In This Chapter

Understanding the math behind gauge Getting your gauge on with some easy tips Taking steps for successful swatching Discovering drape and changing a pattern’s gauge, or tension, is at the heart of following a knitting pattern successfully. Even if you do everything else right, if you aren’t matching the gauge given, your project won’t turn out properly. If you want to knit something that actually fits anyone (or any part of anyone), take time to read and understand this chapter. I give you the knowledge you need for calculating gauge, tips for knitting to the correct gauge, and steps for making a swatch for any project.

Neither gauge nor tension sound quite like what they really are. Because of this confusion, some knitters fall into the “I don’t quite understand it, so I’m just going to ignore it” camp. And even though there are knitting directions that you can ignore without the universe collapsing (say, purl through the back loop), you can’t ignore gauge, unless you’re content with knitting wide floppy scarves and skinny pinheaded hats for the rest of your life.

Calculating Gauge for Any Project

Gauge refers to how many stitches and how many rows there are in 1 inch. It’s a precise way of measuring and describing how loosely or tightly something is knit. Often, gauge is described as the number of stitches and rows per 4 inches in a pattern or on a yarn’s label.

To figure out the number of stitches and rows you need in 1 inch, simply divide the listed gauge by four. For instance, a yarn with a gauge of 18 stitches and 24 rows per 4 inches is the same as 4.5 stitches per inch and 6 rows per inch. With these math skills, you’re sure to impress most third graders you know, but it’s okay to use a calculator if you need to.

The reason that gauge is so important is simple: Your gauge determines the size of whatever you’re knitting. Stitch gauge (the number of stitches per inch) is more critical than row gauge (the number of rows per inch) because the number of stitches determines the width of the piece. Once you cast on, your width is determined, and you can’t change it without starting over. Row gauge, on the other hand, determines the length of the piece. Matching row gauge precisely is less crucial because you can usually knit a couple more (or a couple less) rows to compensate and get the length you need.

To figure out how many stitches you need to cast on in order to make a piece that’s a certain width, use this formula:

Stitches per inch (stitch gauge) x width (in inches) = number of stitches

To figure out how wide something will be, use this formula (which is based on the previously formula):

Number of stitches stitches per inch (stitch gauge) = width (in inches)

To understand this math concretely, think of it in terms of a scarf. If you’re working with a yarn that knits to a gauge of 2.5 stitches per inch, and you want to make a scarf that’s 6 inches wide, simply multiply 2.5 by 6 for a total of 15 stitches. Voila! You now know how many stitches to cast on.

This scarf example is very simple, but the basic equation to calculate stitch gauge is at the root of every increase and decrease and every cast-on and bind-off in knitting. If you can plug numbers into this equation and solve it, you’re well on your way to your own basic design work. Even if you stick to knitting things designed by other people, this equation can help you understand what’s going on behind the scenes and can help you become better at deciphering patterns.

You can fill in Table 2-1 to practice this math and help you understand the difference that gauge makes. Note the range between the number of stitches you need to cast on with a super bulky yarn at a gauge of 2 stitches per inch and the number of stitches you need to cast on with a fine yarn at a gauge of 6 stitches per inch. You need three times as many stitches to knit the “same” scarf with a thinner yarn! (Flip to Chapter 1 to find out more about these and other types of yarn.) If you think for a moment about what this difference would mean over the width of a whole sweater, you can see why understanding gauge and being able to take the steps needed to match the gauge called for in a pattern is vital to your knitting happiness.

| Table 2-1 Cast-On Numbers for Scarves in Different Gauges Stitches per Inch x Width in Inches = Number of Stitches 2 6 2.5 6 3 6 3.5 6 4 6 4.5 6 5 6 5.5 6 6 6 |

How Tense Are You? Tips for Knitting to the Right Gauge

You know what gauge is and why matching a pattern’s recommended gauge is important. But what are you supposed to do about it? Read on to come to grips with getting the correct gauge.

Relaxing with your knitting

Knitters all vary in the way that they hold needles and move yarn. This variation means that with the same yarn and needles, different knitters will knit to different gauges. One may create a fabric that’s loose and see-through while another may make something that’s practically bulletproof. It’s important to recognize that matching the suggested gauge with the suggested needle size isn’t a sign of a good knitter; it’s only a sign of a knitter who happens to have similar tension to the person who made the pattern or packaged the yarn!

New knitters often ask whether they should change the way they hold the yarn or wrap it around their fingers or whether they should do something to snug up the yarn after each stitch. I always say no. Hold the yarn and needles so that you’re comfortable. As long as you’re making the stitches correctly, don’t try to correct your tension. Correcting your tension generally leads to overcorrection — and only part of the time! So, anything you do to make your stitches tighter or looser will likely change when you relax and get going. The end result will likely be worse, not better, because some spots will be looser and some spots tighter.

