The term “river dolphins” has been used traditionally to include the Recent odontocetes living in fresh waters and of which affinities to other groups of odontocetes were unclear. They have been generallv included in the super-family Platanistoidea, mainly because of their freshwater habitat and because they present many plesiornorphic characters relative to other groups such as delphinoids, phvseteroids, or ziphiids (e.g., Slijper, 1936; Simpson, 1945). The four genera of living “river dolphins” (Platanista, Lipotes, Inia, and Pontopo-ria) were, therefore, regarded as belonging to a monophyletic group of primitive odontocetes. Other freshwater (but also partly marine) odontocetes, such as Orcnella (Irrawaddv River dolphin) and Sotalia fluviatilis (tucuxi), were not included in Platanistoidea because of their unanimously accepted close affinities to Delphinoidea. While there was a widespread assumption of their monophyly, the affinities of recent Platanistoids (i.e., “river dolphins”) and referred fossil genera to other living and fossil groups of odontocetes have long been very confused and interpretations diverse. The “platanistoids” or some of their included taxa have been regarded as closely related to several groups of fossil odontocetes, e.g., Squalodontidae, Eurhinodel-phinidae, and “Acrodelphinidae.”

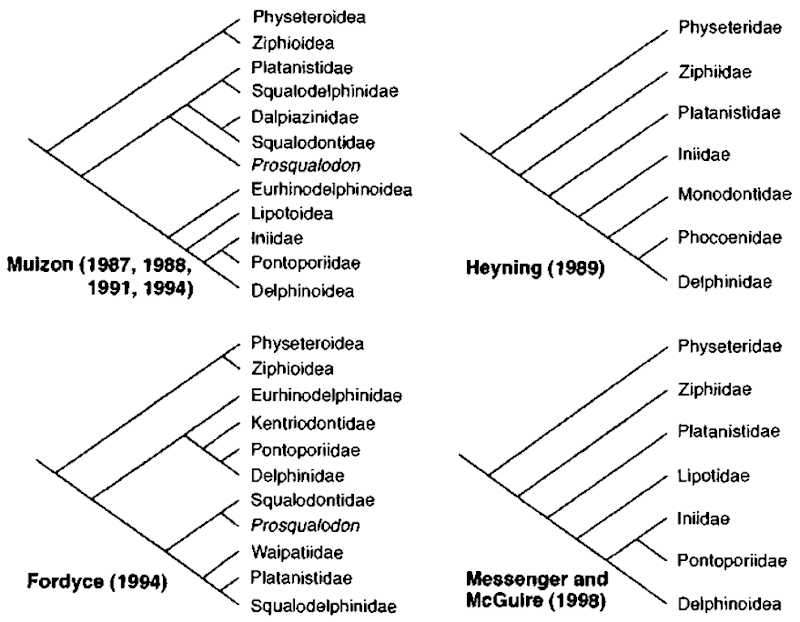

A possible para- or polyphyly of the traditional concept of Platanistoidea was first considered by Muizon (1984) and was confirmed bv further studies (e.g., Muizon, 1987, 1988, 1991, 1994; Heyning, 1989; Fordyce, 1994; Messenger and McGuire, 1998). As expressed in these studies, there now seems to be a consensus on the nonmonophyly of the “river dolphins” and their fossil relatives (Fig. 1). The genus Platanista appears to belong to an early diverging group of odontocetes, and the three other genera (Lipotes, Pontoporia, and Inia) are regarded as closely related to Delphinoidea. Platanista is the Recent representative of a monophyletic group of odontocetes, the Platanistoidea, which was well diversified and widely distributed during the Oligocene and the Miocene. This group, in addition to Platanistidae, includes the fossil families Prosqualodontidae, Squalodontidae, Waipatiidae, Squalodelphinidae, and possiblv Dalpiazinidae. The other “river dolphins” are included with Delphinoidea within the monophyletic infraorder Delphinida (Muizon, 1988). There is no consensus on their position within Delphinida, although they are generally regarded as basal taxa.

