MAASTRICHT TREATY

Treaty agreed to in 1991 and ratified in mid-1993 that committed the 12 member-states of the European Community to a closer economic and political union.

MAINTENANCE MARGIN

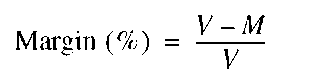

Maintenance margin is the minimum amount of equity that investors must carry in their margin account at all times. It is used to protect the brokerage houses in margin transactions. If the balance falls below the maintenance margin, for example, because of losses on the foreign currency futures contract, a margin call is issued. Enough new money must be added to the account balance to avoid the margin call. The amount of margin is always measured in terms of its relative amount of equity, which is considered the investor’s collateral. The formula for margin is

where V = value of securities and M = margin loan balance (the amount of money being borrowed).

EXAMPLE 75

Consider two cases showing how margin changes:

Case 1: The Original Margin Transaction

| 400 shares at $20 per share using 50% initial margin | Value of securities (V) | $8,000 |

| Margin loan balance (M) | 4,000 | |

| Equity | 4,000 |

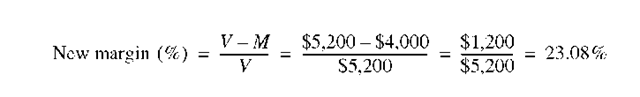

Case 2: Some Time Later

| The price of the 400 shares drops to $13 per share | Value of securities (V) | $5,200 |

| Margin loan balance (M) | 4,000 | |

| Equity | 1,200 |

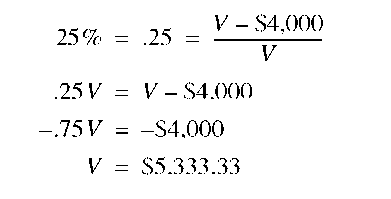

If, for example, the maintenance margin is 25%, this case is subject to a margin call. The investor must put up an extra $133.33 ($5,333.33 – $5,200) to meet the 25% requirement, as computed below.

MANAGED FLOAT

Also called dirty float, a managed float is a country’s attempt to control its currency exchange rates by intervention.

MARGIN

1. Also called performance bond, a margin is the amount of equity used (down payment given) for buying a security or futures contract with the balance being on credit. If you use 25% margin, for example, it means that 25% of the investment position is being financed with your own capital and the balance (75%) with borrowed money.

2. The forward vs. spot rate for a foreign currency.

MARGIN TRADING

Margin trading refers to the use of borrowed funds (financial leverage or debt) to buy securities. It can magnify returns by reducing the amount of capital that must be put up by the investor. The following example illustrates how margin trading can magnify investment returns (ignoring dividends and brokerage commissions).

EXAMPLE 76

| Invested capital (equity) | $4,000 |

| Borrowed funds (margin loan – 50%) | 4,000 |

| Total investment (to purchase 400 shares) | $8,000 |

| Cost to buy 400 shares (at $20 per share) | $8,000 |

| 6 months later—stock sold at $30 per sale—proceeds at sale | 12,000 |

| Gross profit from transaction | $4,000 |

| Less: interest cost (10% per annum) on borrowed funds | 200 |

| $4,000 x 10% x 6/12 | |

| Net profit | $3,800 |

| Return on invested capital | 95% |

| (Net profit/invested capital = $3,800/$4,000) | |

| Annualized return (95% x 12/6) | 190% |

Note: Margin trading is a double-edged sword. The risk of loss is also magnified (by the same rate) when the price of the security falls.

MARKED-TO-MARKET

Futures contracts are marked to market daily. Marked to market is the daily adjustment of margin accounts to reflect profits and losses. At the end of each day, the contracts are settled and the resulting profits or losses paid.