Knitting skills, just like all others, are improved with practice. So put in the time. Plan to spend 15 minutes a day with your knitting. Some days you may finish only a couple of rows, but other days you may find that once you pick up your knitting, you can’t put it down. By the time you come to the end of your first project, you’ll be able to see that your gauge has become much more even and consistent. And you’re probably enjoying it more too!

Switching needles if your gauge is off

Okay, so maybe you’re comfortable with your needles, and your gauge is more consistent, but it’s consistently off. Your stitches are too big and you’re getting 4 stitches per inch instead of 4.5. Big deal, you say. It’s close enough, right? Wrong! Unlike horseshoes and slow dancing, close doesn’t count in knitting. Here’s why: Imagine a sweater front that’s supposed to be knit at 4.5 stitches per inch. The directions say to cast on 90 stitches. The number of stitches on the needle, divided by the number of stitches per inch (or gauge) gives you the width of your knitting (for more about this formula, see the earlier section “Calculating Gauge for Any Project”). Here’s the filled-in equation:

90 stitches * 4.5 stitches per inch = 20 inches

From this equation, you determine that the sweater is 20 inches across. A quick study of the accompanying schematic confirms that this is how wide the sweater should be in the size that you want.

But at a gauge of 4 stitches per inch, what happens? Put the new gauge into the equation as follows to find out:

90 stitches * 4 stitches per inch = 22.5 inches

This math shows that the front of the sweater is 2.5 inches wider at the new gauge. That means the whole sweater will be 5 inches bigger around. That’s more than a whole size bigger!

With the following equation, you can see that you have equally ugly problems if your knitting is tighter than the suggested tension. If your gauge is 5 stitches to the inch rather than 4.5 stitches, here’s what happens:

90 stitches * 5 stitches per inch = 18 inches

The front of this sweater is 2 inches narrower than your intended size; the whole sweater will be 4 inches smaller around. Depending on the intended fit of the sweater, you may not even be able to get it on! Everything, including the ribbing around the neck, will be too tight.

I’ve heard many knitters say, “I’ll just follow the directions for the next smallest size.” This compensation for a loose gauge can work if you’re careful (very, very careful) in how you deal with the lengths of each piece, but you haven’t really fixed the problem with your stitches that are too big. The fabric you’re creating may simply not look right if your gauge isn’t correct.

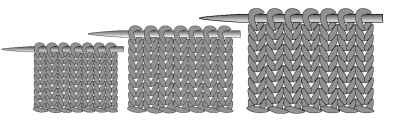

The real way to change the number of stitches that you knit in an inch is to change the needles that you’re using. A needle with a smaller diameter means that you make smaller loops when you wrap the yarn, and therefore you get smaller stitches. Likewise, bigger needles make bigger stitches. Check out the differences in Figure 2-1; the same yarn, stitch, and number of stiches are used, but the needle sizes and stitch sizes are different.

Figure 2-1:

Different needles yield different stitch sizes.

If your gauge is too tight, use bigger needles to correct the problem. If your gauge is too loose, use smaller needles to correct the problem. A lot of knitters get turned around on this point: If you have too many stitches per 4 inches, your gauge is too tight. If you have too few stitches, your gauge is too loose. You can see the difference that your needles make in gauge in the later section “Practicing different gauges in a single swatch.” (See Chapter 1 for details about all the types of needles available.)

Swatching Before You Begin a New Project

So how do you figure out what your gauge is for a particular project? You need to knit a little sample (called a swatch) and measure it. This process is called swatching. Sure, this takes a bit of time, but the results are absolutely worthwhile. “Take time to save time,” the old adage goes. By making a swatch, you’ll know that you’ve worked out the kinks in your gauge and that you’re armed with the right needles to knit a project that fits. (See Chapter 16 for some things you can do with your swatches.)

For most projects, you’ll likely need to try only a couple of needle sizes when you swatch. Plus, as you get to know yourself better as a knitter, you’ll be better able to predict your own gauge. Still, good knitters always swatch.

Making your swatch

Here’s how to make your swatch:

1. Begin by reading the gauge section at the beginning of your knitting pattern.

This section tells you how many stitches and rows you need to knit in 4 inches.

Here’s an example: “16 stitches and 20 rows per 4 inches over stockinette stitch on US 9 (5.5 mm) needles.”

2. With the needles listed and the yarn that you want to use, cast on at least 4 inches worth of stitches (see the appendix if you need a refresher on casting on).

