I. Diagnostic Characters

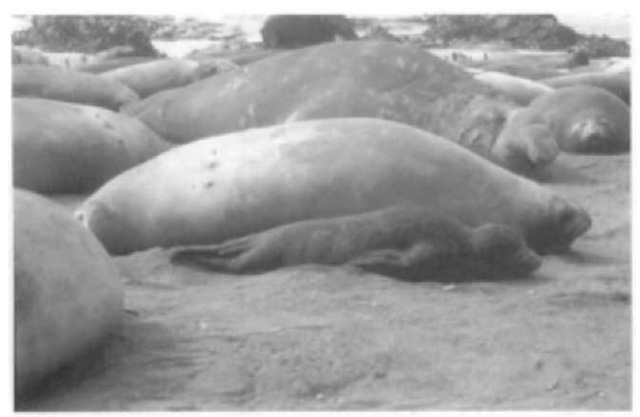

The northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris) and the southern elephant seal (Mirounga leonina) are the largest pinnipeds. The most striking characteristic of both species is the pronounced sexual dimorphism, with males weighing 8-10 times more than females. Male southern elephant seals have been recorded to weigh 3700 kg, whereas females only weigh between 400 and 800 kg. This makes the elephant seal the most sexually dimorphic of any mammal (Fig. 1). There are other pronounced secondary sexual differences in morphology, all of which are related to the highly polygynous mating strategy of the species. Most notable of these is the large proboscis of the male that plays a key part in dominance displays with other males.

The evolutionary origins of the species are unclear, with estimates of the divergence from a common ancestor ranging from as little as 10,000 years ago to as far back as the Pleistocene. Morphological differences between the species are, however, quite distinct and they are readily differentiated. The southern species is larger, with northern elephant seals rarely reaching more than 2300 kg. In both species, adult females exhibit a considerable range in body weight and there are no clear differences between them in this feature. Adult males of the northern species have a longer proboscis than the southern species. Northern elephant seals also have a more developed chest shield, a region of the neck, chest, and shoulders of thickened and scared skin associated with fighting. In the northern species, this has a distinctive red coloration. Females lack the proboscis and chest shields, but northern females are distinguished by a noticeably narrower and flatter nose than in the southern species.

Figure 1 Adult male (background), adult female, and newborn pup southern elephant seals. Adidt males weigh 8-10 times as much as the females, making them the most sexually dimorphic of all mammals.

