Abstract

Under the state corporate chartering system in the U.S., managers may seek shareholder approval to reincorporate the firm in a new state, regardless of the firm’s physical location, whenever they perceive that the corporate legal environment in the new state is better for the firm. Legal scholars continue to debate the merits of this system, with some arguing that it promotes contractual efficiency and others arguing that it often results in managerial entrenchment. We discuss the contrasting viewpoints on rein-corporations and then summarize extant empirical evidence on why firms reincorporate, when they re-incorporate, and where they reincorporate to. We conclude by discussing how the motives managers offer for reincorporations, and the actions they take upon reincorporating, influence how stock prices react to reincorporation decisions.

Introduction

Modern corporations have been described as a ”nexus of contractual relationships” that unites the providers and users of capital in a manner that is superior to alternative organizational forms. While agency costs are an inevitable consequence of the separation of ownership and control that characterizes corporations, the existence of clearly specified contractual relationships serves to minimize those costs. As Jensen and Meckling (1976, p. 357) noted:

The publicly held business corporation is an awesome social invention. Millions of individuals voluntarily entrust billions of dollars, francs, pesos, etc., of personal wealth to the care of managers on the basis of a complex set of contracting relationships which delineate the rights of the parties involved. The growth in the use of the corporate form as well as the growth in market value of established corporations suggests that, at least up to the present, creditors and investors have by and large not been disappointed with the results, despite the agency costs inherent in the corporate form.

Agency costs are as real as any other costs. The level of agency costs depends among other things on statutory and common law and human ingenuity in devising contracts. Both the law and the sophistication of contracts relevant to the modern corporation are the products of a historical process in which there were strong incentives for individuals to minimize agency costs. Moreover, there were alternative organizational forms available, and opportunities to invent new ones. Whatever its shortcomings, the corporation has thus far survived the market test against potential alternatives.

Under the state corporate chartering system that prevails in the U.S., corporate managers can affect the contractual relationships that govern their organizations through the choice of a firm’s state of incorporation. Each state has its own distinctive corporate laws and established court precedents that apply to firms incorporated in the state. Thus, corporations effectively have a menu of choices for the firm’s legal domicile, from which they may select the one they believe is best for their firm and/or themselves. The choice is not constrained by the physical location either of the firm’s corporate headquarters or its operations. A firm whose headquarters is in Texas may choose Illinois to be its legal domicile, and vice versa. Corporations pay fees to their chartering states, and these fees vary significantly across states, ranging up to $150,000 annually for large companies incorporated in Delaware. State laws of course evolve over time, and managers may change their firm’s legal domicile – subject to shareholder approval – if they decide the rules in a new jurisdiction would be better suited to the firm’s changing circumstances. This is the process referred to as reincorporation, and it is our topic of discussion here.

Competition Among States for Corporate Charters

There has been a long-running debate among legal and financial scholars regarding the pros and cons of competition among states for corporate charters. Generally speaking, the proponents of competition claim that it gives rise to a wide variety of contractual relationships across states, which allows the firm to choose the legal domicile that serves to minimize its organizational costs and thereby maximize its value. This ”Contractual Efficiency” viewpoint, put forth by Dodd and Leftwich (1980), Easterbrook and Fischel (1983), Baysinger and Butler (1985), and Romano (1985), implies the existence of a determinate relationship between a company’s attributes and its choice of legal residency. Such attributes may include: (1) the nature of the firm’s operations, (2) its ownership structure, and (3) its size. The hypothesis following from this viewpoint is that firms that decide to reincorporate do so when the firm’s characteristics are such that a change in legal jurisdiction increases shareholder wealth by lowering the collection of legal, transactional, and capital-market-related costs it incurs.

Other scholars, however, argue that agency conflicts play a significant role in the decision to reincorporate, and that these conflicts are exacerbated by the competition among states for the revenues generated by corporate charters and the economic side effects that may accompany chartering (e.g. fees earned in the state for legal services). This position, first enunciated by Cary (1974), is referred to as the ”Race-to-the-Bottom” phenomenon in the market for corporate charters. The crux of the Race-to-the-Bottom argument is that states that wish to compete for corporate chartering revenues will have to do so along dimensions that appeal to corporate management.

