Beekeeping

Beekeeping is the establishment and tending of colonies of social bees of any species, an activity from which the beekeeper obtains a harvest or reward. This reward is usually honey, but it may be some other bee products, or bees themselves (e.g., queens, or colonies for pollination). In beekeeping, each colony is usually in a hive, but some beekeeping is done with honey bees that build their nests in the open. Beekeeping is also done with certain nonsocial bees that are reared for pollinating crops.

TECHNIQUES OF MODERN MOVABLE-FRAME

HIVE BEEKEEPING WITH APIS MELLIFERA

Most of the world’s beekeeping is done with A. mellifera. In past centuries, these bees were kept primarily for the production of honey and beeswax. Beekeeping is still done mainly to produce honey, but there are also other specialized types of operation. These include the rearing of queens or package bees for other beekeepers who are producing honey. Another type of beekeeping provides colonies of bees to pollinate crops, since in many areas of large-scale agriculture the native pollinators have been destroyed. Since the 1950s specialized beekeeping has also been developed for the production of royal jelly, pollen, and bee venom.

Each type of beekeeping requires the management of colonies to stimulate the bees to do what the beekeeper wants—for instance, to rear more young house bees to produce royal jelly, or more foragers to pollinate crops. During the 1900s, effective methods were developed for the commercial production of substances other than honey: bee brood, bee venom, beeswax, pollen, propolis, and royal jelly.

Honey Production

A colony of honey-storing bees collects nectar from which it makes honey. Nectar is not available continuously, and to store much honey a colony of bees needs many foraging bees (over, say, 10 days old) whenever a nectar “flow” is available within their flight range. Bees may fly 2 km if necessary, but the greater the distance, the more energy they expend in flight, and the more nectar or honey they consume. Thus, it is often cost-effective for the beekeeper to move hives to several nectar flows in turn during the active season.

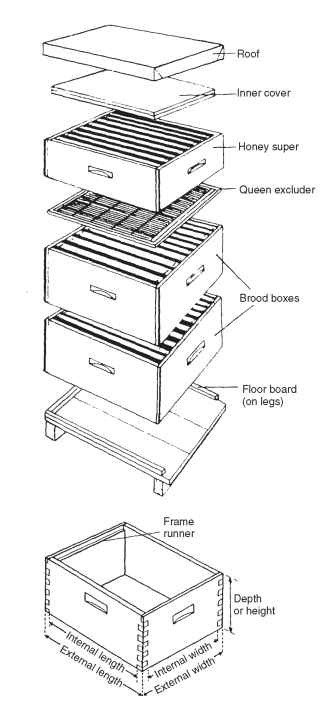

Figure 1 shows a movable-frame hive with two ” deep” boxes. The hive in Fig. 2 also has two deep boxes for brood (i.e., immature bees, eggs, larvae, and pupae), and a shallow box for honey that is less heavy to lift. Any number of honey boxes (also called supers) may be added to a hive, but these are always separated from the brood boxes by a queen excluder, to keep the honey free from brood. Some empty combs in these supers may stimulate honey storage, but supers are not added far in advance of their likely use by the bees.

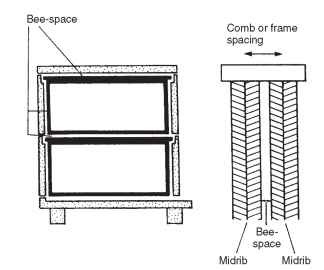

It is essential that hives and frames have standard dimensions and that an accessory (spacer) is used to ensure that frames are always exactly the correct distance apart.

FIGURE 1 Vertical section through a movable-frame hive, showing a brood comb in each box, and the bee spaces.

FIGURE 2 Top: exploded view of a movable-frame hive showing the component parts. Bottom: empty hive box showing one of the frame runners.

Queen Production

Large-scale operations are done in five steps, which provide specific conditions for the successive developmental stages of the immature bees that will develop into mated and laying queens.

