If you want to build a digital library, the first questions that need to be answered are: What form are the documents in? What structure do they have? How do you want them to look?

Documents, Topics, sections

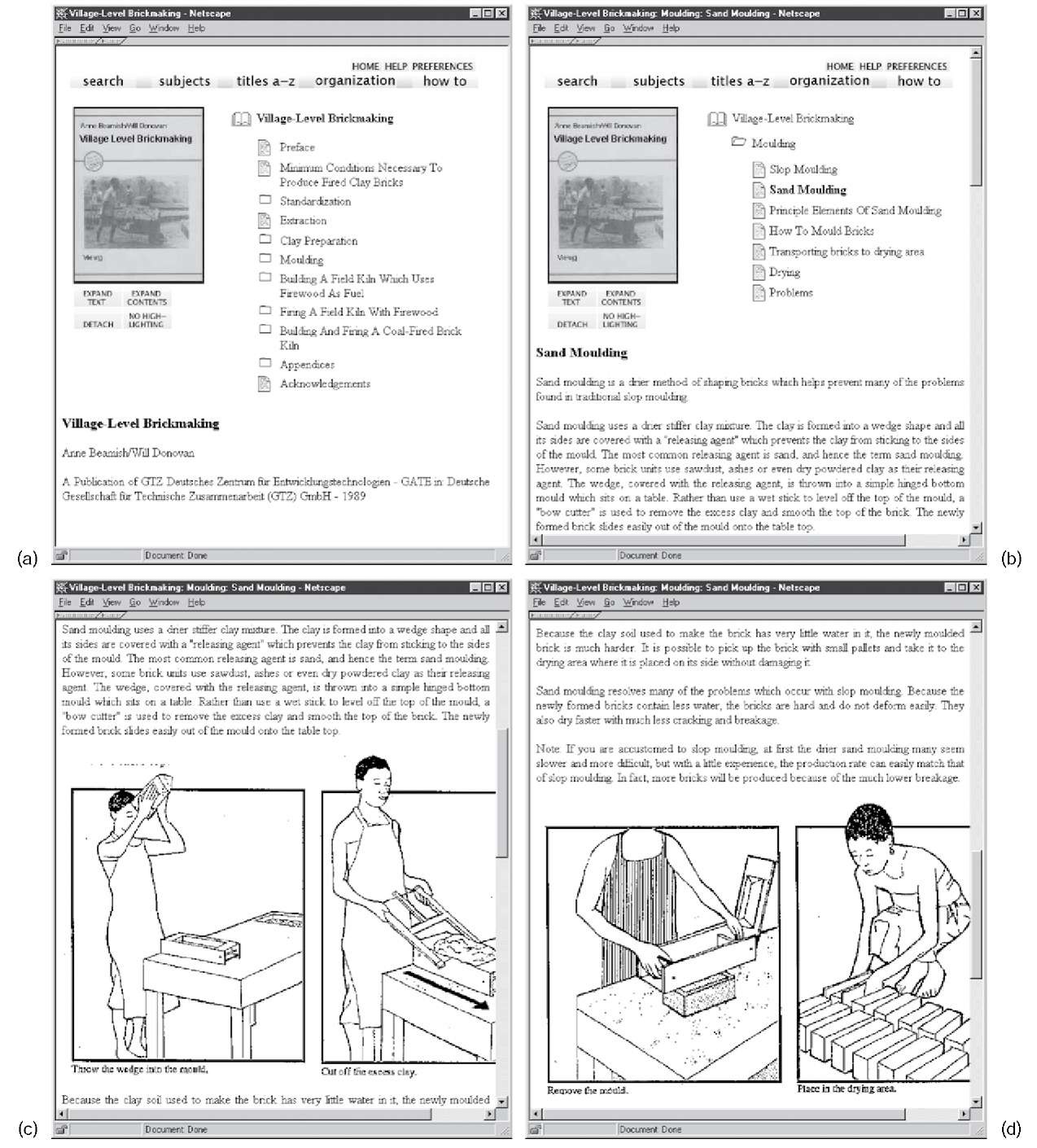

The book shown in Figure 3.1, Village-Level Brick making, is from the Humanity Development Library mentioned in topic 1. A picture of the front cover is displayed on the left, and the table of contents appears to its right. Below is the start of the main text, beginning with title, author.The books in this collection are generously illustrated. On the screen these images appear in-line, just as they did in the paper books from which the collection was derived. Figures 3.1c and d show some of the images, obtained by scrolling down from Figure 3.1b.