Hence, states will allegedly distinguish themselves by tailoring their corporate laws to serve the self-interest of managers at the expense of corporate shareholders. This process could involve creating a variety of legal provisions that would enable management to increase its control of the corporation, and thus to minimize the threats posed by outside sources. Examples of the latter would include shareholder groups seeking to influence company policies, the threat of holding managers personally liable for ill-advised corporate decisions, and – perhaps most important of all -the threat of displacement by an alternative management team. These threats, considered by many to be necessary elements in an effective system of corporate governance, can impose substantial personal costs on senior managers. That may cause managers to act in ways consistent with protecting their own interests – through job preservation and corporate risk reduction – rather than serving the interests of shareholders. If so, competition in the market for corporate charters will diminish shareholder wealth as states adopt laws that place restrictions on the disciplinary force of the market for corporate control (see Bebchuk, 1992; Bebchuk and Ferrell, 1999; Bebchuk and Cohen, 2003).

Here, we examine the research done on reincorporation and discuss the support that exists for the contrasting views of both the Contractual Efficiency and Race-to-the-Bottom proponents. In the process, we shall highlight the various factors that appear to play an influential role in the corporate chartering decision.

Why, When, and Where to Reincorporate

To begin to understand reincorporation decisions, it is useful to review the theory that relates a firm’s choice of chartering jurisdiction to the firm’s attributes, the evidence as to what managers say when they propose reincorporations to their shareholders, and what managers actually do when they reincorporate their firms.

Central to the Contractual Efficiency view of competition in the market for corporate charters is the notion that the optimal chartering jurisdiction is a function of the firm’s attributes. Reincor-poration decisions therefore should be driven by changes in a firm’s attributes that make the new state of incorporation a more cost-effective legal jurisdiction. Baysinger and Butler (1985) and Romano (1985) provide perhaps the most convincing arguments for this view.

Baysinger and Butler theorize that the choice of a strict vs. a liberal incorporation jurisdiction depends on the nature of a firm’s ownership structure. The contention is that states with strict corporate laws (i.e. those that provide strong protections for shareholder rights) are better suited for firms with concentrated share ownership, whereas liberal jurisdictions promote efficiency when ownership is widely dispersed. According to this theory, holders of large blocks of common shares will prefer the pro-shareholder laws of strict states, since these give shareholders the explicit legal remedies needed to make themselves heard by management and allow them actively to influence corporate affairs. Thus, firms chartered in strict states are likely to remain there until owner ship concentration decreases to the point that legal controls may be replaced by market-based governance mechanisms.

Baysinger and Butler test their hypothesis by comparing several measures of ownership concentration in a matched sample of 302 manufacturing firms, half of whom were incorporated in several strict states (California, Illinois, New York, and Texas) while the other half had reincorporated out of these states. In support of their hypothesis, Baysinger and Butler found that the firms that stayed in the strict jurisdictions exhibited significantly higher proportions of voting stock held by major blockholders than was true of the matched firms who elected to reincorporate elsewhere. Importantly, there were no differences between the two groups in financial performance that could explain why some left and others did not. Collectively, the results were interpreted as evidence that the corporate chartering decision is affected by ownership structure rather than by firm performance.

Romano (1985) arrived at a similar conclusion from what she refers to as a ”transaction explanation” for reincorporation. Romano suggests that firms change their state of incorporation ”at the same time they undertake, or anticipate engaging in, discrete transactions involving changes in firm operation and/or organization” (p. 226). In this view, firms alter their legal domiciles at key times to destination states where the laws allow new corporate policies or activities to be pursued in a more cost-efficient manner. Romano suggests that, due to the expertise of Delaware’s judicial system and its well-established body of corporate law, the state is the most favored destination when companies anticipate legal impediments in their existing jurisdictions. As evidence, she cites the high frequency of reincorporations to Delaware coinciding with specific corporate events such as initial public offerings (IPOs), mergers and acquisitions, and the adoption of antitakeover measures.

In their research on reincorporations, Heron and Lewellen (1998) also discovered that a substantial portion (45 percent) of the firms that reincorporated in the U.S. between 1980 and 1992 did so immediately prior to their IPOs. Clearly, the process of becoming a public corporation represents a substantial transition in several respects: ownership structure, disclosure requirements, and exposure to the market for corporate control. Accordingly, the easiest time to implement a change in the firm’s corporate governance structure to parallel the upcoming change in its ownership structure would logically be just before the company becomes a public corporation, while control is still in the hands of management and other original investors. Other recent studies also report that the majority of firms in their samples who undertook IPOs reincorporated in Delaware in advance of their stock offerings (Daines and Klausner, 2001; Field and Karpoff, 2002).