I. Platanistoidea

This monophyletic superfamily of odontocetes includes one Recent genus (Platanista) and approximately 15 fossil taxa (according to interpretations) (see Fordyce and Muizon, 2001). As recommended by Muizon (1987) and Fordyce and Muizon (2001), only the genera based, at least, on reasonably complete cranial remains, including ear bones are considered. The monophyly of Platanistoidea is supported by several synapomorphies such as the reduction or loss ol the coracoid process of the scapula, the development of an articular ridge or peg on the periotic, and the ventral deflection of the anterior process of the periotic (Muizon, 1994; Fordyce, 1994). This superfamily includes five (possibly six) families: Squalodontidae, Prosqualodontidae, Dalpi-azinidae, Waipatiidae, Squalodelphinidae, and Platanistidae. In contrast to their Recent representative, all the fossil platanistoids are marine, which would indicate that adaptation to a freshwater environment is probably a derived condition.

Figure 1 Cladograms of recent hypotheses on the affinities of “river dolphins.”

A. Squalodontidae

Squalodonts are the most common fossil platanistoids. They are also called “shark-toothed” dolphins because of their het-erodont dentition, with the posterior teeth being triangular with roughly or finely serrated edges resembling shark teeth. This plesiomorphic condition has often been one of the major arguments to refer many fossil taxa to this family. As a consequence, until recently, the Squalodontidae represented a waste basket of fossil odontocetes with heterodont dentition. Squalodontid genera based on partial or complete skulls are Squalodon, Rellog-gia (a possible synonym of Squalodon). Eosqualodon, and Phoberodon. Synapomorphies of Squalodontidae as defined by Fordyce (1994) are essentially based on the morphology of the periotic, a bone unknown in Phoberodon, Eosqualodon, and Kelloggia. Muizon (1991, 1994) has proposed some cranial synapomorphies of the Squalodontidae, some of which, as mentioned by Fordyce (1994), are probably not securely established. Therefore, it is clear that the monophyly of Squalodontidae still has to be confirmed by a more thorough study of their auditory region. Furthermore, a better knowledge of the anatomy of the enigmatic genus Patriocetus could confirm its introduction into die Squalodontidae, as proposed by Rothausen (1968).

Squalodontidae present the scapula synapomorphies of Platanistoidea (however, this bone is unknown in Eosqualodon and incomplete in Phoberodon). Some other synapomorphies, present in all the Platanistoids except Prosqualodon, are incipi-ently developed in Squalodontidae; such as the overlap of the palatine by the maxilla and the presence of a shallow subcircu-lar fossa in the squamosal dorsolateral to the periotic (see Muizon, 1987, 1991, 1994).

Squalodontidae are cosmopolitan basal platanistoids. All their remains were found in marine coastal environments. Squalodon is present in die Miocene of Europe, Asia, and North America; Eosqualodon is present in the Miocene of Europe; Kelloggia is present in the late Oligocene of Asia; and Phoberodon is from the early Miocene of South America. Undescribed squalodontids have also been found in Australia and New Zealand (Fordyce and Muizon, 2001). Squalodontids are relatively large odontocetes approaching the size of the living Mesopbdon spp. (beaked whales). They had a long rostrum with strongly procumbent anterior teeth (Fig. 2). In fact, the medial incisors were almost horizontal. The teeth were strongly heterodont. The vertex was low and the skull was symmetrical. As in all platanistoids, Squalodontidae have enlarged and slightly concave premaxillary fossae anterolateral to the nares. These fossae received premaxillary sacs of the nasal tract. Premaxillary sacs are tightly related to the presence of nasal plugs and melon, and their presence in Squalodontidae is an indication of efficient echolocation ability.

B. Prosqualodontidae

The single genus Prosqualodon is included in this family. Initially placed in Squalodontidae (e.g., Simpson, 1945; Rothausen, 1968), Prosqualodon has been removed from this family by Muizon (1991) because it does not possess the synapomorphies of the auditory region observed in other platanistoids; however, it was maintained in the superfamily because it bears the scapula synapomorphies of the group. Therefore, Prosqualodon would be the sister group of all the other platanistoids. However, Prosqualodon has also been regarded as member of the the in-fraorder Delphinida on the basis of the presence of the same apomorphic character of the palatine [presence of a lateral lamina as defined by Muizon (1988)] in the two groups. In fact, as stated by Muizon (1994), the palatine-derived character in Delphinida. Fordyce (1994) regarded Prosqualodon as the sister taxon of Squalodon, whereas Fordyce and Muizon (2000) retained the taxon Prosqualodontidae, which they regard as a pla-tanistoid family, although they state that Prosqualodon could also be a squalodontid.

