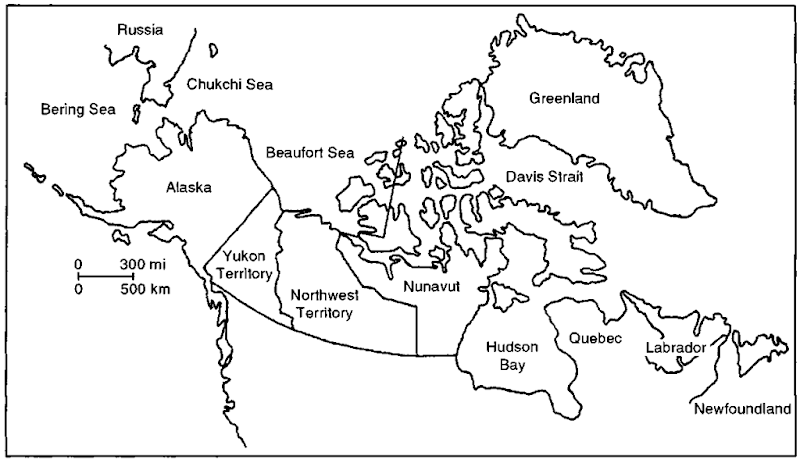

Inuit is a northern Alaskan term meaning “people” that has come to include the native “Eskimo” peoples of Chukotka, northern Alaska, Canada, and Greenland (Fig. 1). Inuit represent one extreme of the hunter-gatherer paradigm, relying almost exclusively on hunting to thrive in one of Earths harshest environments, the Arctic. Most Inuit hunting has focused on marine mammals, with the bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus) making up a central part of the harvest. Whaling was important to Inuit from Alaska to Greenland and underwrote the formation and survival of permanent sedentary villages on Alaska’s arctic coast.

Figure 1 Coastal Arctic inhabited the Inuit.

Inuit have depended on hunting marine mammals and caribou for thousands of years. The Birnirk culture (a.d. 400-800) was the first to successfully incorporate whale hunting into their subsistence regime. Whaling was completely integrated into the succeeding Thule culture starting around a.d. 800. Around a.d. 1000, Thule folk and their whaling culture spread out of Alaska and into Canada and Greenland.

The ancestral Inuit tool kit employed raw materials from hunted species plus some worked stone and driftwood. Their technology depended heavily on compound tools made from several types of raw materials and incorporating several parts. A harpoon might employ a driftwood shaft, a foreshaft made from caribou antler, a socket piece from walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) bone, a finger rest made from walrus ivory, lashings made from caribou sinew, a head made from whale bone, a blade made from slate, a line made from walrus hide, and a sealskin float.

The harpoon head toggled, or turned, 90° once it was thrust into the animal, preventing withdrawal. As the head toggled, the shaft fell away, leaving a hide cord running from the head back to the hunter or to a float. The float was a sealskin with all but one of its orifices sewn shut. The remaining orifice was used to inflate the float through an ivory inflation nozzle, which was then plugged with a piece of driftwood. The float marked the prey’s location and slowed it down, tiring it as it attempted to swim or dive.

The first commercial whalers to enter the northern sea near Greenland in the 14th century found Inuit hunting bowhead whales from umiat (skin-covered driftwood framed boats), using compound harpoons with toggling heads. By die early 17th century, Greenlandie Inuit were severely impacted by commercial whaling, which decimated the whale stocks, perhaps even eliminating the Svalbard stock upon which the east Greenlanders seem to have depended. In Canada, much commercial whaling for the European trade came to be shore based and carried out by local Inuit crews, entailing major alterations to Inuit lifestyles compounded by the destruction of the whale stocks.

Westerners first reached northern Alaska in 1826. However, Inuit lifestyles there were relatively unaltered by contact with the West until the second half of the century, when depredation of the bowhead whale stocks by commercial whaling and the spread of European diseases had disastrous consequences for the Inuit.

Inuit clothing was superior to Western cold weather gear and was often sought by Yankee whalers in Alaskan waters. Entire Inuit families were often hired to travel aboard commercial whaling ships in the Arctic; women skin sewers made and mended clothing for the crew while the men hunted with the Yankees. By the late 19th century, Yankee whalers also adopted the Inuit toggling harpoon head (Bockstoce, 1986).

The Inuit diet relied upon meat and blubber from whales, seals, and polar bears (Ursns maritimus). Caribou meat was eaten with seal oil or whale oil. Inland Inuit relied upon traded seal oil for a critical part of their dietary intake (Sheehan, 1997). Skins for boats came from seals and walruses. These, along with caribou and birds, also provided skins for clothing. Whale and seal oil provided fuel for lamps, the only source of heat other than body heat in houses.

In Alaska, driftwood seinisubterranean houses incorporated long entrance tunnels made up of whale bones, while in areas of Canada and Greenland, where driftwood was scarce, even the houses were constructed with whale bones, or with stone and bone. The only prehistoric qargi. or whalers’ ceremonial house, that has been excavated in north Alaska was made almost entirely of whale bones.

Pokes (seal skins) filled with seal oil were used to preserve meat. Prehistorically in Alaska, i.e., prior to 1826 and even past the middle of the 19th century, seal oil and whale oil pokes were major trade items from coastal areas (Maguire, 1988). Return trade from inland Inuit was primarily caribou skins for clothing and blankets. The economy left nothing to waste, with dog teams consuming old clothing as well as any of the harvest not used directly by the Inuit.

Whaling provided a dependable food surplus to the prehistoric coastal Alaskan communities, allowing them to organize their lives around the whale hunt (Sheehan, 1997). This whaling culture was successful for a thousand years. Whaling remains the organizing focus of Inuit life todav in northern Alaska and is still an important part of Inuit ideology in other parts of the Arctic. Marine mammal hunting continues to underpin Inuit subsistence activities and social interactions.

I. Precontact Whaling

It is commonly believed that indigenous whaling developed in the Bering Sea and Bering Strait region about 2000 years ago with the Okvik and Old Bering Sea cultures. An increase in the diversity and complexity of tools used for hunting marine mammals took place from approximately 100 b.c. to a.d. 600. This suggests an increased dependence on large whales and other marine mammals (Stoker and Krupnik, 1993). There appear to be two significant differences between the early groups that hunted whales but did not rely upon them and later groups that were dependent for their survival on the whale hunt. One of these differences was technological, the other social.

The introduction of drag float technology may have transformed whale hunting from a “status” activity resulting, when lucky, in a “windfall,” into a “normal” activity resulting in a regular and substantial payoff. Transformation of the umialik (whaling captain) from a temporary hunt leader into a permanent political leader responsible for distributing the whaling surplus throughout the community allowed the population to thrive and grow. The combination of technological and social change culminated in the period of the Punuk and Thule cultures starting at a.d. 800.