EXAMPLE 77

On Monday morning, you take a long position in a pound futures contract that matures on Wednesday afternoon. The agreed-upon price is $1.68/£ for £62,500. At the close of trading on Monday, the futures price has risen to $1.69. At Tuesday close, the price rises further to $1.70. At Wednesday close, the price falls to $1.685, and the contract matures. You take delivery of the pounds at the prevailing price of $1.685. The daily marked-to-market (settlement) process and your profit (loss) are determined as shown in Exhibit 79.

EXHIBIT 79

Daily Settlement Process

| Time | Action | Cash Flow |

| Monday morning | You buy pound futures contract that matures in two days. Price is $1.68. | None |

| Monday close | Futures price rises to $1.69. Contract is marked-to-market. | You receive: 62,500 x (1.69 – 1.68) = $625 |

| Tuesday close | Futures price rises to $1.70. Contract is marked-to-market. | You receive: 62,500 x (1.70 – 1.69) = $625 |

| Wednesday close

Your net profit is: $1,250 - |

Futures price falls to $1.685.

(1) Contract is marked-to-market (2) Investor takes delivery of £62,500. 937.50 = $312.50. |

(1) You pay:

62,500 x (1.70 -1.685) = $937.50 (2) You pay: £62,500 x 1.685 = $105,312.50 |

MARKET-BASED FORECASTING

Market-based forecasting is the process of developing currency forecasts from market indicators. While this approach is very simple, it is also very effective. The model relies basically on the spot rate or forward rate to forecast the spot rate in the future. The model assumes that the spot rate reflects the foreign exchange rate in the near future. Let us suppose that the Italian lire is expected to depreciate vs. the U.S. dollar. This would encourage speculators to sell lire and later purchase them back at the lower (future) price. This process if continued would drive down the prices of lire until the excess (arbitrage) profits were eliminated.

The model also suggests that the forward exchange rate equals the future spot price. Again, let us suppose that the 90-day forward rate is .987. The market forecasters believe that the exchange rate in 90 days is going to be .965. This provides an arbitrage opportunity. Markets will keep on selling the currency in the forward market until the opportunity for excess profit is eliminated. This model, however, relies heavily on market and market efficiency. It assumes that capital markets and currency markets are highly efficient and that there is perfect information in the marketplace. Under these circumstances, this model can provide accurate forecasts.

Indeed, many of the world currency markets such as the market for U.S. dollar, British pound, and Japanese yen are highly efficient and this model is well suited for such markets. However, market imperfections or lack of perfect information reduces the effectiveness of this model for most currency.

A. Long-Term Forecasting with Forward Rates

While forward rates are sometimes available for two to five years, such rates are rarely quoted. However, the quoted interest rates on risk-free instruments of various countries can be used to determine what the forward rates would be under conditions of interest parity. For example, assume that the U.S. five-year interest rate is 10% annualized, while the British five-year interest rate is 13%. The five-year compounded return on investments in each of these countries is computed as follows:

| Country | Five-Year Compounded Return |

| U.S. (Home) | (1.10)5 – 1 = 61% |

| U.K. (Foreign) | (1.13)5 – 1 = 84% |

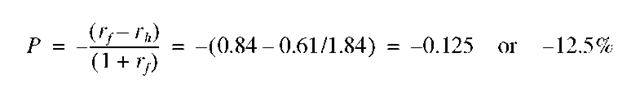

Thus, the appropriate five-year forward rate premium (or discount) of the British pound would be

The results of our computation suggest that the five-year forward rate of the pound should contain a 12.5% discount. That is, the spot rate of the pound is expected to depreciate by 12.5% over the five-year period for which the forward rate is used to forecast.

B. Skepticism about the Forward Rate Forecast

One reason firms might not accept the forward rate as a predictor is because of a second market force. According to interest rate parity, the forward premium (or discount) is determined by the interest rate differential. If, for example, the 30-day interest rate of the British pound is above the 30-day U.S. interest rate, we expect the forward rate on the pound to exhibit a discount. The size of the discount will be such that U.S. investors cannot achieve abnormal returns by using covered interest arbitrage (converting dollars to pounds, investing pounds in a British 30-day account, and simultaneously selling pounds 30 days forward in exchange for dollars). Based on this information, consider that the forward rates of some currencies, such as the British pound and French franc, are usually below their current spot rates. That is, they almost always exhibit a forward discount (because their interest rates are typically above the U.S. rates). The discount within the forward rate suggests that the pound and French franc should depreciate, even when all other factors suggest that these currencies will appreciate.

