This pedagogical device, best known by its Japanese name, kata ([1]; pronounced hyung in Korean, xing in Mandarin), represents the central methodology for teaching and learning the body of knowledge that constitutes a traditional school or system of martial art throughout much of East Asia. The standard English translation for kata is “form” or “forms,” but while this may be linguistically accurate, it is uninformative at best and misleading at worst. The nature and function of kata training are better conveyed by the phrase “pattern practice.”

Students engaged in pattern practice rehearse combinations of techniques and countertechniques, or sequences of such combinations, arranged by their teachers. In Chinese, Korean, and Okinawan boxing schools, such training often takes the form of solo exercises, while in both traditional and modern Japanese fighting arts students nearly always work in pairs, with one partner designated as the attacker or opponent, and the other employing the techniques the exercise is designed to teach.

In many modern martial art schools and systems, pattern practice is only one of several more or less coequal training methods, but in the older schools it was and continues to be the pivotal method of instruction. Many schools teach only through pattern practice. Others employ adjunct learning devices, such as sparring, but only to augment kata training, never to supplant it.

The preeminence of pattern practice in traditional martial art training often confuses or bemuses modern observers, who characterize it as a kind of ritualized combat, a form of shadowboxing, a type of moving meditation, or a brand of calisthenic drill. But while pattern practice embraces elements of all these things, its essence is captured by none of them. For kata is a highly complex teaching device with no exact analogy in modern sports pedagogy. Its enduring appeal is a product of its multiple functions.

On one level, a school’s kata form a living catalog of its curriculum and a syllabus for instruction. Both the essence and the sum of a school’s teachings—the postures, techniques, strategies, and philosophy that comprise it—are contained in its kata, and the sequence in which students are taught the kata is usually fixed by tradition and/or by the headmaster of Women at an annual martial arts festival in Seattle, Washington, perform kata (forms) in unison. (Bohemian Nomad Picture-makers/Corbis) the school. In this way pattern practice is a means to systematize and regularize training and to provide continuity within the art or school from generation to generation, even in the absence of written instruments for transmission. In application, the kata practiced by a given school can and do change from generation to generation—or even within the lifetime of an individual teacher—but they are normally considered to have been handed down intact by the founder or some other important figure in the school’s heritage. Changes, when they occur, are viewed as being superficial, adjustments to the outward form of the kata; the key elements—the marrow—of the kata do not change. By definition, more fundamental changes (when they are made intentionally and acknowledged as such) connote the branching off of a new system or art.

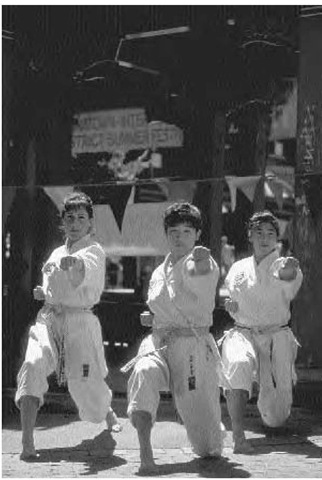

Women at an annual martial arts festival in Seattle, Washington, perform kata (forms) in unison.

But the real function of pattern practice goes far beyond this. The importance of this learning device in traditional East Asian martial—and other—art training stems from the belief that it is the most efficient vehicle for passing knowledge from teacher to student, an idea that in turn derives from broader Chinese educational models.

Learning through pattern practice is a direct outgrowth of Confucian pedagogy and its infatuation with ritual and ritualized action. This infatuation is predicated on the conviction that man fashions the conceptual frameworks he uses to order—and thereby comprehend—the chaos of raw experience through action and practice. One might describe, explain, or even defend one’s perspectives by means of analysis and rational argument, but one cannot acquire them in this way. Ritual is stylized action, sequentially structured experience that leads those who follow it to wisdom and understanding. Therefore, it follows that those who seek knowledge and truth must be carefully guided through the right kind of experience if they are to achieve the right kind of understanding. For the early Confucians, whose principal interest was the proper ordering of the state and society, this need meant habituating themselves to the codes of what they saw as the perfect political organization, the early Zhou dynasty. For martial art students, it means ritualized duplication of the actions of past masters.

Confucian models—particularly Zhu Xi’s concept of investigating the abstract through the concrete and the general through the particular, but also Wang Yangming’s emphasis on the necessity of unifying knowledge and action—dominated most aspects of traditional education in China, Korea, and Japan, not just martial art training. In Japan, belief in the efficacy of this approach to learning was further reinforced by the Zen Buddhist tradition of ishin-denshin (mind-to-mind transmission), which stresses the importance of a student’s own immediate experience over explicit verbal or written explanation, engaging the deeper layers of a student’s mind and bypassing the intellect.

Thus, attaining mastery of the martial or other traditional arts came to be seen as an osmosis-like, suprarational process, in which the most important lessons cannot be conveyed by overt explanation. The underlying principles of the art, it was believed, can never be wholly extrapolated; they must be experienced directly—intuited from examples in which they are put into practice.

