Cable is the U.S. dollar per British pound cross rate.

CALL MONEY

1. Money lent by banks to brokers on demand (payable at call).

2. Also called demand money or day-to-day money, interest-bearing deposits payable upon demand. An example is Eurodeposits.

CANADIAN VENTURE EXCHANGE

Canadian Venture Exchange (CDNX) is a product of the merger of the Vancouver and Alberta stock exchanges. The objective of CDNX is to provide venture companies with effective access to capital while protecting investors. This exchange basically contains small-cap Canadian stocks. The CDNX is home to many penny stocks.

CAPITAL ACCOUNT

A capital account is a balance of payment account that records transactions involving the purchase or sale of capital assets. Capital account transactions are classified (e.g., portfolio, direct, or short-term investment).

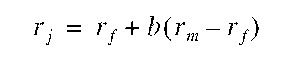

CAPITAL ASSET PRICING MODEL

The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) quantifies the relevant risk of an investment and establishes the trade-off between risk and return (i.e., the price of risk). The CAPM states that the expected return on a security is a function of: (1) the risk-free rate, (2) the security’s systematic risk, and (3) the expected risk premium in the market. The basic message of the model is that risk is priced in a portfolio context. A security risk consists of two components— diversifiable risk and nondiversifiable (or systematic) risk. Diversifiable risk, sometimes called controllable risk or unsystematic risk, represents the portion of a security’s risk that can be controlled through diversification. This type of risk is unique to a given security and thus is not priced. Business, liquidity, and default risks fall into this category. Nondiversifiable risk, sometimes referred to as noncontrollable risk or systematic risk, results from forces outside of the firm’s control and is therefore not unique to the given security. This type of risk must be priced and hence affects the required return on a project. Purchasing power, interest rate, and market risks fall into this category. Nondiversifiable risk is assessed relative to the risk of a diversified portfolio of securities, or the market portfolio. This type of risk is measured by the beta coefficient.

The CAPM relates the risk measured by beta to the level of expected or required rate of return on a security. The model, also called the security market line (SML; see Exhibit 20), is given as follows:

where rj = the expected (or required) return on security i, rf = the risk-free security (such as a T-bill), rm = the expected return on the market portfolio (such as Standard & Poor’s 500 Stock Composite Index), and b = beta, an index of nondiversifiable (noncontrollable, systematic) risk. In words, the CAPM (or SML) equation shows that the required (expected) rate of return on a given security (rj) is equal to the return required for securities that have no risk (rf) plus a risk premium required by investors for assuming a given level of risk. The higher the degree of systematic risk (b), the higher the return on a given security demanded by investors.

EXHIBIT 20 Security Market Line

CAPITAL FLIGHT

Also called capital exports, capital flight is outflows of funds out of a country, typically for fears of economic or political crisis. This may be the result of political or financial crisis, tightening capital controls, tax increases, or fears of a domestic currency devaluation.

CAPITAL MARKETS

Capital markets are the markets for long-term debt and corporate equity issues. The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), which trades the stocks of many of the larger corporations, is a prime example of a capital market. The American Stock Exchange and the regional stock exchanges are also examples. In addition, securities are issued and traded through the thousands of brokers and dealers on the over-the-counter (OTC) market. The capital market is the major source of long-term financing for business and governments. It is an increasingly international one and in any country is not one institution but all those institutions that make up the supply and demand for long-term sources of capital, including the stock exchanges, underwriters, investment bankers, banks, and insurance companies.

CARIBBEAN COMMON MARKET

The Caribbean Common Market (CARICOM) consists of 14 sister-member countries of the Caribbean community: Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Montserrat, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, St. Vincent, Surinam, and Trinidad and Tobago. They have set as a goal that there will be a single market allowing for the free movement of labor. Conspicuous by their absence are the Cayman Islands and the British Virgin Islands, two major players in international banking and finance.

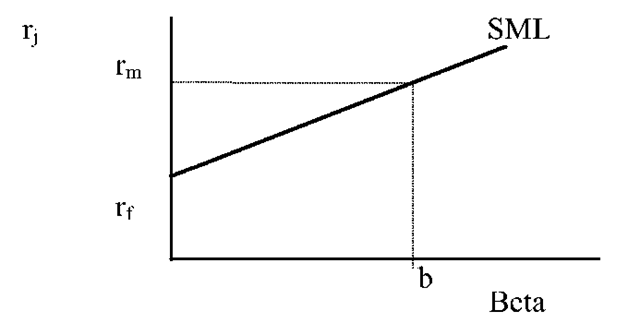

CASH FLOW RETURN ON INVESTMENT

Cash flow return on investment (CFROI), along with economic value added (EVA), is a popular financial metric now embraced by MNCs. Unlike a traditional measure such as return on investment (ROI), CFROI uses cash flow generated by the firm, rather than income or earnings derived from financial statements, as the “return.” The capital base used is also cash investment. The formula is:

CENTRAL BANKS

Central banks are government agencies with authority over the size and growth of the nation’s money supply. They commonly regulate commercial banks, act as the government’s fiscal agent, and are architects of the nation’s monetary policy. Central banks frequently intervene in the foreign exchange markets to smooth fluctuations. For example, the Federal Reserve System is the central bank in the U.S., while the Bundesbank is the central bank of Germany. For the monetary policies and economics performance of central banks, visit the Bank for International Settlements site (http://www.bis.org/cbanks.htm).

CENTRALIZED CASH MANAGEMENT

Centralized cash management is the management practice used by an MNC to place the responsibility for managing corporate cash balances from all affiliates under the custody of a single, central office (normally in New York or London). Centralized cash management offers the following potential gains to the MNC:

1. By pooling the cash holdings of affiliates where possible, it can hold a smaller total amount of cash, thus reducing its financing needs.

2. By centralizing cash management, it can have one group of people specialize in the performance of this task, thus achieving better decisions and economies of scale.

3. By reducing the amount of cash in any affiliate, it can reduce political risks as well as financial costs and enhance profitability.

4. It can net out intracompany accounts when there are multiple payables and receivables among affiliates, thus reducing the amount of money actually transferred among affiliates.

5. All decisions can be made using the overall corporate benefit as the criterion rather than the benefits of individual affiliates, when these might conflict.

The principal disadvantage of centralization is that it brings about both explicit and implicit costs. The explicit costs relate to the added management time and expanded communications required. Implicit costs might insclude that (1) affiliates might resent the tigher control necessary and (2) rigid centralization provides no incentive for local managers to cash in on specific opportunities of which only they may be aware.