MARKET EFFICIENCY

Market efficiency requires that all relevant information is quickly reflected in both the spot and forward exchange markets.

MARKET RISK

Market risk is the extent to which the possibility of financial loss can arise from any unfavorable market forces such as changes in interest rates, currency rates, equity prices, or commodity prices. Prices of all securities are correlated to some degree with broad swings in the stock market. Market risk refers to changes in a firm’s security’s price resulting from changes in the stock or bond market as a whole, regardless of the fundamental change in the firm’s earning power.

MARKET-SERVING FDI

A form of foreign direct investment (FDI) by the MNC aimed at targeting the host country.

MARKKA

Finland’s currency.

MIXED FORECASTING

Mixed forecasting in not a unique technique for foreign exchange rate (currency) forecasting but rather a mixture of the three popular approaches—market-based forecasting, fundamental forecasting, and technical forecasting. In some cases, mixed forecasting is nothing but a weighted average of a variety of the forecasting techniques. The techniques can be weighted arbitrarily or by assigning a higher weight to the more reliable technique. Mixed forecasting may often lead to a better result than relying on one single forecast. See also FOREIGN EXCHANGE RATE FORECASTING.

MODIFIED INTERNAL RATE OF RETURN (MIRR)

The modified internal rate of return (MIRR) is defined as the discount rate at which the present value of a project’s cost is equal to the present value of its terminal value, where the terminal value is found as the sum of the future values of the cash flows, compounded at the firm’s cost of capital. The MIRR is a modified version of the internal rate of return (IRR) and a better indicator of relative profitability, hence better for use in capital budgeting. The MIRR has significant advantages over the regular IRR.

• The MIRR assumes that the cash flows from each project are reinvested at the cost of capital rather than at the project’s own IRR. Since reinvestment at the cost of capital is generally more correct and realistic, the MIRR is a better indicator of a project’s true profitability.

• The MIRR solves the multiple IRR problem.

• If two mutually exclusive projects are of equal size and have the same life, NPV and MIRR will always lead to the same ranking. The kinds of conflicts encountered between NPV and the regular IRR will not occur. Example 78 illustrates this points.

EXAMPLE 78

Assume the following:

| Cash Flows Year | |||||

| Projects | 0 | 1 | 2 3 | 4 | 5 |

| A | ($100) | $120 | |||

| B | ($100) | $201.14 |

Computing IRR and NPV at 10% gives the following different rankings:

| Projects | IRR | NPV at 10% |

| A | 20% | $9.01 |

| B | 15 | 24.90 |

The difference in ranking between the two methods is caused by the methods’ reinvestment rate assumptions. The IRR method assumes Project A’s cash inflow of $120 is reinvested at 20% for the subsequent 4 years and the NPV method assumes $120 is reinvested at 10%. The correct decision is to select the project with the higher NPV (Project B), since the NPV method assumes a more realistic reinvestment rate, that is, the cost of capital (10% in this example).

To calculate Project A’s MIRR, first, compute the project’s terminal value at a 10% cost of capital.

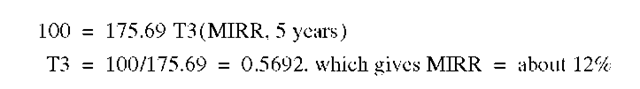

Next, find the IRR by setting:

Now we see the consistent ranking from both the NPV and MIRR methods as shown above.

Note: Microsoft Excel has a function MIRR(values, finance_rate, reinvest_rate).