Figure 2 Skulls of Squalodontidae: (a) Eosqualodon langewi-eschei (late Oligocene, Germany), reconstruction of the skull in dorsal view [from Rothausen (1968), modified]; (b) Squalodon bellunensis (early Miocene, Italy), reconstruction of the skull in dorsal view [from Rothausen (1968), modified; (c) S. bellunensis (early Miocene, Italy), skull and mandible in lateral view; (d) Squalodon bariensis (early Miocene, France), skull (apex of the rostrum missing) in ventral view, a and b are reproduced with permission of Paliiontologische Zeitschrift.

Prosqualodon is an austral genus that has been found so far in the early Miocene of Argentina, Australia, and New Zealand. It is a medium-sized odontocete, and its size ranges from a small Globicephala (pilot whale) to a large Tursiops (bottlenose dolphin). As squalodontids, Prosqualodon had heterodont teeth. The anterior teeth are elongated conically and project an-teroventally; the posterior teeth are triangular, low, transversely compressed with a rugose enamel, and bear several denticles on their anterior and posterior crests. The rostrum is short, die vertex is symmetrical, and the braincase is lower than in Squalodon. Premaxillary fossae are clearly present but they are less developed and shallower than in Squalodon (Fig. 3).

C. Dalpiazinidae

The single known genus of the family, Dalpiazina, has been related to the Platanistoidea on the presence of several simi-larities that it shares with Squalodon (see Muizon, 1991, 1994). However, it is noteworthy that none of the platanistoid synapo-morphies are observable on the specimens available and, therefore, the affinities of this family still have to be confirmed. Dalpiazina is a medium-sized odontocete (like a small Tursiops). The rostrum is relatively long and bears honiodont dentition. It is known from the early Miocene of Italy, and some possible dalpiazinids have been discovered in New Zealand (Fordyce et al, 1994).

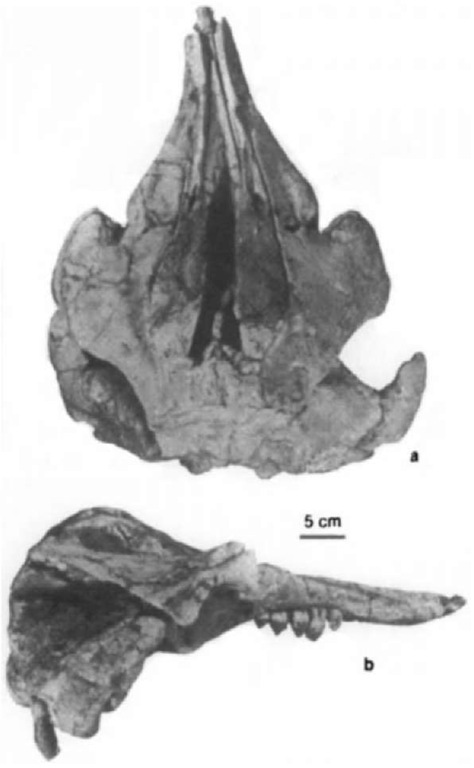

Figure 3 Skull of Prosqualodon australis (early Miocene, Argentina) in dorsal (a) and lateral (b) views.