Books in this collection have front-cover images, which appear at the top of any page where the book, or part of it, is displayed. This picture gives a feeling of physical presence, a reminder of the context in which you are reading. The user interface may be a poor substitute for the look and feel of a physical book—the heft, the texture of the cover, the crinkling sound of pages turning, the smell of the binding, highlighting and marginal notes on the pages, dog-eared leaves, coffee stains, the pressed wildflower that your lover always used as a bookmark—but it’s a lot better than nothing.

Figure 3.1: Village-Level Brickmaking: (a) the book; (b) the topic on Moulding; (c, d) some of the pages.

The books in the Humanity Development Library are structured into topics and sections. The small folder icons in Figure 3.1a indicate topics—there are topics on Standardization, Clay Preparation, Moulding, and so on. The small text-page icons beside the Preface, Extraction, and Acknowledgements headings indicate leaves of the hierarchy: sections that contain text but no further subsection structure.

Clicking on Moulding in Figure 3.1a yields the page in Figure 3.1b, which shows the topic’s structure in the form of a table of contents. Here the user has opened the book to Sand moulding by clicking its text-page icon; the section heading is shown in bold and its text appears below. Other headings lead the reader to such topics as Slop moulding, How to mould bricks, and Drying. You can read the beginning of the Sand moulding section in Figure 3.1b: the scroll bar to the right of the screen indicates that more text follows. Figures 3.1c and d show the effect of scrolling further down the page.

The Expand Contents button in Figure 3.1 expands the table of contents into a full hierarchical structure. Similarly, the Expand Text button expands the text of the section being displayed. In Figure 3.1a it would yield the text of the entire topic, including all topics and subsections; in Figure 3.1b it would yield the complete text of the Moulding topic, including all subsections. This is convenient for printing the whole book or sections of it. Finally, the Detach button duplicates this window on the screen, so that you can retain its text while continuing to browse the library in the other window. This is useful for comparing multiple documents.

As noted in topic 1, the Humanity Development Library is a large compendium of practical material. It covers diverse areas of human development, from agricultural practice to foreign policy, from water and sanitation to society and culture, from education to manufacturing, from disaster mitigation to microenterprises. This material was carefully selected and put together by a collection editor who acquired the books, arranged for permission to include each one, organized a massive optical character recognition (OCR) operation to convert them into electronic form, set and monitored quality-control standards for the conversion, decided what form the digital library should take and what searching and browsing options should be provided, entered the metadata necessary to build these structures, and checked the integrity of the information and the look and feel of the final product. The care and attention put into the collection is reflected by its high quality. Nevertheless, it is not perfect: there are small OCR errors, and some of the 30,000 in-text figures (of which examples can be seen in Figures 3.1c and d) are inappropriately sized.