MONETARY BALANCE

Monetary balance refers to minimizing accounting exposure. It involves avoiding either a net receivable or a net payable position. If an MNC had net positive exposure (more monetary assets than liabilities), it could use more financing from foreign monetary sources to balance things out. MNCs with assets and liabilities in more than one foreign currency may try to reduce risk by balancing off exposure in the different countries. Often, the monetary balance is practiced across several countries simultaneously. Monetary assets and liabilities are those items whose value, expressed in local currency, does not change with devaluation or revaluation. They are listed in Exhibit 80.

| EXHIBIT 80 | |

| Monetary Assets and Liabilities | |

| Monetary Assets | Monetary Liabilities |

| Cash | Accounts payable |

| Marketable securities | Notes payable |

| Accounts receivable | Tax liability reserve |

| Tax refunds receivable | Bonds |

| Notes receivable | Preferred stock |

| Prepaid insurance |

A firm’s monetary balance can be looked at in terms of a firm’s position with regard to real assets. For example, the basic balance sheet equation can be written as follows:

Monetary assets + Real assets = Monetary liabilities + Equity

EXAMPLE 79

| Monetary Assets | Real + Assets | Monetary = Liabilities | Equity + (Net Worth) | |

| Firm A: Monetary creditor | $7,000 | $4,000 | $5,000 | $7,000 |

| Firm B: Monetary debtor | 5,000 | 7,000 | 7,000 | 5,000 |

Firm A is a monetary creditor because its monetary assets exceed its monetary liabilities; its net worth position is negative with respect to its investment coverage of net worth by real assets. In contrast, Firm B is a monetary debtor because it has monetary liabilities that exceed its monetary assets; its net worth coverage by investment in real assets is positive. Thus, the monetary creditor can be referred to as a firm with a negative position in real assets, and the monetary debtor as a firm with a positive position in real assets. Exhibit 81 summarizes these equivalent relationships.

EXHIBIT 81

Monetary Creditor versus Monetary Debitor

| Firm A (Long position | Monetary | Monetary assets | Negative position | Balance of receipts |

| in foreign | creditor | exceed monetary | in real assets | in foreign currency |

| currency) | liabilities | obligations in foreign | ||

| currency is positive | ||||

| Firm B (Short position | Monetary | Monetary liabilities | Positive position | Balance of receipts in |

| in foreign | debtor | exceed monetary | in real assets | foreign currency less |

| currency) | assets | obligations in foreign | ||

| currency is negative |

Thus, if Firm A has a long position in a foreign currency, on balance it will be receiving more funds in foreign currency, or it will have a net monetary asset position that exceeds its monetary liabilities in that currency. The opposite holds for Firm B, which is in a short position with respect to a foreign currency. Hence the analysis with respect to a firm with net future receipts or net future obligations can be applied also to a firm’s balance sheet position. A firm with net receipts is a net monetary creditor. Its foreign exchange rate risk exposure is vulnerable to a decline in value of the foreign currency. On the contrary, a firm with future net obligations in foreign currency is in a net monetary debtor position. The foreign exchange risk exposure it faces is the possibility of an increase in the value of the foreign currency.

In addition to the specific actions of hedging in the forward market or borrowing and lending through the money markets, other business policies can help the firm achieve a balance sheet position that minimizes the foreign exchange rate risk exposure to either currency devaluation or currency revaluation upward. Specifically, in countries whose currency values are likely to fall, local management of subsidiaries should be encouraged to follow these policies:

1. Never have excessive idle cash on hand. If cash accumulates, it should be used to purchase inventory or other real assets.

2. Attempt to avoid granting excessive trade credit or trade credit for extended periods. If accounts receivable cannot be avoided, an attempt should be made to charge interest high enough to compensate for the loss of purchasing power.

3. Wherever possible, avoid giving advances in connection with purchase orders unless a rate of interest is paid by the seller on these advances from the time the subsidiary—the buyer—pays them until the time of delivery, at a rate sufficient to cover the loss of purchasing power.