CLEARING HOUSE INTERBANK PAYMENT SYSTEM

Clearing House Interbank Payment System (CHIPS) (http://www.chips.org) is a computerized clearing network developed by the New York Clearinghouse Association (http://www.theclear-inghouse.org) for transfer of international dollar payments and settlement of interbank foreign exchange obligations, connecting some 150 depository institutions that have offices or affiliates in New York City. The transfers account for roughly 90% of all interbank transfers regarding international dollar payments.

COCKTAIL SWAP

The cocktail swap is a combination of currency and interest rate swaps, often involving a number of parties, currencies, and interest rates, which leaves the bank unexposed—as long as no default exists or as long as no contract is otherwise terminated prematurely.

COLLAR OPTION

As a form of hybrid option, a collar option involves the simultaneous purchase of a put option and sale of a call option, or vice versa. It is an option that limits the holder’s exposure to a price band. The holder essentially has a call above the cap of that band and a put below its floor.

COMMERCIAL RISK

1. Also called business risk, the likelihood of loss in principal or variations in earnings (or cash flow) of a business due to change in demand and business operations.

2. In banking, the chance that a foreign debtor will fail to repay a loan because of adverse business conditions.

3. In connection with Eximbank guarantees, failure of repayment for reasons other than political factors, such as bankruptcy or insolvency.

4. Uncertainty that the exporter may not be paid for goods or services.

COMMODITY FUTURES TRADING COMMISSION

Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), as created by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission Act of 1974, is the government agency that currently regulates the nation’s commodity futures industry.

COMMON MARKET

Common market is a group of countries seeking a high degree of regional economic integration. It involves: (1) eliminating internal trade barriers and establishing a common external tariff, (2) removing national restrictions on the movement of labor and capital among participating nations and the right of establishment for business firms, and (3) the pursuit of a common external trade policy. The best known is the European Common Market.

COMPANIES ACT OR ORDINANCE

This is legislation enacted by a tax haven to provide for the incorporation, registration, and operation of international business companies (IBCs). More commonly found in the Caribbean tax havens.

COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

Comparative advantage is a theory that everyone gains if each country specializes in the production of those goods that it produces relatively cheaply and more efficiently and imports those goods that other countries make relatively more efficiently. A country is said to have a comparative advantage in the production of such goods and services. This theory is the basis for free trade arguments.

CONFIRMED LETTER OF CREDIT

A letter of credit issued by one bank (a foreign bank) with its authenticity validated by another bank (a U.S. bank) obligating both banks to honor any drafts drawn in compliance. An exporter who requires a confirmed letter of credit from the importer is guaranteed payment from the U.S. bank even if the foreign buyer or bank defaults. It reads, for example, “we hereby confirm this credit and undertake to pay drafts drawn in accordance with the terms and conditions of the letter of credit.”

CONSORTIUM BANK

A consortium bank, a special type of foreign affiliate, is a joint venture, incorporated separately and owned by two or more banks, usually of different nationalities. See also FOREIGN SUBSIDIARIES AND AFFILIATES.

CONTINENTAL TERMS

Foreign exchange rate quotations in foreign currency; the foreign currency price of one U.S. dollar, also called European terms.

CONTINUITY OF CONTRACTS

This principle, backed by European Council (EC) regulation, says contracts cannot be canceled simply because they refer to a currency that is being replaced by the euro.

CONTROLLED FOREIGN CORPORATION

Controlled Foreign Corporation (CFC) is an offshore company which, because of ownership or voting control of U.S. persons, is treated by the Internal Revenue Service as a U.S. tax reporting entity. Sections 951 and 957 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 collectively define the CFC as one in which a U.S. person owns 10% or more of a foreign corporation or in which 50% or more of the total voting stock is owned by U.S. shareholders collectively or 10% or more of the voting control is owned by U.S. persons.

CORRESPONDENT BANK

A bank in one country which, when so required, acts as an agent for a bank in another country, typically formalized by the holding of reciprocal bank accounts. Most major banks maintain correspondent banking relationships with local banks in market areas in which they wish to do business. International correspondent relationships provide international banking services. For example, Citibank of New York may have correspondent relationships with a bank in Cairo, Egypt. Correspondent services include accepting drafts, honoring letters of credit, furnishing credit information, collecting and disbursing international funds, and investing international money-markets funds.

Typically, correspondent services center around paying or collecting international funds because most transactions involve the importing or exporting of goods. In addition, the correspondent bank will provide introductions to local business people. Under a correspondent relationship, the U.S. bank usually will not maintain any permanent personnel in the foreign country; direct contact between the two banks may be limited to periodic conferences between their management to review services provided. In other cases, though, a correspondent relationship will be developed with a local institution even when the American bank has a branch or other presence in the country. This generally occurs when the U.S. bank either is precluded by local law from making, or does not want to make, the necessary investment to clear domestic currency payments in the country.

COST AND FREIGHT (CFR or C&F)

This is a delivery term in which the seller pays for transportation to the destination point. This could be combined with an “on board” instruction specifying when title to the goods changes hands (e.g., FOB).

COST, INSURANCE, AND FREIGHT (CIF)

A term used in the delivery of goods from the exporter to the importer. This is similar to Cost and Freight (CFR or C&F), except the seller must also pay for insurance. Generally this means ocean marine insurance in case the ship sinks or the goods are otherwise damaged by an event other than war. War risk insurance may also be available and is generally paid for by the buyer.

COST OF CAPITAL

Also called a hurdle rate, cutoff rate, or minimum required rate of return, the cost of capital is the rate of return that is necessary to maintain market value (or stock price) of a firm. The firm’s cost of capital is calculated as a weighted average of the costs of debt and equity funds.

It is often called a weighted average of cost of capital (WACC). Equity funds include both capital stock (common stock and preferred stock) and retained earnings. These costs are expressed as annual percentage rates. For example, assume the following capital structure and the cost of each source of financing for a multinational company:

| % of Total | |||

| Source | Book Value | Weights | Cost |

| Debt | $20,000,000 | 40% | 8% |

| Preferred stock | 5,000,000 | 10 | 14 |

| Common stock | 20,000,000 | 40 | 16 |

| Retained earnings | 5,000,000 | 10 | 15 |

| Totals | $50,000,000 | 100% | |

The overall cost of capital is computed as follows: 8%(.4) + 14%(.1) + 16%(.4) + 15%(.1) = 12.5%. The cost of capital is used for capital budgeting purposes. Under the net present value method, the cost of capital is used as the discount rate to calculate the present value of future cash inflows. Under the internal rate of return method, it is used to make an accept-or-reject decision by comparing the cost of capital with the internal rate of return on a given project. A project is accepted when the internal rate exceeds the cost of capital.