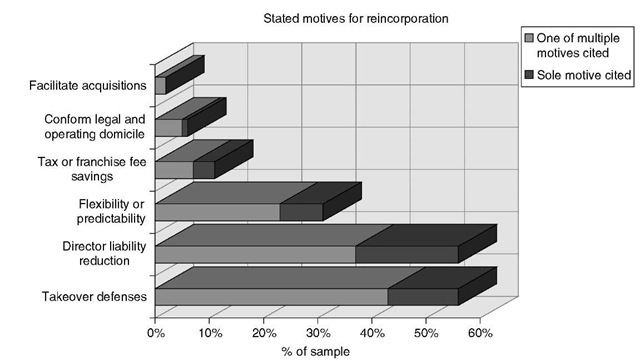

Perhaps the best insights into why managers choose to reincorporate their firms come from the proxy statements of publicly traded companies, when the motivations for reincorporation are reported to shareholders. In the process of the reincorporations of U.S. public companies that occurred during the period from 1980 through 1992, six major rationales were proclaimed by management (Heron and Lewellen, 1998): (1) takeover defenses; (2) director liability reduction; (3) improved flexibility and predictability of corporate laws; (4) tax and/or franchise fee savings; (5) conforming legal and operating domicile; and (6) facilitating future acquisitions.

A tabulation of the relative frequencies is provided in Figure 18.1. As is evident, the two dominant motives offered by management were to create takeover defenses and to reduce directors’ legal liability for their decisions. In addition, managers often cited multiple reasons for reincorporation. The mean number of stated motives was 1.6 and the median was 2. In instances where multiple motives were offered, each is counted once in the compilation in Figure 18.1.

What Management Says

It is instructive to consider the stated reincorporation motives in further detail and look at examples of the statements by management that are contained in various proposals, especially those involving the erection of takeover defenses and the reduction of director liability. These, of course, represent provisions that may not be in the best interests of stockholders, as a number of researchers have argued. The other motives listed are both less controversial and more neutral in their likely impact on stockholders, and can be viewed as consistent with Contractual Efficiency arguments for reincorporations. Indeed, reincor-porations undertaken for these reasons appear not to give rise to material changes in firms’ stock prices (Heron and Lewellen, 1998).

Figure 18.1. Stated motives for reincorporation

Reincorporations that Strengthen Takeover Defenses

Proponents of the Race-to-the-Bottom theory contend that the competition for corporate chartering may be detrimental if states compete by crafting laws that provide managers with excessive protection from the market for corporate control – i.e. from pressures from current owners and possible acquirers to perform their managerial duties so as to maximize shareholder wealth. Although takeover defenses might benefit shareholders if they allow management to negotiate for higher takeover premiums, they harm shareholders if their effect is to entrench poorly performing incumbent managers.

The following excerpts from the proxy statement of Unocal in 1983 provides an example of a proposal to reincorporate for antitakeover reasons:

In addition, incorporation of the proposed holding company under the laws of Delaware will provide an opportunity for inclusion in its certificate of incorporation provisions to discourage efforts to acquire control of Unocal in transactions not approved by its Board of Directors, and for the elimination of shareholder’s preemptive rights and the elimination of cumulative voting in the election of directors.

The proposed changes do not result from any present knowledge on the part of the Board of Directors of any proposed tender offer or other attempt to change the control of the Company, and no tender offer or other type of shift of control is presently pending or has occurred within the past two years.

Management believes that attempts to acquire control of corporations such as the Company without approval by the Board may be unfair and/or disadvantageous to the corporation and its shareholders. In management’s opinion, disadvantages may include the following:

a nonnegotiated takeover bid may be timed to take advantage of temporarily depressed stock prices;

a nonnegotiated takeover bid may be designed to foreclose or minimize the possibility of more favorable competing bids;

recent nonnegotiated takeover bids have often involved so-called “two-tier” pricing, in which cash is offered for a controlling interest in a company and the remaining shares are acquired in exchange for securities of lesser value. Management believes that “two-tier” pricing tends to stampede shareholders into making hasty decisions and can be seriously unfair to those shareholders whose shares are not purchased in the first stage of the acquisition; nonnegotiated takeover bids are most frequently fully taxable to shareholders of the acquired corporation.

