INTRODUCTION

Between 1997-2003, Internet hosts grew from 16 million to over 233 million worldwide (www.isc.org, 2004). Of all Internet hosts, the number of commercial domain names (.com) is about 20.9%, which increased from 3.9 million in January 1997 to 48.6 million in January 2004.

Despite continued market growth, a number of Web sites have been unprofitable. From 2000 to 2003, at least 962 Internet companies ran out of money, shut down their operation and sold their businesses, with 63 5 of these enterprises operating in the business-to-consumer (B2C) sector (www.webmergers.com, 2004). Some notable failures were eToys.com, boo.com, bluefly.com, buy.com and valueamerica.com. An examination of the companies’ IPO filings suggests that the collapses were caused by cut-price strategies, over-investment, incorrect expectations, and non-profitability. The surviving dot com companies in the new economy also have experienced financial difficulties. Amazon, a member of the Internet hall of fame, is still unable to generate a profit (www.webmergers.com (2004) REPORT). Surviving in the digital market has become a critical challenge for Web managers.

To face the business challenge, Web managers and marketers demand information about Web site design and investment effectiveness (Ghosh, 1998). Further, as the rate and diversity of product/service innovation declines and competition intensifies, Web managers must increase their efforts to improve their product/service and stabilize market shares. In this context, Donath (1999) and Hoffman (2000) noted the lack of, and the need for, research on Internet-related investment decisions. Web managers and marketers would benefit from reliable and consistent measuring tools for their investment decisions, and such tools are the focus of this article.

BACKGROUND

Since online consumers can switch to other Web sites or competitive URLs in seconds with minimal financial costs, most Web sites invest heavily in programs to attract and retain customers. The Web site’s ability to capture consumers’ attention is known widely as “stickiness”.

From one perspective (Rubric, 1999, p. 5), “The sticky factor refers to the ability of a web site to capture and keep a visitor’s attention for a period of time.” Likewise, stickiness can be described as the ability of the site in attracting longer and more frequent repeat visits or the ability of the site to retain customers (Anders, 1999; Davenport, 2000; Hanson, 2000; Murphy, 1999; O’Brien, 1999; Pappas, 1999). The various perspectives suggest that stickiness is similar to, if not the same concept as, customer loyalty.

On the other hand, Demers and Lev (2000) distinguished stickiness from customer loyalty. In their research, stickiness is represented by the average time spent at the site per visit, and customer loyalty refers to the frequency of visits. In fact, both the time duration and frequency of visits are mutually inclusive. The extension of the duration of relationships with customers is driven by retention (Reichheld, 1996). Loyal customers would visit the Web site frequently and remain with the site for a longer time period. In the process, these customers are generating not only traffic but revenue as well. Therefore, the goal of any Web site stickiness program must be to make customers loyal.

Customer loyalty has been a core element of marketing since the early eighties (Morgan & Hunt, 1994). The idea is to develop and maintain long-term relationships with customers by creating superior customer value and satisfaction. Enhanced customer satisfaction results in customer loyalty and increased profit (Anderson, Fornell & Lehmann, 1994; Reichheld & Sasser, 1990). Loyal customers, who return again and again over a period of time, also are valuable assets of the Web site. The ability to create customer loyalty has been a major driver of success in e-commerce (Reichheld & Schefter, 2000; Reichheld et al., 2000) since enhanced customer loyalty results in increased long-term profitability.

From marketing theory, then, stickiness can be viewed as the ability of a Web site to create both customer attraction and customer retention for the purpose of maximizing revenue and profit. Customer attraction is the ability to attract customers at the Web site, whereas customer retention is the ability to retain customer loyalty.

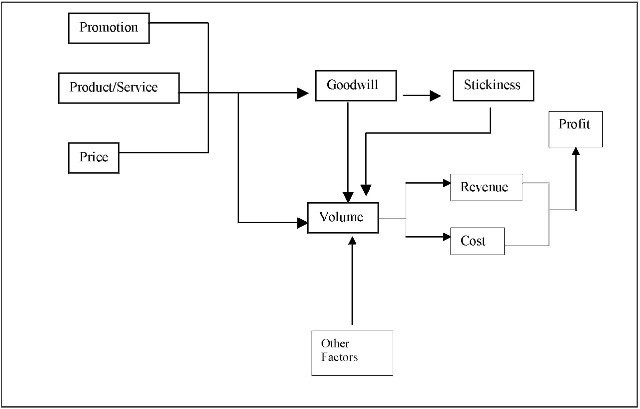

Figure 1. Stickiness conceptual model

MAIN THRUST

E-commerce customer loyalty, or stickiness, results from goodwill created by the organization’s marketing efforts (Reichheld, 1996; Reichheld & Sasser, 1990), or Stickiness =f(Goodwill) (1) and Goodwill = f (Marketing Mix) (2)

By encouraging current and return visits, stickiness will influence the organizations’ volume. Marketing theory also suggests that the mix of price (including switching costs to consumers), product/service (including site characteristics), and promotion (including banner and other Web site ads), as well as other factors (including consumer characteristics), will influence this volume (Page et al., 1996; Storbacka et al., 1994). Hence,

Volume =f(Stickiness, Promotion, Product, Price, Other Factors) (3)

Such volume will determine revenue, cost, and thereby profit for the Web site.

