Sirenia are the order of placental mammals comprising , modern sea cows (manatees and dugongs) and their extinct relatives. They are the only herbivorous marine mammals now living, and the only herbivorous mammals ever to have become totally aquatic. Sirenians have a known fossil record extending over some 50 million years (early Eocene-Recent). They attained a modest diversity in the Oligocene and Miocene, but since then have declined as a result of climatic cooling, other oceanographic changes, and human depredations. Only two genera and four species survive today: the three species of manatees (Trichechtts) live along the Atlantic coasts and rivers of the Americas and West Africa; one. the Amazonian manatee, is found only in fresh water. The dugong (Dugong) lives in the Indian and southwest Pacific oceans. [For comprehensive references to technical as well as popular publications on fossil and living sirenians, see Domning (1996).]

I. Sirenian Origins

The closest living relatives of sirenians are Proboscidea (elephants). The Sirenia, the Proboscidea, the extinct Desmostylia, and probably the extinct Embrithopoda together make up a larger group called Tethytheria, whose members (as the name indicates) appear to have evolved from primitive hoofed mammals (condylarths) in the Old World along the shores of the ancient Tethys Sea. Together with Hyracoidea (hyraces), tethytheres seem to form a more inclusive group long referred to as Paenungulata. The Paenungulata and (especially) Tethytheria are among the least controversial groupings of mammalian orders and are strongly supported by most morphological and molecular studies. Their ancestry is remote from that of cetaceans or pinnipeds; sirenians reevolved an aquatic lifestyle independently of (though simultaneously with) cetaceans, ultimately displaying strong convergence with them in body form.

II. Early History, Anatomy, and Mode of Life

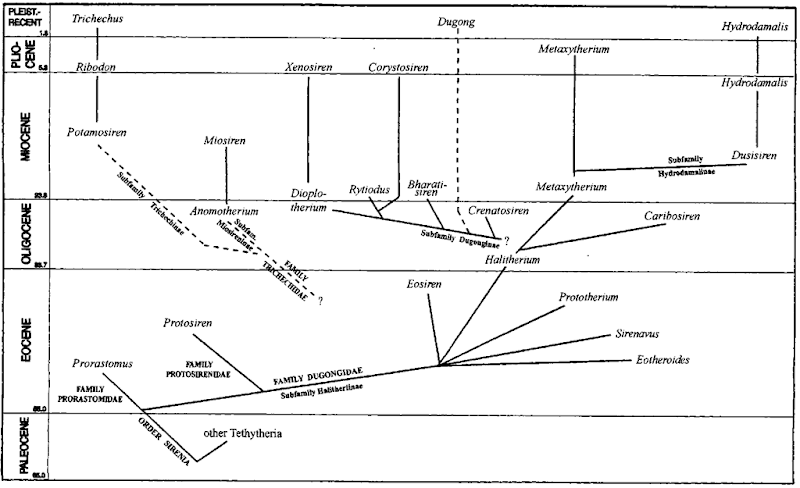

Sirenians first appear in the fossil record in the early Eocene, and the order was already diverse by the middle Eocene (Fig. 1). As inhabitants of rivers, estuaries, and nearshore marine waters, they were able to spread quickly along the coasts of the world’s shallow tropical seas; in fact, the most primitive sirenian known to date (Prorastomus) was found not in the Old World but in Jamaica.