1. The larvae from which queens will be reared are taken from worker cells of a colony that is headed by a breeder queen selected for chosen genetic characters.

2. Very young larvae are transferred into cell cups mounted mouth down on wooden bars in a “cell-starter colony” that has been queenless for 2-4 h. This colony is made up of many (young) nurse bees, and little or no other brood for them to rear. Its bees build the cell cups further and feed the young larvae, and the colony can “start” the rearing of 45-90 queen larvae a day.

3. As the larvae grow larger, they receive more food and are better cared for if the number of nurse bees per larva is high. So it is usual to put about 15 cells in each of a number of colonies, where they are separated from the colony’s queen by a queen excluder.

4. When the bees have finished feeding the larvae, they seal each immature queen in her cell. The only requirements of an immature queen during the next 7 days are appropriate conditions of temperature and humidity, and these are provided in an incubator. Each queen must emerge from her cell as an adult in a separate cage, for protection from attacks by other queens already emerged.

5. Finally, each queen is placed in a “mating hive” containing a few hundred or more workers but no other queen. These hives are taken to a mating apiary, which contains a few strong colonies that include many drones (i.e., males) of a selected strain of honey bees. The apiary is located as far as possible from hives that might contain other drones; a distance of 15 km is likely to be safe, but it varies according to the terrain. When the queen is a few days old, she flies out and mates with drones, and a few days later starts to lay eggs. This shows that she is ready to head a colony.

Package Bee Production

The term “package bees” is used for a number of young worker bees (usually approximately 1 kg) hived with a newly reared and mated queen; these bees together have the potential to develop into a honey-producing colony.

Package bees are normally produced at relatively low latitudes where spring comes early, and are sold at higher latitudes where it is difficult to keep colonies over the winter; many northern beekeepers find it more cost-effective to kill some or all of their colonies when they harvest the season’s honey, and to buy package bees next spring. (If they have no colonies over the winter, they can follow another occupation for 6 months or more; at least one beekeeper spends the Canadian winter beekeeping in New Zealand, where it is then summer.) The site where the packages are produced should be earlier weather-wise, by 2 months or more, than the site where the bees are used. A package bee industry is most likely to be viable where a single country stretches over a sufficient north-south distance (at least 1000 km, and up to 2000 or even 2500 km). But in New Zealand, package bees are produced at the end of the bees’ active season and sent by air to Canada, where the season is just starting.

Package bees are prepared as follows. First, all the bees are shaken off the combs of three or four colonies into a specially designed box, taking care that the queens are left behind. The bees are then poured through the “spout” of the box into package boxes, each standing on a weighing machine, until their weight is either 1 or 1.5 kg, as required. Each box is given a young mated queen in a cage, and a can of syrup with feeding holes. (Enough bees fly around to return to their hives and keep the colonies functional.) For transport, the package boxes are fixed by battens in groups of three or four, slightly separated; they may travel 2400 km, and the truck needs special ventilation. Air transport, though possible, presents various difficulties.

Crop Pollination

Colonies taken to pollinate crops should be strong, with many foraging bees, much unsealed brood (to stimulate the bees to forage for pollen), and space for the queen to lay more eggs. Hives should not be taken to the crop before it comes into bloom, otherwise the bees may start foraging on other plants and continue to do so when the crop flowers. If the hives are in a greenhouse, four to eight frames of bees in each may be sufficient, but the beekeeper must check regularly that the bees have enough food; alternatively, each hive may be provided with two flight entrances, one into the greenhouse and one outside. Beekeepers who hire out hives of bees for crop pollination need to have a sound legal contract with the crop grower; they should also be aware of the risks of their bees being poisoned by insecticides.