The role of the teacher in this educational model is to serve as exemplar and guide, not as lecturer or conveyor of information. Traditional martial art teachers lead students along the path to mastery of their arts, they do not tutor them. Instruction is viewed as a gradual, developmental process in which teachers help students to internalize the key precepts of doctrine. The teacher presents the precepts and creates an environment in which the student can absorb and comprehend them, but understanding— mastery—of these precepts comes from within, the result of the student’s own efforts. The overall process might be likened to teaching a child to ride a bicycle: Children do not innately know how to balance, pedal, and steer, nor will they be likely to discover how on their own. At the same time, no one can fully explain any of these skills either; one can only demonstrate them and help children practice them until they figure out for themselves which muscles are doing what at which times to make the actions possible.

Pattern practice in martial art also bears some resemblance to medieval (Western) methods of teaching painting and drawing, in which art students first spent years copying the works of old masters, learning to imitate them perfectly, before venturing on to original works of their own. Through this copying, they learned and absorbed the secrets and principles inherent in the masters’ techniques, without consciously analyzing or extrapolating them. In like manner, kata are the “works” of a school’s current and past masters, the living embodiment of the school’s teachings. Through their practice, students make these teachings a part of themselves and later pass them on to students of their own.

Many contemporary students of Japanese, Chinese, and Korean martial art, particularly in the West, are highly critical of pattern practice, charging that it leads to stagnation, fossilization, and empty formalism. Pattern practice, they argue, cannot teach students how to read and respond to a real—and unpredictable—opponent. Nor can pattern practice alone develop the seriousness of purpose, the courage, decisiveness, aggressiveness, and forbearance vital to true mastery of combat. Such skills, it is argued, can be fostered only by contesting with an equally serious opponent, not by dancing through kata. Thus, in place of pattern practice many of these critics advocate a stronger emphasis on free sparring, often involving the use of protective gear to allow students to exchange blows with one another at full speed and power without injury.

Kata purists, on the other hand, retort that competitive sparring does not produce the same state of mind as real combat and is not, therefore, any more realistic a method of training than pattern practice. Sparring also inevitably requires rules and modifications of equipment that move trainees even further away from the conditions of duels and the battlefield. Moreover, sparring distracts students from the mastery of the kata and encourages them to develop their own moves and techniques before they have fully absorbed those of the system they are studying.

Moreover, they say, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that pattern practice is meant to be employed only as a tool for teaching and learning the principles that underlie the techniques that make up the kata. Once these principles have been absorbed, the tool is to be set aside. A student’s training begins with pattern practice, but it is not supposed to end there. The eventual goal is for students to move beyond codified, technical applications to express the essential principles of the art in their own unique fashion, to transcend both the kata and the techniques from which they are composed, just as art students moved beyond imitation and copying to produce works of their own.

But while controversy concerning the relative merits of pattern practice, free sparring, and other training methods is often characterized as one of traditionalists versus reformers, it is actually anything but new. In Japan, for example, the conflict is in fact nearly 300 years old, and the “traditionalist” position only antedates the “reformist” one by a few decades.

The historical record indicates that pattern practice had become the principal means of transmission in Japanese martial art instruction by the late 1400s. It was not, however, the only way in which warriors of the period learned how to fight. Most samurai built on insights gleaned from pattern practice with experience in actual combat. This was, after all, the “Age of the Country at War,” when participation in battles was both the goal and the motivation for martial training. But training conditions altered considerably in the seventeenth century. First, the era of warring domains came to an end, and Japan settled into a 250-year Pax Tokugawa. Second, the new Tokugawa shogunate placed severe restrictions on the freedom of samurai to travel outside their own domains. Third, the teaching of martial art began to emerge as a profession. And fourth, contests between practitioners from different schools came to be frowned upon by both the government and many of the schools themselves.

One result of these developments was a tendency for pattern practice to assume an enlarged role in the teaching and learning process. For new generations of first students and then teachers who had never known combat, kata became their only exposure to martial skills. In some schools, skill in pattern practice became an end in itself. Kata grew showier and more stylized, while trainees danced their way through them with little attempt to internalize anything but the outward form. By the late seventeenth century, self-styled experts on proper samurai behavior were already mourning the decline of martial training. In the early 1700s, several sword schools in what is now Tokyo began experimenting with equipment designed to permit free sparring at full or near-full speed and power, while at the same time maintaining a reasonable level of safety. This innovation touched off the debate that continues to this day.

In any event, one should probably not make too much of the quarrels surrounding pattern practice, for the disagreements are largely disputes of degree, not essence. For all the controversy, pattern practice remains a key component of traditional East Asian martial art. It is still seen as the core of transmission in the traditional schools, the fundamental means for teaching and learning that body of knowledge that constitutes the art.