D. Waipatiidae

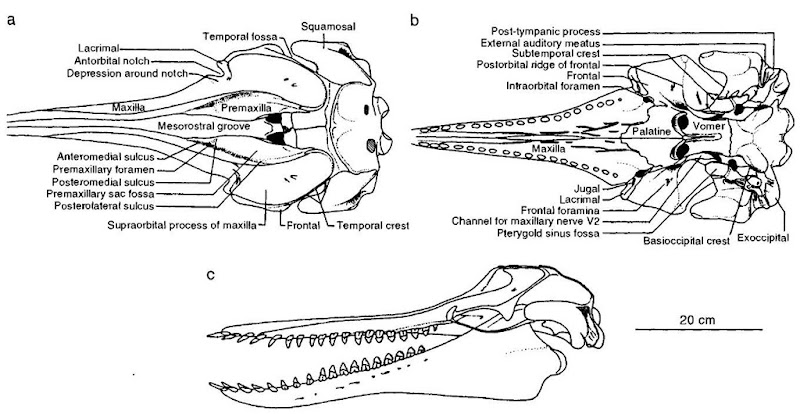

Waipatia is known from a nearly complete skull with ear bones and partial skeleton. This genus presents the auditoiy region synapomorphies of the platanistoids and, although its scapula is unknown, is better placed in this superfamily than in any other group of odontocete (Fordyce, 1994; Fordyce and Muizon, 2001). It is a medium-sized platanistoid similar in size to Tursiops. The rostrum is long and slender (Fig. 4). It bears heterodont teeth but the posterior triangular and double-rooted teeth are smaller than in Squalodontidae. The incisors are conical and strongly procumbent. The skull roof is very low as in squalodontids. The skull of Waipatia shows clear directional asymmetry of the bones. The premaxillary fossae are well developed, and the premaxillae extend posteriorly to the nasals and contact the frontals on the vertex as in the other platanistoids. Waipatia maerewhenua, the single species clearly referred to this family, is from the late Oligocene of New Zealand.

Sulakocetus is a primitive odontocete from the late Oligocene of Asia (Caucasus). It bears heterodont dentition but its posterior double-rooted teeth are small as in Waipatia. Apparently the periotic of the single known skull is unknown (or unprepared) but its tympanic is squalodont-like. The scapula bears a small coracoid process. Because of this character, Stt-lakocetus should be excluded from Platanistoidea. However, it is probable that the small (reduced) size of the process represents an incipient development of the platanistoid condition. This genus has been classified by Fordyce and Muizon (2001) as a possible waipatiid. However, it is clear that more information on its auditory region is needed to clarify the systematic position of Sulakocetus.

E. Squalodelphinidae

This family includes the genera Notocettis, Medocinia, Phocageneus, and Squalodelphis. The four taxa are based on reasonably well-preserved skulls and/or ear bones. Squalodelphinidae present the platanistoid synapomorphies of the scapula (loss of the coracoid process, anterior position of the acromion) and of the ear region (e.g., subcircular fossa, articular ridge of the periotic, morphology of the apex of the tympanic) (see Muizon, 1987, 1994). Squalodelphinidae are cosmopolitan and marine. Notocetus is from the early Miocene of South America and New Zealand; Squalodelphis and Medocinia are from the early to middle Miocene of Europe; and Phocageneus is from the early Miocene of North America. Squalodelphinidae are medium-sized odontocetes similar in size to (to slightly smaller than) the living Tursiops. The rostrum is of moderate length and slender (Fig. 5). The teeth are more or less homodont: the posterior teeth are single rooted but they are clearly lower and more triangular than the anterior. An interesting characteristic of Squalodelphinidae is the thickening of the supraorbital region of the skull (maxilla and/or frontal) (Figs. 5b and 5d). This condition seems to foreshadow the extreme morphology observed in Platanistidae (see later and Fig. 6).

Figure 4 Reconstruction of the skull of Waipatia maerewhenua (late Oligocene, New Zealand): (a) dorsal (b) ventral, (c) lateral views.

