The gastrointestinal tract consists of all structures derived 1 from the primitive gut tube and distal to the esophagus, including the stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and those accessory structures that have formed from that part of the gut (liver, gallbladder, pancreas, hepatopancreatic duct, anal tonsils). The posterior boundary is the lower part of the anal canal where the mucous membrane of the gut ends and the epidermis begins. This article follows the terminology of Chivers and Langer (1994).

The anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract has long fascinated workers. Grew (1681) is the earliest worker who dealt with that topic exclusively. Tyson (1680), in his marvelous treatment of the anatomy of the harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena), went extensively into the gastrointestinal tract. Owen dissected the dugong (Dugong dugon) (1838) and then summarized all the information on the digestive system of mammals in his magnum opus on comparative anatomy (1868). William Turner did extensive studies of the stomach of cetaceans, which are summarized in his catalog of the specimens of marine mammals in the Anatomical Museum of the University of Edinburgh (1912). Langer (1988) and Reynolds and Rommel (1996) did a very good treatment of the gastrointestinal tract of the sirenians.

Measurements of the gastrointestinal tract, both in terms of length and volume, are extremely difficult due to the elasticity of the organs. At death the muscles lose their tonus and the length and volume can double or triple (Slijper, 1962).

The parts of the gastrointestinal tract are described starting with the stomach and progressing distally. The anatomy of each part is treated in sequence according to the following classification: Pinnipedia (Phocidae, Otariidae, Odobenidae); Sirenia (Dugongidae, Trichechidae); Cetacea-Odontoceti [Delphinoidea (including Phocoenidae and Monodontidae), Platanistoidea (including Platanistidae, Iniidae, Pontoporiidae, and Lipotidae), Physeteroidea, Ziphiidae]; and Mysticeti (Balaenopteridae, Bal-aenidae, Eschrichtiidae, Neobalaenidae). The major features of the gastrointestinal tract are summarized in Table I.

I. Major Organs

A. Stomach

The stomach is a series of compartments starting with the cardiac, fundic, and ending with the pyloric. The boundary of the stomach with the esophagus is determined by the epithelial type: stratified squamous for the esophagus and columnar for the stomach. The distal boundary is marked by the pyloric sphincter.

The stomach is suspended by the mesogastrium, which, in development, becomes complexly folded and differentiated into the greater and lesser omenta.

1. Pinnipedia The stomach in pinnipeds is relatively uncomplicated when compared to the rest of marine mammals. The stomach in the California sea lion (Zalophus californianus) consists of a simple cardiac chamber into which the esophagus enters, followed by a narrowing into the pyloric chamber. There is a prominent pyloric sphincter. The pyloric end of the stomach is strongly recurved onto the cardiac portion. The stomach in the southern sea lion (Otaria flavescens) and Weddell seal (Leptomjchotes weddellii) does not differ from the California sea lion. The stomach of the walrus (Odobenus rosmarus), although it is not described in any detail, does not appear to differ markedly from that of the other pinnipeds.

Pinnipeds seem to follow the carnivore plan of a relatively simple single-chambered (monolocular), nonspecialized stomach.

2. Sirenia The stomach in the dugong is moderately complex. Externally it is a simple oval organ with the esophageal opening in the center. Internally, there is a ridge (gastric ridge) that divides the stomach into two compartments: the cardiac and pyloric portions. There is development of a powerful sphincter up to 4 cm thick at the esophageal/gastric junction (Owen, 1868). The stomach walls are highly muscular. The cardiac gland is roughly spherical and about 15 cm in diameter in adults. The cardiac gland opens into the first compartment, where the esophagus also opens. The mucosa in the cardiac gland is packed with gastric glands that are distinguishable from the glands in the main stomach compartment. The glands consist of chief and parietal cells at a ratio of 10:1. The mucosa in the cardiac glands is arranged in a complex plicate structure. The pyloric aperture is in the second compartment. The cardiac region of the stomach extends for several centimeters from the esophageal junction. The stomach is lined by gastric glandular epithelium with a particular abundance of goblet cells and mucus-secreting gastric glands.