In addition to honey bees, certain native bees are especially efficient in pollinating one or more crop species, and several species are managed commercially for pollination. The following species are quite widely used for the crops indicated: Andrena spp. for sarson and berseem in Egypt and India; Bombus spp. for tomato and red clover in Finland and Poland; Megachile spp. for alfalfa in Chile, India, South Africa, and the United States; Nomia melanderi for alfalfa in the United States; Osmia spp. for alfalfa in France; and Xenoglossa spp. for apple in Japan, Poland, and Spain, also for cotton and curcurbits in the United States.

Special Features of Beekeeping in the Subtropics and Tropics

The subtropics (between 23.5″ and 34°N, and 23.5° and 34°S) include some of the most valuable world regions for honey production. Like the temperate zones, they have an annual cycle with a distinct seasonal rhythm and a well-marked summer and winter; however, the climate is warmer and the winters are mild, so the bees can fly year-round. All the major honey-exporting countries include a belt within these subtropical latitudes: China, Mexico, Argentina, and Australia.

Between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn (23.5°N and 23.5°S), the situation is different. The seasons (and honey bee colonies) undergo two cycles in the year because the noonday sun is overhead twice a year. So colonies do not generally grow as large as at higher latitudes, nor do they store as much honey. When forage becomes scarce, a colony may cease brood rearing and then fly as a unit to a nearby area where plants are coming into bloom; this flight is referred to as absconding or migration. So one beekeeper in an area may lose colonies, while other beekeepers in the other area may put out bait hives to receive the swarms.

Beekeeping in the tropics using traditional hives has been well studied, and many development programs have been carried out to introduce more advanced methods. Francis Smith pioneered successful movable-frame hive beekeeping in tropical Africa.

In the tropics, bee diseases are of less importance than at higher latitudes, but bees in torrid zones may be subject to attack by more enemies, certain birds, mammals, and insects. Tropical honey bees therefore defend their nests more vigorously than temperate-zone honey bees. For instance, tropical African honey bees (A. mellifera) are easily alerted to sting and, as a result of rapid pheromone communication between individuals, they may attack en masse. People in tropical Africa have grown up with the bees and are accustomed to them. But after 1957, when some escaped following introduction to the South American tropics, they spread into areas where the inhabitants had known only the more gentle European bees, and those from tropical Africa were given the name “killer bees.” But once beekeepers in South America had learned how to handle the new bees, they obtained much higher honey yields than from the European bees used earlier.

OTHER ASPECTS OF MODERN HIVE BEEKEEPING

World Spread of A. mellifera

In the early 1600s, the bees were taken by sailing ship across the Atlantic from England to North America. They would have been in skeps (inverted baskets made of coiled straw), which were then used as hives. The first hives were probably landed in Virginia. The bees flourished and spread by swarming, and other colonies were taken later. By 1800 there were colonies in some 25 of the areas that are now U.S. states, and by 1850 in a further 7. The bees were kept in fixed-comb hives (skeps, logs, and boxes).

The bees may possibly have been taken from Spain to Mexico in the late 1500s, but they reached other countries later: for example, St. Kitts-Nevis in 1720, Canada in 1776, Australia in 1822, and New Zealand and South America in 1839. They were taken later to Hawaii (1857) and Greenland (1950).

In Asian countries where Apis cerana was used for beekeeping, A. mellifera was introduced at the same time as movable-frame hives. Some probable years of introduction were 1875-1876 in Japan, 1880s in India, 1896 in China, and 1908 in Vietnam.

Between 1850 and 1900, there was widespread activity among beekeepers in testing the suitability of different races of A. mellifera for hive beekeeping. The most favored race was Italian (A. m. ligus-tica), named from Liguria territory on the west coast of Italy, south of Genoa.

