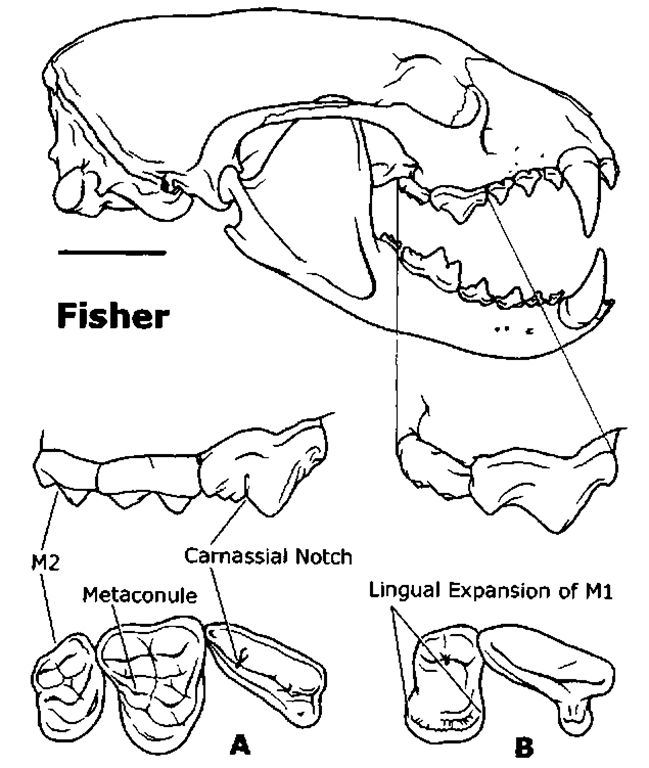

Mustelidae is one of the most successful families of the 5 order Carnivora; its 23 genera and 65 extant species , . of weasels, badgers, otters, and skunks have a nearly worldwide distribution. These small to medium-sized mammals tend to have long and slender bodies, exhibit sexual dimorphism (males are generally 25% larger than females), and possess well-developed anal scent glands. Several cranial and dental characters, including flooring of the suprameatal fossa (an expansion into the roof of the auditory canal), reduction/loss of the upper second molar (M2), reduction/loss of the meta-conule and lingual expansion of the upper first molar (Ml), and loss of the carnassial notch on the last upper premolar (P4), have been argued to be synapomorphies of a monophyletic Mustelidae (Fig. 1). Recent molecular analyses, however, suggest that skunks are distantly related to other mustelids and occupy a phylogenetic position as sister taxon to Musteloidea, a clade consisting of Mustelidae (minus skunks) and Procyonidae (raccoons and their relatives).

I. Palaeomusteloids, Early Eumustelids, and Origins of Lutrinae

The earliest mustelid-like fossils are assigned to Mustelavus from the late Eocene of western North America and Mustelic-tis and Plesictis from the early Oligocene of France. Because these animals retain upper and lower second molars and an upper carnassial notch, they are conservatively placed in an undifferentiated musteloid stem group. Others have argued, however, that the small size of the second molars and reduction of the metaconule are indicative of mustelid affinities and place all three genera in the family Mustelidae (Baskin, 1998). An increased diversity of palaeomusteloids occurred in the late Oligocene-early Miocene of North America and Europe, and although most of these taxa have little to do with later mustelid evolution, two European genera, Paragale and Plesiogale, lose the carnassial notch, exhibit some flooring of the suprameatal fossa, and show rudimentary lingual expansion of the upper first molar suggesting an ancestral relationship to eumustelids (Hunt, 1996). Although eumustelids evolved in Eurasia, the earliest representatives of this group are found in the early Miocene of North America, suggesting a late Oligocene immigration event, with immigration events into Africa and South America occurring in the early Miocene and late Pliocene, respectively. By the late Miocene there is considerable mustelid diversity in the fossil record and all of the extant mustelid subfamilies are represented.

Figure 1 Characteristics of upper carnassial (P4) and molar (Ml) teeth in mustelids. The dentitions of a canid (gray fox, A) and mustelid (fisher, B) are compared in lateral (top) and occlusal views (bottom). Eumustelids have lost the second molar, the metaconule on Ml and the carnassial notch on P4, and expanded the lingual surface of Ml. Scale bar = 2 cm.

