A typical definition of the duel holds that it is a “combat between two persons, fought with deadly weapons by agreement, usually under formal conditions and in the presence of witnesses (seconds) on each side” or “any contest between two antagonists” (Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary).

Discussions of dueling abound, but—except for Mr. Webster—precise definitions are missing. Characteristics of the duel, however, are in most discussions agreed upon:

1. Duelists fight with matched weapons, which are lethal

2. Duelists agree upon conditions, such as time, place, weapons, who should be present

3. Duelists are from the same social class

4. Motives range from preserving honor to revenge to the killing of a rival, with honor most frequently mentioned

Yet, a slight fuzziness remains as to what dueling is, making the classification of some encounters difficult. There is even fuzziness as to how dueling and duelist should be spelled. Webster gives the first spelling as a single l, the second as two ls. Webster’s gives both dueling and duelling, both duelist and duellist, and considers both spellings equally acceptable.

The weapons used in duels are handheld personal weapons, the most common being bladed weapons (swords, sabers, rapiers, and knives) and firearms (generally single-shot pistols). Although the combatants may not intend to kill each other, the weapons used have that potential. Thus piano duels in late eighteenth-century Germany, or for that matter any musical contest, such as the Eskimo song duel, do not qualify as true duels. Differently equipped champions from different military forces, such as David and Goliath (First topic of Samuel, Old Testament), probably should also not be considered duelists, whereas similarly equipped Zulu warriors carrying shields and throwing spears who have stepped forward from their ranks to challenge each other can perhaps be considered duelists. It is harder, though, to decide whether military snipers with scoped rifles hunting each other in Vietnam or fighter pilots in that war or in earlier wars are duelists. Perhaps they should not be considered such because no rules are fol-lowed—ambushing whether in the jungle or from behind clouds being the primary tactic—rather than because of minor differences in weapons.

Duels are staged, not for the public, but before select witnesses, assistants (called in English seconds), and physicians. News of a duel, however, becomes public when word spreads of a wounding or fatality. Although duels are almost always between individuals, there is the possibility that they could be between teams. American popular literature and its movies abound with gunfights. Are these duels? When the Earp brothers met the Clanton and McLaury brothers for a gunfight at the OK Corral, was this a duel? Probably not, because witnesses and the other members of the typical duelist’s entourage were not invited. Later, both Morgan and Virgil Earp were ambushed in separate encounters, with Morgan killed and Virgil crippled. Wyatt later killed the presumed assailants, probably in ambushes.

Although equal rank is not given as a defining attribute by Webster’s, nearly all scholars who have studied the duel emphasize that duelists are from the same social class. If a lower-class person issues a challenge to an upper-class person, it is ignored and seen as presumptuous. The custom of dueling has died out in the English-speaking world, but when it was prevalent, it was considered bad form to challenge royalty, representatives of the Crown such as royal governors, and clergy. Indeed, it was treason to contemplate the death of the king or one of his family members. If the challenge came from a social equal, it might be hard to ignore. If the upper-class person chose not to ignore the lower-class person’s challenge or insults, he might assault him with a cane or horsewhip.

The notion that gentlemen caned or horsewhipped men of lesser social status had symbolic significance. Any person hit with a cane or lashed with a whip was being told in a very rough and public way that he did not rank as high as his attacker; hence the importance of the choice of weapons by southern senator Preston Brooks for his merciless attack on New England senator Charles Sumner in Washington in 1856.

Sumner, in a speech, had used such words as “harlot,” “pirate,” “falsifier,” “assassin,” and “swindler” to describe elderly South Carolina senator Andrew Pickens Butler. Preston Brooks, Butler’s nephew, sought out Sumner and is reputed to have said: “Mr. Sumner, I have read your speech carefully, and with as much calmness as I could be expected to read such a speech. You have libeled my State, and slandered my relation, who is aged and absent, and I feel it to be my duty to punish you for it.” The punishment followed, and Sumner was caned senseless (Williams 1980, 26).