TABLE I

Comparative Morphology of the Gastrointestinal System of Marine Mammals

|

|

|

|

Stomach |

|

|

|

|

Small intestine |

|

|

Large |

intestine |

|

Accessorij organs Hepato- |

|

|||

|

|

|

|

Main |

Connecting |

Pyloric |

Cardiac |

|

Duodenal |

Duodenal |

|

|

|

|

|

Gall- |

Pan |

pancreatic |

Anal |

|

Toxon |

Type |

Forestomach |

stomach” |

chambers |

stomach |

gland |

Duoenum |

ampulla |

diverticula |

Jejunum1‘ |

Ileum |

Cecum |

Colon |

Liver |

bladder |

creas |

duct |

tonsils |

|

Pinnipedia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Phocid |

Unilocular |

Absent |

Present |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

Present |

Absent |

Absent |

Undiff. |

Undiff. |

Present |

Present |

Multilobed |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

Absent? |

|

Otariid |

Unilocular |

Absent |

Present |

Absent |

Absent |

Absent |

Present |

Absent |

Absent |

Undiff. |

‘ Undiff. |

Present |

Present |

Multilobed |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Absent? |

|

Odobenid |

Unilocular? |

Absent? |

Present? |

Absent? |

Absent |

Absent? |

Present |

Absent |

Absent? |

Undiff. |

Undiff. |

Present |

Present |

Multilobed |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Absent? |

|

Sirenia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dugon id |

Unilocular |

Absent |

Present |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Undiff. |

Undiff. |

Hvper. |

Present |

Multilobed |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

Absent? |

|

Trichechid |

Unilocular |

Absent |

Present |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Undiff. |

Undiff. |

H\per. |

Present |

Multilobed |

Present? |

Present |

Absent |

Absent? |

|

Cetacea |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mysticete |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Balaenopterid |

Plurilocular |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

Undiff. |

Undiff. |

Present |

Present |

Bilobed |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Absent? |

|

Eschrichtiid |

Plurilocular |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

? |

? |

Absent |

? |

? |

Present? |

Present? |

Bilobed |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Present |

|

Balaenid |

Plurilocular |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

? |

■? |

Absent |

? |

? |

Absent |

Undiff. |

Bilobed |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Absent? |

|

Neobalaenid |

Plurilocular |

Present |

Present |

? |

Present |

Absent |

? |

|

Absent |

? |

? |

Present? |

Present? |

Bilobed |

Absent |

Present |

Present? |

Absent? |

|

Odontocete |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Delphinoid |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Delphinid |

Plurilocular |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

Undiff. |

Undiff. |

Absent |

Undiff |

Bilobed |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

|

Phocoenid |

Plurilocular |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

Undiff. |

Undiff. |

Absent |

Undiff. |

Bilobed |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Absent? |

|

Monodontid |

Plurilocular |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

Undiff. |

Undiff. |

Absent |

Undiff. |

Bilobed |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Absent? |

|

Platanistoid |

Plurilocular |

Variable |

Hyper. |

Variable |

Variable |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

Undiff. |

Undiff. |

Variable |

Undiff. |

Bilobed |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Variable |

|

Physeteroid |

Plurilocular |

Present |

Present |

Present? |

Present |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

Undiff. |

Undiff. |

Absent |

Undiff. |

Bilobed |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Present? |

|

Ziphiid |

Plurilocular |

Absent |

Variable |

Hvper. |

Present |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Absent |

Undiff. |

Undiff. |

Absent |

Undiff. |

Bilobed |

Absent |

Present |

Present |

Absent? |

|

“hypertropbied. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

”undifferentiated. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The stomach of the dugong appears to be modified to secrete mucus to aid in lubricating the ingested material and prevent mechanical abrasion to the mucosa. It is interesting that the salt content of the dugong diet is high; sodium is about 30 times and the chloride about 15 times that of terrestrial pasture plants.

The stomach in the recently extinct Hydrodamalis gigas (Steller sea cow) was apparently very large. According to Steller, it was 6 feet long and 5 feet wide when distended with masticated seaweed.

The stomach in the manatees (Trichechus spp.) is very similar to that in the dugong. The stomach is divided by a muscular ridge into cardiac and pyloric regions. A single cardiac gland opens into the cardiac region of the stomach.

3. Cetacea The cetacean stomach is a diverticulated composite stomach (pleurolocular), consisting of regions of stratified squamous epithelium, fundic mucosa, and pyloric mucosa.