By contrast, in a transaction subject to approval of the Board of Directors, the Board can and should take account of the underlying and long-term value of assets, the possibilities for alternative transactions on more favorable terms, possible advantages from a tax-free reorganization, anticipated favorable developments in the Company’s business not yet reflected in stock prices, and equality of treatment for all shareholders.

The reincorporation of Unocal into Delaware allowed the firm’s management to add several antitakeover provisions to Unocal’s corporate charter that were not available under the corporate laws of California, where Unocal was previously incorporated. These provisions included the establishment of a Board of Directors whose terms were staggered (only one-third of the Board elected each year), the elimination of cumulative voting (whereby investors could concentrate their votes on a small number of Directors rather than spread them over the entire slate up for election), and the requirement of a ”supermajority” shareholder vote to approve any reorganizations or mergers not approved by at least 75 percent of the Directors then in office. Two years after its move to Delaware, Unocal was the beneficiary of a court ruling in the Unocal vs. Mesa case [493 A.2d 946 (Del. 1985)], in which the Delaware Court upheld Unocal’s discriminatory stock repurchase plan as a legitimate response to Mesa Petroleum’s hostile takeover attempt.

The Unocal case is fairly representative of the broader set of reincorporations that erected takeover defenses. Most included antitakeover charter amendments that were either part of the reincor-poration proposal or were made possible by the move to a more liberal jurisdiction and put to a shareholder vote simultaneously with the plan of reincorporation. In fact, 78 percent of the firms that reincorporated between 1980 and 1992 implemented changes in their corporate charters or other measures that were takeover deterrents (Heron and Lewellen, 1998). These included eliminating cumulative voting, initiating staggered Board terms, adopting supermajority voting provisions for mergers, and establishing so-called ”poison pill” plans (which allowed the firm to issue new shares to existing stockholders in order to dilute the voting rights of an outsider who was accumulating company stock as part of a takeover attempt).

Additionally, Unocal reincorporated from a strict state known for promoting shareholder rights (California) to a more liberal state (Delaware) whose laws were more friendly to management. In fact, over half of the firms in the sample studied by Heron and Lewellen (1998), that cited antitakeover motives for their reincorporations, migrated from California, and 93 percent migrated to Delaware. A recent study by Bebchuk and Cohen (2003) that investigates how companies choose their state of incorporation reports that strict shareholder-right states that have weak anti-takeover statutes continue to do poorly in attracting firms to charter in their jurisdictions.

Evidence on how stock prices react to reincorporations conducted for antitakeover reasons suggests that investors perceive them to have a value-reducing management entrenchment effect. Heron and Lewellen (1998) report statistically significant (at the 95 percent confidence level) abnormal stock returns of —1.69 percent on and around the dates of the announcement and approval of reincorpora-tions when management cites only antitakeover motives. In the case of firms that actually gained additional takeover protection in their reincor-porations (either by erecting specific new takeover defenses or by adopting coverage under the anti-takeover laws of the new state of incorporation), the abnormal stock returns averaged a statistically significant —1.62 percent. For firms whose new takeover protection included poison pill provisions, the average abnormal returns were fully — 3.03 percent and only one-sixth were positive (both figures statistically significant). Taken together with similar findings in other studies, the empirical evidence therefore supports a conclusion that ”defensive” reincorporations diminish shareholder wealth.

Reincorporations that Reduce Director Liability

The level of scrutiny placed on directors and officers of public corporations was greatly intensified as a result of the Delaware Supreme Court’s ruling in the 1985 Smith vs. Van Gorkom case [488 A.2d 858 (Del. 1985)]. Prior to that case, the Delaware Court had demonstrated its unwillingness to use the benefit of hindsight to question decisions made by corporate directors that turned out after the fact to have been unwise for shareholders. The court provided officers and directors with liability protection under the ”business judgment” rule, as long as it could be shown that they had acted in good faith and had not violated their fiduciary duties to shareholders. However, in Smith vs. Van Gorkom, the Court held that the directors of Trans-Union Corporation breached their duty of care by approving a merger agreement without sufficient deliberation. This unexpected ruling had an immediate impact since it indicated that the Delaware Court would entertain the possibility of monetary damages against directors in situations where such damages were previously not thought to be applicable. The ruling contributed to a 34 percent increase in shareholder lawsuits in 1985 and an immediate escalation in liability insurance premiums for officers and directors (Wyatt, 1988).