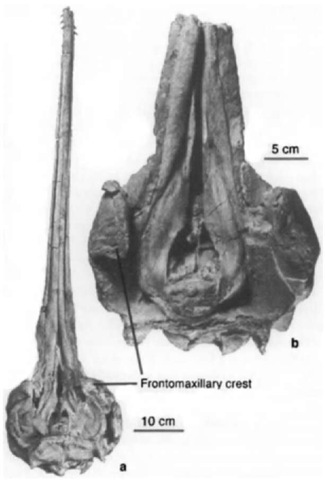

F. Platanistidae

Platanistidae are represented in the fossil record by two genera: Zarhachis and Pomatodelphis (Fig. 6). They both show all the Platanistoid synapomorphies of the ear region, palatine, and scapula. The main characteristic of Platanistidae is the development of large maxillary (Platanista) or maxillofrontal (Zarhachis, Pomatodelphis) crests, which are already incipi-ently developed in Squalodelphinidae (see earlier discussion). A peculiarity of Platanista is the fact that the palatine is entirely covered by the maxilla and the pterygoid. In Zarhachis and Pomatodelphis this condition is incipiently developed, as the palatine is partially covered (Muizon, 1987, 1994) and the visible portion of the bone is displaced laterally. Both genera have a very long and slender rostrum bearing homodont teeth. Zarhachis is slightly larger than Pomatodelphis and approaches the size of a small Mesoplodon. Allodelphis has been regarded as a platanistid; however, this genus is still too poorly known to be clearly referred to this family. It is provisionally considered to be a platanistoid, pending discovery of more complete specimens. The two undoubted fossil palatanistids, Zarhachis and Pomatodelphis, were found in a marine environment. They are from the middle Miocene of North America and Europe (Pomatodelphis only). No fossil platanistids have been found so far, neither in the Southern Hemisphere nor in Asia, and it is possible that the family had a Tethyan distribution.

Figure 5 Skulls of squalodelphinids: Squalodelphis fabianii (early Miocene, Italy) skull and mandible in dorsal view (a) and lateral view (c) (note the thickness of the supraorbital region), and reconstruction of the skull of Medocinia tetragorhina (early Miocene of France) in dorsal view (b) and lateral view (d) (from Muizon, 1988).

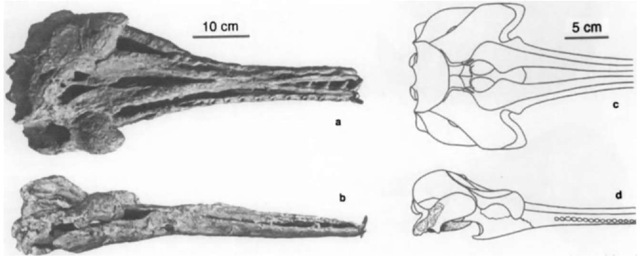

Figure 6 Skulls of Platanistidae: (a) Pomatodelphis cf. inae-qualis (middle Miocene, Maryland) skull in dorsal view and (b) Zarhachis flagellator (middle Miocene, Mari/land) skull (most of the rostrum missing) in dorsal view.

II. Nonplatanistoid "River Dolphins"

These are represented by the Recent families Lipotidae (Lipotes), Iniidae (Inia), and Pontoporiidae (Pontoporia blainvillei, the franciscana). Most authors recognize the three families, however, some authors place the three genera in the same family, Iniidae (Heyning, 1989), whereas others (Fordyce et al., 1994) recognize only two families: Pontoporiidae (Pontoporia and Lipotes) and Iniidae (Inia).

Fordyce and Muizon (2001) recognized three families because the three groups probably do not represent a mono-phyletic unit. They are included in the infraorder Delphinida on the basis of several synapomorphies (Muizon, 1988), such as the development of a lateral lamina of the palatine, the sigmoid morphology of the involucrum of the tympanic and its posterior excavation, the development of a ventral rim on the ventromedial face of the anterior process of the periotic, and the increase in size of the processus muscularis of the malleus. Lipotidae are the earliest divergent Delphinida. The other Delphinida [Inioidea (Iniidae + Pontoporiidae) and Delphi-noidea] differ from Lipotidae in the following synapomorphies: reduction of the anterior process of the periotic, which loses the bullar facet; increase in size of the processus muscularis of the malleus, which is distinctly more developed than the manubrium; and presence of a pair of ventral processes on the anterior region of the sternal manubrium (Muizon, 1988). The second diverging clade is Inioidea. The third clade, Delphinoidea, presents an apomorphic thickening of the apex of the anterior process of the periotic and a great reduction of the dorsal portion of the transverse process of the atlas. Therefore, Delphinida include three superfami-lies of odontocetes: Lipotoidea, Inoidea, and Delphinoidea (Muizon, 1988). These phylogenetic hypotheses on the nonplatanistoid “river dolphin” have been partly confirmed by Messenger and McGuire (1998).

A. Lipotoidea

This monofamilial superfamily includes two genera: Lipotes (Recent, China) and Parapontoporia (Neogene, west coast of North America). Prolipotes from the Miocene of China is based on a nondiagnostic mandible fragment and is regarded as in-certae sedis (Fordyce and Muizon, 2001).