The bigger your swatch, the more accurate your results, so it’s best to cast on about 6 inches worth of stitches. For the example in the previous step, that’s 24 stitches. (Why 24? 16 stitches divided by 4 inches equals 4 stitches per inch. Multiply 4 stitches per inch by 6 inches, and you wind up with 24 stitches.)

3. Begin knitting in the stitch pattern specified.

My example calls for stockinette stitch (see Chapter 5 for more about this stitch), but if the directions specify 2 x 2 rib or garter stitch, you must knit your swatch in that stitch pattern instead.

Whenever you make a swatch in stockinette stitch or some other stitch pattern that tends to roll, always knit the first and last 3 stitches of every row (even the purl rows) to create a garter stitch border. This makes measuring your swatch easier. Make sure you cast on a few extra stitches to accommodate this border, and measure the gauge between the borders.

4. Knit until the swatch measures 6 inches long and then bind off (see the appendix for more about binding off).

If you can tell after a couple of inches of knitting that your gauge is off (see the next section for the scoop on measuring your swatch), knit 1 wrong-side row to create a division between sections, change needle sizes, and continue knitting. You still need to knit a full-size swatch with the new needles, but you won’t have to cast on again and start over.

5. If you want your swatch to be as accurate as possible, take the added step of washing your swatch (or at least getting it damp) and allowing it to dry.

This step helps you figure out what your knit will look like after it’s washed. Some yarns don’t change much, but others can grow or shrink enough to make a difference. You wouldn’t want your sweater to fit only until you wash it and then find that it’s grown to an unflattering size! Check the ball band for information about how you should wash your swatch.

Measuring your swatch

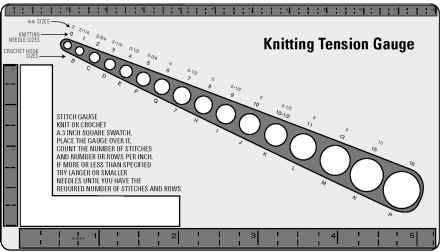

After you’ve made a swatch, it’s time to measure it. To do so, you need a ruler or gauge measurement tool (like the one shown in Figure 2-2) and a couple of straight pins. It’s important to make your swatch large enough (as I explain in the previous section) and to take it off the needles before you measure; the cast-on, the bind-off, or having the stitches still on the needle can skew your measurements and give you inaccurate results.

To measure your gauge from your swatch, follow these instructions:

1. Lay your swatch flat on the table.

Measuring on your knee or haphazardly in midair will throw off your numbers.

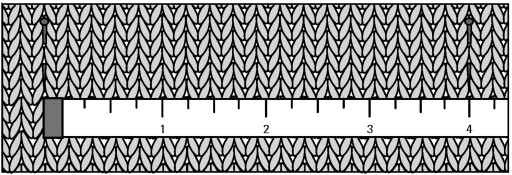

2. Place one straight pin vertically between two columns of stitches as shown in

Figure 2-3.

Don’t work too close to any of the edges, where the stitches may be more uneven.

Figure 2-2:

A handy device for checking gauge and needle size.

Figure 2-3:

Measuring your gauge.

3. Placing your ruler or gauge measurement tool parallel to a single row of stitches (at the bottom of the Vs), measure over 4 inches and place a second pin.

Pick up the ruler and put it down again to see if you still have 4 inches in between your pins. Many times, simply pushing the ruler down bends the fabric out of shape. You want to avoid this.

4. Count each stitch or V between the pins and write down the number.

Include any fractions of a stitch, and count again to make sure you have it right. Sometimes it’s helpful to use a pointer, like a spare double-pointed needle, to place on each stitch as you count.

5. When you’re satisfied that you’ve measured accurately, place your pins 4 inches apart at a different spot on your swatch and count again.

Are the numbers the same? If not, try a third spot and see what the results are. If the numbers vary a little, use the average of your measurements as your stitch gauge per 4 inches.

6. Repeat Steps 1 through 5 to measure your row gauge, this time placing your pins 4 inches apart horizontally and counting the number of rows in a single column of stitches.

When you’re finished measuring, compare the numbers you’ve written down to the gauge listed in the pattern. What counts as “matching” when it comes to gauge? When is “close” close enough? In the earlier section “Switching needles if your gauge is off,” I explain how the difference between 4 stitches per inch and 5 stitches per inch was equivalent to 9 inches or two whole sizes in a sweater, so, obviously, fractions count!