COUNTERTRADE

Countertrade is an umbrella term for several sorts of trade in which the seller is required to accept the countervalue of its sale in local goods or services instead of in cash. Payment by a purchaser is entirely or partially in kind instead of hard currencies for products or technology from other countries. It is, therefore, a whole range of barterlike arrangements. More specifically, countertrade has evolved into a diverse set of activities that can be categorized as six distinct types of trading arrangements: (1) barter, (2) counterpurchase, (3) offset, (4) switch trading, (5) compensation or buyback, and (6) clearing account arrangements. Barter is a simple swap of one good for another. In counterpurchase, exporters agree to purchase a quantity of goods from a country in exchange for that country’s purchase of the exporter’s product. The goods being sold by each party are typically unrelated but may be equivalent in value. Offset occurs when the importing nation requires a portion of the materials, components, or subassemblies of a product to be procured in the local (importer’s) market. Switch trading is a complicated form of barter, involving a chain of buyers and sellers in different markets. In a compensation or buy-back deal, exporters of heavy equipment, technology, or even entire facilities agree to purchase a certain percentage of the output of the facility. Clearing account arrangements are used to facilitate the exchange of products over a specified period of time. When the period ends, any balance outstanding must be cleared by the purchase of additional merchandise or settled by a cash payment.

COVERED INTEREST ARBITRAGE

Also called covered investment arbitrage, covered interest arbitrage is an investment in a second currency that is “covered” by a forward sale of that currency to protect against exchange rate fluctuations. More specifically, it involves buying or selling securities internationally and using the forward market to eliminate currency risk in order to take advantage of interest (return) differentials. It is a process whereby one earns a risk-free profit by (1) borrowing currency, (2) converting it into another currency where it is invested, (3) selling this other currency for future delivery against the initial original currency, and (4) using the proceeds of forward sale to repay the original loan. The profits in this transaction depend on interest rate differentials minus the discount or plus the premium on a forward sale.

EXAMPLE 31

Assume that

• The borrowing and lending rates are identical and the bid-ask spread in the spot and forward markets is zero.

• The interest rate on pounds sterling is 12% in London, and the interest rate on a comparable dollar investment in New York is 7%.

• The pound spot rate is $1.75 and the one-year forward rate is $1.68. These rates imply a forward discount on sterling of 4% [(1.68 - 1.75)/1.75] and a covered yield on sterling roughly equal to 8% (12% – 4%).

Because there is a covered interest differential in favor of London, funds will flow from New York to London. That is to say, covered interest arbitrage results.

The following are the steps the arbitrageur can take to profit from the discrepancy in rates based on a $1 million transaction. The arbitrageur will:

1. Borrow $1 million in New York at an interest rate of 7%. This means that at the end of one year, the arbitrageur must repay principal plus interest of $1,070,000.

2. Immediately convert the $1,000,000 to pounds at the spot rate of £1 = $1.75. This yields £571,428.57 ($1,000,000/$1.75) available for investment.

3. Invest the principal of £571,428.57 in London at 12% for one year. At the end of the year, the arbitrageur will have £640,000 (£571,428.57 x 1.12).

4. Simultaneously with the other transactions, sell the £640,000 in principal plus interest forward at a rate of £1 = $1.68 for delivery in one year. This transaction will yield $1,075,200 (£640,000 x $1.68) next year.

5. At the end of the year, collect the £640,000, deliver it to the bank’s foreign exchange department in return for $1,075,200, and use $1,070,000 to repay the loan. The arbitrageur will earn $5,200 on this set of transactions.

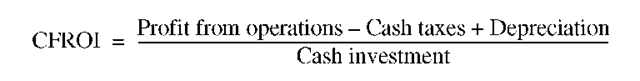

The transactions associated with covered interest arbitrage will affect prices in both the money and foreign exchange markets. As pounds are bought spot and sold forward, boosting the spot rate and lowering the forward rate, the forward discount will tend to widen. Simultaneously, as money flows from New York, interest rates there will tend increase; at the same time, the inflow of funds to London will depress interest rates there. The process of covered interest arbitrage will continue until interest parity is attained, unless there is government interference. To see if a covered interest opportunity exists, use the following steps:

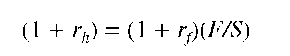

Step 1: Use the interest rate parity (IRP) condition

where F = forward rate, S = spot rate, and rh and rf = home (domestic) and foreign interest rates, and rearrange it to show that the gross returns from investing at home and abroad are equal:

Step 2: Substitute the interest rate and exchange rate data into the above equation. If they are not equal, a covered interest arbitrage opportunity exists. Note: Make sure to convert annualized interest rates into the rates for the time period compatible with forward rates given.

EXAMPLE 32

Suppose the current spot rate of the pound sterling is $1.28, and the 90-day forward rate is $1.30. The 3-month deposit rates in the U.S. and Great Britain are 3% and 4%, respectively. To see if a covered interest opportunity exists, check out the IRT condition.

A covered interest opportunity exists, the IRT condition does not hold (i.e., the gross returns from investing in the U.S. and in Great Britain are not the same). A profit is realized by

(a) Borrowing dollars in the U.S. for 3 months at 3% (or 12% per annum)—$1.03

(b) Convert the dollars into pounds at the spot rate—1/$1.28 = £0.78125

(c) Investing the pounds in a U.K. market for 3 months at 4% (or 16% per annum)—£0.78125 x (1 + 0.4) = £.8125

(d) Simultaneously covering the transactions with a 90-day forward contract to sell pounds at $1.28 – £0.8125 x $1.30/£ = $1.05625. These transactions will result in a gain of $0.02625 ($1.05625 – $1.03). This is equivalent to an annualized gain [or annual percentage rate (APR)] of 10.92%, calculated as

COVERING

Covering refers to buying or selling foreign currencies in amounts equivalent to future payments to be made or received. It is a way of protection against loss due to currency rate movements.

CREATION OF EURODOLLARS

How Eurodollars are created can be explained, step by step, by using a series of T-accounts to trace the movement of dollars into and through the Eurodollar market. Eurodollar creation involves a chain of deposits between the original depositor and the U.S. bank, and the transfer of control over the deposits from one Eurobank to another.

EXAMPLE 33

Assume that Henteleff and Co. in New York decides to shift $1 million out of its NY bank time deposit and into a time deposit with a Eurobank in London. Transfer of the dollar deposit from the NY bank to the London bank creates a Eurodollar deposit.