Origination and World Spread of Movable-Frame Beekeeping

The production of a movable-frame hive divided the history of hive beekeeping into two distinct phases. This new hive type was invented in 1851 by Reverend Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth in Philadelphia. He was familiar with the Greek movable-comb hive (discussed later under Traditional Movable-Comb Hive Beekeeping) and with some rectangular hives devised in Europe that contained wooden frames for the bees to build their combs in. These hives, however, had only a very small gap between the frames and the hive walls, and the bees built wax to close it. In 1853, Langstroth described how he had often pondered ways in which he “could get rid of the disagreeable necessity of cutting the attachments of the combs from the walls of the hives.” He continued, “The almost self-evident idea of using the same bee space (as between the centerlines of combs in the frames) in the shallow (honey) chambers came into my mind, and in a moment the suspended movable frames, kept at a suitable distance from each other and from the case containing them, came into being.” Framed honey combs were harvested from an upper box, and the brood was in the box below. A queen excluder between the boxes prevented the queen from laying eggs in the honey chamber.

The use of hives based on Langstroth’s design spread rapidly around the world, dimensions often being somewhat smaller in countries where honey yields were low. Some years of their first known introduction are 1861, United Kingdom; 1870, Australia; 1878, South Africa; 1880s, India; and 1896, China.

Beekeeping with A. cerana in Movable-Frame Hives

Bees of most races of A. cerana are smaller than A. mellifera; they also build smaller colonies and are less productive for the beekeeper.

Unlike A. mellifera, A. cerana does not collect or use propolis. A. cer-ana was the only hive bee in Asia until A. mellifera was introduced in the late 1800s; it had been kept in traditional hives (logs, boxes, barrels, baskets, pottery) since the first or second century A.D. in China and probably from the 300s B.C. in the upper Indus basin, now in Pakistan.

The movable-frame hives used for A. cerana are like a scaled-down version of those for A. mellifera. Colony management is similar, except that the beekeeper needs to take steps to minimize absconding by the colonies. In India, 30-75% of colonies may abscond each year. To prevent this, a colony must always have sufficient stores of both pollen and honey or syrup, and preferably a young queen. Special care is needed to prevent robbing when syrup is fed. Colonies must also be protected against ants and wasps.

The bees at higher latitudes are larger, and in Kashmir (altitude 1500 m and above) A. cerana is almost as large as A. mellifera and fairly similar to it in other characteristics; for instance, the colonies do not abscond.

Honey Bee Diseases, Parasites, Predators, and Poisoning

The main brood diseases of A. mellifera, with their causative organisms, are American foulbrood (AFB), Paenibacillus larvae; European foulbrood (EFB), Melissococcus pluton; sacbrood, sacbrood virus (Thai sacbrood virus in A. cerana); and chalkbrood, Ascosphaera apis. Diseases of adult bees are nosema disease, Nosema apis; amoeba disease, Malpighamoeba mellificae; and virus diseases. Parasites are tracheal mite, Acarapis woodi; varroa mites, Varroa jacobsoni and V. destructor; the mite Tropilaelaps clareae; bee louse (Diptera), Braula spp.; and the small hive beetle, Aethina tumida.

Disease or parasitization debilitates the colonies, and diagnosis and treatment require time, skill, and extra expense. Most of the diseases and infestations just listed can be treated if colonies are in movable-frame hives, and in many countries bee disease inspectors provide help and advice. Colonies in fixed-comb hives and wild colonies cannot be inspected in the same way, and they can be a long-term focus of diseases. But by far the most common source of contagion is the transport into an area of bees from elsewhere.

The parasitic Varroa mite provides an example. It parasitized A. cerana in Asia, where the mite and this bee coexisted. In the Russian Far East, it transferred to introduced A. mellifera, whose developmental period is slightly longer, allowing more mites to be reared. Because colonies could then die from the infestation, the effects were disastrous. In the mid-1900s, some infested A. mellifera colonies were transported to Moscow; from there, mites were unwittingly sent with bees to other parts of Europe, and they have now reached most countries in the world.

Since the 1950s it has been increasingly easy to move honey bees (queens with attendant workers, and then packages of bees) from one country or continent to another. One result has been that diseases and parasites of the bees have been transmitted to a great many new areas, and to species or races of honey bee that had little or no resistance to them.