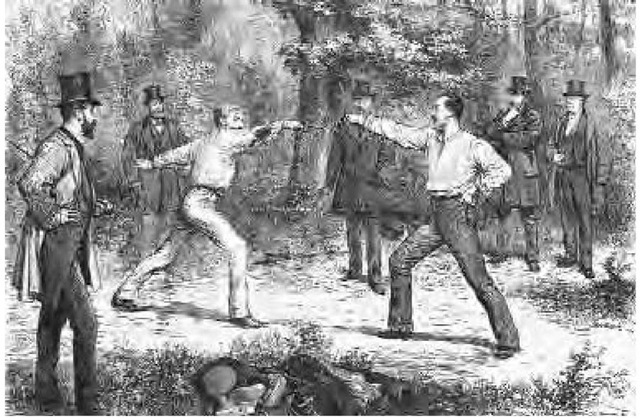

A Code of Honor—A Duel in the Bois de Boulogne, Near Paris. This illustration of a typical duel appeared in the January 8, 1875, edition of Harper’s Weekly and clearly shows all the elements of a “duel.”

General Andrew Jackson, future president of the United States, attempted in 1813 to horsewhip H. Benton, a future U.S. senator, but Benton reached for a pistol while Jackson dropped the whip and drew his own firearm. Benton’s younger brother Jesse, who had the grudge against Jackson, was on the scene; he shot Jackson with a pistol loaded with a slug of lead and two bullets. Jackson’s shoulder was shattered and his left arm pierced, but he refused amputation. Fifteen years later, when both Andrew and were U.S. senators, they became reconciled. During Jackson’s presidency (1829-1837), Benton was a staunch supporter, and on Jackson’s death in 1847 Benton eulogized him. Both Jackson and Benton killed men in duels.

Although motives for challenging and accepting a duel can vary, honor is most frequently mentioned. For members of an upper class, honor is directly linked to class membership. Dueling not only defines who is in the upper class, but it also projects the message that the upper class is composed of honorable men. To decline challenges from members of one’s own class can result in diminished class standing. For members of a lower class to decline to fight can also place them in physical jeopardy; they may become the targets of bullies who would steal from them, take girlfriends or mates, or injure them for sport. Upper-class members can call upon the police authority of the state to protect them. When unimportant people request protection, they are often ignored (unless perhaps they are spies or informers for the state).

A survey of armed combat among peoples without centralized political systems (i.e., those who live in bands and tribes) reveals numerous encounters that resemble dueling but fail to meet all four characteristics. Weapons are not matched, there are no agreed-upon conditions (or at least there is no evidence for such), or the social position of the combatants differs (social stratification is not found in bands, but may occur in tribes). Since motives can vary, the characteristic four cannot be used to rule out an armed combat that meets the other three characteristics. Sometimes, however, the criteria are met. Several examples of armed combat will be examined. The purpose of the survey is not to create a taxonomy but to reveal the conditions under which dueling arises. Several conclusions may be drawn from the following examples.

Although armed combat occurs among bands (usually hunters and gatherers), dueling, if it occurs at all, is rare. Among more politically complex social units known as tribes, dueling sometimes occurs. When it does, it is usually between combatants from different political communities, which are sometimes even culturally different. The survey indicates that dueling has its origin in the military, particularly within those societies that develop elite warriors. While nearly all societies have military organizations, by no means all warring societies produce elite warriors and a warrior tradition. Put another way, in political systems that are not centralized, every able-bodied male becomes a warrior, but in some societies some men become specialists in the use of weapons. If this occurs, there emerges a military elite with a warrior tradition. (Militaries that stress subordination of soldiers to the military organization do not develop an elite, even though the society may be highly militaristic.) These elites provide the first duelists. The duels take place, as noted above, between different political communities, rather than within a single political community. The combatants stand in front of their respective military organizations and represent them. This pattern is also found among peoples with centralized political systems (chiefdoms and states). At this level of sociopolitical complexity, duels between military personnel may occur within the political community. However, in some societies another factor—feuding—comes into play, which strongly works against the development of internal dueling. Feuding societies do not have dueling. In societies without feuding, those no longer in the military and civilians imitating them may also engage in duels provided they are of the same social class, stratification being a characteristic of most centralized political systems. Middle and lower classes may imitate upper classes and/or adopt their own forms of dueling. Thus, dueling first arises in warfare and is then transferred to the civilian realm. The evidence suggests the following sequence of stages: (1) no duels, (2) duels between elite warriors from two political communities, (3) duels between military personnel within a political community, (4) duels between civilians within a political community.