Unstructured text documents

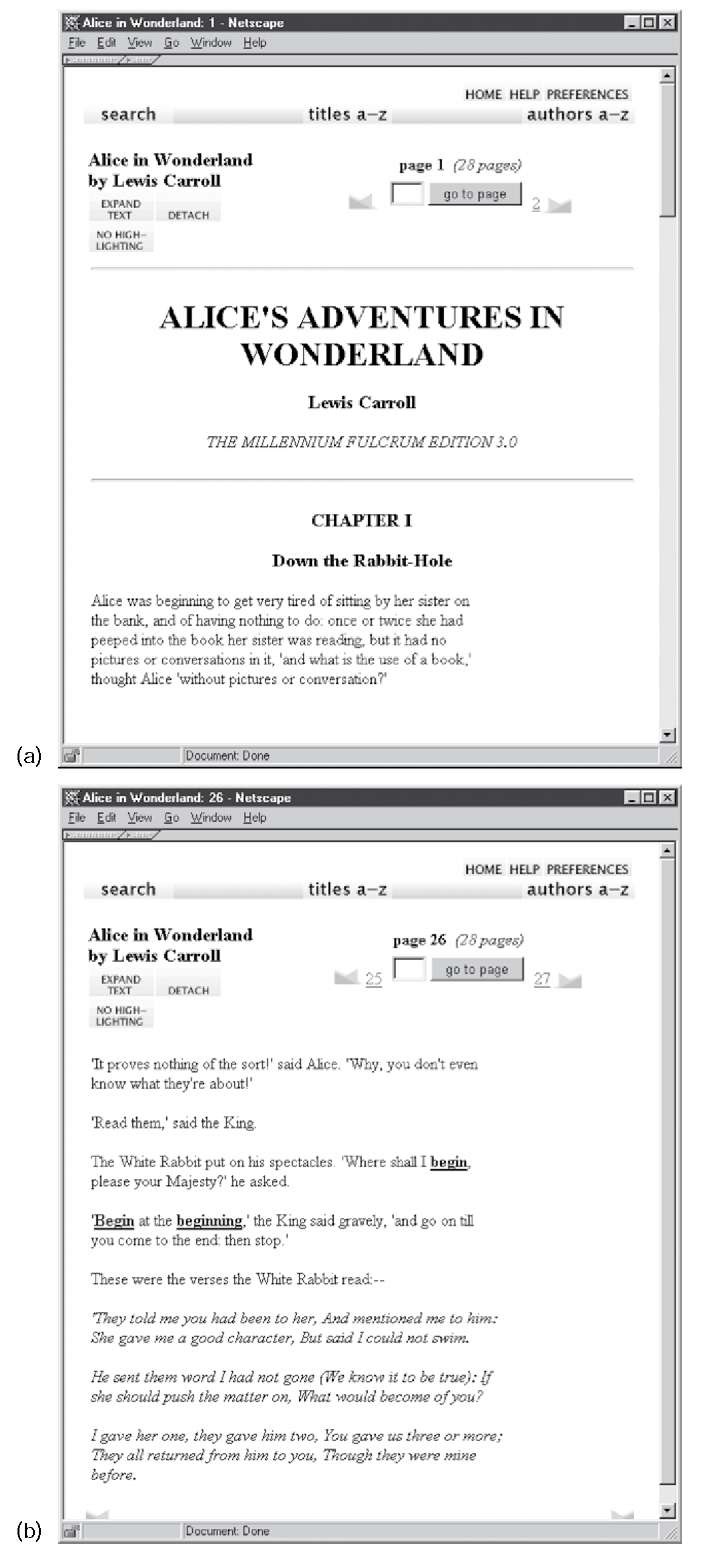

Figure 3.2 shows screen shots from a far plainer collection. The documents are not presented in a hierarchical way. There are no front-cover images. In place of Figure 3.1′s picture and table of con- tents, what Figure 3.2 shows is more prosaic: the title of the book and a page selector that lets you turn from one page to another.

Figure 3.2: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland: (a) the beginning; (b) finding a quotation

Browsing is less convenient because there is less structure to work with. Even the "pages" do not correspond to physical pages.The only reason for having pagination at all is to prevent the Web browser from downloading the entire book every time you look at it.

In fact, this topic does have topics—in Figure 3.2 you can see the beginning of topic 1, Down the rabbit-hole. However, this structure is not known to the digital library system: the book is treated as a long scroll of plain text. With some extra effort in setting up the collection, it would have been possible to identify the beginning of each topic, and its title, and incorporate this information to permit browsing topic by topic, as has been done in the Humanity Development Library. The cost depends on how similar the books in the collection are to one another and how regular the structure is. For any given book, or any given structure, it is easy to do; but in real life large collections usually exhibit considerable variation in format. As we mentioned before, the task of proofreading thousands of books is not to be undertaken lightly.

The books in this collection are stored as raw text, with the end of each line hard-coded, rather than, say, in HTML, which is used for Figure 3.1. (topic 4 gives details of these formats.) That is why the lines of text in Figure 3.2 are quite short: they always remain exactly the same length and do not expand to fill the browser window. Compared with the Humanity Development Library, this is a low-quality, unattractive collection. Removing end-of-line codes would be trivial, but a simple removal algorithm would destroy the format of tables of contents and displayed bullet points. It is surprisingly difficult to do such things reliably on large quantities of real text—reliably enough to avoid the chore of manual proofreading.