1st stage:

| First Eurobank | |

| Demand deposit | $1M Eurodollar |

| time deposit due to | |

| Henteleff | |

2nd Stage: If First Eurobank does not immediately have a commercial borrower or government to which it can loan the funds, First Eurobank will place the $M in the Eurodollar interbank market.

| First Eurobank | Second Eurobank | ||

| Eurodollar $1M | $1M Eurodollar | Demand deposit in | $1M Eurodollar time |

| deposit in Second | deposit due to | the NY bank | deposit due to First |

| Eurobank | Henteleff | Eurobank | |

3rd Stage: Eurobank needs the funds to lend Mr. Borrower.

| Second Eurobank | |

| Loan to Mr. | $1M Eurodollar |

| Borrower $1M | time deposit due |

| to Eurobank | |

Note: U.S. money supply is constant at $1 million, but the world’s money supply is increased to $2 million (Henteleff and First Eurobank’s $2 million deposits).

CREDIT RISK

Also called default risk, credit risk is the chance that a trading partner will default on a contract.

CREDIT SWAP

A credit swap is an exchange of currencies between an MNC and a bank (frequently a central bank) of a foreign country that is to be reversed by agreement at a later date. This is widely used, particularly where local credit is not available and where there is no forward exchange market. The basic advantage of the credit swap is the ability to minimize the risk and the cost of financing operations in a weak-currency country.

CROSS-CURRENCY SWAP

Also called circus swap, the cross-currency swap is a currency swap combined with an interest rate swap (floating versus fixed rate), in the sense that the loans on which the service schedules are based differ by currency and type of interest payment.

CROSS INVESTMENT

Cross investment is a type of foreign direct investment made, as a defense measure, by oligopolistic companies in each other’s home country.

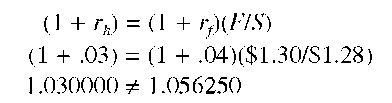

CROSS RATE

The exchange rate between two currencies derived by dividing each currency’s exchange rate with a third currency. For example, if dollars per pound is $1.5999/£ and yens per dollar is ¥110.66/$, the cross rate between Japanese yen and British pounds is

Because most currencies are quoted against the dollar, it may be necessary to work out the cross rates for currencies other than the dollar. The cross rate is needed to consummate financial transactions between two countries.

| KEY CURRENCY CROSS RATES 21 Feb 2000 | ||||

| British Euro | British

1.6203 |

Euro

0.6172 |

Japan

0.5653 0.9153 |

U.S.

0.6250 1.0129 |

| Japan | 177.05 | 109.25 | — | 110.66 |

| U.S. | 1.5999 | 0.9873 | 0.9037 | — |

Note: Cross currency table calculator can be accessed by http://www.xe.net/currency/table.htm.

CUMULATIVE TRANSLATION ADJUSTMENT ACCOUNT

Cumulative translation adjustment (CTA) account is an entry in a translated balance sheet in which gains and/or losses from currency translation have been accumulated over a period of years.

CURRENCY ARBITRATE

Currency arbitrate is a form of arbitrage that takes advantage of divergences in exchange rates in different money markets by buying a currency in one market and selling it in another.

CURRENCY BOARD

A currency board is a government institution that exchanges domestic currency for foreign currency at a fixed rate of exchange. Under a currency board system, there is no central bank. The board has no discretionary monetary policy. Instead, market forces alone determine the money supply. The board attempts, however, to promote price stability and follow a responsible fiscal policy.

CURRENCY COCKTAIL BOND

A bond denominated in a blend (or cocktail) of currencies.

CURRENCY DIVERSIFICATION

Currency diversification is the practice aimed at slashing the impact of unforeseen currency fluctuations by engaging activities in a portfolio of different currencies. Exposure to a diversified currency portfolio normally results in less currency risk than if all of the exposure was in one foreign currency.

CURRENCY FORECASTING

The idea of cutting the impact of unforeseen currency fluctuations by engaging activities in a portfolio of different currencies.

CURRENCY FUTURES CONTRACT

A currency futures contract is a contract for future delivery of a specific quantity of a given currency, with the exchange rate fixed at the time the contract is entered. Futures contracts are similar to forward contracts except that they are standardized and traded on the organized exchanges and the gains and losses on the contracts are settled each day. See also FOREIGN CURRENCY FUTURES; FOREIGN CURRENCY FUTURES; FORWARD CONTRACTS.

CURRENCY INDEXES

Currency indexes are economic indicators that attempt to measure foreign currencies. Two popular currency indexes are:

• Federal Reserve Trade-Weighted Dollar: The index reflects the currency units of more than 50% of the U.S. purchase, principal trading countries.The index measures the currencies of ten foreign countries: the United Kingdom, Germany, Japan, Italy, Canada, France, Sweden, Switzerland, Belgium, and the Netherlands. The index is weighted by each currency’s base exchange rate and then averaged on a geometric basis. This weighting process indicates relative significance in overseas markets. The base year was 1973. The index is published by the Federal Reserve System and is found in its Federal Reserve Bulletin or at various Federal Reserve Internet sites such as http://woodrow.mpls.frb.fed.us/economy. The MNC should examine the trend in this index to determine foreign exchange risk exposure associated with its investment portfolio and financial positions. Also, the Federal Reserve trade-weighted dollar is the basis for commodity futures on the New York Cotton Exchange.

• J.P. Morgan Dollar Index: The index measures the value of currency units versus dollars. The index is a weighted-average of 19 currencies including those of France, Italy, United Kingdom, Germany, Canada, and Japan. The weighting is based on the relative significance of the currencies in world markets. The base of 100 was established for 1980 through 1982. The index highlights the impact of foreign currency units in U.S. dollar terms. The MNC can see the effect of foreign currency conversion on U.S. dollar investment.

CURRENCY OPTION

Foreign currency options are financial contracts that give the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy (or sell) a specified number of units of foreign currency from the option seller at a fixed dollar price, up to the option’s expiration date. In return for this right the buyer pays a premium to the seller of the option. They are similar to foreign currency futures, in that the contracts are for fixed quantities of currency to be exchanged at a fixed price in the future. The key difference is that the maturity date for an option is only the last day to carry out the currency exchange; the option may be “exercised,” that is, presented for currency exchange, at any time between its issuance and the maturity date, or not at all. Currency options are used as a hedging tool and for speculative purposes.

EXAMPLE 34

The buyer of a call option on British pounds obtains the right to buy £50,000 at a fixed dollar price (i.e., the exercise price) at any time during the (typically) three-month life of the option. The seller of the same option faces a contingent liability in that the seller will have to deliver the British pounds at any time, if the buyer chooses to exercise the option. The market value of an option depends on its exercise price, the remaining time to its expiration, the exchange rate in the spot market, and expectations about the future exchange rate. An option may sell for a price near zero or for thousands of dollars, or anywhere in between. Notice that the buyer of a call option on British pounds may pay a small price to obtain the option but does not have to exercise the option if the actual exchange rate moves favorably. Thus, an option is superior to a forward contract having the same maturity and exercise price because it need not be used—and the cost is just its purchase price. However, the price of the option is generally greater than the expected cost of the forward contract; so the user of the option pays for the flexibility of the instrument.