Although it is generally agreed that widespread large whale hunting did not occur until the Thule culture spread across North America to Greenland, whaling may have developed independently in several areas at different times. The earliest of these may be the Maritime Archaic tradition of Labrador and Newfoundland, dating from approximately 3000 b.c. The Maritime Archaic is believed to be one of the earliest cultures to use the toggling harpoon head. M0bjerg (1999) reported that the Saqqaq culture of Greenland’s west coast, part of a broader Arctic small tool tradition, which stretches across the North American Arctic, may have been hunting baleen whales as early as 1600-1400 b.c. One of the most interesting cases is the old whaling culture of Cape Kruzenstern, near Kotzebue Sound in Alaska, which appeared suddenly around 1800 b.c. but disappeared shortly thereafter. These people used large lance and harpoon points, possibly to hunt for baleen whales. The abundance of whale bones in the area suggests that whaling was practiced, but there is no evidence that the technology was passed to later cultures (Giddings. 1967).

The Thule whaling culture developed in northwestern Alaska around a.d. 800 and spread very quickly across arctic Alaska and Canada as far as Labrador and Greenland within a few hundred years. The rapid spread of the Thule whaling culture was perhaps influenced by a period of climatic warming. The warmer weather may have resulted in seasonally open water across the entire coast from northwest Alaska to eastern Canada and Greenland, making Pacific and Atlantic populations of whales contiguous and more numerous. These conditions would encourage the expansion of a shore-based whaling culture.

The climate of the far north did not remain warm and stable for long. Colder weather and a resulting increase in expanse and duration of ice cover reduced the distribution and numbers of whales in the Arctic, with a concomitant reduction in the geographic range that could sustain a whaling-focused economy, and made reliance on whales riskv in areas that were more marginal. Thule people who could no longer succeed in whaling focused more heavily on smaller marine mammals and other small game. Some parts of the central Canadian Arctic were depopulated.

The climatic variations resulted in dramatic changes to the Thule whaling culture throughout its range. The remnant Thule cultures gave rise to the contemporary Inuit cultures of pre-sent-dav Canada, Greenland, and Alaska. In Alaska, whalers were able to continue their primary reliance on whale hunting by clustering in large permanent villages at points of land, where every spring they could rely on currents and geography to place them within walking distance of nearshore leads in the ice. Whales followed the leads as they went north for the summer. The leads became the foci of the whale harvest, supplemented by fall whaling in open water, as the whales passed the points on their vvav south.

II. Mysticetes

A. Bowhead Whale, agviq

The bowhead whale is the largest animal hunted by any prehistoric or historic hunter-gatherer society. Adults reach at least 20 m and weigh 50,000 kg or more. The slow moving, blubber-rich whale is a particularly suitable target, as it often travels close to shore in predictable migration patterns.

The advent of commercial whaling and the consequential contact with Europeans forever changed the patterns of indigenous bowhead whaling. Commercial whalers reduced bowhead populations to levels too low to support a subsistence hunt in most of the whales’ range. The Chukotkan natives continued bowhead whaling until the late 1960s when Soviet authorities replaced the shore-based hunt with a catcher-based hunt, primarily for grav whales (Eschrichtius robustus). In 1997, the International Whaling Commission (IWC) allotted a quota of five bowheads to Chukotkan natives. With assistance and training by Alaskan whalers, the Chukotkan Inuit have begun to hunt bowhead whales again. One whale was landed in 1997 and another in 1998. The Canadian Inuit ceased traditional bowhead hunting around World War I due to low whale numbers and active discouragement by the Canadian government. In 1991, the Canadian Inuit at Aklavik, in the Mackenzie River delta, landed a bowhead for the first time since the early 20th century. An unsuccessful hunt was carried out in 1994 and a successful hunt in 1996. Greenlandic Inuit hunted bowheads for many centuries before commercial whaling depleted the Atlantic stocks nearly to extinction. Greenlandic Inuit were employed by Danish commercial whalers from the late 18th century until 1851, when depleted bowhead numbers brought a halt to commercial hunts. Currently the bowhead whale is hunted under the quota system in northern Alaska, in the villages of Savoonga, Gambell, Little Diomede, Wales, Kivalina, Point Hope, Wainwright, Barrow, Nuiqsut, and Kaktovik, along the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort Seas.

After commercial whaling ceased in the early 20th century, Alaskan Inuit returned to a strictly subsistence bowhead hunt. Bockstoce (1986) estimated that an average of 15-20 whales were landed each year from 1914 to 1980. After 1970 there was a significant increase in the number of bowheads landed in Alaska. This was a result of a combination of factors. There was an increase in cultural awareness by Native Americans in general and Alaska Natives in particular, brought about by the passage of the Alaska Native Lands Claim Settlement Act in 1971. The discovery of oil in Prudhoe Bay in 1968 and the construction of the Trans-Alaska pipeline provided significant cash input into the economy of northern Alaska, which prompted a large increase in the number of whaling captains. The position of whaling captain in northern Alaskan Inuit whaling communities has always been one of great respect and authority. Traditionally, only those hunters who demonstrated great hunting success and respect for customs rose to the position of whaling captain. The expense of obtaining whaling gear limited the number of crews and ensured that only experienced whalers rose to the position of captain. The influx of money and employment in the 1970s resulted in a doubling of the whaling crews in northern Alaska from 44 in 1970 to 100 in 1977. The number of whales landed also increased from an average of 15/year to about 30/year from 1970 to 1977. There was also a large increase in the number of whales struck but lost and presumably killed.

The increase in the number of struck but lost whales, combined with an estimate from the IWC that only 600-2000 bowheads remained in the Arctic, prompted the IWC to call for a total ban on bowhead whaling. The Inuit reacted strongly to this ban. They formed the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission (AEWC), composed of whaling captains from each whaling village. In 1978 the AEWC, through the U.S. delegation to the IWC, negotiated a quota of 12 bowheads landed or 18 struck for the 9 Alaskan whaling villages. Since then the IWC has established quotas for Alaskan whalers, and the AEWC has distributed strikes to the 10 Alaskan whaling villages (Little Diomede joined AEWC in 1992). Research paid for and con

ducted through the AEWC and the North Slope Borough (NSB, the regional government in northern Alaska) Department of Wildlife Management indicates that the Eskimo whaling captains were correct when they asserted that there were many more whales than the IWC estimated. Careful censuses of the Bering-Chukchi-Beaufort Seas bowhead population have shown that the bowhead population in the western Arctic actually numbers around 8000 and is increasing about 3% per year. In consequence, the number of strikes allotted to Alaskan whalers has also increased. In 1997, a block quota was set for the years 1998-2002. The quota of 280 whales to be landed during that period includes five whales to be taken per year in Chukotka.