II. Distribution

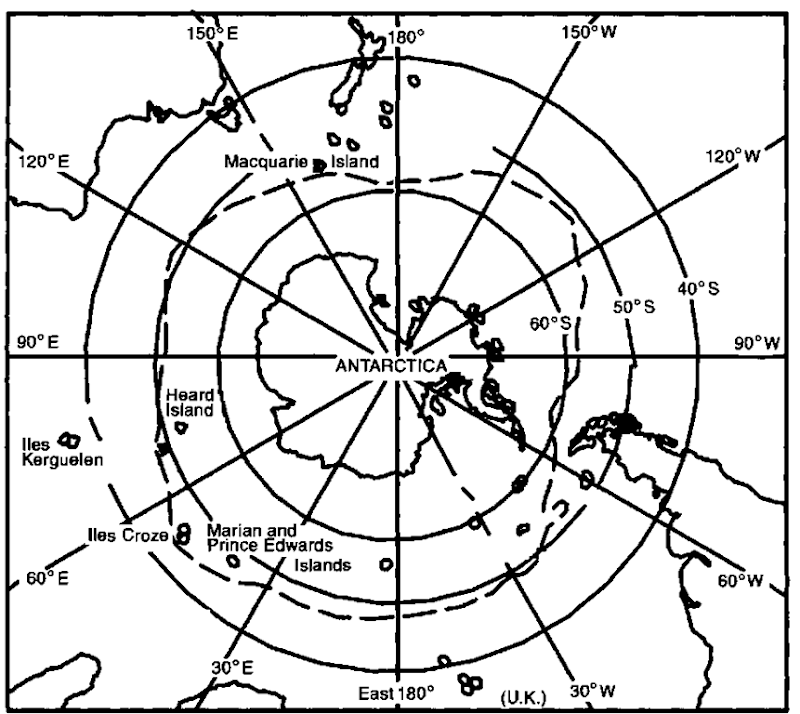

Despite their physical similarities, the two species have very different geographic distributions, with at least 8000 km separating them. Southern elephant seals have a more extensive range, with breeding sites on islands scattered right around the sub-Antarctic (Fig. 2). Very occasionally, pups are even born on the Antarctic mainland. Studies have indicated that when not ashore during the breeding season or for their annual molt, southern elephant seals utilize most of the Southern Ocean ranging from waters north of the Antarctic Polar Front (sometimes called the Antarctic Convergence) to the high Antarctic pack ice. There is some separation of feeding areas between the sexes, with males tending to feed in the more southerly waters associated with the Antarctic continental shelf.

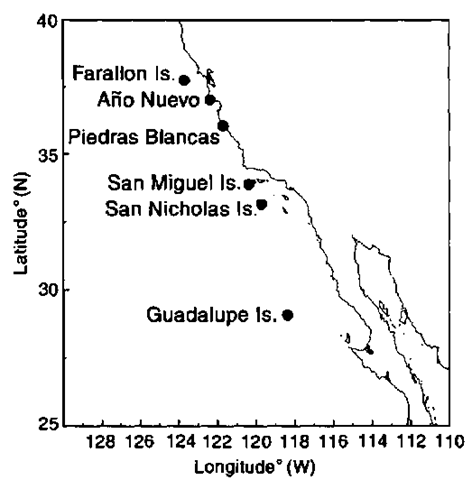

Northern elephant seals have a limited breeding distribution, pupping at approximately 15 colonies between Point Raines in northern California to the Baja California Peninsula in Mexico (Fig. 3). Most of the colonies occur on offshore islands, but a small number occur on the mainland coast. As with southern elephant seals, the northern species disperses widelv during the nonbreeding phase of its annual cycle. Many individuals travel northward along the North American coast to feed in the Gulf of Alaska and the Aleutian Islands, which is a round trip of more than 10,000 km. This migration is even more remarkable as many individuals make it twice per year, returning to their southern breeding grounds to molt. The northern species also exhibits sexual differences in foraging areas, with males tending to use the more northerly areas and females heading in a more northwesterly direction and feeding in deep oceanic waters of the North Pacific Ocean.

III. Human Interactions

Today, both species of elephant seal are relatively free of adverse interactions with humans. Southern elephant seals are only rarely captured in the nets of Southern Ocean fishing fleets, and this has never been reported for the northern species. There are some grounds for concern that some large-scale fisheries may be competing with the seals for preferred prey species, but this is difficult to quantify given the current paucity of information on the diet of both species.

However, both species have a long history of direct exploitation by humans as tliev were hunted extensively during the 1800s for their blubber, which yielded an unusually high-quality oil. In the case of the northern elephant seal, this hunting was so intense that the populations were reduced to a small group breeding on a single island by 1890. The more widespread and southerly distribution of the southern species meant that the exploitation was less intensive. Nonetheless, the seals were reduced dramatically at all of their major breeding sites. The exploitation of southern elephant seals also continued longer than that of northern elephant seals, with commercial operations continuing until 1919 at Macquarie Island and until 1964 at South Georgia.

IV. Geographic Variation

As a direct consequence of the extensive hunting in the 19th century, northern elephant seals passed through an intense genetic bottleneck, which has seen almost all genetic variation removed from the population. The relatively recent expansion onto several islands has not yet resulted in discernible genetic variation between the breeding groups.

In contrast, southern elephant seals have quite a clear genetic structure, with four distinct stocks: the southern Pacific Ocean, the south Atlantic, the southern Indian Ocean, and a small, but increasing population of Peninsula Valdes in Argentina. The integrity of the subpopulations appears to be maintained by the extremely low interchange rates between populations. Although genetically distinct, animals from the subpopulations are indistinguishable from each other in external features.

V. Population Size and Trends

Northern elephant seals are presently undergoing a rapid population increase and range extension, whereas the southern species is currently experiencing a decline in two of its three major populations.

Population declines in the order of 50% have been recorded in both the southern Indian and the southern Pacific Ocean populations since the 1950s and 1960s, whereas the populations in the South Atlantic are stable, or increasing. The current estimated total population size for southern elephant seals is 640,000. The underlying cause of the declines are presently unclear, but are thought to be related to changes in the distribution and abundance of the seal s prey.