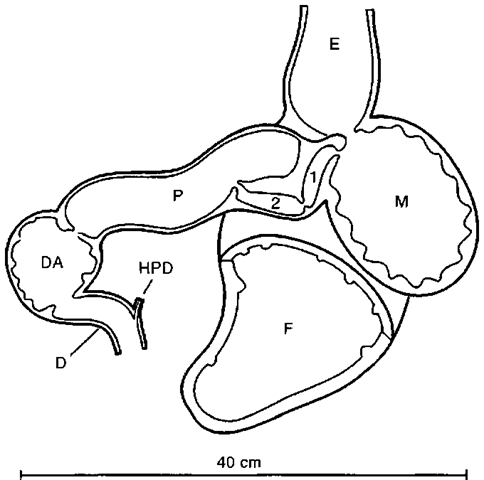

The stomach, as typified by a delphinid, consists of four chambers (Fig. 1). These have been referred to by a variety of anatomical terms: forestomach (first, esophageal compartment, paunch), main stomach (second, cardiac, fundus glandular, proximal), connecting chamber (third, fourth, “narrow tunneled passage,” “conduit etroit,” intermediate, connecting channel, connecting division), and pyloric stomach (third, fourth, fifth, pyloric glandular, distal).

a. forestomach

There has been discussion about the homologies of the forestomach in Cetacea. It is fined with stratified squamous epithelium, like the esophagus, and there was reason to believe that it was just an esophageal sacculation. Embryological work in the common minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) demonstrated that the forestomach was formed from the stomach not the esophagus and that it was homologous to the forestomach of ruminants.

Odontocetes

Delphinoid: The forestomach is lined with stratified squamous nonkeratinized epithelium. The epithelial lining is white in freshly dead animals and is thrown into a series of longitudinal folds when empty. The forestomach was often referred to as the “paunch” in older literature. Like the other chambers in the stomach, it is variable in size. It is pyriform and on the order of 30 cm long in an adult Tursiops truncatus (280 cm total length). The forestomach is highly muscular but has no glandular functions. The forestomach/main stomach is a wide opening (3 to 5 cm in adult Tursiops) in the wall of the forestomach near the esophageal end. The forestomach functions as a holding cavity analogous to the crop of birds or the forestomach of ungulates. Because the communication with the main stomach is so wide, there is a reflux of digestive fluids from the main stomach and some digestion takes place in the forestomach.

Figure 1 Stomach of a spinner dolphin, Stenella longirostris, ventral view. D, duodenum; DA, duodenal ampula; E, esophagus; F, forestomach; HPD, hepatopancreatic duct; M, main stomach; P, pyloric stomach; 1, 2, compartments of connecting chambers.

The same general relationships hold in Phocoena, Delphi-napterus leucas, and Monodon monoceros. Platanistoid: The forestomach is unusual in Inia geoffrensis and Platanista gangetica in that the esophagus runs directly into the main stomach and the forestomach branches off the esophagus. In the two other families of platanistoids, the forestomach is lacking entirely.

Physeteroid: The forestomach is present in Physeter macrocephalus. It was a compartment about 140 and 140 cm, lined with yellowish-white epithelium in a 15.6-m male.

Ziphiidae: The forestomach is absent in all ziphiids.

Mysticetes

The forestomach is present in all species of mysticetes.

b. main stomach The main stomach has a highly vascular, glandular epithelium that is grossly trabeculate. The epithelium of the main stomach is dark pink to purple. The main stomach secretes most of the digestive enzymes and acids and where digestion commences. It has also been known as the fundic stomach. It is present in all cetaceans.

Odontocetes

Delphinoid: The main stomach is approximately spherical and on the order of 10-15 cm in adult Tursiops. The same general relationships hold in Phocoena, Delphinapterus, and Monodon.

Platanistoid: In Platanista there is a constricting septum of the main stomach that forms a small distal chamber, through which the digesta must pass.

Lipotes vexillifer presents an unusual situation in having three serially arranged main stomach compartments. The second and third compartments are very much smaller than the first and are topographically homologous with the connecting chambers. However, they are lined bv epithelium that has fundic glands, typical of the main stomach.