Alaskan Inuit hunt bowhead during the spring and fall migration. In spring, bowheads migrate from wintering grounds in the Bering Sea north through the Bering Strait to feeding areas in the eastern Beaufort Sea. The whales move along open leads in the ice created when drifting pack ice shears away from the grounded, shore-fast ice. These leads occur in predictable places along the Alaskan coast. Bowheads begin the migration north from the Bering Sea in late March through early April and pass the whaling villages of Gambel and Savoonga soon thereafter. The whales pass by Pt. Barrow from mid-April to early June and arrive in the eastern Beaufort Sea in May. Bowheads begin the fall migration across the central Beaufort Sea in early September and pass Alaska’s north coast from mid-September to early October. Some whales may continue across the northern Chukchi Sea arriving in Chukotka in November, and others may move southward, likely crossing the central Chukchi Sea.

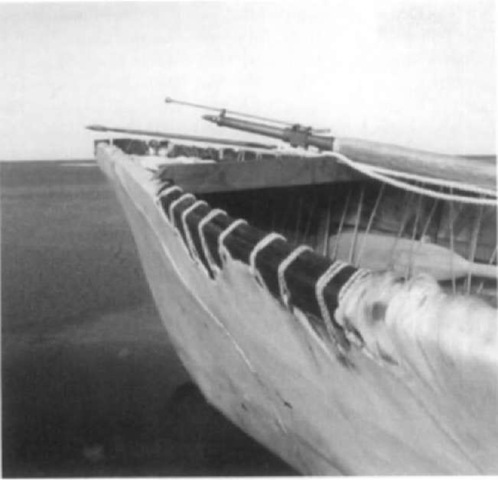

Equipment used in the modern whale hunt is a combination of precontact technology and tools adopted from Yankee whalers. The boat used for the hunt is a skin-covered frame called an umiaq. The frame was traditionally made of driftwood lashed with baleen with some whale bone fittings, but now is made from prepared lumber. The cover is made from the skins of bearded seals or walrus hunted the previous summer. The skins are left to ferment, which softens the skin and allows the hair to be stripped off easily. The skins are sewn together using a special waterproof stitch and stretched over the frame using rawhide thongs or, more recently, jute or nylon line. The average umiaq in Barrow (Fig. 2) requires six bearded seal skins for the cover, is 6.5-8.5 in long, 1.5-1.8 m across the beam, and weighs approximately 160 kg when dry (Stroker and Krupnik, 1993). The skins are usually replaced every 1 or 2 years, depending on their condition. In some places, aluminum or wooden boats powered with outboard motors have replaced the umiat (plural of umiaq). However, in areas where heavy ice is often encountered, umiat are still used because they are easier to move across and through heavy ice. During fall whaling in Barrow, Nuiqsut, and Kaktovik and during spring whaling in areas where leads are wide and whales travel farther from the lead edge, aluminum or fiberglass boats powered with outboard motors are used.

Weapons used for hunting are essentially the same equipment used by commercial whalers at the end of the 19th century. The darting gun and shoulder guns were introduced by Yankee whalers soon after the Civil War and were adopted by

Figure 2 Umiaq (skin boat) and harpoon used by Eskimo whalers in Barrow, Alaska.

Inupiat hunters in the last decades of the 19th century (Bock-stoce, 1986). The harpoon consists of a wooden shaft 1.5-2 m long tipped with a detachable steel harpoon with a brass toggling head attached to a float with 55 m of strong nylon line. The harpoon is tipped with a plunger trigger-driven gun that fires an 8-gauge, brass bomb simultaneously with the harpoon strike. A second darting gun that resembles the harpoon but without the toggling head harpoon is used to deliver a second bomb. Heavy brass shoulder guns are also used to fire bombs from distances greater than can be attempted with the darting gun. The brass-encased bombs are charged with penthrite. which replaced black powder in 1998. Penthrite bombs deliver a sudden concussion and kill by shock rather than laceration and tissue damage. This reduces the number of whales that are struck but lost. Other equipment includes flensing tools hand made of steel blades (often from hand saws) attached to long wooden handles, heavy-duty block and tackle to haul the whale onto the sea ice. an aluminum or fiberglass boat used to chase and retrieve a whale after a strike is made from the umiaq, and snowmobiles used to tow equipment to and from camp and to carry meat and maktak back to the village.

Preparations for whaling begin well before the whales arrive. Male members of the crew clean weapons and the ice cellar for storing meat and build sleds and other equipment needed for the camp on the ice. The wives of the captain and crew members sew a new skin cover for the umiaq frame. When the skins are dry, the umiaq is lashed to a sled for the wait until a lead opens.

Sometime before the arrival of the first bowheads the captain will decide where to place his camp. One or several “roads” are built across the ice to the selected sites. The roads are built to smooth the route across the maze of pressure ridges on the ocean ice. Smoothing the route eases the task of hauling sled loads of meat and maktak in the event of a successful hunt and provides a quick escape route if ice conditions become unsafe. Stakes with colors or symbols are often placed along the roads. Camps are located on the ice edge, often in “bays” in anticipation of whales swimming under projecting points and surfacing in those bays, or on points that provide good views of approaching whales.

Inuit believed, and many continue to believe, that whales give themselves willingly to hunters worthy of their sacrifice. Traditionally, many taboos governed activities in whaling camps, and these taboos were strictly followed to ensure a successful hunt. Tents, sleeping gear, and cooking were prohibited in camps. Most taboos have been dispensed with, but traditions still govern activity in camps. One tent is set up in camp to allow crew members to sleep in short shifts and for cooking meals. The tent is placed away from the lead and to the right of the boat to prevent approaching whales from seeing the camp. The umiaq is kept ready at the water’s edge with a smooth ramp cut into the edge so that it can be launched silently. The harpoon and darting gun are positioned in the bow of the umiaq with the line from the harpoon neatly coiled on the bow. The weapons, lines, and floats are always kept on the right side of the boat, and the strike is always made over the right side of the boat to prevent entanglement in the line. At least one crew member remains on watch at all times, scanning the lead for any sign of an approaching whale.