The development of large-scale agriculture has involved the use of insecticides, many of which are toxic to bees and can kill those taken to pollinate crops. In California alone, insecticides killed 82,000 colonies in 1962; in 1973 the number was reduced to 36,000, but in 1981 it had risen again, to 56,000. More attention is now paid to the use of practices that protect the bees, including selecting pesticides less toxic to beneficial insects, using pesticides in the forms least toxic to honey bees (e.g., granular instead of dust), spraying at night when bees are not flying, spraying only when the crop is not in flower, and using systemic insecticides and biological pest control. Possible actions by the beekeeper are less satisfactory: moving hives away from areas to be treated, or confining the bees during spraying by placing a protective cover over each hive and keeping it wet to reduce the temperature.

By 1990, legislation designed to protect bees from pesticide injury had been enacted in 38 countries, and a further 7 had established a code of practice or similar recommendations.

TRADITIONAL FIXED-COMB HIVE BEEKEEPING

A. mellifera in the Middle East, Europe, and Africa

Humans have been obtaining honey and wax from bees’ nests in the Middle East, Europe, and Africa since very early times. Beekeeping with A. mellifera was probably initiated in an area when the human population increased so much that it needed more honey or wax than was available at existing nest sites, or when some change occurred that reduced the number of nest sites—for instance, when trees were felled to clear land for agriculture.

In the Middle East, population increase was linked with the development of civilizations. The earliest known hive beekeeping was done in ancient Egypt, and similar traditional beekeeping is still carried out in Egypt. In Abu Ghorab, near Cairo, an Old Kingdom bas-relief from around 2400 B.C. shows a kneeling beekeeper working at one end of hives built into a stack; smoke is used to pacify the bees, and honey is being transferred into large storage pots. Over time, the use of horizontal cylindrical hives spread throughout the Mediterranean region and Middle East, and also to tropical Africa, where hollow log hives were often fixed in trees, out of reach of predators.

In the forests of northern Europe, where honey bees nested in tree cavities, early humans obtained honey and wax from the nests. When trees were felled to clear the land, logs containing nests were stood upright on the ground as hives. As a result, later traditional hives in northern Europe were also set upright. In early types such as a log or skep, a swarm of bees built its nest by attaching parallel beeswax combs to the underside of the hive top. If the base of the hive was open as in a skep, the beekeeper harvested honey from it. Otherwise harvesting was done from the top if there was a removable cover, or through a hole previously cut in the side.

Skeps used in northwestern Europe were made small so that colonies in them swarmed early in the active season; each swarm was housed in another skep, and stored some honey. At the end of the season, bees in some skeps were killed with sulfur smoke and all their honey harvested; bees in the other skeps were overwintered, and their honey was left as food during the winter.

A. cerana in Asia

In eastern Asia the cavity-nesting honey bee was A. cerana, and it was kept in logs and boxes of various kinds from A.D. 200 or earlier. But farther west in the upper Indus basin, horizontal hives rather similar to those of ancient Greece are used, and it has been suggested that hive beekeeping was started in the 300s B.C. by some of the soldiers of the army of Alexander the Great, who settled there after having invaded the area.

Stingless Bees (Meliponinae) in the Tropics

In the Old World tropics, much more honey could be obtained from honey bees than from stingless bees, and the latter were seldomused for beekeeping. But in the Americas, where there were no honey bees, hive beekeeping was developed especially with the stingless bee, Melipona beecheii, a fairly large species well suited for the purpose. It builds a horizontal nest with brood in the center and irregular cells at the extremities, where honey and pollen are stored. The Maya people in the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico still do much beekeeping with this bee. The hive is made from a hollowed wooden log, its ends being closed by a wooden or stone disk. To harvest honey, one of the disks is removed to provide access to honey cells; these are broken off with a blunt object, and a basket is placed underneath the opening to strain the honey into a receptacle below. Many similar stone disks from the 300s B.C. and later were excavated from Yucatan and from the island of Cozumel, suggesting that the practice existed in Mexico at least from that time.