Physeteroid: There is nothing remarkable about the main stomach of physeteroids.

Ziphiid: Some ziphiids develop a subdivision in their main stomach. There is an incipient constriction in the main stomach of Berardius bairdii and Mesoplodon bidcns that divides the stomach into two compartments. The connecting chambers exit off the second compartment. Another type of stomach modification has occurred in Mesoplodon europaeus and M. minis, where a large septum has developed, forming a blind diverticulum in the main stomach. An additional septum has developed in the diverticulum in Mesoplodon europaeus subdividing it.

Mysticetes

There is nothing remarkable about the main stomach in mysticetes.

c. connecting chambers The connecting chambers, also called the connecting channel, the intermediate stomach, and the third stomach are present in all Cetacea. They are lined with pyloric epithelium and are easily overlooked in dissections. They are small in most cetaceans but have been developed greatly in ziphiids. Because of their proliferation in ziphiids, where they seem to function as something more than channels between the main and pyloric stomachs, their name was changed from connecting channels to connecting chambers.

Odontocetes

Delphinoid: The connecting chambers in a typical delphi-noid consist of two narrow compartments lying between the main stomach and the pyloric stomach. The diameter of the connecting chambers is 0.8 cm in adult Tursiops and the combined length is 7-9 cm. The epithelial lining is very similar to pyloric stomachs. In some species the compartments are simple serially arranged; in others they may have diverticulae.

The same general relationships hold in Phocoena, Delphinapterus, and Monodon.

Platanistoid: They occur in all the species of platanistoids, with the exception of Lipotes. In that species the compartments lying between the main stomach and the pyloric stomach (second and third compartments of the main stomach) are lined with epithelium containing fundic and mucous glands in the first compartment and fundic glands in the second compartment. This would make them subdivisions of the main stomach. The connecting chambers appear to be absent in Lipotes.

Physeteroid: Although none of the works that describe the sperm whale stomach mention the connecting chambers, there is no reason to assume that they are absent.

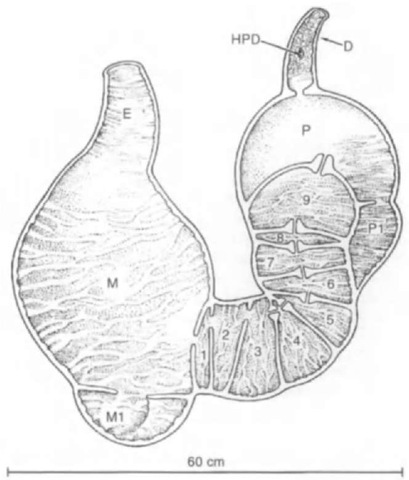

Ziphiid: The connecting chambers in ziphiids are globular compartments, ranging in number from 2 to 11 (Fig. 2). They are separated by septa and communicate by openings in the septa. The openings are either central or peripheral in the septa. The connecting chambers are lined with pyloric epithelium. The connecting chambers in specimens of adult Mesoplodon (ca. 5 m long) are about 10 cm in diameter.

Figure 2 Stomach of a Gulf Stream beaked whale, Mesoplodon europaeus, dorsal view. D, duodenum; DA, duodenal ampulla; E, esophagus; HPD, hepatopancreatic duct; M, main stomach: Ml, accessory main stomach; P, pyloric stomach; PI, accessory pyloric stomach; 1, 2, etc., compartments of connecting chambers.

Mysticetes

Balaenopterid: Many workers have described the connecting chambers in a number of species of Balaenoptera (blue, B. musculus: fin. B. physalus; sei, B. borealis: minke, B. acu-torostrata and B. bonaerensis). The connecting chambers in common minke whales are 10 to 30 cm in length.

Balaenid: The inflated connecting chambers in an 8.5-m female Balaena mysticetus were 5 cm in diameter and 17 cm combined length. The presence of connecting chambers was not mentioned in dissections of right whales.

Eschrichtiid: The connecting chambers are relatively large in a newborn Eschrichtius robustus.

Neobalaenid: There are no data on the connecting chambers in C-aperea marginata.

d. pyloric stomach

Odontocetes

Delphinoid: The pyloric stomach in delphinoids is a simple tubular cavity lined bv typical mucous-producing pyloric glands. The epithelium is in many ways similar to the epithelium of the small intestine. The pyloric stomach is about 20 cm long and 4 cm in flat diameter in an adult Tursiops.