When a whale comes within range and is determined suitable. the umiaq is launched silently with the harpooner ready in the bow. Two to five paddlers are situated along each side of the umiaq, with a steersman in the stern to steer the umiaq toward the whale. The umiaq is paddled silently, with all crew members stroking in unison. The steersman directs the umiaq to where he or the captain hopes the whale will surface next. The harpooner strikes the whale from as close as possible, often from point-blank range. The preferred target is the post-cranial depression just forward of the back. A hit here will often kill the whale instantly. If this target is not available, the spine, heart, or kidney regions are targeted. As soon as the whale is struck, the float is thrown overboard on the starboard (right) side. If possible, a senior crew member other than the harpooner will fire the shoulder gun to plant another bomb into the whale. Other crews, alerted by VHF radio, quickly converge on the site of the strike in aluminum boats powered by outboard motors and may fire another bomb into the whale in an attempt to kill it quickly. Aluminum boats are much faster than umiat and help ensure that a struck whale will not be lost.

Immediately after the whale is killed the captain of the crew that first struck the whale says a prayer (to the Christian God). The prayer is often broadcast over VHF radio and is the first signal of a successful hunt to villagers waiting on shore. The whale’s pectoral flippers are then lashed together and the flukes may be removed to reduce drag. A long line is attached to the caudal section forward of the flukes and all available boats attach to the line, with the successful crew at its head, to tow the whale tail first to the butchering site on the ice. Word of the successful hunt is sent to the village by snowmobile, and the whaling flag of the successful crew is raised over the captain’s home. Many members of the community then travel to the butchering site to help with hauling the whale onto the ice and butchering it.

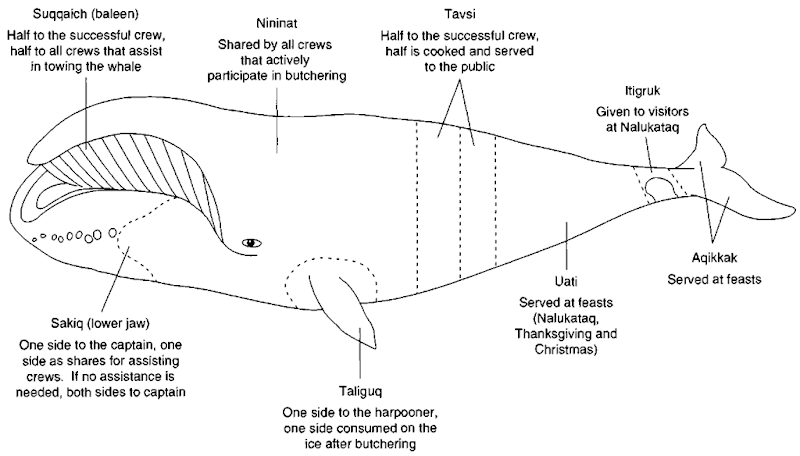

At the butchering site a large block and tackle is attached to the ice and used to haul the whale onto the ice. Eveiy available crew member and community member hauls on the free end of the line running through the block and tackle, pulling on commands from the whaling captains. If the whale is too large to haul onto the ice, some butchering may commence in the water. The tongue or skull may be removed to ease the task of hauling the carcass onto the ice. Butchering begins as quickly as possible after the whale is hauled onto the ice because the thick blubber layer retards heat loss and the meat in an unbutchered whale quickly spoils. The whale is butchered according to strict customs governing the distribution of shares (Fig. 3). Parts of the whale are reserved for the captain of the crew that struck the whale. Most of that portion will be shared with the community at feasts and festivals that occur throughout the year. Additional shares are divided among the successful crew and the crews that assisted in killing, towing the whale to the butchering site, hauling the whale onto the ice, and butchering. Individuals not representing a crew are also offered shares of meat and maktak. A group of 20-25 people can butcher an average size bowhead in 6 or 7 hr. No shares are distributed until the butchering is complete. Traditionally, following butchering some skulls were rolled into the ocean to allow the spirits of the whales to enter other bodies and again be hunted. The spirit of the whale would remember that the captain treated it well and so sacrifice itself to that captain again. Other skulls were brought ashore and placed at the beginning of the tunnels that led to the entrances of villagers’ semisubterranean homes. These symbolically placed skulls suggested that as you entered the home you also entered the world of the whale. The prehistoric qargi or whalers’ ceremonial house was built entirely of whale parts to represent a complete whale (Sheehan, 1990). Today, some skulls are not returned to the ocean but are taken ashore where they are cleaned and displayed in the village. The remainder of the skeleton is left on the ice for gulls, foxes, and polar bears.

Bowhead maktak, served boiled fresh, or raw and frozen, is the most prized food in the Arctic. Shares of meat and maktak are widely distributed among family and neighbors, often to family members living in cities who would not receive traditional foods otherwise. Meat is eaten raw and frozen, boiled, or fermented in blood. Many internal organs are also eaten. The kidney, intestines, and heart are boiled. The huge tongue of the bowhead is considered a delicacy when boiled. Baleen was traditionally used to make toboggans, for lashing of umiaq frames, for bird snares, and to make fish nets and seal nets that could easily be freed of the ice that forms on nets immediately as they are removed from the water. A simple snap of the net broke off the ice from this resilient material. Now baleen is crafted into artwork and sold.

On the da}’ following butchering, the captain of the successful crew opens his home to the community in celebration. All comers are offered food and drink. In early June the umiat of the successful whaling crews are hauled off the ice in ceremonies (apugauti). Once again, the captain supplies food and drink to all who attend. Nalukataq, the formal whaling festival, takes place in June. Each successful crew will have their own nalukataq, or several crews will hold one together. At nalukataq, the members of successful crews distribute the majority of the meat and maktak reserved for the community. The captain and crew also distribute other foods collected during the year, such as caribou meat and soup, duck soup, goose soup, and many other traditional foods. Fruit and candy are also distributed, and coffee, tea, and soft drinks are served throughout the day.

Figure 3 Division of bowhead whale shares in Barrow, Alaska.

After the food is distributed, the blanket toss begins. Skins from the successful umiaq are removed from the boat and re-sewn to form a blanket with rope handles along the edge. Community members climb onto the blanket, one at a time, and are thrown into the air by people pulling on the handles in unison. The objective is to jump as high and as many times as possible without falling. Members of successful crews will often climb onto the blanket with bags of candy to fling to the crowd while jumping. After the blanket toss a traditional dance is usually held in the community center. Each successful crew and their families will dance by themselves, but most dances are open to anyone. Nalukataq is one of the most joyful times in the village, and the traditional dance that is the culmination of nalukataq can last late into the night.

B. Gray Whale (Eschrichtius robustus)

Only the Chukotkan Inuit of the Russian Far East regularly hunt gray whales. Historically, Chukotkan Inuit hunted both bowhead and gray whales from shore-based stations. The traditional shore-based hunt was banned by the Soviets and replaced by a catcher boat-based hunt in 1954 (Freeman et al, 1998). As a result, the cultural traditions were lost and few people now remember traditional hunting methods. The Soviet catcher boat Zvyozdmji last hunted in 1992 (Freeman et al, 1998). After the catcher boat stopped whaling, the villagers began to hunt marine mammals again to supplement dwindling food supplies.