4. Borrow local currency funds from banks or other sources whenever these funds can be obtained at a rate of interest no higher than U.S. rates adjusted for the anticipated rate of devaluation in the foreign country.

5. Make an effort to purchase materials and supplies on a trade credit basis in the country in which the foreign subsidiary is operating, extending the final date of payment as long as possible.

The reverse polices should be followed in a country where a revaluation upward in foreign currency values is likely to transpire. All these policies are aimed at a monetary balance position in which the firm is neither a monetary debtor nor a monetary creditor. Some MNCs take a more aggressive position. They seek to have a net monetary debtor position in a country whose exchange rates are expected to fall and a net monetary creditor position in a country whose exchange rates are likely to rise.

The monetary/nonmonetary method is a translation method that applies the current exchange rate to all monetary assets and liabilities, both current and long term, while all other assets (physical, or nonmonetary, assets) are translated at historical rates. In contrast with the current/noncurrent method, this method rewards holding of physical assets under devaluation.

MONEY-MARKET HEDGE

Also called credit-market hedge, a money-market hedge is a hedge in which the exposed position in a foreign currency is offset by borrowing or lending in the money market. It basically calls for matching the exposed asset (accounts receivable) with a liability (loan payable) in the same currency. An MNC borrows in one currency, invests in the money market, and converts the proceeds into another currency. Funds to repay the loan may be generated from business operations, in which case the hedge is covered. Or funds to repay the loan may be purchased in the foreign exchange market at the spot rate when the loan matures, which is called an uncovered or open edge. The cost of the money-market hedge is determined by differential interest rates.

EXAMPLE 80

XYZ, an American importer enters into a contract with a British supplier to buy merchandise for £4,000. The amount is payable on the delivery of the good, 30 days from today. The company knows the exact amount of its pound liability in 30 days. However, it does not know the payable in dollars. Assume that the 30-day money-market rates for both lending and borrowing in the U.S. and U.K. are .5% and 1%, respectively. Assume further that today’s foreign exchange rate is $1.50/£. In a money-market hedge, XYZ can make any of the following choices:

1. Buy a one-month U.K. money-market security, worth £4,000/(1 + .005) = £3,980.00. This investment will compound to exactly £4,000 in one month.

2. Exchange dollars on today’s spot (cash) market to obtain the £3,980. The dollar amount needed today is £3,980.00 x $1.50/£ = $5,970.00.

3. If XYZ does not have this amount, it can borrow it from the U.S. money market at the going rate of 1%. In 30 days XYZ will need to repay $5,970.00 x (1 + .01) = $6,029.70.

Note: XYZ need not wait for the future exchange rate to be available. On today’s date, the future dollar amount of the contract is known with certainty. The British supplier will receive £4,000, and the cost of XYZ to make the payment is $6,029.70.

MONEY MARKETS

Money markets are the markets for short-term (less than 1 year) debt securities. Examples of money-market securities include U.S. Treasury bills, federal agency securities, bankers’ acceptances, commercial paper, and negotiable certificates of deposit issued by government, business, and financial institutions.

MULTICURRENCY CROSS-BORDER CASH POOLING

Multicurrency cross-border cash pooling allows a facility to notionally offset debit balances in one currency against credit balances in another. For example, a corporation with credit balances in British pounds and debit balances in German marks and French francs can use pooling to offset the debit and credit balances without the administrative burden of physically moving or converting currencies. The concept of centralized cash pooling is to offset debit and credit balances within a currency and among different currencies without converting the funds physically. Without a centralized pooling system, local subsidiaries lose interest on credit balances or incur higher interest expense on debit balances due to the high margins on interest rates usually taken by local banks. In many cases, credit balances in foreign currency accounts do not earn interest. Through centralized pooling, cash-rich entities pledge their balances so that entities that need to overdraw their cash pool accounts can do so. Credits in one currency may be used to offset debits in another prior to interest calculations—a strategy that often decreases the net amounts borrowed and increases interest yields. The multicurrency system is managed per account on a daily basis. Pooling is based on a zero-balance concept—the volume of credit balances equals the volume of debit balances. When the overall position of all the cash pool accounts is zero or positive, the subsidiaries that are in an overdraft position will actually borrow at credit interest terms. Note: Cash pooling does not eliminate natural interest rate differences between currencies, but it does eliminate the margins on debit balances, thus reducing borrowing costs. Exhibit 82 summarizes goals of the system.