The same general relationships hold in Phocoena, Delphi-naptenis, and Monodon.

Platanistoid: The pyloric stomach in Platanista gangetica is a single chamber about 12 cm long and contains abundant large tubular pyloric glands. The pyloric stomach is comparable in lnia and Pontoporia, but differs markedly in Lipotes. In that species it is differentiated into a proximal bulbous compartment and a smaller distal compartment. The epithelial lining in Lipotes is similar to all other Cetacea.

Physeteroid: Available data on the pyloric stomach of phy-seterids are scanty. The pyloric compartment is present and there is no reason to assume that it is different from the rest of the cetaceans.

Ziphiid: The pyloric stomach in a newborn Ziphius is a simple spherical compartment that measures about 10 cm in diameter. It is lined with smooth pyloric epithelium and communicates with the duodenum through a strong pyloric sphincter. This is also the case in Hyperoodon spp., Tasmacetus, and some species of Mesoplodon (M. densirostris, M. hectori, and M. ste-jnegeri).

In Berardius bairdii the main pyloric compartment has expended in volume to where it is nearly the size of the main stomach and has developed a small distal accessory chamber. The pyloric compartments are in series, with the accessory chamber communicating with the duodenum.

In all other species of Mesoplodon examined to date (M. bidens, M. europaeus, and M. mints), a blind diverticulum has developed. The diverticulum comes off the proximal side of the pyloric stomach and lies along the distal connecting chambers. The accessory pyloric stomach communicates with the pyloric stomach through a wide opening.

Mysticetes

Balaenopterid: In all of the balaenopterid species examined (B. acutorostrata, B. borealis, B. musculus, and B. physalus), the pyloric stomach is smaller than the stomach. The pyloric stomach contains 8.5 to 12.1% of the total inflated stomach volume (18-391).

Balaenid: The balaenids appear to be similar to the balaenopterids.

Eschrichtiid; In a dissection of a newborn Eschrichtius, the pyloric compartment seemed to be comparable to that in balaenopterids.

Neobalaenid: There are no data available on the pyloric stomach in Caperea.

B. Small Intestine

The small intestine starts at the pyloric sphincter. Digestion continues in the small intestine where absorption of the nutrients takes place. The duodenum derives its names from its length of about 12 inches (30 cm) in humans. It has no mesentery and its wall has longitudinal folds. The hepatic and pancreatic ducts open into the duodenum.

The longitudinal folds of the duodenum become circular (plicae circulares) in the jejunum. The jejunum starts when the small intestine becomes suspended by a mesentery.

Differentiation between the jejunum and the ileum is not sharp. The distal portions of the ileum contain longitudinal folds, which differentiates it from the proximal portion of the jejunum, which contains circular folds. The distal boundary of the ileum is sharp. The diameter of the intestine increases at the ileocolic orifice. This orifice is usually provided with a sphincter permitting partial closure.

The small intestine is characterized by the presence of absorptive villi in the mucosa.

1. Pinnipedia

Phocid: The demarcation between pylorus and duodenum is not sharply marked by position of the duodenal (Bnmner’s) glands in Leptonychotes weddelli. The duodenum is 1 or 2 feet in lengdi. Small plicae circulares and short irregular villi were present in the duodenum. Jejunum and ileum are hard to differentiate.

Phoca vitulina has a small intestine of “great length “: 40 feet (~12 m) in a seal 3 feet (91 cm) long (snout —> end of flippers). An adult male Mirounga leonina (4.80 m si) had a small intestine length of 202 m.

Otariid: Otaria flavescens lacks plicae circulares, with villi being arranged on delicate transverse linear folds. Eumetopias jubatus has a small intestine length of 264 feet (~80 m).

Odobenid: Owen (1853) described the intestine in passing in his description of a young walrus. The small intestine was 75 feet (~23 m) long, the cecum was 1.5 inches (3.8 cm), and the large intestine was 1 foot (~30 cm) in length.