For those societies at the first two stages, the following features are apparent. In nearly all uncentralized political systems every able-bodied man carries weapons for hunting—the spear, the bow and arrow, or the club. These weapons can also be used in warfare, assassinations, executions, self-defense, and dueling. A two-component warfare pattern consisting of ambushes and lines occurs in nearly all uncentralized political systems that engage in warfare. Ambushes combine surprise with a shoot-on-sight response, with better weapons than one’s enemies if possible—no duel here. Line formations, however, may place opposing combatants a short distance from each other. Here is the place to start looking for duels. Paintings on rock walls provide the first evidence for armed encounters that could be duels. In Arnham Land, northern Australia, 10,000 years ago, Aborigines depicted warriors confronting each other with boomerangs, used as throwing and shock weapons, and barbed spears. Spears are shown plunged into fallen figures. Given the multiplicity of weapons both in flight and sometimes lodged in one figure, these scenes appear to illustrate line formations rather than duels. These native Australians, as well as !Kung Bushmen of South Africa, went armed most of the time. For egalitarian societies, James Woodburn has noted that “hunting weapons are lethal not just for game animals but also for people.” He describes “the access which all males have to weapons among the !Kung [and other hunting and gathering peoples]. There are serious dangers in antagonizing someone. . . . [H]e could respond with violence. . . . Effective protection against ambush is impossible” (1982, 436). No duel here.

Tribes, the more developed of the two types of uncentralized political systems, provide examples of dueling. The line formations of the Dani of Highland New Guinea place enemy warriors in direct confrontation. The ethnographic movie Dead Birds by Robert Gardiner shows individual spear-throwers skirmishing. Although weapons are matched, this is not a duel. The confrontation arose during a battle, and there was no pre-arrangement for these warriors to meet. While the Zulu were still at the tribal level of sociopolitical complexity (ca. 1800) they engaged in “dueling battles”:

When conflict arose between tribes, a day and a place were arranged for settling the dispute by combat. On that day the rival tribes marched to battle, the warriors drawing up in lines at a distance of about 100 yards apart. Behind the lines stood the remaining members of each tribe, who during the battle cheered their kinsmen on to greater effort. The warriors carried five-foot tall, oval shields and two or three light javelins. These rawhide shields, when hardened by dipping in water, could not be penetrated by the missiles. Chosen warriors, who would advance to within 50 yards of each other and shout insults, opened the combat by hurling their spears. Eventually more and more warriors would be drawn into the battle until one side ceased fighting and fled. (Otterbein 1994, 30)

The criteria for dueling seem to be met. Prearranged, challenges by individual warriors, matched weapons, same culture and social class. However, when more warriors join in and a general battle ensues, the duel is over. Zulu “dueling battles” just make it to Stage Two.

Plains Indians of North America provide a better example of dueling. These Native Americans belonged to military societies and were deeply concerned with honor and personal status. The following duel between a Mandan and a Cheyenne warrior recounted by Andrew Sanders tells it all:

Formal single combats between noted warriors or between champions of groups are reported from warrior societies around the world. They are frequently reported for nineteenth-century Plains Indians. Sometimes they involved behavior comparable to the medieval European idea of chivalry, at least under the proper set of circumstances. A classic example is the American artist George Catlin’s account of a duel between the noted Mandan leader Mato-Tope (“Four Bears”) and a Cheyenne war chief. When a party of Mandans met a much larger Cheyenne war party, Mato-Tope made towards them and thrust his lance into the ground. He hung his sash (the insignia of his position in his military association) upon it as a sign that he would not retreat. The Cheyenne chief then challenged Mato-Tope to single combat by thrusting his ornate lance (the symbol of his office in his military association) into the ground next to that of Mato-Tope. The two men fought from horseback with guns until Mato-Tope’s powder horn was destroyed. The Cheyenne threw away his gun so that they remained evenly matched. They fought with bow and arrow until Mato-Tope’s horse was killed, when the Cheyenne voluntarily dismounted and they fought on foot. When the Cheyenne’s quiver was empty both men discarded bow and shield and closed to fight with knives. Mato-Tope discovered that he had left his knife at home, and a desperate struggle ensued for the Cheyenne’s weapon. Although wounded badly in the hand and several times in the body, Mato-Tope succeeded in wresting the Cheyenne’s knife from him, killing him, and taking his scalp. Consequently, among his war honors Mato-Tope wore a red wooden knife in his hair to symbolize the deed, and the duel was one of the eleven war exploits painted on his buffalo robe. (1999, 777)