EXHIBIT 82

Reasons for Setting up Cross-Currency Cash Pooling Systems

Optimizing the use of excess cash

Reducing interest expense and maximizing interest yields

Reducing costly foreign exchange, swap transactions, and intercompany transfers Minimizing administrative paper work

Centralizing and speeding information for tighter control and improved decision making

The following example illustrates both the advantages of cash pooling and the return edge provided by a multicurrency approach.

EXAMPLE 81

Assume that three subsidiaries operating in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States maintain multicurrency accounts in the pool. Each has signed an offset agreement with its Amsterdam-based pooling bank. The U.K. company has a local non-interest-bearing DM account. The interbank interest rates are 7.5% for Australian dollars, 4.25% for Deutsche marks, and 5.5% for U.S. dollars. The Australian company’s excess funds in A$ are transferred to its pooling account. The U.K. company has a receivable in DM and has instructed the payor to make the payment directly to its DM pooling account. These pooled credit balances allow other pool members to overdraft their accounts in their preferred currency. For example, the U.S. pooling participant can overdraft its US$ account the countervalue of the available pool balance for investment. Because the overall pooled balance is positive, the pooling mechanism applies credit conditions to all balances in the pool, including debit balances. Consequently, borrowings from the pool are charged interest at credit rates. The positive effect of the pooling is apparent for the U.K. company, which earns interest on its DM balance at 4.25%. Without pooling, no interest would have been earned. Additionally, the U.S. company can borrow from the pool at a rate of 5.5%, which is a credit interest rate.

MULTICURRENCY INTEREST-COMPENSATING DAILY ACCOUNT-MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

The multicurrency interest-compensating daily account-management system (MIDAS) works as follows: Each participating entity sets up its own account(s) at the bank—multicurrency accounts, in many cases, for units that conduct business in more than one currency. Once participating entities open accounts, they must sign offset agreements that permit credit balances in their accounts to be applied against debit balances in sister accounts without transaction approval. The overall net balance should be positive. The overall gain created may be credited to a separate treasury account or allocated among participants according to formulas that take into account participation incentives as well as tax criteria.

MULTILATERAL NETTING

Multilateral netting is an extension of bilateral netting. Under bilateral netting, if a Japanese subsidiary owes a British subsidiary $5 million and the British subsidiary simultaneously owes the Japanese subsidiary $3 million, a bilateral settlement will be made a single payment of $2 million from the Japanese subsidiary to the British subsidiary, the remaining debt being canceled out. Multilateral netting is extended to the transactions between multiple subsidiaries within an international business. It is the strategy used by some MNCs to reduce the number of transactions between subsidiaries of the firm, thereby reducing the total transaction costs arising from foreign exchange dealings with transfer fees. It attempts to maintain balance between receivables and payables denominated in a foreign currency. MNCs typically set up multilateral netting centers as a special department to settle the outstanding balances of affiliates of a multinational company with each other on a net basis. It is the development of a “clearing house” for payments by the firm’s affiliates. If there are amounts due among affiliates they are offset insofar as possible. The net amount would be paid in the currency of the transaction. The total amounts owed need not be paid in the currency of the transaction; thus, a much lower quantity of the currency must be acquired. Note that the major advantage of the system is a reduction of the costs associated with a large number of separate foreign exchange transactions.