A. Currency Option Terminology

Foreign currency option definitions are as follows.

1. The amount is how much of the underlying foreign currency involved.

2. The seller of the option is referred to as the writer or grantor.

3. A call is an option to buy foreign currency, and a put is an option to sell foreign currency.

4. The exercise or strike price is the specified exchange rate for the underlying currency at which the option can be exercised.

• At the money—exercise price equal to the spot price of the underlying currency. An option that would be profitable if exercised immediately is said to be in the money.

• In the money—exercise price below the current spot price of the underlying currency, while in-the-money puts have an exercise price above the current spot price of the underlying currency.

• Out of the money—exercise price above the current spot price of the underlying currency, while out-of-the-money puts have an exercise price below the current spot price of the underlying currency. An option that would not be profitable if exercised immediately is referred to as out of the money.

5. There are broadly two types of options: American option can be exercised at any time between the date of writing and the expiration or maturity date and European option can be exercised only on its expiration date, not before.

6. The premium or option price is the cost of the option, usually paid in advance by the buyer to the seller. In the over-the-counter market, premiums are quoted as a percentage of the transaction amount. Premiums on exchange-traded options are quoted as a dollar (domestic currency) amount per unit of foreign currency.

B. Foreign Currency Options Markets

Foreign currency options can be purchased or sold in three different types of markets:

1. Options on the physical currency, purchased on the over-the-counter (interbank) market;

2. Options on the physical currency, purchased on an organized exchange such as the Philadelphia Stock Exchange; and

3. Options on futures contracts, purchased on the International Monetary Market (IMM).

B.1. Options on the Over-the-Counter Market

Over-the-counter (OTC) options are most frequently written by banks for U.S. dollars against British pounds, German marks, Swiss francs, Japanese yen, and Canadian dollars. They are usually written in round lots of $85 to $10 million in New York and $2 to 83 million in London. The main advantage of over-the-counter options is that they are tailored to the specific needs of the firm. Financial institutions are willing to write or buy options that vary by amount (national principal), strike price, and maturity. Although the over-the-counter markets were relatively illiquid in the early years, the market has grown to such proportions that liquidity is now considered quite good. On the other hand, the buyer must assess the writing bank’s ability to fulfill the option contract. Termed counterparty risk, the financial risk associated with the counterparty is an increasing issue in international markets. Exchange-traded options are more the sphere of the financial institutions themselves. A firm wishing to purchase an option in the over-the-counter market normally places a call to the currency option desk of a major money center bank, specifies the currencies, maturity, strike rate(s), and asks for an indication, a bid-offer quote.

B.2. Options on Organized Exchanges

Options on the physical (underlying) currency are traded on a number of organized exchanges worldwide, including the Philadelphia Stock Exchange (PHLX) and the London International Financial Futures Exchange (LIFFE). Exchange-traded options are settled through a clearinghouse, so that buyers do not deal directly with sellers. The clearinghouse is the counterparty to every option contract and it guarantees fulfillment. Clearinghouse obligations are in turn the obligation of all members of the exchange, including a large number of banks. In the case of the Philadelphia Stock Exchange, clearinghouse services are provided by the Options Clearing Corporation (OCC).

The Philadelphia Exchange has long been the innovator in exchange-traded options and has in recent years added a number of unique features to its United Currency Options Market (UCOM) making exchange-traded options much more flexible—and more competitive—in meeting the needs of corporate clients. UCOM offers a variety of option products with standardized currency options on eight major currencies and two cross-rate pairs (non-U.S. dollar), with either American- or European-style pricing. The exchange also offers customized currency options, in which the user may choose exercise price, expiration date (up to two years), and premium quotation form (units of currency or percentage of underlying value). Cross-rate options are also available for the DM/¥ and £/DM. By taking the U.S. dollar out of the equation, cross-rate options allow one to hedge directly the currency risk that arises in dealing with nondollar currencies. Contract specifications are shown in Exhibit 21. The PHLX trades both American-style and European-style currency options. It also trades month-end options (listed as EOM, or end of month), which ensures the availability of a short-term (at most, a two- or sometimes three-week) currency option at all times and long-term options, which extend the available expiration months on PHLX dollar-based and cross-rate contracts providing for 18- and 24-month European-style options. In 1994, the PHLX introduced a new option contract, called the Virtual Currency Option, which is settled in U.S. dollars rather than in the underlying currency.

EXHIBIT 21

Philadelphia Stock Exchange Currency Option Specifications

| Austrian | British | Canadian | Deutsche | Japanese | |||

| Dollar | Pound | Dollar | Mark | Swiss Franc | Euro | Yen | |

| Symbol | |||||||

| American | XAD | XBP | XCD | XDM | SXF | XEU | XJY |

| European | CAD | CBP | CCD | CDM | CSF | ECU | CJY |

| Contract size | A$50,000 | £31,250 | C$50,000 | DM 62,500 | SFr 62,500 | €62,500 | ¥6,250,000 |

| Exercise Price | 10 | 2.50 | 0.50 | 101 | 101 | 20 | 0.0101 |

| Intervals | |||||||

| Premium | Cents per | Cents per | Cents per | Cents per | Cents per | Cents per | Hundredths |

| Quotations | unit | unit | unit | unit | unit | unit | of a cent |

| per unit | |||||||

| Minimum Price | $0.(00)01 | $0.(00)01 | $0.(00)01 | $0.(00)01 | $0.(00)01 | $0.(00)02 | $0.(00)01 |

| Change | |||||||

| Minimum | $5.00 | $3.125 | $5.00 | $6.25 | $6.25 | $6.25 | $6.25 |

| Contract Price | |||||||

| Change | |||||||

| Expiration | March, June, September, and December + two near | term months | |||||

| Months | |||||||

| Exercise Notice | No automatic exercise of in-the-money options | ||||||

| Expiration Date | Friday before third Wednesday of the month (Friday is also the last trading day) | ||||||

| Expiration | Third Wednesday of month | ||||||

| Settlement Date | |||||||

| Daily Price | None | ||||||

| Limits | |||||||

| Issuer & | Options Clearing Corporation (OCC) | ||||||

| Guarantor | |||||||

| Margin for | Option premium plus 4% of the underlying contract value less out-of-money amount, if any, | ||||||