Conversely, northern elephant seal populations are currently increasing at a rate of approximately 6% per annum. This is the latest phase in one of the most remarkable population recoveries of any mammal. The total number of northern elephant seals in 1890 is thought to have been less than 100 individuals after 50 years of intensive and indiscriminate hunting bv sealers. The last published estimates of the population put the total population at 127,000 in 1991.

Figure 2 Map of the Southern Ocean indicating the major southern elephant seal breeding islands.

VI. Breeding

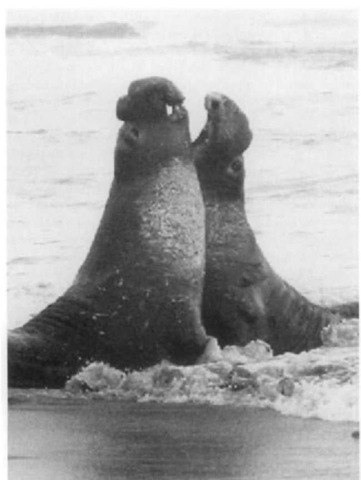

Both species of elephant seal are highly polygynous, with large, dominant males (alpha males) presiding over large aggregations of females, know as harems. Competition between males for the alpha position is intense and leads to spectacular fights (Fig. 4). Successful males will have almost exclusive access to harems consisting of up to 100 females, and so the reproductive benefits of success are very high. This has led to the evolution of the pronounced secondary sexual characteristics of immense body size and exaggerated proboscis.

Figure 3 Map of the West coast of North America indicating the major northern elephant seal breeding sites.

The annual breeding cycle begins when the largest males haul out on deserted beaches (in August for M. leonina and in December for M. angustirostris). Pregnant females then haul out in large numbers, aggregating into harems, and giving birth to their single pup 2-5 days after arriving. The females stay with their pup throughout the ensuing lactation period, never feeding and relying on their thick blubber layer to sustain them and to supply the many liters of milk required by the rapidly growing pup. At birth the pups weigh between 30 and 40 kg in both species, but by the time they wean, southern elephant seal pups weigh approximately 120-130 kg and northern elephant pups weigh approximately 140-150 kg. The difference in weaning weight is due to the slight difference in the duration of lactation in the two species, with southern elephant seals weaning at 23-25 days and northern elephant seals at 26-28 days.

Several days before weaning their pups, the females come into estrus and are mated by the dominant males. Although fertilization takes place at this time, the blastocyst does not implant until several months later. This ability, known as delayed implantation, is common to many pinnipeds. Once the pup is weaned, the females depart to sea, leaving the pups to fend for themselves. The pups spend the next 4 to 6 weeks teaching themselves to swim and hunt, during which time they rely heavily on the large reserves of blubber that they got from their mothers while suckling. When the pups eventually leave their natal beaches they spend the next 6 months at sea. This is a difficult time for the pups and as many as 30% of them die at this time.

Figure 4 Two adult male northern elephant seals fighting during the breeding season. Note the enlarged proboscis and predominant chest shields.

VII. Molt

Monachine seals all have an unusual annual molt, which entails the shedding of epidermal tissue in addition to the hair. The rich supplies of blood required at the body surface for the new skin and hair require the animals to leave the water in order to conserve body heat. The seals therefore spend 3-5 weeks fasting ashore during this time, once again relying on stored blubber to supply their energy requirements.

VIII. Behavior at Sea

Elephant seals spend more than 80% of their annual cycle at sea, feeding intensively to build up the blubber stores required to support them during breeding and molting haul outs. The seals prey on deep-water squid and fish and, as a result, have developed the remarkable ability to dive to depths in excess of 1500 m and for as long as 120 min. While these values are the extremes of those recorded, even the average values are impressive. Adult females routinely make dives of 20 min and reach depths of 400-800 m. Paradoxically, although the males generally dive for longer, about 30 min, they often do not go as deep. This is a reflection of their tendency to feed over continental shelves, whereas females use deeper open water. Seals spend as much as 90% of the time submerged, the majority of it hunting for food, but other behaviors, such as traveling from place to place, and apparently even resting, take place at depths of more than 200 m.