2. Sirenia The duodenum of the dugong and manatees has two duodenal diverticula that are crescentic in shape and about 10-15 cm long, measured in the curve. They communicate via a common connecting channel with the duodenum. The lining of the diverticulae is similar to the pyloric region of the stomach and contains mucous glands. The duodenum is about 30 cm in length, similar to other medium-sized mammals. Both the duodenum and the diverticulae contain prominent plicae circulares. There is a weak sphincter at die distal end of the duodenal ampulla. The length of the small intestine is from 5.4 to 15.5 m, four to seven times the body length of the animal. The small intestines were about 1 inch (2.5 cm) in diameter in the juvenile that Owen dissected. Brunner’s glands are present in the duodenum and diverticulae. Paneth cells are absent in contrast to most domestic terrestrial herbivores. The diverticulae appear to enlarge die surface of the proximal duodenum, which would allow a larger volume of digesta to pass from the stomach at one time.

3. Cetacea Odontocetes

Delphinoid: In delphinoids there is no cecum and no marked differentiation between large and small intestines. Intestine length ranged between 8.85 and 16.80 m in specimens of Tursiops, Delphinus delphis, and Stenella spp. (total lengths from 160 to 230 cm). There is a duodenum about 30 cm long, but differentiation between a jejunum and ileum is lacking. Examination of the small intestines by light microscopy revealed a lack of well-developed villi in delphinids.

Platanistoid: The length of the small intestine in a 204-cm lnia geoffrensis was 4.15 m. The duodenum was approximately 20 cm long. The jejunum was not differentiated from the ileum. A prominent longitudinal fold began at the opening of the lie-patopancreatic duct in the duodenum and continued throughout the small intestine. The small intestine varied in diameter from 0.7 to 0.8 cm. The small intestine graded into a “smooth-walled portion” that was 1 cm in diameter. The authors were unable to tell where the small intestine ended and the large intestine began. The “smooth-walled portion” was 80 cm in length and graded into the colon distally.

There are no plicae circulares or typical villi in the intestine of Pontoporia. A distinct uninterrupted longitudinal fold occurs in the small intestine.

There were abundant plicae circulares in the proximal part of the intestine in Platanista gangetica, changing to longitudinal folds in the last meter or two. There was a prominent cecum and an ileocolic sphincter.

The small intestine in most platanistids is extremely long. The ratio of small to large intestine length is between 50 and 60% in Pontoporin, 50% in Inia, but only around 9% in Platanista.

Physeteroid: The total intestinal length in adult sperm whales can range up to 250 m. The plicae circulares were unusual in that they appeared to be spiral, giving the impression of a spiral valve in sharks. There is no cecum and the transition between the small and the large intestine is gradual.

Ziphiid: It is said that the combined intestinal length of Hy-peroodon is six times the body length. There is a unique vascular rete (mirabile) intestinale associated with the large and small intestine in at least Ziphins cavirostris and Berardius spp. There is no cecum.

Mysticetes

Balaenopterid: The mean ratio of the length of the small intestine to body length in minke whales (Balaenoptera acu-torostrata) was rather small (3.92) and averaged 36 m in length. The minke whale possessed a duodenal ampulla, but there was no indication of differentiation of the jejunum and ileum.

Balaenid, Eschrichtiid, and Neobalaenid: Nothing is available on the anatomy of the small intestine for balaenids, eschrichtiids, and neobalaenids.

C. Large Intestine

The large intestine consists of the colon (ascending, transverse and descending), cecum, rectum, anal canal, and anus. The cecum is a diverticulum off the proximal end of the colon, near the ileocolic juncture. The sigmoid colon of humans is that portion of the distal end of the colon that has its mesocolon extended so that it is free in the brim of the pelvis.

The colon is suspended by a mesentery (mesocolon). The colon functions to absorb water and consolidate fecal material. Most mammalian colons have their longitudinal muscle fibers arranged into bands called taenia coli. The colon is formed into sacculations, which are called haustra. The rectum is the straight portion of the large intestine that transverses the pelvis. The anal canal is the specialized terminal portion of the large intestine. The anal canal has many lymph nodes and glands that reflect the difficulties of fecal excretion. The anus represents the end of the gastrointestinal tract. The anal sphincter controls excretion of fecal wastes.