One enigmatic taxon that has been included with the palaeomusteloids by some workers and as an incertae sedis member of Arctoidea [Musteloidea + Ursidae (bears) + Pinnipedia] by others is the late Oligocene Potamotherium, Known from a number of complete and well-preserved skeletons, this aquati-cally adapted otter-like genus exhibits a combination of musteloid and pinniped characters that have suggested to some that it may be transitional between mustelids and phocids (Tedford, 1976). although others have argued that these morphological similarities are convergent. The earliest widely accepted fossil otter is the early to mid-Miocene genus Mio-nictis known from dental remains in North America, Europe, and China. Diversification of the major lutrine clades likely occurred by the mid-Miocene (Koepfli and Wayne, 1998), although fossil records for most lineages tend to be Plio-Pleistocene in age. One exception to this is the fossil record of the sea otter (Enhydra lutris), the most marine and one of the most morphologically derived of all otters. Remains of Enhy-dritherium and Enhydriodon, the consecutive outgroups to

Enhydra, respectively, have been described from throughout the late Miocene, sharing with the living sea otter loss of upper and lower first premolars, a short robust jaw, and lower first molars with low, inflated cusps (Berta and Morgan. 1985).

II. Phylogenetic Relationships of Musteloids

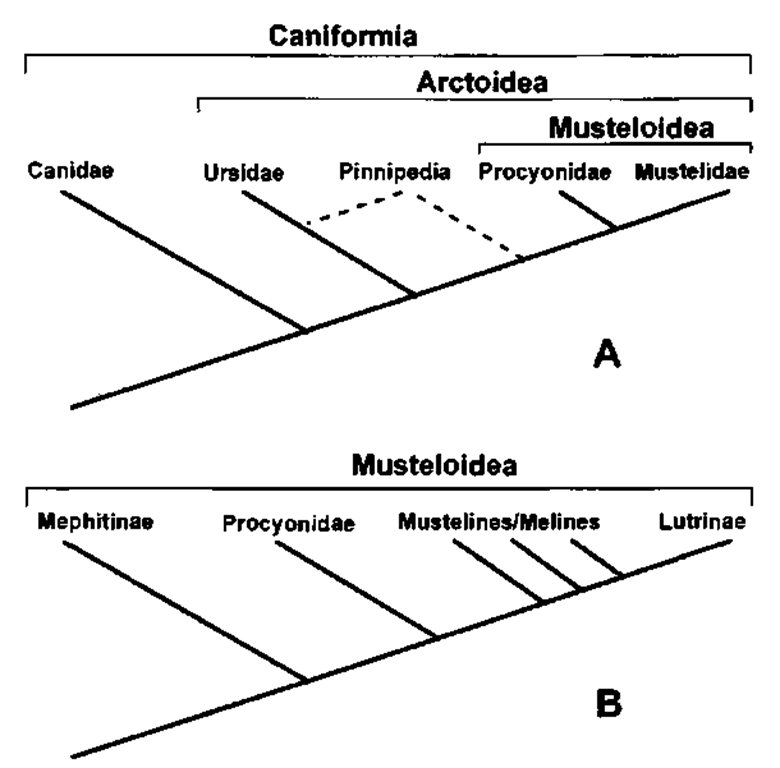

A number of recent morphologic and molecular analyses have addressed phylogenetic relationships both among genera that have been referred to Mustelidae and between mustelids and other extant members of the monophyletic suborder Can-iformia, which includes canids (dogs), procyonids. pinnipeds, and ursids. While most of these analyses have supported a traditionally held view that Procyonidae and Mustelidae are sister taxa, and that Ursidae and Canidae represent successive out-groups (Flynn et al., 1988), the position of Pinnipedia has proven more difficult to resolve, with morphological evidence supporting a sister taxon relationship to Ursidae and molecular data tending to support a sister group relationship to Musteloidea (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2 Cladograms depicting the relationship of mustelids to other extant members of the carnivoran suborder Caniformia (A) and one hypothesis of phylogenetic relationships among musteloids based on molecular data where skunks (Mephitinae) are not part of a monophyletic Mustelidae. Dotted lines (A) show alternative hypotheses for pinniped relationships, and the musteline/meline designation (B) is used to indicate the para-phyletic nature of these subfamilies.

Among the 23 genera and five subfamilies attributed to Mustelidae, there is strong support, both molecular and morphologic, for the monophyly of otters (Lutrinae) and skunks (Mephitinae), little support for Mustelinae monophyly, and no support for badger (Melinae) monophyly (weasels, martens, wolverines, among others). Lutrinae appears to be nested well within the mustelid clade (Fig. 2B). and several studies have suggested that skunks are the sister taxon to otters (Wyss and Flynn, 1993). Ribosomal protein sequence data (Dragoo and Honeycutt. 1997), however, argue for a phylogenetic position of skunks as sister taxon to Musteloidea (Fig. 2B). implying that characters such as loss of the second molars and upper carnas-sial notch evolved more than once among musteloids. Consensus on musteloid phylogeny will require more analyses that combine molecular and morphologic data, and that include important fossil taxa such as Mustelavus and Potamotherium. as well as the early procyonid Amphictis.