In response, in June of 1986, Delaware amended its corporate law to allow firms to enter into indemnification agreements with, and establish provisions to limit the personal liability of, their officers and directors. Numerous corporations rapidly took advantage of these provisions by reincorporating into Delaware. Although 32 other states had established similar statutes by 1988 (Pamepinto, 1988), Delaware’s quick action enabled it to capture 98 percent of the reincorporations, which were cited by management as being undertaken to reduce directors’ liability, with more than half the reincorporating firms leaving California.

The 1987 proxy statement of Optical Coatings Laboratories is a good illustration of a proposal either to change its corporate charter in California or to reincorporate – to Delaware – for liability reasons, and documents the seriousness of the impact of liability insurance concerns on liability insurance premiums:

During 1986, the Company’s annual premium for its directors’ and officers’ liability insurance was increased from $17,500 to $250,000 while the coverage was reduced from $50,000,000 to $5,000,000 in spite of the Company’s impeccable record of never having had a claim. This is a result of the so-called directors’ and officers’ liability insurance crisis which has caused many corporations to lose coverage altogether and forced many directors to resign rather than risk financial ruin as a result of their good faith actions taken on behalf of their corporations.

This year at OCLI, we intend to do something about this problem. You will see included in the proxy materials a proposal to amend the Company’s Articles of Incorporation, if California enacts the necessary legislation, to provide the Company’s officers and directors with significantly greater protection from personal liability for their good faith actions on behalf of the Company. If California does not enact the necessary legislation by the date of the annual meeting, or any adjournment, a different proposal would provide for the Company to change its legal domicile to the State of Delaware, where the corporation law was recently amended to provide for such protection.

Although it was a Delaware Court decision that prompted the crisis in the director and officer liability insurance market, Delaware’s quick action in remedying the situation by modifying its corporate laws reflects the general tendency for Delaware to be attentive to the changing needs of corporations. Romano (1985) contends that, because Delaware relies heavily upon corporate charter revenues, it has obligated itself to be an early mover in modifying its corporate laws to fit evolving business needs. It is clear that this tendency has proven beneficial in enhancing the efficiency of contracting for firms incorporating in Delaware.

In contrast to the reaction to the adoption of antitakeover measures, investors have responded positively to reincorporations that were undertaken to gain improved director liability protection. Observed abnormal stock returns averaging approximately +2.25 percent (again, at the 95 percent confidence level) are reported by Heron and Lewellen (1998). In a supplemental analysis, changes in the proportions of outside directors on the Boards of firms that reincorporated for director liability reasons were monitored for two years subsequent to the reincorporations, as a test of the claim that weak liability protection would make it more difficult for firms to attract outsiders to their Boards. The finding was that firms that achieved director liability reduction via reincorpor-ation did in fact increase their outside director proportions by statistically significant extents, whereas there was no such change for firms that reincorporated for other reasons.

Other Motives for Reincorporations

Reincorporations conducted solely to gain access to more flexible and predictable corporate laws, to save on taxes, to reconcile the firm’s physical and legal domicile, and to facilitate acquisitions fall into the Contractual Efficiency category. Researchers have been unable to detect abnormal stock returns on the part of firms that have re-incorporated for these reasons. The bulk of the reincorporations where managers cite the flexibility and predictability of the corporate laws of the destination state as motivation have been into Delaware. Romano (1985) argues that Delaware’s responsive corporate code and its well-established set of court decisions have allowed the state to achieve a dominant position in the corporate chartering market. This argument would be consistent with the evidence that a substantial fraction of companies that reincorporate to Delaware do so just prior to an IPO of their stock. Indeed, Delaware has regularly chartered the lion’s share of out-of-state corporations undergoing an IPO: 71 percent of firms that went public before 1991, 84 percent that went public between 1991 and 1995, and 87 percent of those that have gone public from 1996 (Bebchuk and Cohen, 2002).