According to standard accounting practice and economic theory, profit is defined as the excess of revenue

over cost, or

Profit = Revenue – Cost (4)

while revenue will equal volume multiplied by price, or

Revenue = Volume Price (5)

According to standard accounting and economic theory, an organization’s costs will have fixed and variable components, or

Total Cost = Fixed Cost + Variable Cost (6)

and variable cost will equal volume multiplied by unit cost, or

Variable Cost = Volume Unit Cost (7)

with volume as defined in equation (3).

These marketing-economic-accounting-theory-based relationships are illustrated in Figure 1. This figure and equations (1) – (7) provide a conceptual model that specifies the manner in which the stickiness investment can contribute to an e-business organization’s effectiveness by generating volume, revenue and profit. As such, the model identifies the information that must be collected to effectively evaluate investments in an e-commerce customer loyalty plan. These equations also provide a framework to objectively evaluate these plans and their impact on organizational operations and activities.

In practice, the model can be applied in a variety of ways. The general relationships can be used for strategy formulation at the macro-organizational level. In addition, the equations can be decomposed into detailed micro-level blocks with many variables and interrelationships. At this micro level, tactical policies to implement the macro strategies can be specified and evaluated.

EMPIRICAL TESTING

Much of the required model information is financial in nature. Such data are largely proprietary and therefore not readily available.

Summarized financial information is available from some Internet companies’ quarterly (10-Q) and annual reports and other public sources. In particular, data were obtained from the 10-Q and 10-K reports for 20 Internet companies over the period 1999-2000. This pooled cross-section, time series data provided values for the revenue and marketing mix variables found in equations (1) – (7). Customer characteristics were proxied through demographic variables, and data for these variables were obtained from U.S. Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States for the period 1999-2000. The quarterly and annual report and Census data provided 120 observations to operationalize the model embodied in equations (1) – (7).

Goodwill, as defined in the economic literature (repeat business based on happy customers), is also not available from the annual and quarterly reports. However, an accounting measure of goodwill, amortization of goodwill and other intangible assets is available from the reports. Although not strictly the same concept as marketing goodwill, the accounting measure is likely to be correlated with economic goodwill and is thereby used as a proxy for economic goodwill (Chauvin & Hirschey, 1994; Jennings et al., 1996; McCarthy & Schneider, 1995).

No other data were provided by the available sources on a consistent and reliable basis. These data limitations reduced the variable list that could be used to operationalize the stickiness model specified in equations (1) – (7) to the list summarized in Table 1. To test the theory, then, it was necessary to use a truncated form of Figure 1′s stickiness model.

Since, equations (4)-(7) in Figure 1′s stickiness model are identities, only equations (1)-(3) must be estimated statistically from the available data. Prior research has shown that marketing investments in one period can continue to affect volume in subsequent periods (Hanson, 2000). Marketers call this phenomenon the carryover, lagged, or holdover effect. Stickiness investments and the marketing mix can be expected to create such an effect from new customers who remain with the Web site for many subsequent periods. Because of the data limitations, this important lagged effect had to be measured quarterly, and the carryover had to be restricted to one period. From the relationships in Figure 1, it seems reasonable to assume that the holdover will be expressed through the goodwill variable. Namely, goodwill in the previous quarter is assumed to affect revenue in the current quarter.

Table 1. Variables with data

| VARIABLE | DEFINITION |

| Volume V | total sales volume of the Internet company |

| Goodwill GW | amortization of goodwill and other intangible assets |

| Promotion A | sales and marketing expenditures |

| Product Quality Q | product development costs, which include research and development and other product development costs |