The return to traditional, shore-based whaling was a difficult and costly endeavor. The lack of equipment and knowledge had serious consequences in several villages. Hunters from the village and Nunlingran died in several hunting accidents, and one whaling boat from Sireniki was sunk, killing all aboard. However, the hunters from seven Chukotkan villages landed 51 gray whales in 1994 (Freeman etal, 1998). In Lorino, several experienced marine mammal hunters were able to teach younger hunters the proper use of harpoons, spears, and rifles. Hunters from Lorino landed 38 gray whales in 1994. Several other villages solicited aid from Lorino. and with training from experienced hunters began to successfully hunt gray whales. The hunt is now sanctioned and controlled by the IWC. with a quota oi 120 gray whales landed in Chukotkan villages from 1998 to 2002. Gray whale hunting has again become an important part of Chukotkan Inuit cultural and dietary lives.

Gray whale hunting is carried out in the summer when gray whales move into the Bering Sea from their wintering grounds. Whaling is conducted from shore stations using skin boats (baidara) or wooden whaling boats. The harpoon-spear is a special whaling implement traditionally used by the Inuit of Chukotka (Freeman et al, 1998), consisting of a wooden shaft with a detachable metal spear that is attached to a line with a small float. Each boat carries 7 to 10 of the metal spears and one wooden shaft. The spear is thrown by hand and the metal spear detaches from the wooden shaft. The wooden shaft is retrieved from the water, fitted with another harpoon-spear, and the whale is approached again. The harpooner aims for the back of the whale, trying to hit the main blood vessels or vital organs. Once harpoons have been set, the whales are shot with large-caliber rifles. This form of hunting is often dangerous. Gray whales are known to fight aggressively. Two boats are used to ensure the hunters’ safety. The hunters also try to take small or medium sized whales.

Gray whales are taken for their meat and blubber. The meat and maktak are eaten frozen, thawed and raw, or boiled. Oil is rendered from the blubber and used as food by itself or added to edible roots, willow leaves, and other vegetables.

In northern Alaska during the early historic period, commercial trade for baleen from bowhead whales created wealth that allowed people to increase the number of dogs in their teams. As a consequence, some gray whales were hunted primarily to feed sled dogs, although some hunters also found the meat to be very tasty. Gray whales are no longer hunted in Alaska.

C. Humpback Whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) and Fin Whales (Balaenoptera phtjsalus)

Greenlandic Inuit hunted humpback whales from skin boats in much the same way they hunted bowhead whales. Humpback whales are slow-swimming whales, and the techniques used for bowhead whales were successful for humpbacks as well. Although Greenlandic bowhead hunting ceased in the mid 19th century, humpback whaling continued until the 1980s.

In the 1920s, changing sea ice conditions caused food shortages among the Greenlandic Inuit who could no longer catch seals or humpback whales using traditional means. The Danish government operated a steel catcher boat, the Sonja, with a Danish crew from 1924 to 1949. The Sonja was able to catch larger and faster-swimming whales. In 1927 the Sonja caught 22 fin whales, 9 humpbacks, 7 blue whales, and 2 sperm whales. The meat was provided to Inuit of western Greenland and the blubber was shipped to Denmark, where it was rendered to oil and sold. In 1950, the Sonja was replaced with the larger Sonja Kaligtoq. From 1954 onward, the whales were taken to a single flensing station where meat and maktak were frozen for distribution and sale throughout Greenland. In addition to the government catcher boats, in 1948 some local fishermen began installing harpoon cannons on their boats and hunting whales. Fin and humpback whales were taken to the community where meat and maktak were sold. In the late 1980s the IWC eliminated the humpback whale quota, so fin and minke whales are currently the only baleen whales that are hunted in Greenland.

D. Minke Whales (.Balaenoptera acutorostrata)

Minke whales have been hunted in Greenland since 1948. The minke whale hunt is now controlled by quotas set by the IWC and administered by the Greenland Home Rule Authority. The variable quotas consider the socioeconomic, cultural, and nutritional needs of the people and the regional abundance of whales. In the 1990s the quota varied from 110 to 175 per year. Minkes are hunted in summer and fall when ice conditions permit.

Hunts from fishing boats and small skiffs are opportunistic. Hunts take place from fishing boats whenever whales are sighted or from skiffs when enough small boat hunters are available. Whalers on fishing boats use deck-mounted harpoon cannons, whereas those aboard skiffs use hand-thrown harpoons and rifles. In each case the whales are towed back to the community for flensing and distribution. Shares are distributed to the vessel owner and crew members, and a large share is reserved for the boat. Little personal share of meat or maktak is sold, but the boat share is sold to contribute to the cost of operating a commercial fishing boat. In the small skiff hunt, shares are divided equally among the participants of the hunt and those helping with the flensing.

III. Odontocetes

A. Beluga Whales (Delphinapterus leucas)

Beluga whales are hunted across their range in Chukotka, Alaska, Canada, and Greenland. Ancestors to the modern Inuit were involved in beluga hunting as early as 5500 years ago in Alaska (Freeman et al, 1998). The techniques used by the ancestral Inuit are the same as those used in Alaska, Canada, and Greenland before contact with commercial whalers. Entire communities were involved in a collective whale hunt or drive. A shaman typically guided the hunt, which was led by a distinguished hunter from one of the communities involved. Freeman et al (1998) quoted an elder from Escholtz Bay, Alaska, describing a traditional drive from around 1870: “They made a line and moved together. They hollered, splashed their paddles, waved their harpoons to scare them into real shallow water. . . . When a hunter got a beluga, he ties it to his qayaq (kayak) and brought it to shore; if he get two, he’d tie one on each side. . . . If wind came up while men were out hunting, women would take umiaqs (skin boats) off the racks and go to help those hunters who were towing two belugas. People always helped together when they landed and pulled those beluga on the shore.” Friesen and Arnold (1995) determined that beluga whales were a focal resource for precontact Inuit of the Mackenzie delta, constituting up to 66% of their meat. Two or more hunters would cooperate in a beluga hunt. The whales were approached by hunters in kayaks who threw harpoons attached to sealskin floats. After the whale tired, it was lanced in the heart with a blade attached to one end of the kayak paddle. In some locations, hunters in kayaks working cooperatively would drive belugas into shallow water where they were killed. In northern Greenland, and possibly elsewhere, belugas were hunted at large cracks in the ice where the whales congregated to breathe.