This is because the page was reached by a text search of the entire library contents (described in Section 3.4) to find a particular quotation. The system highlights search terms: there is a button at the top that turns highlighting off if it becomes annoying. In contrast, standard Web search engines do not highlight search terms in documents—of course, they do not serve up the target documents themselves but instead direct the user to the original source location.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland belongs to a collection called Project Gutenberg, whose goal is to encourage the creation and distribution of electronic text. Although the project was conceived in 1971, work on it did not begin in earnest until 1991, with the aim of producing 10,000 electronic texts within ten years. The first achievement was an electronic version of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, followed by the Bill of Rights and the Constitution. Then came the Bible and Shakespeare—unfortunately, however, the latter could not be released until much later because of copyright restrictions on the comments and notes in the particular edition that was entered. The collection was planned to double each year, with one book per month added in 1991, two in 1992, four in 1993, and so on, reaching the target of 10,000 by 2001. This schedule slipped slightly, but the target was passed in 2003.

A huge boost came from a development known as distributed proofreading, which provides a perfect example of the role of user contributions mentioned in Section 2.5. Optical character recognition (OCR) software is used to digitize volumes en masse. Then a global community of volunteers proofreads the result and corrects errors using a specially designed Web site. Upon logging in, registered volunteers are presented with a scanned page and the corresponding text in editable form, for correction. Once corrections have been made, a second volunteer verifies the work. Developed in 2000, this approach became an official part of Project Gutenberg two years later. The Project Gutenberg library now boasts over 26,000 digitized texts and continues to grow fast.

Project Gutenberg is a grassroots phenomenon. Text is input by volunteers, each of whom can enter a book a year or even just one book in a lifetime. The project does not direct the volunteers’ choice of material; instead, people are encouraged to choose books they like and to enter them in the manner in which they feel most comfortable. Central to the project’s philosophy is to represent books as plain text, with no formatting and no metadata other than title and author. Professional librarians look askance at amateur efforts like this, and indeed quality control is a problem. However, dating back two decades before the advent of the World Wide Web, the Gutenberg vision is remarkably far-sighted and gives an interesting perspective on the potential role of volunteer labor in placing society’s literary treasures in the public domain.

The collection illustrated in Figure 3.2 represents the opposite end of the spectrum to the Humanity Development Library. It took just a few hours to download the Project Gutenberg files and to create the collection, and a few hours of computer time to build it. Despite this tiny investment of effort, it is fully searchable—which makes it indispensable for finding obscure quotations—and includes author and title lists. If you want to know the first sentence of Moby Dick, or whether Hermann Melville wrote other popular works, or whether "Ishmael" appears as a central character in any other books, or the relative frequencies of the words he and her, his and hers in a large collection of popular English literature, this is where to come.