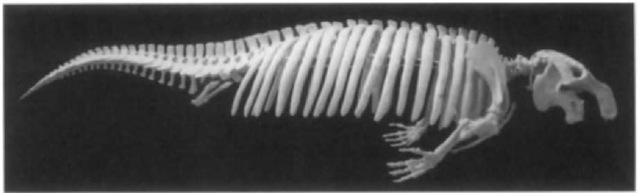

The earliest sea cows (families Prorastomidae and Proto-sirenidae, both confined to the Eocene) were pig-sized, four-legged amphibious creatures. By the end of the Eocene, with the appearance of the Dugongidae, sirenians had taken on their modern, completely aquatic, streamlined body form, featuring flipper-like front legs, no hind legs, and a powerful tail with a horizontal caudal fin, whose up-and-down movements propel them through the water, as in whales and dolphins (Fig. 2). The last-appearing of the four sirenian families (Trichechi-dae) apparently arose from early dugongids in the late Eocene or early Oligocene. The sirenian fossil record now documents all the major stages of hindlimb and pelvic reduction from completely “terrestrial” morphology to the extremely reduced condition of the pelvis seen in modern manatees, thereby providing one of the most dramatic examples of evolutionary change to be seen among fossil vertebrates.

Figure 1 Simplified phytogeny of Sirenia, including only better-known genera. The time scale (at left) is in millions of years. “Ghost lineages” (ancestral groups undocumented by fossils) that span multiple epochal boundaries are shown as dashed lines.

Figure 2 Skeleton of Metaxytherium floridanum, a Miocene halitheriine dugongid. Total length about 3.2 in.

From the outset, sirenians were herbivores and probably depended on seagrasses and other aquatic angiosperms (flowering plants) for food. To this day, almost all members of the order have remained tropical, marine, and eaters of angiosperms. No longer capable of locomotion on land, sirenians are born in the water and spend their entire lives there. Because they are shallow divers with large lungs, they have heavy skeletons, like a diver’s weight belt, to help them stay submerged: their bones are both swollen (pachyostotic) and dense (osteosclerotic), especially the ribs, which are often found as fossils.

The sirenian skull is characterized by an enlarged and more or less downturned premaxillary rostrum, retracted nasal opening, absence of paranasal air sinuses, laterally salient zygomatic arches, and thick, dense parietals fused into a unit with the supraoccipital. Nasals and lacrimals tend to become reduced or lost, and in most forms the pterygoid processes are large and stout. The periotic is snugly enclosed by a socket in the squamosal and is fused with a ring-shaped tympanic. The mandibular symphysis is long, deep, laterally compressed, and typically fused and downturned; in all but prorastomids the mandibular foramen is enlarged to expose the dental capsule. Incisors, where present, are arranged in parallel, longitudinally aligned rows. In all but the most primitive taxa, the infraorbital and mental foramina are enlarged to accommodate the nerve and blood supply to the large, prehensile, vibrissae-studded lips, which are moved by muscular hydrostats (cf. Marshall et al, 1998).

Eocene sirenians, like Mesozoic mammals but in contrast to other Cenozoic ones, have five instead of four premolars, giving them a 3.1.5.3 dental formula. Whether this condition is truly a primitive retention in the Sirenia is still being debated. The fourth lower deciduous premolar (dp4) is trilobed, like that of many other ungulates; this raises the further unresolved question of whether the three following teeth (dp5, ml, and m2) are actually the homologues of the so-called ml-3 in other mammals.

Although the cheek teeth are relied on for identifying species in many other mammalian groups, they do not vary much in morphology among Sirenia but are almost always low-crowned (brachyodont) with two rows of large, rounded cusps (buno-bilophodont). (The most taxonomically informative parts of the sirenian skeleton are the skull and mandible, especially the frontal and other bones of the skull roof; Fig. 3.) Except for a pair of tusk-like first upper incisors seen in most species, front teeth (incisors and canines) are lacking in all but the earliest fossil sirenians, and cheek teeth in adults are commonly reduced in number to four or five on each side of each jaw: one or two deciduous premolars, which are never replaced, plus three molars. As described later, however, all three of the Recent genera have departed in different ways from this “typical” pattern.

Figure 3 Skull of Crenatosiren olseni, an Oligocene dugongine dugongid, in (A) lateral and (B) dorsal views. Note the large incisor tusks in the premaxillae. E, ethmoid; EO, ex-occipital; FR, frontal; ], jugal; L, lacimal; MA, mandible; MX, maxilla; PA, parietal; PM, premaxilla; SQ, squamosal; V, vomer. Scale bar: 5 cm.