| Average Income AI | average consumer income |

| Stickiness S | number of unique visitors at the firm’s Web site |

Table 2. Results of the SUR estimation

| Equation | MSE | R-Square | Adj. R-Square |

| Volume (equation 8) | 0.3894 | 0.7408 | 0.7299 |

| Stickiness (equation | 0.2190 | 0.1944 | 0.1862 |

| 9) | |||

| Goodwill (equation | 3.5312 | 0.1296 | 0.1208 |

| 10) |

Table 3. SUR-estimated log-linear result

| Variable | Volume (Vt) | Stickiness(St) | Goodwill (GWt) | |||

| Est. | Prob>|T| | Est. | Prob>|T| | Est. | Prob>|T| | |

| Constant | -5.09 | .8282 | 8.74 | <.0001 | 1.19 | .0037 |

| Stickiness | 0.58 | .0002 | ||||

| Promotion | 0.95 | <.0001 | ||||

| Income | 0.09 | .9885 | ||||

| Lagged Goodwill | 0.05 | .1739 | ||||

| Goodwill | 0.17 | <.0001 | ||||

| Product Quality | 0.77 | <.0001 | ||||

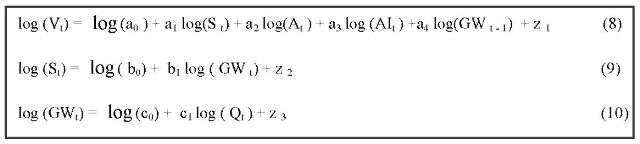

At time period t, the inputs may have joint, rather than independent, effects on volume. Moreover, elasticities (the percentage change in an output generated by a 1% change in an input) can provide useful information for policy making and analysis. To account for the nonlinearities, to facilitate the computation of elasticities, and to account for the carryover effect, equations (1) – (3) can be specified with the popular Cobb-Douglas production function, or in log-linear form in equations (8) – (10).

In equations (8) – (10), t denotes the considered time period (quarter), the a, b, c, and z labels denote parameters to be estimated, and the other variables are defined in Table 1. Price is excluded from the volume equation because data for the price variable are unavailable from the annual and quarterly reports.

Equations (8) – (10) below, form a simultaneous system of equations. Hence, simultaneous equation estimation techniques should be used to separate the effects of the marketing instruments and stickiness on volume. Otherwise, there will be a statistical identification problem.

There are several simultaneous estimation techniques that can be used to estimate the operational stickiness model (equations (8)-(10)). Using coefficients of determination, theoretical correctness of the estimated parameters, and forecasting errors as guidelines, the best results were generated by seemingly unrelated regressors (SUR). These results are summarized in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2 shows that the volume equation (8) has an R2 = 0.74 and thereby accounts for about 74% of the variation in this variable. More importantly, Table 3 shows that the estimated coefficient of the stickiness variable in equation (9) is significant at the a = .05 level, suggesting that volume is significantly influenced by the stickiness of the Web site.

Table 2 shows that the operational stickiness model accounts for a relatively small percentage of the variation in stickiness and goodwill. Nevertheless, Table 3 indicates that goodwill has positive and significant effects on the stickiness of the Web site, while marketing instruments, such as product quality, also create positive effects on goodwill.

In short, the operational stickiness model provides reasonable statistical results. These results validate the theory that stickiness is an investment that, along with the marketing mix, will influence organizational performance. The results also indicate that volume will have inelastic responses to stickiness and promotion investments. That is, a 1% increase in such investments will lead to a less than 1% increase in volume. There are similar inelastic responses of stickiness to goodwill and goodwill to product quality.

FUTURE TRENDS

The analysis also suggests future research directions. First, it is useful to determine whether there are significant carryover effects from goodwill. If significant carryover effects are discovered, research should examine how long the investment in stickiness would contribute to the firm’s short-term or long-term financial success. Second, research should evaluate what role competition plays in stickiness analysis. For example, additional research may examine how competitors’ stickiness investments impact the firm.

Empirical e-commerce evaluations, then, will require the collection, capture, and retrieval of pertinent and consistent operational financial and other data for evaluation purposes. Appropriate statistical methodologies will be needed to estimate the proffered model’s parameters from the collected data. Information systems will be required to focus the data, assist managers in the estimation process, and help such users to evaluate experimental customer loyalty plans. These tasks and activities offer new, and potentially very productive, areas for future research.

CONCLUSION

Figure 1′s stickiness model shows how to measure the impact of online stickiness on revenue and profit, and the model also shows how stickiness and goodwill are related. The operational model can demonstrate and forecast the long-term revenue, profit, and return on investment from a Web site’s products/services. In addition, the operational model: (a) provides a mechanism to evaluate Web redesign strategies, (b) helps Web managers evaluate market changes on custom loyalty plans, and (c) provides a framework to determine the “best” stickiness and other marketing policies.

In sum, in the e-commerce world, marketing still provides leadership in identifying consumer needs, the market to be served, and the strategy to be launched. Web managers must realize that desirable financial outcomes depend on their marketing effectiveness. With Figure 1′s conceptual stickiness model, Web managers and marketers have a tool to evaluate their investment decisions.

KEY TERMS

Customer Attraction: The ability to attract customers at the Web site.

Customer Loyalty: The ability to develop and maintain long-term relationships with customers by creating superior customer value and satisfaction.

Customer Loyalty Plan: A strategy for improving financial performance through activities that increase stickiness.

Customer Retention: The ability to retain customers and their allegiance to the Web site.

Goodwill: The amount of repeat business resulting from happy and loyal customers.

Stickiness: The ability of a Web site to create both customer attraction and customer retention for the purpose of maximizing revenue or profit.

Stickiness Model: A series of interdependent equations linking stickiness to an organization’s financial performance.