In the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries, Canadian Inuit were hired by commercial whaling enterprises to hunt belugas. Skins and blubber from die belugas were shipped to European markets. The Inuit hunters kept die meat and some of the maktak and received trade goods, which often included wooden boats.

Methods changed with the introduction of rifles, fiberglass and aluminum boats, and outboard motors. Today, hunters in Alaska use one of four mediods to hunt belugas: harpooning or shooting from the ice edge in spring, shooting from motorized boats in open water, netting, or driving the whales into shallow water. Ice edge hunting occurs during the northward migration.

Sometimes concurrendy with bowhead whaling. Belugas can also be shot directly from shore if the migrating whales are close enough, as happened in Barrow in 1997. Open water hunting is common in summer and fall when the ocean is free of ice. Netting occurs at headlands where predictable movement patterns make netting practical. Shallow water drives are most common in shallow bays and estuaries, such as Pt. Lay and Wainwright, Alaska.

Sealskin kayaks were last used to hunt belugas in the 1960s in communities in northern Quebec and the Belcher Islands. Now hunters use skiffs or freighter canoes powered with outboard motors. Harpoons with detachable heads attached to floats are still used, although now floats are made from man-made materials rather than seal skins. Rifles (.222 to 30.06 caliber) are used to kill the whales after harpoons have been attached.

Belugas are the most commonly and widely taken whale species in Canada (Freeman et al, 1998). Beluga maktak is highly prized by Canadian Inuit. After a successful hunt the meat and maktak are distributed to family members and neighbors according to traditional customs. In some communities a successful hunt is announced over community radio and all community members are invited to collect a share. Because beluga maktak is so highly prized, very little of it is sold for redistribution through retail outlets in the Canadian Arctic. Beluga maktak is usually eaten raw and fresh, although some now deep-fry it. The meat is usually air dried before being eaten. In some communities, sausages are made by placing meat in sections of intestine that are lightly boiled before being dried or smoked. Beluga oil was used for lamp oil, softening skins, and cleaning and lubricating guns and other equipment.

Beluga hunting in Greenland has followed a history similar to hunting of other larger whale species. For many centuries, local hunters supplied meat and maktak to meet community needs. In colonial times, beluga blubber and oil became an important trade commodity. As a result, the Greenland Trade Department established commercial beluga drives and hired local hunters to carry out the hunt. Commercial drives continued until the 1950s when the European market for whale oil disappeared. Commercial whale drives reappeared in the 1960s when improved coastal communication and refrigeration made it possible to transport beluga meat and maktak from northern hunting communities to southern Greenland. Today, belugas are hunted with rifles (30.06 caliber to 7.62 nnn) from small boats. Typically, kayaks and motorized skiffs are used to hunt belugas, often singly or in pairs, but sometimes a larger number of small boats cooperate to hunt belugas swimming together. Meat and maktak are distributed throughout the community, including sale at the local market, and in retail stores throughout Greenland.

Beluga hunting in Russia only occurs in a few villages in Chukotka, and the numbers taken are small. Belugas in Russia are associated with the distribution of fish, especially arctic cod and arctic char. Hunting occurs opportunistically when belugas are encountered during other activities. Hunting occurs either from shore or from the ice edge. Hunters hide behind hummocks of ice and shoot the whales with rifles (7.62 or 9 mm). Meat is dried, frozen, boiled, or fried. Maktak is eaten raw, fresh, boiled, or fried. The skin is used for boot soles, belts, and lines. The oil is used with fish and salad plants. Historically, beluga oil was traded for reindeer meat and skins, although when Soviet state-run fur farms were operating the oil was sold to the farms (Freeman et al, 1998).

B. Narwhal (Monodon monoceros)

Narwhals have been hunted in Greenland and eastern Canada for centuries, and may have brought the Greenlandic Inuit in close contact with the Norse in Greenland beginning in the 10th century. Narwhal ivory was bartered among Inuit long before European contact. Narwhal tusks were highly valued by European traders in the Middle Ages, who sold the tusks in Europe mislabeled as unicorn horn, sometimes for their weight in gold. The royal throne of Denmark, made in the 15th century, is made almost entirely of naiwhal ivory. Narwhal tusks were the basis of trade between Greenlandic Inuit and Europeans from the 10th through the 19th centuries and were important to Canadian Inuit after the collapse of commercial bowhead whaling in the late 19th century. Inuit in Greenland and Canada used the tusks to create durable and functional tools, especially harpoon foreshafts.

Narwhals were hunted from kayaks either along the flow edge, in ice cracks, or in open water. Near ice, the narwhals were harpooned and hauled ashore. In open water, hunters worked together to drive the narwhals into shallow water where they were killed. Another method was to station hunters with rifles on cliffs who would shoot the whales as they swam by. Several hunters in kayaks would wait offshore and harpoon the whales once they were shot. Now, hunting in Canada takes place with small skiffs, rifles, and harpoons attached to floats. Narwhal hunting in northern Greenland is still accomplished with kayaks. Five-meter skiffs or 10- to 12-m cutters are used in southern Greenland, although occasionally narwhals are shot from shore or netted.

Maktak from narwhals is prized and is eaten fresh raw or aged. Narwhal oil was considered of higher quality than seal oil and was used in lamps for heat and light. The tusk remains the most highly prized product from narwhal. Today tusks are used for artwork or sold. Narwhal ivory sold for an average of $100 per foot (30 cm) in 1997 (Freeman et al, 1998). Narwhal meat was used to feed hunters’ dog teams.

C. Other Small Cetaceans

Small numbers of other cetaceans are taken in eastern Canada and Greenland. The principal species taken in Canada are common bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) and harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena). In Greenland, killer whales (Orcinus orca), long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melas), northern bottlenose whales (Hyperoodon ampullatus), harbor porpoise, white-beaked dolphins (Lagenorhynchus albirostris), and Atlantic white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhynchus acutus) are taken.

IV. Pinnipeds

A. Ringed Seal (Pusa hispida), natchiq, Bearded Seal (Erignathus barbatus), ugruk, and Harp Seal (Pagophilus groenlandicus)

Seals are probably the most widely distributed, abundant, and reliable food resource available to coastal Inuit populations. Ringed seals are available near shore for much of the year. Bearded seals are also important, although less abundant and less widely available than ringed seals. They are important not only for their meat, but also as a source of raw materials, particularly their hides (Jensen, 1987). Harp seals are seasonally very abundant in certain areas of Greenland and eastern Canada, and were taken when present. Ribbon seals (Histrio-phoca fasciata), Larga seals (Phoca largha), and harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) are only occasionally encountered. All of these pinnipeds are hunted in similar ways and have been combined for the following discussion.