1. Pinnipedia In pinnipeds the cecum is short and blunt or round is not present. The large intestine is relatively short and not much larger in diameter than the small intestine. No taenia coli, plicae semilunares. haustra, and appendices epiploicae are present.

Phocid: The colon is about 6 feet (183 cm) long in an adult Leptonychotes. The colon grades into the rectum, which begins at the pelvic inlet and ends at the anal canal. Throughout the length of the rectum the lining is thrown into large irregular transverse rectal plicae. Toward the distal portion of the rectum, the plicae become organized into five longitudinal anal columns that continue into the anal canal. The anal canal is much smaller in diameter than the rectum. Small coiled tubular rectal glands were present. The anal canal ends where the mucosa changes into a pigmented cornified stratified squamous epithelium (epidermis). Circumanal glands, coiled tubular structures, representing modified sweat glands, were confined exclusively to this region. In Leptonychotes there was no evidence of other anal glands, sacs, or scent glands.

2. Sirenia The cecum in the dugong is conical and was about 6 inches (—-15 cm) long and 4 inches (—-10 cm)wide at the base in the half-grown specimen. A sphincter is present in the ileocecal juncture. There is no constriction between the cecum and the colon. The epithelial lining of the cecum is smooth and its walls are muscular.

The colon in the dugong is thinner walled than the small intestine and is between 4 and 11 times the total body length. There are no taeniae coli. The lining of the colon is smooth, with the exception of irregular folds that are present at the wider terminal portion. The lining of the rectum is provided with longitudinal folds, which become finer and more numerous in the anal canal. The lining of the anus is graver and harder than the lining in the rectum. The anal canal is about 5 cm long. At the distal end of the canal the longitudinal folds become higher and terminate in globular swelling, which occlude the lumen and which have been termed “anal valves.”

The cecum in manatees is very pronounced and unusual in shape. It is an oval body about 20 cm in diameter and has two horn-shaped appendages that can reach up to 15-20 cm in length.

3. Cetacea Odontocetes

Delphinoid: As was stated earlier, there is no cecum and no marked differentiation between large and small intestines in delphinoids.

Platanistoid: The colon in a 204-cm Inia geojfrensis was 40 cm long, followed by a 5-cm rectum and a 3-cm anal canal. The proximal and distal portions of the colon were 1 and 1.5 cm in diameter, respectively.

There is a pronounced cecum that is 5 to 9 cm long in Platanista gangetica. The large intestine is short, 60 cm in adults. Lengths of the large intestine (cecum, colon, rectum, and anus) in four specimens that ranged between 76 and 127 cm total length ranged from 25.5 to over 58 cm (the 127-cm specimen was lacking the cecum). There was no trace of taenia coli.

There is no cecum in Pontoporia. The longitudinal fold in the small intestine of Pontoporia becomes two distinct longitudinal folds. Taenia and haustra coli were not found.

Physeteroid: In large adult Physcter the large intestine can be up to 26 m long. The mucosa of the large intestine in Phy-seter is not folded. There is no cecum. The diameter of the descending colon is increased markedly in Kogia spp.

Ziphiid: There is no cecum and the transition between large and small intestines is gradual.

Mysticetes

Mysticetes have a very short cecum except in the case of right whales where the cecum is absent. There is a marked difference between the diameter of the large and small intestines in right whales (Eubalaena spp.). There is one mention of taeniae and haustrae coli in the blue whale where the taeniae consisted of three longitudinal muscular bands.

Balaenopterid: The mean ratio of the large intestine to body length in common minke whales was 40%. The mean ratio of cecum length to body length was 4%; the cecum varied between 30 and 50 cm.

Balaenid, Eschrichtiid, and Neobalaenid: There appears to be no specific data for the large intestine of balaenids, eschrichtiids, and neobalaenids.

II. Accessory Organs

A. Liver

The liver is derived from a diverticulum of the embryonic duodenum. That diverticulum also gives rise to the gallbladder, which serves as a reservoir for hepatic secretions. The liver expands to become the largest internal organ. The liver functions in the storage and filtration of blood, in the secretion of bile, which aids in the digestion of fats, and is concerned with the majority of the metabolic systems of the body.