III. Dugongidae

Dugongids comprise the vast majority of the species and specimens that make up the known fossil record of sirenians. The basal members ol tins very successful family are placed in the long-lived (Eocene-Pliocene) and cosmopolitan subfamily Halitheriinae (Fig. 1). This paraphyletic group included the well-known fossil genera Halitherium and Metaxytherium, which were relatively unspecialized seagrass eaters.

Metaxytherium (Fig. 2) gave rise in the Miocene to the Hy-drodamalinae, an endemic North Pacific lineage that ended with Steller’s sea cow (Hydrodamalis)—the largest sirenian that ever lived (up to 9 m or more in length) and the only one to adapt successfully to temperate and cold waters and a diet of marine algae. It was completely toothless, and its truncated, claw-like flippers, used for gathering plants and fending off from rocks, contained no finger bones (phalanges). It was hunted to extinction for its meat, fat, and hide circa a.d. 1768.

Another offshoot of the Halitheriinae, the subfamily Dugonginae, appeared in the Oligocene (Fig. 3). Most dugongines were apparently specialists at digging out and eating the tough, buried rhizomes of seagrasses; for this purpose many of them had large, self-sharpening blade-like tusks (Domning, 2001). The modem Dugong is the sole survivor of this group, but it has reduced its dentition (the cheek teeth have only thin enamel crowns, which quickly wear off, leaving simple pegs of dentine) and has (perhaps for that reason) shifted its diet to more delicate seagrasses and ceased to use its tusks for digging.

IV. Trichechidae

Trichechidae have a much less complete fossil record dian dugongids. Their definition has been broadened by Domning (1994) to include Miosireninae, a peculiar and little-known pair of genera that inhabited northwestern Europe in the late Oligocene and Miocene (Fig. 1). Miosirenines had massively reinforced palates and dentitions that may have been used to crush shellfish. Such a diet in sirenians living around the North Sea seems less surprising when we consider that modern dugongs and manatees near the climatic extremes of their ranges are known to consume invertebrates in addition to plants.

Manatees in the strict, traditional sense are now placed in the subfamily Trichechinae. They first appeared in the Miocene, represented by Potamosiren from freshwater deposits in Colombia. Indeed, much of trichechine history was probably spent in South America, whence they spread to North America and Africa only in the Pliocene or Pleistocene.

During the late Miocene, manatees living in the Amazon basin evidently adapted to a diet of abrasive freshwater grasses by means of an innovation still used by their modem descendants; they continue to add on extra teeth to the molar series as long as they live, and as worn teeth fall out at the front, the whole tooth row slowly shifts forward to make room for new ones erupting at the rear. This type of horizontal tooth replacement has often been likened, incorrectly, to that of elephants, but the latter are limited to only three molars. Only one other mammal, an Australian rock wallaby (Peradorcas

![Skull of Crenatosiren olseni, an Oligocene dugongine dugongid, in (A) lateral and (B) dorsal views. Note the large incisor tusks in the premaxillae. E, ethmoid; EO, ex-occipital; FR, frontal; ], jugal; L, lacimal; MA, mandible; MX, maxilla; PA, parietal; PM, premaxilla; SQ, squamosal; V, vomer. Scale bar: 5 cm. Skull of Crenatosiren olseni, an Oligocene dugongine dugongid, in (A) lateral and (B) dorsal views. Note the large incisor tusks in the premaxillae. E, ethmoid; EO, ex-occipital; FR, frontal; ], jugal; L, lacimal; MA, mandible; MX, maxilla; PA, parietal; PM, premaxilla; SQ, squamosal; V, vomer. Scale bar: 5 cm.](http://lh4.ggpht.com/_NNjxeW9ewEc/TNGnD21DEFI/AAAAAAAAPnw/ebPPB0_0uNU/tmp1DF83_thumb_thumb1.jpg?imgmax=800)