Natchiq are ice adapted. They are hunted at breathing holes, in subnivean lairs, on drift ice, and in open water. Other seals are not as ice adapted as the natchiq. They can also be hunted on drift ice and in open water. Harbor seals and Larga seals tend to stay away from ice if it is present in significant amounts. Ugruk are common on ice pans and commonly hunted on pans or in open water. Harbor seals tend to be more common than natchiq in more southerly areas (southern Greenland, Labrador), although they have been regarded as shy and also potentially aggressive. Harp seals were generally taken from kayaks in open water or when hauled out on offshore drift ice, although they could be harpooned from shore or from the ice edge under certain circumstances.

Traditionally, natchiq were hunted at breathing holes on the ice, at pupping dens, while basking in the sun, by netting at the breathing hole, from the ice edge, or from boats in open water. Breathing-hole hunting was most common, as the ocean is ice covered for much of the year. Ringed seals carve out and maintain breathing holes in the ice throughout the winter. In flat ice the breathing holes may be visible from the surface, but often they are covered with snow, and practically invisible. Ringed seals maintain numerous breathing holes, so there was never any guarantee that a seal would visit the hole where the hunter was waiting.

Breathing-hole hunting was a difficult, cold endeavor and is no longer practiced to any great extent anywhere in the Arctic. Boas (1964) presented an excellent description of pre-rifle seal hunting methods and equipment. A hunter would first locate a breathing hole with the use of one of his sled dogs. Once the hole was found, the hunter set up his equipment around the hole. The hunter sat on an ice block with his feet resting on a piece of fur or stood on the fur with his harpoon in his hand or at his side and waited for the seal to arrive at the breathing hole. There was never any way to determine how long the hunter would have to wait. If the village needed food, it was not uncommon for hunters to wait 24 hr or longer for a seal to arrive. Now, more efficient and less strenuous methods are preferred.

When a seal arrives at a breathing hole, the first breath is a short, shallow sniff for any sign of danger. If the seal does not detect danger, the next breath will be deeper. On this second breath, the hunter thrust his haipoon straight down the hole striking the seal on the head or neck. The toggling head detached, preventing the seal from escaping. The seal was killed and the breathing hole enlarged to pull the seal through. Once rifles became available, seals were shot when they came to the hole, then immediately harpooned to prevent the seal from drifting away or sinking.

After the breeding season, seals enlarge their breathing holes located on large areas of flat ice so they can climb out and bask in the sunshine. Traditionally, Inuit had several methods for hunting seals at this time, described in detail in Nelson (1969) and Boas (1964). A hunter might simply wait near one of the holes for a seal to surface. The water within the hole pulsates when a seal arrives at its hole. When the seal broke the surface of the water, it was speared or shot. Occasionally, hunters placed lines with several hooks along the wall of a breathing hole to catch seals backing into the water after surfacing.

Another traditional seal hunting technique required great stealth and skill. The hunter emulated the behavior of a seal, sliding along the ice on Iris side, often with a piece of sealskin beneath him to reduce friction and keep his clothing dry. Often hunters would scrape the ice with seal claws attached to a piece of wood to mimick the scratching sound made by resting seals. A skilled hunter could approach very close to a seal basking in the sun. In this way hunters were often able to kill 10-15 seals in 1 day. In a variant of this method, the hunter pushed a small sled with a white shield that hid him from the seals.

Seals could also be netted at their breathing holes. Netting was done at night to prevent the seal from seeing and avoiding the net. This also reduced the hunters’ vision and exposed the hunter to many dangers. Four holes were cut around a breathing hole and the net lowered into the water to approximately 10 feet. Seals generally approach breathing holes along the surface, so they did not encounter the net. When the seals dove from the hole, they dove straight down and became entangled in the net. Seal netting was discontinued in the 1960s.

In spring, pregnant ringed seals hollow a natal den in the snow covering one of their breathing holes. Hunters again use one of their dogs to find the dens. The hunter cut a small hole in the wall of the den through which he could watch for the return of the mother seal. When the seal returned, the hunter jumped through the snow between the seal and its hole, trapping it. Prior to the introduction of rifles the seals were killed with a spear or club; later they were shot through the wall of the den.

Traditionally, ice-edge hunting was accomplished with a small harpoon that was thrown at seals swimming near the edge. A line was attached to the harpoon to retrieve struck seals. Hunters were limited by how far they could accurately throw the harpoons, usually 10-20 feet. The introduction of the rifle changed the nature of seal hunting. Hunting seals from the ice edge using rifles is easier and more efficient than breathing-hole hunting, and the range of the hunters has been increased greatly by the rifles. The increased range brought about two new inventions specifically for use in ice-edge rifle hunting: the retrieving hook (manaq or manaqtuun) and a small skin boat (umaiggaluuraq). The manaq consists of a rope up to 200 feet long, attached to a piece of wood with four hooks extruding from the sides. A float is attached to keep the hooks afloat for winter hunting (when seals float after being shot), and a sinker is attached for summer hunting to retrieve seals that sink to the bottom. Once a seal is shot, the hunter grabs his manaq to retrieve the seal from the water. The line is coiled and held in the left hand, while the right hand holds the line 3-5 feet from the hooks. The hook is thrown beyond the seal, the line is slowly drawn in until the hooks are near the seal, a sharp tug sinks the hooks into the hide, and the seal is carefully pulled to the ice edge.

The umaiggaluuraq (literally “small umiaq”) is 7-10 feet long and 36-40 inches wide (Nelson, 1969). Two bearded sealskins are used to cover a wooden frame. Once a hunter shoots a seal, he pulls the boat to the ice edge, often with the help of another hunter to prevent damage to the skins by dragging the boat. The boat is rowed to the seal with two short oars lashed to the gunwales. When the hunter reaches the seal, he tows it back to the ice edge with a small hook and line.

Open water hunting and hunting of seals basking on drift ice became most popular after the introduction of rifles. Before rifles were introduced, hunters occasionally harpooned seals from kayaks, but only in calm water. After rifles and outboard motors became readily available, several men would hunt together from a single umiaq. The hunters were often members of the same whaling crew using the captain’s boat. Seals were shot with rifles ranging from 22 to 30.06 caliber and harpooned. Now, aluminum boats have replaced skin boats, but the same methods are used. Open water hunting from aluminum boats is currently the most popular way to hunt both the ringed and the bearded seal in northern Alaska. Harpoons are still used in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta because people feel that shot seals sink too quickly. In Greenland, certain areas still forbid motorized boats in the hunt, although they may be used to travel to the hunting area.