| Uncovered | to a minimum of the option premium plus 3/4% of the underlying contract value. | ||||||

| Writer | Contract value equal spot price times unit of currency per contract. | ||||||

| Position & | 100,000 contracts | ||||||

| Exercise Limits | |||||||

| Trading Hours | 2:30 A.M.-2:30 P.M. Philadelphia time, Monday through Friday2 | ||||||

| Taxation | Any gain or loss: | 60% long-term/40% short-term | |||||

1 Half-point strike prices (0.50) for SFr (0.50), and ¥ (0.0050) in the three near-term months only.

2 Trading hours for the Canadian dollar are 7:00 A.M.-2:30 P.M. Philadelphia time, Monday through Friday.

B.3. Currency Option Quotations and Prices

Some recent currency option prices from the Philadelphia Stock Exchange are presented in Exhibit 22. Quotations are usually available for more combinations of strike prices and expiration dates than were actually traded and thus reported in the newspaper such as the Wall Street Journal. Exhibit 22 illustrates the three different prices that characterize any foreign currency option. Note: Currency option strike prices and premiums on the U.S. dollar are quoted here as direct quotations ($/DM, $/¥, etc.) as opposed to the more common usage of indirect quotations used throughout the topic. This approach is standard practice with option prices as quoted on major option exchanges like the Philadelphia Stock Exchange.

The three prices that characterize an “August 48 1/2 call option” are the following:

EXHIBIT 22

Foreign Currency Option Quotations (Philadelphia Stock Exchange)

| Option and Underlying | Calls—Last | Puts—Last | |||||

| Strike Price | Aug. | Sept. | Dec. | Aug. | Sept. | Dec. | |

| 62.500 German | Cents per | ||||||

| marks | unit | ||||||

| 48.51 | 46 | — | — | 2.76 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 1.16 |

| 48.51 | 46 1/2 | — | — | — | 0.06 | 0.30 | — |

| 48.51 | 47 | 1.13 | — | 1.74 | 0.10 | 0.38 | 1.27 |

| 48.51 | 47 1/2 | 0.75 | — | — | 0.17 | 0.55 | — |

| 48.51 | 48 | 0.71 | 1.05 | 1.28 | 0.27 | 0.89 | 1.81 |

| 48.51 | 48 1/2 | 0.50 | — | — | 0.50 | 0.99 | — |

| 48.51 | 49 | 0.30 | 0.66 | 1.21 | 0.90 | 1.36 | — |

| 48.51 | 49 1/2 | 0.15 | 0.40 | — | 2.32 | — | — |

| 48.51 | 50 | — | 0.31 | — | 2.32 | 2.62 | 3.30 |

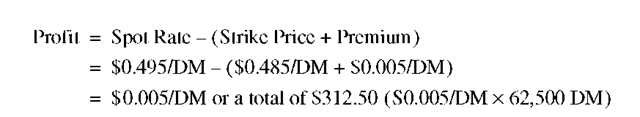

1. Spot rate. In Exhibit 22, “option and underlying” means that 48.51 cents, or $0.4851, was the spot dollar price of one German mark at the close of trading on the preceding day.

2. Exercise price. The exercise price or “strike price” listed in Exhibit 22 means the price per mark that must be paid if the option is exercised. The August call option on marks of 48 1/2 means $0.4850/DM. Exhibit 22 lists nine different strike prices, ranging from $0.4600/DM to $0.5000/DM, although more were available on that date than are listed here.

3. Premium. The premium is the cost or price of the option. The price of the August 48 1/2 call option on German marks was 0.50 U.S. cents per mark, or $0.0050/DM. There was no trading of the September and December 48 1/2 call on that day. The premium is the market value of the option. The terms premium, cost, price, and value are all interchangeable when referring to an option. All option premiums are expressed in cents per unit of foreign currency on the Philadelphia Stock Exchange except for the French franc, which is expressed in tenths of a cent per franc, and the Japanese yen, which is expressed in hundredths of a cent per yen.

The August 48 1/2 call option premium was 0.50 cents per mark, and in this case, the August 48 1/2 put premium was also 0.50 cents per mark. As one option contract on the Philadelphia Stock Exchange consists of 62,500 marks, the total cost of one option contract for the call (or put in this case) is DM62,500 x $0.0050/DM = $312.50.

B.4. Speculating in Option Markets

Options differ from all other types of financial instruments in the patterns of risk they produce. The option owner has the choice of exercising the option or allowing it to expire unused. The owner will exercise it only when exercising is profitable, which means when the option is in the money. In the case of a call option, as the spot price of the underlying currency moves up, the holder has the possibility of unlimited profit. On the downside, however, the holder can abandon the option and walk away with a loss never greater than the premium paid.

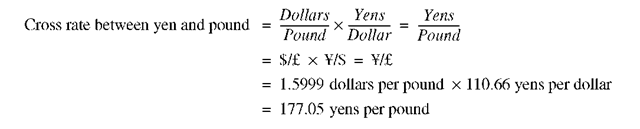

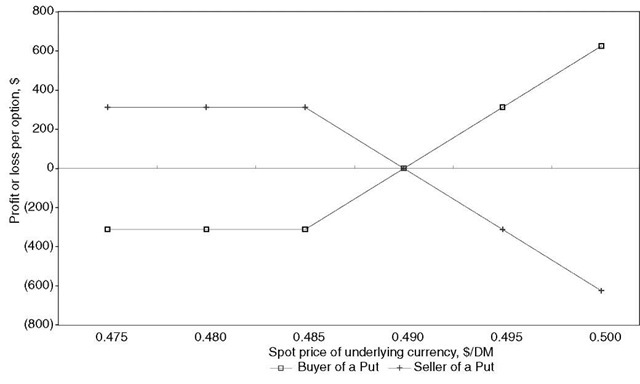

C. Buyer of a Call

To see how currency options might be used, consider a U.S. importer, called MYK Corporation with a DM 62,500 payment to make to a German exporter in two months (see Exhibit 23). MYK could purchase a European call option to have the DMs delivered to him at a specified exchange rate (the exercise price) on the due date. Assume that the option premium is $0.005/DM, and the strike price is 48 1/2 ($0.4850/DM). MYK has paid $312.50 for a DM 48 1/2 call option, which gives him the right to buy DM 62,500 at a price of $0.4850 per mark at the end of two months. Exhibit 24 illustrates the importer’s gains and losses on the call option. The vertical axis measures profit or loss for the option buyer, at each of several different spot prices for the mark up to the time of maturity.