This pattern of an elite warrior stepping forward to take on a challenger is found in centralized political systems but gives way under pressure of intensifying warfare. The next example, from a chiefdom-level society, took place in northeastern North America between the Iroquois and their enemies the Algonquins. Prior to 1609, these Native Americans wore body armor, carried shields, and fought with bows and arrows. The opposing sides formed two lines in the open; war chiefs would advance in front of their lines and challenge each other. Samuel de Champlain, the French explorer, was with the Algonquins; he recounts his reaction to the encounter: “Our Indians put me ahead some twenty yards, and I marched on until I was within thirty yards of the enemy, who as soon as they caught sight of me halted and gazed at me and I at them. When I saw them make a move to draw their bows upon us, I took aim with my arquebus and shot straight at one of the three chiefs, and with this shot two fell to the ground and one of their companions was wounded who died thereof a little later. I had put four bullets into my arquebus” (Otterbein 1994, 5). Iroquois dueling came, thus, to an abrupt end. Iroquois and Huron campaigns and battles in the next forty years provide no examples of dueling.

Zulu “dueling battles” also ceased as warfare intensified. As the Zulu evolved into a chiefdom and then a state, a remarkable elite warrior, Shaka, devised a new weapon and new tactics in approximately 1810. He replaced his javelins with a short, broad-bladed stabbing spear, retained his shield, but discarded his sandals in order to gain greater mobility. By rushing upon his opponent he was able to use his shield to hook away his enemy’s shield, thus exposing the warrior’s left side to a spear thrust. Shaka also changed military tactics by arranging the soldiers in his command—a company of about 100 men—into a close-order, shield-to-shield formation with two “horns” designed to encircle the enemy. Shaka’s killing of an enemy warrior with a new weapon and a new tactic brought an end to Zulu duels.

In the ancient Middle East (Middle Bronze Age, 2100 to 1570 B.C.), Semitic tribes of Palestine and Syria had individual combat “between two warrior-heroes, as representatives of two contending forces. Its outcome, under prearranged agreement between both sides, determined the issue between the two forces” (Yadin 1963, 72). Although Yadin refers to these contests as duels, the combatants were not equipped the same. In the example given, the Egyptian man who was living with the Semites had a bow and arrow and a sword; he practiced with both before the “duel.” The enemy warrior had a shield, battle-ax, and javelins. The javelins missed, but the arrows found their mark, the neck. The Egyptian killed his opponent with his own battle-ax. Duels of this nature continued to be fought as the tribes developed into centralized political systems. In the most famous duel of all—approximately 3,000 years ago—the First topic of Samuel tells us that Goliath, a Philistine, was equipped with a coat of mail, bronze helmet, bronze greaves to protect the legs, and a javelin. He was also accompanied by a shield bearer. David, later to become king of the Hebrews, armed with a sling, could “operate beyond the range of Goliath’s weapons” (Yadin 1963, 265). Yadin insists that these contests are duels because they took “place in accordance with prior agreement of the two armies, both accepting the condition that their fate shall be decided by the outcome of the contest” (265). Yadin describes other duels where the soldiers are similarly equipped with swords (266-267). These are duels. Stage Two had been reached.

Duels between men of the same military organization, Stage Three, occur during more recent history in the West—that is, during the Middle Ages, and civilian duels, Stage Four, occur even more recently in Euro-American Dueling. Stage Three is not easily reached because a widespread practice, feuding, works against the development of dueling within polities. Approximately 50 percent of the world’s peoples practice feuding (the practice of taking blood revenge following a homicide). In feuding societies honor focuses not upon the individual, as it does in dueling societies, but upon the kinship group. If someone is killed in a feuding society, his or her relatives seek revenge by killing the killer or a close relative of the killer, and three or more killings or acts of violence occur. In a feuding society, no one would dare to intentionally kill another in a duel. If a duel occurred in an area where feuding was an accepted practice, the resulting injuries and possible deaths would start a feud between the kinship groups of the participants. In other words, dueling neither develops in nor is accepted by feuding societies: Where feuds, no duels. Data from the British Isles support this conclusion. Feuding occurred over large areas of Scotland, and arranged battles between small groups of warriors (say thirty on a side) sometimes took place; dueling was rare in Scotland, and when it did occur it was likely to be in urban centers such as Edinburgh.

