up-percut). Thrusts and the other cuts are banned as too dangerous. The cuts must be chambered (hand “cocked”) behind the shoulder, and the legal targets are the lower leg, the body, and the head. A padded suit and headgear are worn. Bouts consist of four two-minute rounds. The sport is regulated in France by the Comite National de Canne de Combat et Baton and in the United States by the USA Savate and Canne de Combat Association, which is part of the International Guild of Danse de Rue Savate. The baton is a 64-inch staff that developed from the walking stick and a sign of authority carried by certain officers and nobles in France. The art of using it was taught to cavalrymen as a method of defending oneself with the lance when on foot and appears to have developed from pole-arms. It is sometimes erroneously referred to as grand baton or moutinet. Unlike the quarterstaff, the baton is held so the thumbs of both hands face each other (the lead hand is pronated). Finally, the crooked cane is also taught. Coming from Lutte Parisienne, this is an impact weapon whose hooked end can be used to trap, to tear, or to trip.

In Russia, stickfighting is called shtyk and uses a 5-foot stick called the polka. One of the stories of the origin of shtyk attributes it to the pre-Christian priests of the thunder god Perun. It is closely associated with the use of the pike, one of the big four of Russian medieval weapons (sword, ax, pike, and war-hammer). The emphasis in both shtyk and Russian pike fighting was the unbalancing of the opponent. As the arts were designed for mass combat, the ideal was to overturn an opponent, creating an opening in his line and leaving him for one’s comrades to finish off. This emphasis on overturning is also seen in individual combat, in which to overturn or unbalance an opponent without injury is considered a sign of high skill. Later these same techniques were adapted to the bayonet. Shtyk is closely associated with the Golitsin family, which was one of the branches of the royal family before the Russian Revolution. Movements with the polka include swinging and thrusts, but more emphasis is placed on levering and screwing (a twisting type of thrust). Parries are ideally stringering, a kind of sticky contact in which you keep control of the opponent’s weapon. The Russian Martial Arts Federation (ROSS) is currently sponsoring the development of a sport form of the art.

In Upper Egypt (actually the highlands to the south), there is a centuries-old martial art system using stick and swords, called tahteeb. In fact, it can be traced to the time of the Pharaoh, as drawings on the walls of the ancient tombs of kings from that era show figures practicing the art using kendo-style postures. Nowadays, members of the Ikhwaan-al-Muslimeen (Muslim Brotherhood) practice it at their religious schools. Another style using a longer walking staff is found among the Bedouin and is called naboud. Other Middle Eastern, Arabic, and North African countries appear to have had similar stickfighting systems, which were normally derived from the sword.

In North and South America, the majority of stickfighting systems are imported forms or variations thereon. The original native tribes used various wooden clubs and swords in combat, but little or nothing is known about systematic approaches to training. In North America today, the closest thing to a national system is the collection of techniques of police and military baton use. This appears to be developed from singlestick, quarter-staff, and la canne. Recently, tremendous influence from arnis, kali, and jo (Japanese; staff, which is approximately 4 feet long) techniques can be seen. Certain ethnic groups have preserved, to a greater or lesser extent, the stickfighting arts of their homeland. The Basques in South Texas and Idaho still retain the makila and shepherd’s staff, at least in dance. The Ukrainians in western Canada preserve some stick techniques in folk dance, as do Russian groups across the United States. The Quebecois have traces of la canne, and Czech settlers in the Midwest and central Texas retained parts of Sokol (falcon, the wrestling and physical training of Czechs, as well as the name of their social hall) in their gymnasiums. However, most of these remnants are of limited influence and are fading as the children become more Americanized. The most popular stickfighting arts appear to be the arnis or kali systems from the Philippines and the staff techniques from aikido. Recent attempts to reintroduce la canne de combat are still limited in scope, and quarterstaff and singlestick, despite their importation with the Boy Scouts, are mainly extinct.

In South America and the Caribbean, the picture is brighter. Several Caribbean nations have stickfighting associated with the festival of Carnival (just before the start of Lent). Trinidad and Tobago actually advertises that stickfighting competitions are held during Carnival. The stick-fighting appears to be based on quarterstaff and baton techniques using the pronated grip. Interestingly, associated with the stickfighting is the use of the whip by pierrots (clowns), paralleling the association of la canne et baton with le fouet (the whip) seen in savate. Bois (wood) is practiced in what were once the French colonies in the Caribbean and appears to be la canne blended with African traditions. In South America, capoeira has maculele, a dance form and style of fighting that uses sticks called grimas, which looks very much like the Basque folk dances using the makila. The sticks are used in place of machetes to reduce risk and hide the skill from the authorities, and the local machete fighting style is known by the same name.