Page images

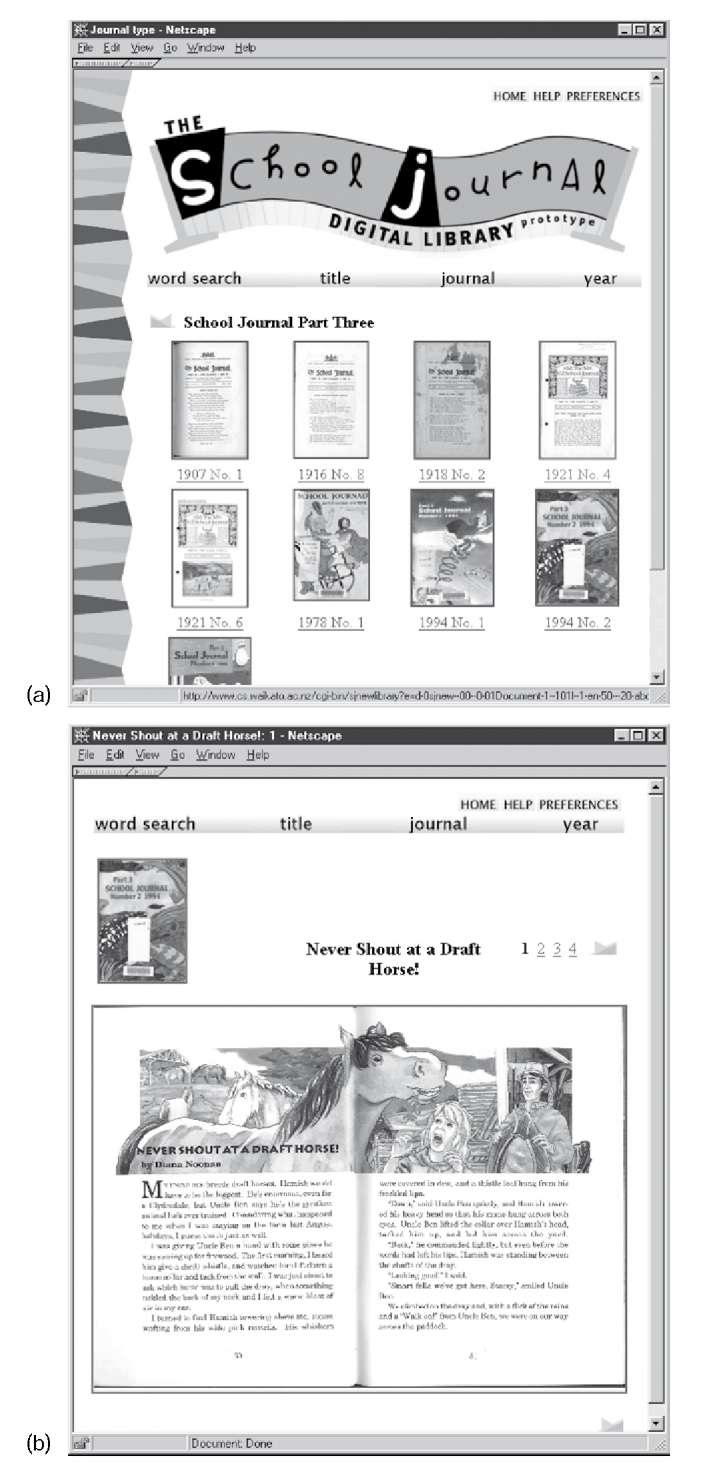

Figure 3.3 shows a historical collection of literature written for schoolchildren, the New Zealand School Journal, which is delivered to schools throughout New Zealand by the Ministry of Education. Dating from 1907—the first cover is the top left image in Figure 3.3—it is believed to be the longest-running serial publication for children in the world. Figure 3.3a shows the collection’s home page: you click on an image to get to that issue of the journal. Figure 3.3b shows a page of the children’s story "Never Shout at a Draft Horse," represented not as text but as a facsimile of the original printed version—a decision made by the collection’s designer. From a technical point of view, this decision makes a big difference: the textual content occupies only about 5 percent of the storage space required for a page image, greatly reducing the resources required to store the collection and the time needed to download each page. Of course, the picture of the horse would have to be represented as an image, just as the pictures in Figures 3.1c and d are, sacrificing some of the space gained.

A good reason for showing page images rather than extracted text is that the OCR process that identifies and recognizes the text content makes errors. When children are the target audience, it is important not to expose them to erroneous text. Of course, errors can be detected and corrected manually, as in the Humanity Development Library and the Gutenberg collection, but at a substantial cost well beyond the resources that could be mustered for this particular project.

Figure 3.3: School Journal Digital Library (Learning Media Limited, Wellington, New Zealand): (a) home page; (b) the story "Never Shout at a Draft Horse!" by Diana Noonan.

Text is indeed extracted from the New Zealand School Journal pages using OCR, and that text is used for searching, but readers never see it. The consequence of OCR errors is that some searches may not return all the pages they should. If a word on a particular page is misrecognized, a search for it will not return that page. Or, if a particular word is misinterpreted as a different one, a search for that word will return an extra page. However, neither of these errors was seen as a big problem— certainly not as serious as showing children corrupted text.

Figure 3.3b shows the journal cover at the top left and a page selector at the right that is more convenient to use for browsing around in the story than the numeric selector in Figure 3.2. The stories are short: ‘Never Shout at a Draft Horse" has only four pages.