Stage Three dueling developed in Europe during the early Middle Ages, in areas where feuding had waned. Dueling within polities by elite military personnel is regarded by most scholars as a uniquely European custom, although they recognize that in feudal Japan samurai warriors behaved similarly. Monarchs at war, such as the Norman kings, banned feuding. (This is consistent with the cross-cultural finding of Otterbein and Ot-terbein that centralized political systems, if at war, do not have feuding even if patrilocal kinship groups are present.)

Several sources for the European duel have been proposed. Kevin McAleer suggests a Scandinavian origin: “The single combat for personal retribution had its beginnings as an ancient Germanic custom whose most ardent practitioners were pagan Scandinavians. They would stage their battles on lonely isles, the two nude combatants strapped together at the chest.

A knife would be pressed into each of their hands. A signal would be given—at which point they would stab each other like wild beasts. They would flail away until one of them either succumbed or begged for quarter” (1994, 13).

These “duels” are perhaps the origin of trial by combat or the judicial combat. The belief was that God would favor the just combatant and ensure his victory. Authorities would punish the loser, often hanging him. Judicial combats may have occurred as early as a.d. 500. Popes sanctioned them. Such trials largely disappeared by 1500. During the interval, the practice was “increasingly a prerogative of the upper classes, accustomed to the use of their weapons” (Kiernan 1988, 34).

Another possible source for the duel was the medieval tournament, which seems to have had its origin in small-scale battles between groups of rival knights. By the fourteenth century, the joust, or single combat, took the place of the melee, as the small-scale battle was called. Sometimes blunted weapons were used and sometimes they were not. Kiernan asserts that “all the diverse forms of single combat contributed to the ‘duel of honour’ that was coming to the front in the later Middle Ages, and was the direct ancestor of the modern duel. Like trial by combat or the joust, it required official sanction, and took place under regulation” (1988, 40).

Chivalry developed, and by the 1500s treatises on dueling were published. The duel in modern form became a privilege of the noble class. Stage Four was finally reached. For an individual, the ability to give and accept challenges defined him as not only a person of honor, but as a member of the aristocracy. As Europe became modern, the duel did not decline as might be expected, for the duel became attractive to members of the middle class who aspired to become members of the gentry. Outlawing of the duel by monarchs and governments did not prevent the duel’s spread. The duel even spread to the lower classes, whose duels Pieter Spierenburg (1998) has referred to as “popular duels” in contrast to “elite duels.” The practice even persisted into the twentieth century.

Perhaps because the duel persisted in Germany until World War II, creating a plethora of information, recent scholarly attention has focused on the German duel in the late nineteenth century. Three theories for its persistence have been offered: (1) Kiernan sees the duel, including the German duel, as a survival from a bygone era that was used by the aristocracy as a means of preserving their privileged position; (2) Ute Frevert argues that the German bourgeois adopted dueling as a means by which men could achieve and maintain honor by demonstrating personal bravery; (3) McAleer views the German duel as an attempt at recovery of an illusory past, a practice through which men of honor, by demonstrating courage, could link themselves to the ruling warrior class of the Middle Ages. The theories are different, yet they have similarities, and together they shed light on the nature of the German duel.