Gauge is normally given as a whole number per 4 inches. Gauge is reckoned to the nearest stitch per 4 inches, which translates to a quarter stitch per inch. So 4.4 stitches per inch is close enough to be considered correct for a gauge of 18 stitches per 4 inches (which boils down to 4.5 stitches per inch), but 4.2 stitches is not. If your swatch tells you that you’re off by more than a quarter of a stitch per inch, you haven’t found the right needles yet! Change your needles and start the swatching process over again until you get the right numbers.

Practicing different gauges in a single swatch

In this section, I show you a good way to practice getting your gauge on target. This gauge practice won’t really create any sort of useful or decorative object, but you can either keep the swatch as a reminder or rip it out and reuse the yarn when you’re done. If you don’t like those two options, make two or three of these swatches into a weird scarf. Or collect them from all your friends and make them into an artful quilt. Whatever you come up with, the process of making this swatch will be well worth your while.

The following statement is something that’s said only when you have to rip out half a sweater or reknit the sleeve (or something equally dreadful), but it’s still true and worth remembering: “Knitting is as much about the process as it is about the product.” Even something boring or goofy can be a pleasure to knit, simply because knitting is pleasant.

Okay, enough talk; it’s time to get started on the practice activity! Grab some yarn and needles in several sizes. You can do this with any yarn you have handy, but the numbers I use are based on worsted weight yarn (see Chapter 1 for more about this type of yarn). The manufacturer’s yarn label suggests knitting on US 7 (4.5 mm) needles to get a gauge of 20 stitches and 28 rows per 4 inches in stockinette stitch.

Follow these steps to practice assessing your gauge:

1. Cast on 30 stitches with US 4 (3.5 mm) needles, and then knit 6 rows in garter stitch to prevent the edge from rolling.

Remember, always knit the first and last 3 stitches of every row (even the purl rows) if you’re working in stockinette stitch or some other stitch pattern that tends to roll at the edges. This creates a narrow garter stitch border and makes measuring easier.

2. Work 4 inches in stockinette stitch (or the stitch pattern that your pattern calls for).

3. Knit 1 wrong-side row to create a division between sections.

4. Switch to needles one size larger — US 5 (3.75 mm) needles — and then work 4 more inches in your stitch pattern.

5. Make another dividing line and switch to US 6 (4 mm) needles, and then work 4 more inches.

6. Continue making 4-inch sections, moving up one needle size each time, going up all the way to US 13 (or larger, if you can stand it).

7. Finish your sampler by working 6 rows in garter stitch and then binding off.

As you work this piece, the one thing you’ll notice right away is that one end of your swatch is much wider than the other. What you’re seeing is the difference that gauge can make. Measure your stitch gauge for each section (I explain how to do so earlier in this chapter). Chances are a couple of your sections will be good contenders for matching the suggested stitch gauge for the yarn that you’re working with. To decide between these needle sizes, measure your row gauge in these sections and choose the one that most closely matches the specified row gauge.

Checking Your Gauge throughout a Project

The previous section walks you through the elements of making and measuring a gauge swatch. In truth, however, you need to be mindful of your gauge throughout the entire knitting process (at least on projects that are supposed to fit a certain way). In the following sections, I show you when and how to check your gauge throughout a project.

For something that doesn’t need to fit exactly, like a scarf or a wrap, you don’t need to be nearly as fastidious. If it looks good to you, you don’t need to fret about the numbers.

When to check your gauge

After you’ve cast on and knit a couple of inches of your project, measure your gauge again to see how it’s going (see the next section for the how-to). If you made and measured your swatch a month ago or even a week ago, things may have changed. Your mood, level of alertness, or the fact that you’ve been knitting more or less often can all affect your knitting tension. Or maybe you swatched on straight wooden needles and now you’re knitting with metal circular needles. The material a needle is made of can make a big difference to your gauge.

Check your gauge from time to time as you work on your project, particularly if you have put it aside for a while and have just recently come back to it. If you get in the habit of checking your gauge when you have a tape measure out to determine the length of your knitting, it won’t seem like any extra work.

After you verify that you’re on the right track with your gauge, you can continue knitting with confidence. It’s much easier to rip out a few inches than it is to rip out the whole back when you discover that your gauge is off. And knitters, like everyone else, are often loath to admit their mistakes. If you have a gnawing sense that something isn’t quite right, force yourself to do the necessary reality check and measure things. The sooner you correct an error, the better.

How to check your gauge

To check gauge during a project, many knitters like to use a gauge measurement tool. This tool has holes to size up needles and a small window that’s 2 inches wide and 2 inches tall (refer to Figure 2-2). To use the gauge measurement tool, lay your knitting flat and, without pressing it down so vigorously that you distort the stitches, lay your gauge meter on top and count how many stitches there are across the window. Don’t forget that you have to double the number of stitches to determine the number of stitches per 4 inches.