Images with text

Figure 3.4 demonstrates a far larger collection of page images that also allows searching on extracted, OCR’d text, but in this case users are able to see the text if they so desire. This is the National Library of New Zealand’s Papers Past collection, which has 1.1 million pages of digitized national and regional newspaper and periodicals spanning the years 1839-1920.

A user interested in the suffragette movement has entered the query Kate Sheppard (Kate Sheppard was a prominent 19th-century campaigner who successfully campaigned to have New Zealand become the first country where women could vote). Figure 3.4a shows the beginning of one of the articles returned by the search, "To the Freewomen of New Zealand," from p. 46 of the Otago Witness (Issue 2066, 28 September 1893). Notice that (unlike in the School Journal collection) the search terms are highlighted in this image. During the OCR process, the precise location of each word in the source image is stored, along with coordinate information for each article. This allows search terms to be highlighted and individual articles to be clipped out of the newspaper pages.

A link at the top takes the reader to the text shown in Figure 3.4b. Some errors are apparent, most notably the word names—the last word shown in Figure 3.4a—has been rendered as niiniis. The decision to allow readers to see this text was a good one, for then they can see what they are searching. It is also a courageous decision because it exposes errors, and most digital libraries of newspapers conceal this information. In this case, the word names in Figure 3.4a is badly broken up: no wonder it was misrecognized.

From Figure 3.4c readers can view both a high-resolution image and a printable version. They can navigate page by page through the newspaper, and from one edition to the next. Figure 3.4d shows the contents of this edition of the Otago Witness, providing a useful overview. At the top, the user can obtain a printable version of the full edition (in the PDF, Portable Document Format, that is described in Section 4.5). The first column provides navigable links to each page; the second provides links to each article.

Figure 3.4: The National Library of New Zealand’s Papers Past: (a) viewing a newspaper; (b) text view;

Figure 3.4, cont’d: (c) the article in context; (d) contents of a newspaper issue

This is just a glimpse of what the Papers Past digital library has to offer. Such magnificent functionality does not come cheap. For example, a huge amount of metadata is involved. Normally, storage requirements for the source documents vastly outstrip those needed for the accompanying metadata. Here, however, this is reversed: for every gigabyte of text extracted by the OCR process, three times as much space is consumed by the coordinate information—metadata. In fact, the 1 MB of metadata required for a page exceeds the 0.75 MB required even for the scanned page image, let alone for the text extracted from it.

Realistic books

Section 1.2 describes how it took centuries for the written word to progress from papyrus scrolls to the book form that we use today. The book was a revolutionary development that changed the way people read written information; it is arguably one of the most important inventions in the history of thought. Consequently, it is perplexing that the scroll bar, reminiscent of long-obsolete technology, has dominated our computer interfaces for the past three decades.