B. Walrus, avid

Walruses are almost always associated with pack ice and are only hunted when the pack ice is close to shore. They do haul out on shore in certain locations, although this has become less common. Nelson (1969) reported that hunters in Wainwright, Alaska, only traveled offshore as far as land was still visible on the horizon. However, Spencer (1959) reported that hunters in Barrow often traveled 50 to 100 miles into the ocean to find walruses. The distances traveled are probably dependent on the proximity of the pack ice to shore and undoubtedly changed with the introduction of outboard motors.

Hunting walruses was, and remains, a collective hunt. The size of the walrus and the logistics of butchering and transporting the meat back to the village make it necessary for several hunters to work cooperatively. Traditionally, walruses were hunted using large harpoons similar to the harpoons used in bowhead whaling. Long lines, often made of walrus skin, were attached to the harpoons and fastened to a large piece of ice or were held by the hunter who used a smaller spear to drive the end of the line into the ice. Walruses were harpooned while they were lying on the ice. When the harpooned walrus dove, the line prevented it from escaping. When the walrus tired, it was killed with a lance through the heart. Occasionally, walruses were hunted from umiaqs when they were encountered away from the pack ice. In those circumstances, floats were attached to the line or the line was fastened to the umiaq. The walrus was killed with a lance once it tired. Nelson (1969) summarized an elder recounting one traditional method of hunting walruses in which two hunters harpooned two walruses facing opposite directions. The lines from the two harpoons were quickly tied together, and the walruses pulled against each other until they tired enough to be killed with lances through the neck. Now, large rifles are used instead of harpoons, but the methods used to approach the walruses are the same. When a walrus herd is sighted, the ice surrounding the herd is evaluated. There must be enough ice-free water to allow approach and to allow sufficient time for the killed walrus to be butchered before ice closes in.

Walruses are approached slowly with the outboard running. Generally, walruses are approached to within 10 feet before they are shot. All hunters shoot at the same time and continue the volley until enough have been taken or the herd escapes into the water. Walruses must be shot in the brain or the anterior portion of the spinal cord to ensure a kill. Walruses will not float once killed, so any dead or seriously wounded walruses that fall into the water are considered struck and lost. Fay et al. (1994) reported that up to 42% of walruses struck in Alaskan hunts lrom 1952 to 1972 were lost. Wounded walruses are often dangerous, and Nelson (1969) recounted several instances in which wounded walruses damaged boats. In feet, walruses can be so aggressive that they have disrupted mail delivery by kayak and even forced the abandonment of a settlement in Greenland.

Walrus flippers “ripened’ in seal oil are considered a delicacy in much of the Arctic. Select portions of meat are eaten, but the bulk of the walrus was used to feed the hunters” dog teams. The skin, bones, and especially the tusks were the most valuable parts of the walrus. Walrus skins often replaced bearded seal skins oil umiaqs in places where bearded seals were not abundant. Walrus skins were also used to create strong lines that were attached to harpoons used in seal, walrus, and whale hunting. The bones of walruses were used to make tools, and the ivoiy tusks were often used to make harpoon points and foreshafts. Now, ivory is used in artwork and much is sold to generate a cash income.

V. Polar Bears, nanuq

Polar bears are found throughout the Arctic and are hunted through much of their range. Polar bears remain oil the pack ice for most of the year, and most limiting takes place during the winter oil the pack ice. Polar bears are also taken opportunistically when they are encountered on land or in open water.

Polar bear hunting is considered one of the most dangerous hunting activities and successful hunters often enjov high status in village communities. Traditionally, single hunters using spears, lances, or knives hunted polar bears. Boas (1964) and Nelson (1969) both described polar bear hunts before the introduction of rifles. In the Canadian and Greenlandic Arctic, it was common to release dogs to chase the bears and tire tliein. Once the bears stopped, they were approached on foot and killed with lances or spears. Dogs were not used commonly in Alaska, but were released if the bears were on young, unsafe ice. Spears and lances were quickly given up once rifles became available.

Hunting for polar bears is now nearly always done oil the sea ice, and hunters often travel far offshore to find bears. Walking used to be the preferred method of transportation because it offered the advantages of a silent approach and the ability to hide quickly among the ice hummocks and ridges. Now, snowmobiles are preferred. With snowmobiles, hunters can pull sleds to transport the meat and hide back to the village, eliminating the need to drag the hide and then return with dogs to transport the meat.

Hunters usually find tracks rather than finding the animal itself. From the tracks hunters can tell the size of the animal, its direction and speed, and how long ago the bear passed. Tracks are followed until the bear is sighted. The hunter can then either move quickly to overtake the bear or move ahead to wait in ambush. In either case, it is important to get as close to the bear as possible to ensure a lethal shot. Wounded polar bears are dangerous and sometimes attack the hunter. If tile bear is in a position that the hunter cannot reach, the hunter will sometimes trv to lure the bear closer by mimicking a sleeping seal. Once the bear stalks close enough, the hunter picks up his rifle and shoots. Sometimes hunters leave seal blood or blubber on the ice and return to the area later to see if any bears have been lured by the smell. When bears venture close to villages or whaling camps they are almost always shot.

Polar bears are hunted for both their meat and their hides, which are divided among the village according to local tradition. In Greenland, the person who sights the bear becomes its “owner” regardless of whether they participate in the hunt. Any other people who shoot tile bear or touch it before it is killed also receive shares of the bear. In Alaska and Canada, shares were traditionally distributed widely within the village. A young hunter’s first bear was shared among all the people in the hunting party or was distributed to the elders in the village if he was hunting alone. Now, the shares are distributed less formally, but meat is usually shared with family members and others outside the family. The successful hunter usually keeps the hide.

Polar bear meat is prized by many people in the Arctic. Meat is always well cooked to prevent trichinosis, and the liver is never eaten due to high concentrations of vitamin A. In Alaska the sale of polar bear hides is prohibited by the Marine Mammals Protection Act of 1972. Hides are used for clothing such as boots, mittens, or trim for parkas and also for sleeping mats when camping oil the ice. In Greenland, polar bear skins were used for warm hunting pants, but now all skins are sold to Greenland’s trading department. Since 1994, polar bear hunters in Greenland have been able to sell bear meat to restaurants and hotels.

VI. Conclusion

Inuit and their ancestors have limited marine mammals for thousands of years. The technology and techniques of hunting marine mammals evolved in a culture intimately associated with the sea and the creatures that inhabit it. In modern times, the technology and techniques of hunting marine mammals have changed, but many traditions and beliefs remain. Marine mammal hunting provides access to status within the community and a sense of self-worth for a generation of Inuit struggling to cope with the burdens of cultural assimilation. It is the traditions and beliefs that are necessary for marine mammal hunting to remain an important part of the Inuit people’s subsistence and cultural lives.