The term baleen (also called whalebone) is a mass noun that refers collectively to the series of thin keratinous – plates (“baleen plates”) that make up the filtering apparatus in the mouth of a baleen whale. The word derives from the classical Latin Balaena and ultimately from the Greek (j>dAoiivoi [phallaina], “whale.”

Baleen plates are suspended from the whale’s palate and are arranged in a row down each side of die mouth, extending from the tip of die rostrum back to the esophageal orifice. The left and right sides are separated by a prominent longitudinal ridge down the midline of the palate, but in the rorquals the two sides are continuous around the tip of the palate. Depending on die species, each “side” of baleen may contain anywhere betweeen 140 and 430 plates. The plates are transversely oriented and are spaced 1 or 2 cm apart, leaving a narrow gap or slot between adjacent plates. The plates are roughly triangular, with their horizontal basal edges embedded in the palate, their near-vertical labial edges facing outward, and their oblique, fringed lingual edges facing the inside of the mouth. Each plate is slighdy curved, with its convex side facing forward, so that its labial edge is directed slightly backward; when the whale is swimming forward, this arrangement helps direct the flow of water through the interplate gaps from the moudi cavity to die exterior side of die baleen row. The sizes of the plates are smoothly graded, with the longest ones half to two-thirds of die way back from the tip of the rostrum and only rudimentary ones at the anterior and posterior ends of the row (Williamson, 1973; Pivorunas 1976, 1979).

Each baleen plate is made up of a middle layer, the medulla, which is sandwiched between the thin, smooth outer layers or cortex. The medulla consists of a mass of fine, hollow, hair-like keratinous tubules that run parallel to the labial side of the plate and terminate along the lingual side; the tubules are embedded in and cemented together by a horny matrix.

Evoluntarily the plates were presumably derived by an elaboration of the transverse ridges present on the palates of many terrestrial mammals. In whale fetuses the baleen first appears as a series of crosswise ridges along each side of the palate. The palatial tissue of baleen whales is arranged in three layers. The basal layer, several centimeters thick, is the corium, This is overlain by a thin epithelial layer only a few millimeters thick. The outermost epidermal layer, several centimeters thick, is simply called the gum tissue. The corium gives rise to, and is continuous with, the medulla of each baleen plate, whereas the adjacent epithelial layer is deflected downward to produce the cortical layers of each plate. The dense, rubbery gum tissue does not contribute to the formation of the plates, but simply fills the spaces between their bases, where it provides them a firm support. As each plate grows downward, its cortical layers become cornified sooner than the medulla does. This leaves the first few centimeters of the base of the plate with a layer of soft, highly vascular, corial tissue sandwiched between the keratinous outer layers; this soft layer is often called the pulp, by analogy with the pulp in mammalian teeth (van Utrecht, 1965).

Throughout the life of the whale its baleen plates grow continuously at their base and wear away along their lingual margin. The cortex and the matrix of the medulla erode away first, freeing the ends of the fibrous tubules for a distance of about 10-20 cm. The freed tubules form a hairy fringe along the entire lingual side of the plate. The fringes of each plate lie back across the lingual edges of the plates immediately behind them, with the whole forming a dense hairy mat that covers the internal apertures to the gaps between the plates. This mat effectively filters out the food organisms while allowing the water to flow out of the whale’s mouth through the gaps.

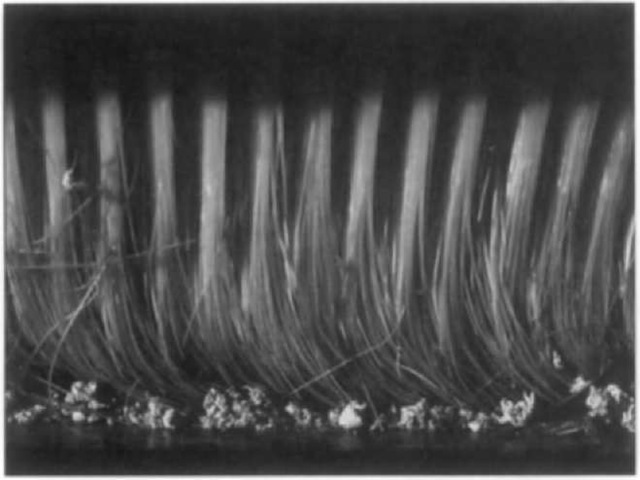

Figure 1 Baleen in whales such as the gray whale, Es-chrichtius robustus, is used to filter seawater for food. Notice the arrangement of these keratinous plates in rows.

Like human fingernails, the thickness of the baleen plates varies with the nutritional state of the whale. Alternating periods of summer gorging and winter fasting leave a regular series of visible growth zones on the surfaces of the plates. These zones have been used to infer the ages of whales, but because of the constant wear, it is rare for more than five or six zones to remain in a plate (Ruud, 1945). A claim that evidence of individual ovulations could be detected in the growth patterns of baleen plates was never confirmed (van Utrecht-Cock, 1965).

The number of baleen plates per side and their maximum size, shape, color, and other physical attributes are diagnostic for each species of whale. The right whales (family Balaenidae) with their narrow, highly arched rostrum have 250 to 390 narrow and extremely long plates, about 0.15-0.25 m wide and up to 2.50 m long in the black right whales (Eubalaena spp.) and 4.00 m in the bowhead whale (B. mysticetus); they are black with a fine whitish fringe. The pygmy right whale (Caperea nmrginata; family Neobalaenidae) has about 230 narrow, short plates up to 0.70 m long and 0.12 m wide; they are white with a black labial margin. The gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus; family Eschrichtiidae) has 140 thick but narrow and short plates, up to 0.10 m wide and 0.50 m long; they are white with a coarse white fringe that resembles excelsior (Fig. 1). The rorquals (family Balaenopteridae) with their wide, flat rostrum have 270 to 430 plates with a basal width 50 to 95% of their length, which varies from about 0.20 m in small minke whales to 1.00 m in huge blue whales. Each species of rorqual has a different color pattern on its baleen plates: humpback (Megaptera novaeangliae)—black with dirty-gray fringe; common minke (Balaenoptera acutorostrata)—white, sometimes with a narrow black stripe along labial margin; Antarctic minke (B. bonaerensis)—white with a wide black stripe along the labial margin; Bryde’s (B. edeni)—black with light gray fringe; sei (B. borealis)—black with fine, silky, white fringe; fin (B. physalus)—gray and white longitudinal bands, with fringe the same colors; and blue (B. musculus)—solid black with black fringe. All of the species of Balaenoptera, except the blue whale, usually have at least a few all-white baleen plates at the tip of the rostrum, mostly on the right side; this asymmetry is most prominent in the fin whale.

In the 19th century, the long baleen plates of the bowhead and right whales were much in demand for uses where a tough but limber material was needed so they were the most valuable product of the whale fishery. Landings of whalebone at United States ports reached their highest in 1853, with 5,652,300 pounds worth $1,950,000. The last year that any baleen reached the commercial market was 1930. Much of it was made into umbrella ribs, corset busks, and hoops for skirts. The fibrous fringes were used for brooms and brushes (Stevenson, 1907).