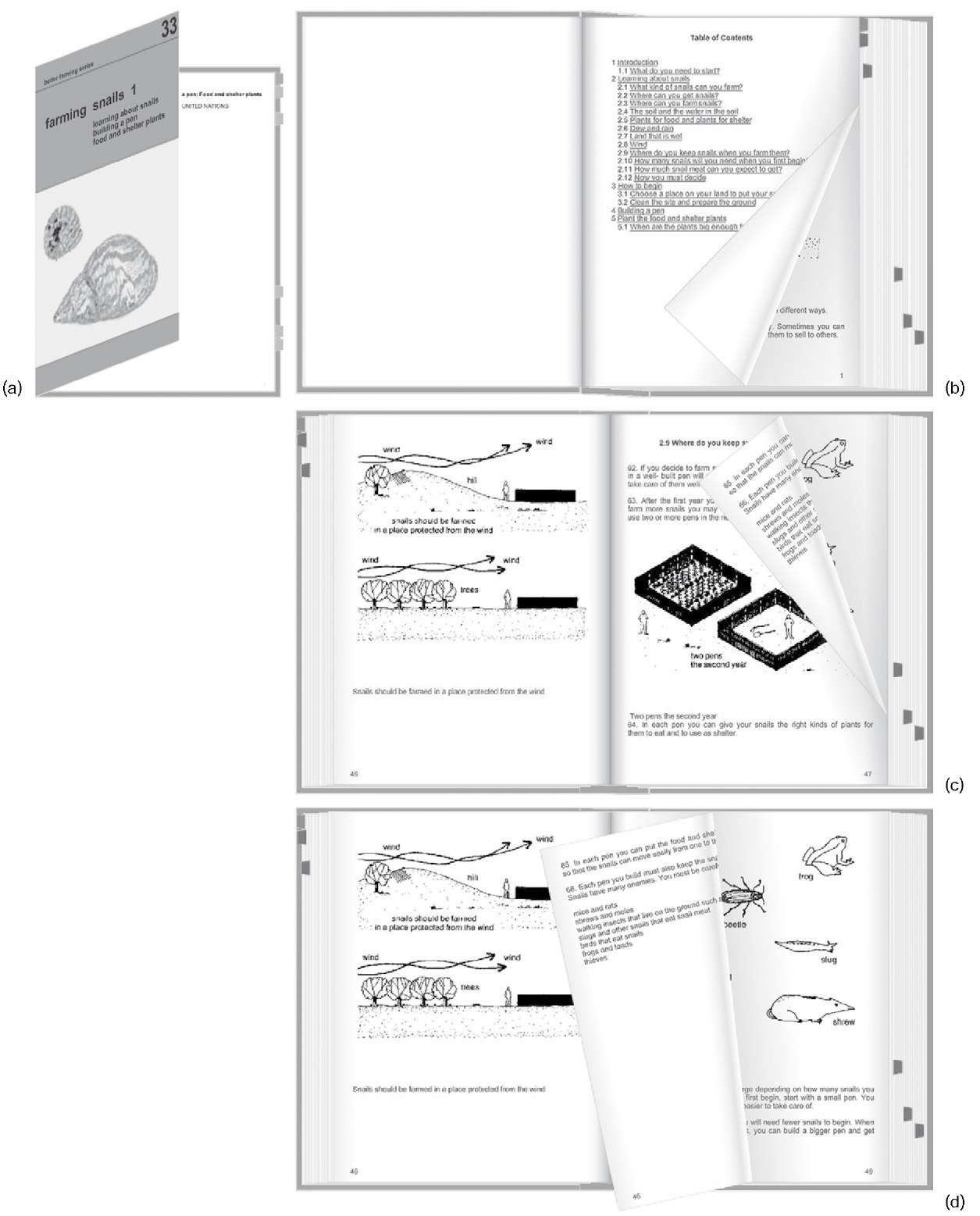

The book is coming back. Figure 3.5 shows an interface that much more closely resembles physical documents than the representations in earlier figures. Because it works in a standard Web browser, it can be widely deployed. Readers use a mouse to grasp the paper and sweep out the path of that point to turn the page. There is complete freedom to move the page within the constraints imposed by not moving it to a point that would tear physical paper, and the visual details follow instantly. Although the model does not look completely realistic in static pictures, it is effective in practice because it is dynamically reactive.

Readers grasp the page anywhere along the top, right, or bottom edge—usually, but not necessarily, at a corner—by pointing their mouse there and depressing and holding down the mouse button. As they move the mouse, the page follows. If they release the button, the page either floats back to its original position or floats down to the turned position. Readers who use a touch panel instead of a mouse gain an even better sense of control.

Realistic books typically have a cover (Figure 3.5a), title page, table of contents (Figure 3.5b), and the main text (Figures 3.5c and d). Sections begin on a new page and are split into pages. Contents entries are hyperlinked, so that clicking them opens the book to that topic. Colored tabs protruding from the page edges mark topics, sections, or pages containing illustrations (these things are switchable). The reader turns pages by using the mouse or simply by clicking to turn them automatically. When the book is open, the cover’s inside border is visible, and the reader can click this to close the book in either direction.

The presentation in Figure 3.5a was generated by the same digital library system used for Figure 3.1. Any book in the Humanity Development Library can be displayed in this way; the software converts it on the fly from the HTML representation.

Figure 3.5: Browsing through a realistic book: Farming Snails I: (a) opening the front cover; (b) contents; (c, d) turning some pages.

This serves to underscore the fact that digital libraries can change the entire look and feel of all documents in a collection at the touch of a button—or, as in this case, a single menu selection on a Preferences page.