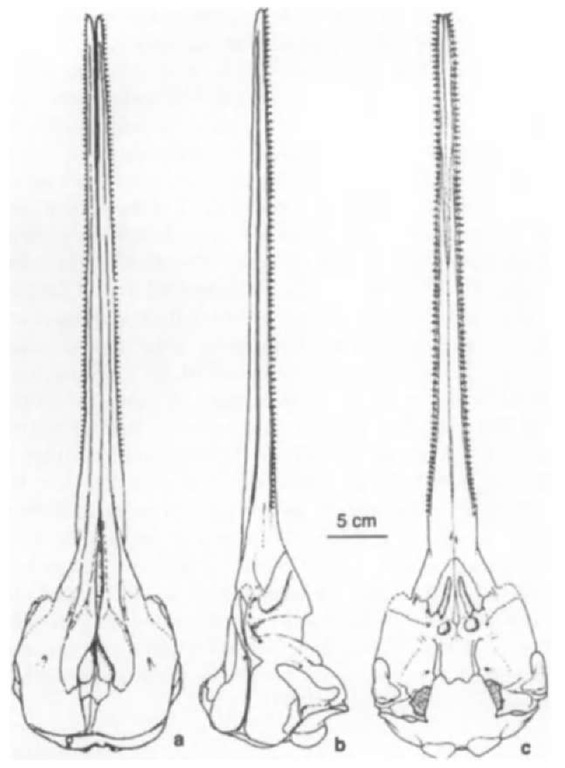

Parapontoporia (Fig. 7) is regarded here as a lipotid, although classified by its author (Barnes, 1985) in Pontoporiidae. However, as noted by Barnes (1985) and Muizon (1988), the periotic of Parapontoporia is extremely similar to that of Lipotes vexillifer, the baiji, and bears no resemblance to that of ponto-poriids. In fact, Barnes (1985) noted that Parapontoporia was more similar in many aspects of its skull to Lipotes than to Pontoporia. The skull of Parapontoporia displays a distinct narrowing at the base of the rostrum, which is always present in Lipotes and generally absent in pontoporiids (when present in Pontoporia it is weak); Parapontoporia does not bear the premaxillary eminences that are present in all pontoporiids and iniids; the nasals of Parapontoporia tend to be approximately vertical and not horizontal as in pontoporiids.

Parapontoporia is the only fossil lipotid based on good cranial material. Whereas its braincase is only slightly larger than that of Lipotes, its rostrum is almost twice as long. The asymmetry is less pronounced than in Lipotes but distinct. The teeth are small, single cusped, and numerous (ca. 80 on each side). In Lipotes the number of teeth varies from 30 to 36. Lipotids are known in the Northern Hemisphere only (China and California) and it is possible that the evolutionary history of the family took place in the North Pacific.

Figure 7 Reconstruction of the skull o/Parapontoporia stern-bergi (early Pliocene, California): dorsal (a), ventral (b), and lateral (c) views.

B. Inioidea

This superfannly includes Iniidae and Pontoporiidae. The two families share synapomorphies of the periotic (great reduction of die anterior and posterior processes), malleus (unique extreme development of the processus muscularis), premaxilla (presence of premaxillary eminences), and maxilla (frontomax-illary crests: dorsal inflexion of the postorbital edges of the maxilla and frontal). The superfamily is documented by a few well-established fossil genera mostly from South America.

Iniidae are represented in the fossil record by a single genus known by relatively well-preserved cranial remains: Ischyrorhynchus. Genera Saurocetes, Plicodontinia, Hesperocetus, Hesperoinia, and Lonchodelphis, which have been related to Iniidae, are based on nondiagnostic rostra, mandible fragments, or isolated teeth. Although they could be referrable to this family, these genera should be regarded as incertae sedis pending further cranial discoveries. Goniodelphis is based on a partial skull, which probably belongs to an iniid. However, because of its incompleteness, this specimen has been only tentatively referred to the family by Fordyce and Muizon (2001).

One of the major characteristics of Iniidae (Ischyrorhynchus and Inia geoffrensis, the Amazon river dolphin or boto) is the development of a frontal hump on the vertex, which is expanded at its apex. Iniidae also present an extreme reduction of the posterior process of the periotic.

Ischyrorhynchus is approximately 30% larger than Inia and its rostrum is proportionally longer. In addition to these features, Ischyrorhynchus is very similar to the Recent iniid. It is from the late Miocene of the Parana Basin (Argentina) and, therefore, was living in a freshwater environment.