1. Pinnipedia The fiver is multilobed in pinnipeds: up to seven or eight lobes have been reported in Otaria.

2. Sirenia The diaphragm has become oriented in the dorsal plane instead of the transverse plane, as it is in other mammals. The liver in the dugong and manatees is flattened against the dorsally oriented diaphragm. The liver is composed of four lobes: the normal central, left and right and the fourth. Spigelian lobe that lies on the dorsal border of the liver and is closely associated with the vena cava.

3. Cetacea The liver in cetaceans is divided into two lobes by a shallow indentation. Occasionally a third intermediate lobe develops. Because relative liver weights are more than would be expected, the tentative conclusion is that cetaceans, particularly odontocetes, may have increased metabolic rates.

B. Gallbladder

The gallbladder is located on the posterior side of the liver where the hepatic duct issues. The developmental origins of the pancreas, liver, and gallbladder are related. The gallbladder stores and concentrates the bile that is secreted bv the liver.

1. Pinnipedia The gallbladder is present universally in pinnipeds and tends to be pyriform and located in a fossa of one of the subdivisions of the right lobe of the liver.

2. Sirenia The gallbladder is small in the dugong and is strongly sigmoid in shape. It lies on the ventral surface of the central lobe where the falciform and round ligaments attach. It does not appear to be described in manatees.

3. Cetacea The gallbladder is absent in all members of the order Cetacea. Part of this lack is compensated for by an increased capacity for storage in the hepatic and bile duct system.

C. Pancreas

The pancreas develops out of outgrowths of the embryonic duodenum. It consists of two developmental bodies, the dorsal and ventral pancreas, which may empty into either the hepatic duct or directly into the duodenum. The pancreas secretes enzymes that are discharged into the duodenum and insulin that is discharged directly into the blood.

The pancreas in marine mammals appears to have no remarkable differences from that in other mammals.

D. Hepatopancreatic Duct

The hepatopancreatic duct represents the developmental fusion of the hepatic, ventral, and dorsal pancreatic ducts. The hepatopancreatic duct opens into the duodenum through the major duodenal papilla.

1. Pinnipedia

Phocids: In Phoca vitulina and Leptonychotes the pancreatic duct joined the common bile duct before either of them come into contact with the duodenum. In this case they coalesce to form a hepatopancreatic duct, which empties into the duodenum.

Otariids and Odobenids: In Otaria and Odobenus the pancreatic duct and common bile duct empty separately into the duodenum. In the case of Odobenus the two ducts coalesce within the walls of the duodenum and enter via a common opening.

2. Sirenia A hepatopancreatic duct does not form in the Sirenia: the common bile and pancreatic ducts open separately into the duodenum.

3. Cetacea The bile duct and pancreatic ducts coalesce into a hepatopancreatic duct in all known cetaceans.

E. Anal Tonsils

Tonsils are bodies of organized lymphatic tissues around crypts used to communicate to the lumen of whatever system they are in. They are most common in the digestive system where everyone is familiar with the tonsils at the back of the throat. In some marine mammals, clusters of lymphatic tissue that fall into the definition of tonsils occur at the other end of the digestive system, in the anal canal.

1. Pinnipedia and Sirenia There is no mention of anal tonsils in pinnipeds or sirenians. There is enough description of the anal canal to be relatively certain that they do not occur.

2. Cetaceans Odontocetes

Delphinoid: Anal tonsils have not been reported in delphi-noids.

Platanistoid: Anal tonsils were found in the anal canal of Platanista gangctica and Stenella coendeoalba. Lymphoid tissue was found in the anal canal of lnia geoffren.sis that was not organized into structures that could be called tonsils. There was no trace of lymphatic tissue in the anal canal of Pontoporia blainvillei.

Physeteroid: Similar structures were also found in some sperm whales in South Africa. These were noticed upon external examination of the whales, so they were at the distal end of the anal canal. There were no comparable data on other whales so their findings may have represented abnormal swelling in normal lymphatic tissue.

Ziphiid: No anal tonsils have been reported in ziphiids.

Mysticetes

Eschrichtiid: Anal tonsils were found in the gray whale. These tonsils consisted of masses of lymphatic tissue that communicated with the anal canal via crypts. They lie near the boundary of the anal canal with the rectum, 30 to 40 cm from the anal orifice.

Balaenopterid, Balaenid, and Neobalaenid: No anal tonsils have been reported.