Is a digital library an institution or a piece of technology? The term digital library, like the word library, means different things to different people. Many people think of libraries as bricks and mortar, a quiet place where books are kept. To professional librarians, they are institutions that arrange for the preservation, collection, and organization of material, as well as for access to it. And a library’s material is not just books: there are libraries of art, film, sound recordings, botanical specimens, and cultural objects. To researchers, libraries are networks that provide ready access to the world’s recorded knowledge, wherever it is held. Today’s university students of science and technology, sadly, increasingly think of libraries as the World Wide Web—that is, they misguidedly regard the Web as the ultimate library.

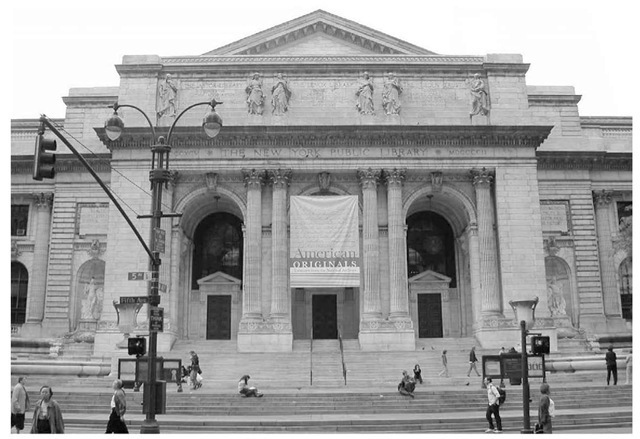

A digital library is not simply a "digitized library." We hope that you are reading How to Build a Digital Library because you are thinking of building one. However, we do not imagine that you are the director of the New York Public Library, contemplating replacing that magnificent edifice with a computer (Figure 1.3). Nor do we want you to think, even for a moment, of burning your books at home and sitting by the fireside on winter evenings absorbed in a flat-panel computer display. (Some say that, had books been invented after computers were, they would have been hailed as a great advance.) Rather, we hope that you are inspired by a vision, perhaps something like the examples we began with, of achieving new human goals by changing the way that information is used in the world. Digital libraries are about new ways of dealing with knowledge—preserving, collecting, organizing, propagating, and accessing it—not about deconstructing existing institutions and putting them in an electronic box.

In this topic, a digital library is defined as a focused collection of digital objects, including text, video, and audio, along with methods for access and retrieval, and for selection, organization, and maintenance of the collection.

This broad interpretation of "digital objects" (not just text) is reflected in the examples above. Beyond audio and video, we want to include 3D objects, simulations, dynamic visualizations, and virtual reality. The second and third parts of the definition of a digital library deliberately accord equal weight to user (access and retrieval) and librarian (selection, organization, and maintenance). The librarian’s functions are often overlooked by digital library proponents, who generally have a background in technology and approach their work from this perspective rather than from the viewpoint of library or information science.

But selection, organization, and maintenance are central to the notion of a library. If data is characterized as recorded facts, then information is the set of patterns, or expectations, that underlie the data.

Figure 1.3: the New York public Library

You could go on to define knowledge as the accumulation of your set of expectations, and wisdom as the value attached to knowledge. Not all information is created equal, and wisdom is what librarians add to the library by making decisions about what to include in a collection—difficult decisions—and by following up with appropriate ways of organizing and maintaining the information. Indeed, it is exactly these features that distinguish digital libraries from the anarchic mess that we call the World Wide Web.

Digital libraries do tend to blur what has traditionally been a sharp distinction between user and librarian. (The collections in the examples above were not, in the main, created by professional librarians.) Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind the distinction between the two roles. Digital library software supports users as they search and browse the collection; equally, it supports librarians as they strive to provide appropriate organizational structures and to maintain them effectively.

Digital libraries are libraries without walls. But they do need boundaries. The very notion of a collection implies a boundary: the fact that some things are in the collection means that others must lie outside it. And collections need a kind of presence, a conceptual integrity, that gives them cohesion and identity: that is where the wisdom comes in. Every collection should have a well-articulated purpose, which states the objectives it is intended to achieve, and a set of principles, which are the directives that will guide decisions on what should be included and—equally important—what should be excluded. These decisions are difficult.

Digital collections often present an appearance that is opaque: a screen (typically, a Web page) with no indication of what, or how much, lies beyond. Is it a carefully selected treasure or a morass of worthless ephemera? Are there half a dozen documents or many millions? At least physical libraries occupy physical space, present a physical appearance, and exhibit tangible physical organization. When standing on the threshold of a large bricks-and-mortar library, you gain a sense of presence and permanence that reflects the care taken in building and maintaining the collection inside. No one could confuse it with a dung heap! Yet in the virtual world the difference is not so palpable.

We draw a clear distinction between a digital library and the World Wide Web: the Web lacks the essential features of selection and organization. We also want to distinguish a digital library from a Web site—even one that offers a focused collection of well-organized material. Existing digital libraries invariably manifest themselves in this way. But a Web site that provides a wealth of digital objects, along with appropriate methods of access and retrieval, should not necessarily be considered a "library." Libraries are storehouses to which new material can easily be added. Many well-organized Web sites are created manually through hand-crafted hypertext linkage structures. But just as adding new acquisitions to a physical library does not involve delving into the books and rewriting parts of them, it should be possible for new material to become a first-class member of a digital library without any need for manual updating of the structures used for access and retrieval.

What establishes a new acquisition in tangible format in the collection structure of a physical library is partly where it is placed on the shelves, but more important is the information about it that is included in the library catalog. In digital libraries, we call the equivalent "cataloging" information metadata (data about data) and it figures prominently in the digital libraries described in this topic.