At all spot rates below (out-of-the-money) the strike price of $0.485, MYK would choose not to exercise its option. This decision is obvious, since at a spot rate of $0.485, for example, MYK would prefer to buy a German mark for $0.480 on the spot market rather than exercise his option to buy a mark at $0.485. If the spot rate remains below $0.480 until August when the option expires, he would not exercise the option. His total loss would be limited to only what he paid for the option, the $0.005/DM purchase price. At any lower price for the mark, his loss would similarly be limited to the original $0.005/DM cost.

Alternatively, at all spot rates above (in-the-money) the strike price of $0.485, MYK would exercise the option, paying only the strike price for each German mark. For example, if the spot rate were $0.495 cents per mark at maturity, he would exercise his call option, buying German marks for $0.485 each instead of purchasing them on the spot market at $0.495 each. The German marks could be sold immediately in the spot market for $0.495 each, with MYK pocketing a gross profit of $0.0010/DM, or a net profit of $0.005/DM after deducting the original cost of the option of $0.005/DM for a total profit of $312.50 ($0.005/DM x 62,500 DM). The profit to MYK, if the spot rate is greater than the strike price, with a strike price of $0.485, a premium of $0.005, and a spot rate of $0.495, is

More likely, MYK would realize the profit by executing an offsetting contract on the options exchange rather than taking delivery of the currency. Because the dollar price of a mark could rise to an infinite level (off the upper right-hand side of Exhibit 24), maximum profit is unlimited. The buyer of a call option thus possesses an attractive combination of outcomes: limited loss and unlimited profit potential.

The break-even price at which the gain on the option just equals the option premium is $0.490/DM. The premium cost of $0.005, combined with the cost of exercising the option of $0.485, is exactly equal to the proceeds from selling the marks in the spot market at $0.490. Note that MYK will still exercise the call option at the break-even price. By exercising it MYK at least recovers the premium paid for the option. At any spot price above the exercise price but below the break-even price, the gross profit earned on exercising the option and selling the underlying currency covers part (but not all) of the premium cost.

D. Writer of a Call

The position of the writer (seller) of the same call option is illustrated in the bottom half of Exhibit 23. Because this is a zero-sum game, the profit from selling a call, shown in Exhibit 23, is the mirror image of the profit from buying the call. If the option expires when the spot price of the underlying currency is below the exercise price of $0.485, the holder does not exercise the option. What the holder loses, the writer gains. The writer keeps as profit the entire premium paid of $0.005/DM. Above the exercise price of $0.485, the writer of the call must deliver the underlying currency for $0.485/DM at a time when the value of the mark is above $0.485. If the writer wrote the option naked—that is, without owning the currency—that seller will now have to buy the currency at spot and take the loss. The amount of such a loss is unlimited and increases as the price of the underlying currency rises. Once again, what the holder gains, the writer loses, and vice versa. Even if the writer already owns the currency, the writer will experience an opportunity loss, surrendering against the option the same currency that could have been sold for more in the open market.

For example, the loss to the writer of a call option with a strike price of $0.485, a premium of $0.005, and a spot rate of $0.495/DM is

but only if the spot rate is greater than or equal to the strike rate. At spot rates less than the strike price, the option will expire worthless and the writer of the call option will keep the premium earned. The maximum profit that the writer of the call option can make is limited to the premium. The writer of a call option would have a rather unattractive combination of potential outcomes: limited profit potential and unlimited loss potential. Such losses can be limited through other techniques.

EXHIBIT 23

Profit or Loss For Buyer and Seller of a Call Option

| Contract size: | 62,500 | DM | ||||

| Expiration date: | 2 | months | ||||

| Exercise, or strike price: | 0.4850 | $/DM | ||||

| Premium, or optionprice: | 0.0050 | $/DM | ||||

| Profit | or Loss for Buyer of a | Call Option | ||||

| Ending Spot | 0.475 | 0.480 | 0.485 | 0.490 | 0.495 | 0.500 |

| Rate ($/DM) | ||||||

| Payments: | ||||||

| Premium | (313) | (313) | (313) | (313) | (313) | (313) |

| Exercise cost | 0 | 0 | 0 | (30,313) | (30,313) | (30,313) |

| Receipts: | ||||||

| Spot sale of DM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30,625 | 30,938 | 31,250 |

| Net ($): | (313) | (313) | (313) | 0 | 313 | 625 |

Profit or Loss for Seller of a Call Option

The writer of an option profits when the buyer of the option suffers losses, i.e., a zero-sum game. The net position of the writer is, therefore, the negative of the position of the holder.

| Net ($): | 313 | 313 | 313 | 0 | (313) | (625) |

EXHIBIT 24

German Mark Call Option (Profit or Loss Per Option)

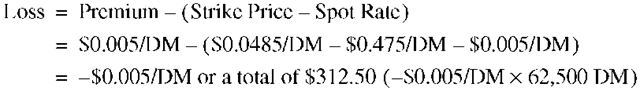

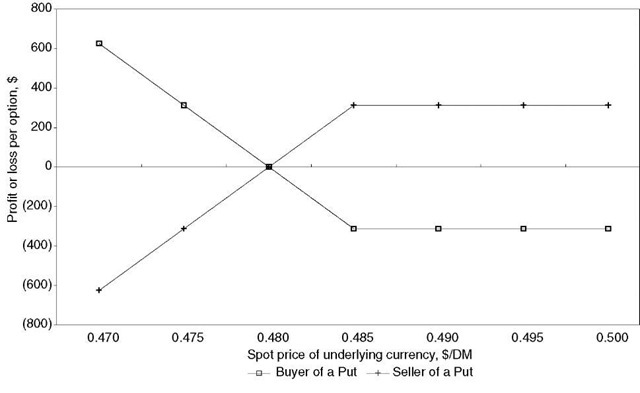

E. Buyer of a Put

The position of MYK as buyer of a put is illustrated in Exhibit 25. The basic terms of this put are similar to those just used to illustrate a call. The buyer of a put option, however, wants to be able to sell the underlying currency at the exercise price when the market price of that currency drops (not rises as in the case of a call option). If the spot price of a mark drops to, say, $0.475/DM, MYK will deliver marks to the writer and receive $0.485/DM. Because the marks can now be purchased on the spot market for $0.475 each and the cost of the option was $0.005/DM, he will have a net gain of $0.005/DM. Explicitly, the profit to the holder of a put option if the spot rate is less than the strike price, with a strike price of $0.485/DM, a premium of $0.005/DM, and a spot rate of $0.475/DM is

The break-even price for the put option is the strike price less the premium, or $0.480/DM in this case. As the spot rate falls further below the strike price, the profit potential would increase, and MYK’s profit could be unlimited (up to a maximum of $0.480/DM, when the price of a DM would be zero). At any exchange rate above the strike price of $0.485, MYK would not exercise the option, and so would have lost only the $0.005/DM premium paid for the put option. The buyer of a put option has an almost unlimited profit potential with a limited loss potential. Like the buyer of a call, the buyer of a put can never lose more than the premium paid up front.