Pontoporiidae are known by two fossil genera based on well-preserved cranial remains (with associated ear bones): Pliopontos and Brachydelphis (Fig. 8). Pontistes is another pontoporiid and is based on a single partial skull widi a well-preserved vertex. Pontivaga has been referred to the ponto-poriids; however, this genus, which is based on a partial mandible, is regarded as incertae sedis.

Pontoporiidae share synapomorphies such as a low vertex with flat subhorizontal nasals and the posterior extension of the posterior process of the periotic, which becomes blade-like.

Pliopontos is 50% larger than Pontoporia. As in the recent taxon, the rostrum is long and slender with sharp small teeth. Except for its size, Pliopontos is very similar to Pontoporia. It is from the early Pliocene of Peru and was marine. Brachydelphis is a much less classical pontoporiid. It has a very short rostrum, which is as long as the braincase. The latter is much larger than in Pontoporia and is similar in size to that of Pliopontos. Because of these unique features for a pontoporiid, Brachydelphis has been placed in its own subfamily, the Brachy-delphinae. It is from the middle Miocene of Peru and lived in a marine environment.

III. Conclusions

There is now a consensus that odontocete taxa which were traditionally placed in the “river dolphins” (the “Platanistoidea” of Simpson 1945) belong to two different groups of dolphins: Platanistoidea, which are an early divergent superfamily of odontocetes, and Inioidea and Lipotoidea, which are included in Delphinida (Lipotoidea + Inioidea + Delphinoidea). Platanistoidea represent the sister group of a clade which includes Delphinida and the fossil superfamily Eurhinodelphinoidea (Fig. 1). Therefore, the “river dolphins” represent a polyphyletic group. They are paraphyletic if only Recent taxa are taken into account. Even the nonplatanistoid “river dolphins” do not represent a monophyletic grouping. Fossil platanistoids are diverse and distributed into several families. Fossil lipotids and inioids are still relatively scarce but can be easily related to one of the three non-platanistoid families of “river dolphins.”

As stated earlier, most fossil “river dolphins” are from a marine environment and adaptation to fresh water is a convergence in at least in three groups: Platanistidae, Lipotidae, and Inioidea. Adaptation to this environment also appeared independently in two delphinoids (Orcaella and Sotalia). It therefore appears necessary to avoid the use of the term “river dolphins,” an ecological grouping which is not monophyletic, especially when fossil taxa are considered.

Figure 8 Skulls of Pontoporiidae: Pliopontos littoralis (early Pliocene, Peru) reconstruction of the skull in ventral (a), dorsal (b), and lateral (c) views (from Muizon, 1984); and Brachydelphys mazeasi (middle Miocene, Peru) reconstruction of the skull in ventral (d), dorsal (e), and lateral (f) views.

![Skulls of Squalodontidae: (a) Eosqualodon langewi-eschei (late Oligocene, Germany), reconstruction of the skull in dorsal view [from Rothausen (1968), modified]; (b) Squalodon bellunensis (early Miocene, Italy), reconstruction of the skull in dorsal view [from Rothausen (1968), modified; (c) S. bellunensis (early Miocene, Italy), skull and mandible in lateral view; (d) Squalodon bariensis (early Miocene, France), skull (apex of the rostrum missing) in ventral view, a and b are reproduced with permission of Paliiontologische Zeitschrift. Skulls of Squalodontidae: (a) Eosqualodon langewi-eschei (late Oligocene, Germany), reconstruction of the skull in dorsal view [from Rothausen (1968), modified]; (b) Squalodon bellunensis (early Miocene, Italy), reconstruction of the skull in dorsal view [from Rothausen (1968), modified; (c) S. bellunensis (early Miocene, Italy), skull and mandible in lateral view; (d) Squalodon bariensis (early Miocene, France), skull (apex of the rostrum missing) in ventral view, a and b are reproduced with permission of Paliiontologische Zeitschrift.](http://lh6.ggpht.com/_NNjxeW9ewEc/TNGgvbxbz-I/AAAAAAAAPjM/CkKo3UMW_no/tmp1DF47_thumb_thumb1.jpg?imgmax=800)