Nogueira-Neto in Brazil developed a more rational form of beekeeping with stingless bees. In Australia, the native peoples did not do hive beekeeping with stingless bees, but this has recently been started.

TRADITIONAL MOVABLE-COMB HIVE BEEKEEPING

Movable-comb hive beekeeping was a crucial intermediate step between fixed-comb beekeeping, which had been done in many parts of the Old World, and the movable-frame beekeeping used today.

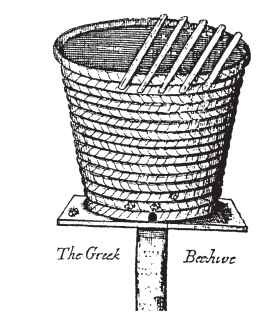

In a topic published in 1682 in England, Sir George Wheler recounted his journeys in Greece and provided details of the hives he saw there (Fig. 3). He described the wooden bars shown lying across the top of the hive as “broad, flat sticks” and said that the bees built a comb down from each top bar, which “may be taken out whole, without the least bruising, and with the greatest ease imaginable.” So it was a movable-comb hive. The Greek beekeepers must have placed the bars at the bees’ natural spacing of their combs. They made a new colony by putting half the bars and combs from a hive into an empty one; the queen would be in one of the hives, and the bees in the other would rear a new queen.

FIGURE 3 Sir George Wheler’s drawing of a Greek top-bar hive.

In the mountain range that separates Vietnam from China, some of the native peoples use a movable-comb hive for A. cerana; it is not known how old is this method of beekeeping. The bars are fitted across the top of a log hive at the correct spacing for A. cerana. This bee builds small combs without attaching them to the hive sides, and the combs can be lifted out by their bars. There seems to have been no development of a movable-frame hive from this movable-comb hive for A. cerana.

TRADITIONAL BEEKEEPING WITHOUT HIVES

Apis dorsata

In tropical Asia, a nest of the giant honey bee, A. dorsata, which is migratory, can yield much more honey than a hive of A. cerana. In a form of beekeeping with A. dorsata practiced in a few areas, people use horizontal supports called “rafters” instead of hives. (A “rafter” is a strong pole, secured at a height convenient for the beekeeper by a wooden support, or part of a tree, at each end.) At the appropriate season, beekeepers erect rafters in a known nesting area for migratory swarms of the bees. Sheltered sites with an open space around one end are chosen, which the bees are likely to accept for nesting. After swarms have arrived and built combs from the rafters, the beekeeper harvests honey every few weeks by cutting away part of the comb containing honey but leaving the brood comb intact. When plants in the area no longer produce nectar, brood rearing ceases and the bees migrate to another site.

Apis florea

The small honey bee, A. florea, builds a single brood comb perhaps 20 cm high, supported from the thin branch of a tree or bush. It constructs deeper cells round the supporting branch and stores honey in them. The whole comb can easily be removed by cutting through the branch at each side, and in some regions combs are then taken to an apiary where the two ends of each branch are supported on a pile of stones or some other structure. This is done, for instance, in the Indus basin near Peshawar in Pakistan, and on the north coast of Oman.

RESOURCES FOR BEEKEEPERS

There are various sources of information and help for beekeepers. Many countries publish one or more beekeeping journals, and have a beekeepers’ or apiculturists’ association with regional and local branches. Apimondia in Rome, Italy (http://www.apimondia.org), is the international federation of national beekeepers’ associations.

In many countries, the ministry of agriculture or a similar body maintains a bee department that inspects colonies for bee diseases and often also provides an advisory service for beekeepers. Research on bees and/or beekeeping may be carried out under this ministry or by other bodies.

The International Bee Research Association in Cardiff, the United Kingdom, serves as a world center for scientific information on bees and beekeeping, and publishes international journals, including Apicultural Abstracts, which contains summaries of recent publications worldwide. Information about access to the Association’s data banks can be obtained from its Web site which is linked to Ingenta.