You can also use a tape measure or ruler to help you count the number of stitches per 4 inches. I have a lightweight clear plastic ruler that works nicely.

Whatever tool you’re using, be sure that your knitting is flat on a table and that your measuring device is lying parallel to your rows of stitches.

You might grab a current project or a few knits from the closet (whether they’re hand-knit or store-bought) and take a few minutes to practice measuring gauge. Try measuring in different places, over different stitch patterns (like stockinette stitch or ribbing), or even with different tools to get comfortable with taking these measurements.

Examining the Drapes of Different Gauges

The patterns in this topic (and knitting patterns in general) specify a certain yarn and a certain gauge. When you use the yarn suggested by the designer, you’re pretty much set because she or he has done most of the behind-the-scenes work for you. But sometimes you won’t be able to easily find the yarn called for. And other times you may want to knit with another fiber or use up some yarn that you already have. You can and should experiment — this is how you create things that are unique and exactly what you want.

The gauge on the yarn label is a typical gauge for that yarn. But remember, that number is just someone’s opinion, not the gospel truth! So, if you find that you prefer the fabric that the yarn makes when it’s knit looser or tighter, that’s okay. You should also remember that the listed gauge is also based on certain assumptions about what you’ll be knitting. The manufacturer doesn’t know whether you’re knitting a sock or a stole. A mitten that’s meant to keep out snow will require a denser fabric and a tighter gauge than a lacy scarf. So, it’s worth exploring gauge not just in absolute numbers, but in terms of the “hand” or “drape” of the fabric that you’re making (how the fabric feels or where it falls on a continuum from stiff to floppy). This way you can choose the right yarn and the right gauge for what you want to make.

To get a handle on gauge and drape, get out the gauge sampler that you made in the earlier section “Practicing different gauges in a single swatch.” Or, at the very least, grab an armful of knitted objects and have a close look at them while keeping the following considerations about drape and gauge in mind:

You’ll notice that on the smallest needles, the fabric is very dense. Maybe you’ve knit 23 stitches and 32 rows per 4 inches with worsted weight yarn. Hold the fabric in your hand and notice that it’s quite stiff. You can’t see through it at all, and it doesn’t follow the shape of your hand. For almost any purpose, this gauge is just too tight. I call this a bulletproof fabric. It may be okay for a mitten or a purse that’s meant to hold its shape, but I bet you also noticed that it wasn’t much fun to knit. Just because it’s possible to knit this tight doesn’t mean that you should. If you want something this dense, try felting instead. (Find out how to felt in the appendix; or try out the potholders in Chapter 9 for a quick introduction to this fun technique.)

If you’re trying to substitute yarns and the fabric that you make ends up in the bulletproof category when knit at the gauge called for in the pattern, it isn’t the right yarn for the job. In this case, you need to find a thinner yarn for the project.

When moving up in gauge to somewhere between 21 and 22 stitches per 4 inches, your fabric is still pretty dense, but it moves a little more readily. With this sort of fabric, you probably would knit something like a mitten, or maybe a structured hat or a cushion cover. The piece won’t be floppy at all and will insist on keeping its own shape rather than following the lines of the body. Most projects will be more pleasing if they’re knit at a looser gauge than this. A sweater won’t look its best if it’s knit too tightly.

When you get to the gauge recommended for the yarn (20 stitches per 4 inches in the gauge sampler), you’ve hit your happy medium. You’ll notice that you can see a bit of light through it when you hold it up. And when you put it on your hand, it moves to follow the shape of your hand, but it isn’t see-through. This fabric is perfect for things like sweaters because even though you want the fabric to drape on your body, you also don’t want your skin to show through.

At a gauge somewhere between 16 and 18 stitches per 4 inches, you’ll definitely be able to see light through the swatch and maybe even some skin. The fabric drapes easily. Many accessories that are meant to be less structured and show some movement, such as a scarf, poncho, or wrap, are great when knit at this gauge.

With larger needles still, the stitches are very large. In this case, the knitted fabric is as much about the light and air between the stitches as it is about the yarn that surrounds these holes. This very open gauge is what you want for something like the multiyarn stole in Chapter 8 or the lacy shawl in Chapter 12.

Whatever type of garment you’re making, think a bit about what sort of drape and fabric suits it best when determining whether your gauge is right on target. Any yarn can be knit at a variety of gauges, as the gauge sampler demonstrates. But getting gauge right also means making a more subjective judgment about whether you like the fabric you’ve knit and whether you think that it’s right for the project that you want to make. Chapter 1 has full details on selecting the right yarn for any project at any gauge.