The language in the 1984 proxy statement of Computercraft provides an example of a typical proposal by management to reincorporate in order to have the firm take advantage of a more flexible corporate code:

The Board of Directors believes that the best interests of the Company and its shareholders will be served by changing its place of incorporation from the State of Texas to the State of Delaware. The Company was incorporated in the State of Texas in November 1977 because the laws of that state were deemed to be adequate for the conduct of its business. The Board of Directors believes that there is needed a greater flexibility in conducting the affairs of the Company since it became a publicly owned company in 1983.

The General Corporation Law of the State of Delaware affords a flexible and modern basis for a corporation action, and because a large number of corporations are incorporated in that state, there is a substantial body of case law, decided by a judiciary of corporate specialists, interpreting and applying the Delaware statutes. For the foregoing reasons, the Board of Directors believes that the activities of the Company can be carried on to better advantage if the Company is able to operate under the favorable corporate climate offered by the laws of the State of Delaware.

The majority of reincorporations which are done to realize tax savings or to reconcile the firm’s legal domicile with its headquarters involve reincorporations out of Delaware – not surprisingly, since Delaware is not only a very small state with few headquartered firms but also has annual chartering fees which are among the nation’s highest. The following excerpt from the 1989 proxy statement of the Longview Fibre Company illustrates the rationale for such a reincorporation:

Through the Change in Domicile, the Company intends to further its identification with the state in which the Company’s business originated, its principal business is conducted, and over 64% of its employees are located. Since the Company’s incorporation in the State of Delaware in 1926, the laws of the State of Washington have developed into a system of comprehensive and flexible corporate laws that are currently more responsive to the needs of businesses in the state.

After considering the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed Change in Domicile, the Board of Directors concluded that the benefits of moving to Washington outweighed the benefits and detriments of remaining in Delaware, including the continuing expense of Delaware’s annual franchise tax (the Company paid $56,000 in franchise taxes in fiscal year 1988, whereas the “annual renewal fee” for all Washington corporations is $50.00). In light of these facts, the Board of Directors believes it is in the best interests of the Company and its stockholders to change its domicile from Delaware to Washington.

Note in particular the issue raised about the annual franchise tax. Revenues from that source currently account for approximately $400 million of Delaware’s state budget (Bebchuk and Cohen, 2002).

Summary and Conclusions

Distinctive among major industrialized countries, incorporation in the U.S. is a state rather than a federal process. Hence, there are a wide variety of legal domiciles that an American firm can choose from, and the corporation laws of those domiciles vary widely as well – in areas such as the ability of shareholders to hold a firm’s managers accountable for their job performance, the personal liability protection afforded to corporate officers and directors, and the extent to which management can resist attempts by outsiders to take over the firm. The resulting array of choices of chartering jurisdictions has been characterized by two competing views: (1) the diversity is desirable because it enables a firm to select a legal domicile whose laws provide the most suitable and most efficient set of contracting opportunities for the firm’s particular circumstances; (2) the diversity is undesirable because it encourages states to compete for incorporations – and reincorporations – by passing laws that appeal to a firm’s managers by insulating them from shareholder pressures and legal actions, and making it difficult for the firm to be taken over without management’s concurrence. Thus, the choice of legal domicile can become an important element in the governance of the firm, and a change of domicile can be a significant event for the firm.

As for many other aspects of corporate decision-making, a natural test as to which of the two characterizations are correct is to observe what happens to the stock prices of companies who reincorporate, on and around the time they do so. The available evidence indicates that reincorporations which result in the firm gaining additional takeover defenses have negative impacts on its stock price – apparently, because investors believe that a takeover and its associated premium price for the firm’s shares will thereby become less likely. Conversely, reincorporations that occasion an increase in the personal liability protection of officers and directors have positive stock price effects. The inference is that such protection makes it easier for the firm to attract qualified directors who can then help management improve the firm’s financial performance. These effects are accentuated when the reincorporation is accompanied by a clear statement from management to the firm’s shareholders about the reasons for the proposed change. There is, therefore, some support for both views of the opportunity for firms to ”shop” for a legal domicile, depending on the associated objective. Other motives for reincorporation seem to have little if any impact on a firm’s stock price, presumably because they are not regarded by investors as material influences on the firm’s performance.