Dueling was brought to the United States by European army officers, French, German, and English, during the American Revolution. Fundamental to the formal duel, an aristocratic practice, is the principle that duels are fought by gentlemen to preserve their honor. Dueling thus became established only in those regions of the United States that had established aristocracies that did not subscribe to pacifist values, namely the lowland South, from Virginia through the low country of South Carolina to New Orleans. Two theories have been offered to explain the duel in America. The first asserts that the rise and fall of dueling went hand in hand with the rise and fall of the southern slave-owning aristocracy. As Jack K. Williams puts it, “The formal duel fitted easily and well into this concept of aristocracy. The duel, as a means of settling disputes, could be restricted to use by the upper class. Dueling would demonstrate uncompromising courage, stability, calmness under stress” (1980, 74). Lee Kennett and James LaVeme Anderson, on the other hand, point out, “Its most dedicated practitioners were army and navy officers, by profession followers of a quasi-chivalrous code, and southerners, who embraced it most enthusiastically and clung to it longest. Like most European institutions, dueling suffered something of a sea change in its transfer to the New World. In the Old World it had been a badge of gentility; in America it became an affirmation of manhood. . . . Dueling was a manifestation of a developing society and so it was natural that men resorted to it rather than the legal means of securing a redress of grievance” (1975, 141, 144).

Yet the duel occurred primarily in areas where there were courts. “The duel traveled with low-country Southerners into the hill country and beyond, but frontiersmen and mountain people were disinclined to accept the trappings of written codes of procedure for their personal affrays!” (Williams 1980, 7). Several reasons seem quite apparent. The people of Appalachia were not aristocrats, many could barely read or write, and feuding as a means of maintaining family honor was well established. As argued above, if a duel occurs in an area where feuding is an accepted practice, the resulting injuries and possible deaths will start a feud; dueling can enter a region only if the cultural practices do not include feuding. Thus feuding and dueling do not occur in the same regions.

American dueling, unlike its European counterpart in the nineteenth century, was deadly. In Europe the goal of the duelist was to achieve honor by showing courage in the face of death. Winning by wounding or killing the opponent was unnecessary. On the other hand, many American duelists tried to kill their opponents. This difference was noted by Alexis de Toc-queville in 1831 in his Democracy in America: “In Europe, one hardly ever fights a duel except in order to be able to say that one has done so; the offense is generally a sort of moral stain which one wants to wash away and which most often is washed away at little expense. In America one only fights to kill; one fights because one sees no hope of getting one’s adversary condemned to death” (Hussey 1980, 8).

Dueling in the American South occurred from the time of the Revolution to the Civil War. Duels were frequent. Many of the duelists were prominent political figures, and the consequences were often fatal. Anyone doubting this statement should look at the first five denominations of U.S. paper money. One man whose head is shown died in a duel, while another killed a man in a duel: respectively, Alexander Hamilton and Andrew Jackson.

Political opponents Alexander Hamilton and Vice President Aaron Burr met on the dueling ground at Weehawken, New Jersey, on July 11, 1804, with their seconds. Hamilton’s persistent libeling of Burr precipitated Burr’s challenge. As the challenged party, Hamilton supplied the matched dueling pistols. The seconds measured the distance, ten full paces. The duelists loaded the pistols in each other’s presence, after which the parties took their stations. On the command “Present,” each raised his pistol and fired. Apparently, Burr fired first, with the ball hitting Hamilton in the right side; Hamilton swayed and the pistol fired, missing Burr. A surgeon friend of Hamilton attended to him. The surgeon’s account says that Hamilton had not intended to fire, while Burr’s second claimed Hamilton fired first. It was obvious to both Hamilton and the surgeon that he was fatally wounded.

Andrew Jackson’s killing of Charles Dickinson in a duel in Logan County, Kentucky, on May 30, 1806, is less well known. The animosity between them grew out of a dispute about stakes in a horse race that did not take place. Jackson issued the challenge, which Dickinson eagerly accepted, although he did not have a set of dueling pistols. Yet Dickinson, a snap-shooter who did not take deliberate aim, practiced en route to the dueling field. The agreed-upon distance was 24 feet. Jackson, a thin and ascetic man, dressed in large overgarments and twisted his body within his coat so that it was almost sidewise. Dickinson was a large, florid man. On the command to fire, Dickinson shot, and Jackson held his fire. Jackson was hit, his breastbone scored and several ribs fractured, but he stood his ground. Jackson’s twist of body had saved his life. Jackson aimed and pulled the trigger, but the hammer stopped at half cock. He recocked it and took aim before firing. The bullet passed through Dickinson’s body below the ribs. Dickinson took all day to bleed to death. Jackson was later criticized for recocking his pistol, something an honorable man would not have done. But each man wanted to kill the other.