F. Writer of a Put

The position of the writer of the put sold to MYK is shown in the lower portion of Exhibit 25. Note the symmetry of profit/loss, strike price, and break-even prices between the buyer and the writer of the put, as was the case of the call option. If the spot price of marks drops below $0.485 per mark, the option will be exercised by MYK. Below a price of $0.480 per mark, the writer will lose more than the premium received from writing the option ($0.005/DM), falling below break-even. Between $0.480/DM and $0.485/DM the writer will lose part, but not all, of the premium received. If the spot price is above $0.485/DM, the option will not be exercised, and the option writer pockets the entire premium of $0.005/DM. The loss incurred by the writer of a $0.485 strike price put, premium $0.005, at a spot rate of $0.475, is

but only for spot rates that are less than or equal to the strike price. At spot rates that are greater than the strike price, the option expires out-of-the-money and the writer keeps the premium earned up-front. The writer of the put option has the same basic combination of outcomes available to the writer of a call: limited profit potential and unlimited loss potential up to a maximum of $0.480/DM.

EXHIBIT 25

Profit or Loss for Buyer and Seller of a Put Option

| Contract size: | 62,500 | DM | |||||

| Expiration date: | 2 | months | |||||

| Exercise, or strike | price: | 0.4850 | $/DM | ||||

| Premium, or option price: | 0.0050 | $/DM | |||||

| Profit or Loss | for Buyer | of a Put Option | |||||

| Ending Spot | 0.470 | 0.475 | 0.480 | 0.485 | 0.490 | 0.495 | 0.500 |

| Rate ($/DM) | |||||||

| Payments: | |||||||

| Premium | (313) | (313) | (313) | (313) | (313) | (313) | (313) |

| Spot Purchase | (29.375) | (29,688) | (30,000) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| of DM | |||||||

| Receipts: | |||||||

| Exercise of | 30,313 | 30,313 | 30,313 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| option | |||||||

| Net ($): | 625 | 313 | 0 | (313) | (313) | (313) | (313) |

Profit or Loss for Seller of a Put Option

The writer of an option profits when the holder of the option suffers losses, i.e., a zero-sum game. The net position of the writer is, therefore, the negative of the position of the holder.

| Net ($): | (625) | (313) | 0 | 313 | 313 | 313 | 313 |

EXHIBIT 26

German Mark Put Option (Profit or Loss Per Option)

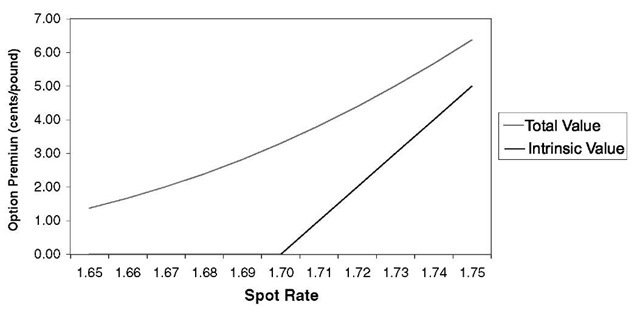

G. Option Pricing and Valuation

Exhibit 27 illustrates the profit/loss profile of a European-style call option on British pounds. The call option allows the holder to buy British pounds (£) at a strike price of $1.70/£. The value of this call option is actually the sum of two components:

Intrinsic value is the financial gain if the option is exercised immediately. It is shown by the solid line in Exhibit 28, which is zero until reaching the strike price, then rises linearly (1 cent for each 1 cent increase in the spot rate). Intrinsic value will be zero when the option is out-of-the-money—that is, when the strike price is above the market price—as no gain can be derived from exercising the option. When the spot price rises above the strike price, the intrinsic value becomes positive because the option is always worth at least this value if exercised. The time value of an option exists since the price of the underlying currency, the spot rate, can potentially move further in-the-money between the present time and the option’s expiration date.

EXHIBIT 27

Intrinsic Value, Time Value, Total Value of a Call Option on British Pounds

| Intrinsic Value | Time Value | |||

| Spot($/£) | Strike Price | of Option | of Option | Total Value |

| (1) | (2) | (1) – (2) = (3) | (4) | (3) + (4) = (5) |

| 1.65 | 1.70 | 0.00 | 1.37 | 1.37 |

| 1.66 | 1.70 | 0.00 | 1.67 | 1.67 |

| 1.67 | 1.70 | 0.00 | 2.01 | 2.01 |

| 1.68 | 1.70 | 0.00 | 2.39 | 2.39 |

| 1.69 | 1.70 | 0.00 | 2.82 | 2.82 |

| 1.70 | 1.70 | 0.00 | 3.30 | 3.30 |

| 1.71 | 1.70 | 1.00 | 2.82 | 3.82 |

| 1.72 | 1.70 | 2.00 | 2.39 | 4.39 |

| 1.73 | 1.70 | 3.00 | 2.01 | 5.01 |

| 1.74 | 1.70 | 4.00 | 1.67 | 5.67 |

| 1.75 | 1.70 | 5.00 | 1.37 | 6.37 |

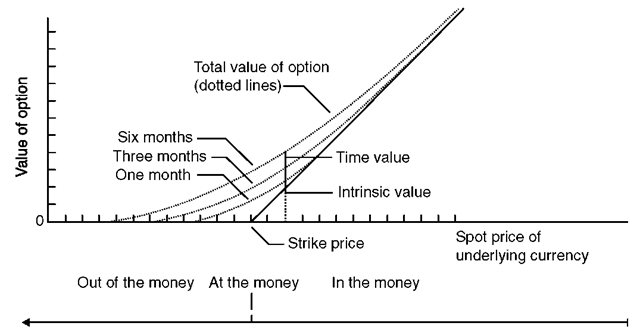

Note from Exhibit 28 that the time value of a call option varies with option contract periods.

EXHIBIT 28

Intrinsic Value, Time Value, Total Value of a Call Option on British Pounds

Note from Exhibit 29 that the time value of a call option varies with option contract periods.

EXHIBIT 29

The Value of a Currency Call Option before Maturity

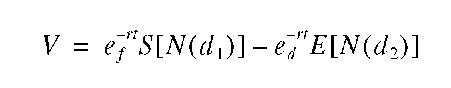

CURRENCY OPTION PRICING

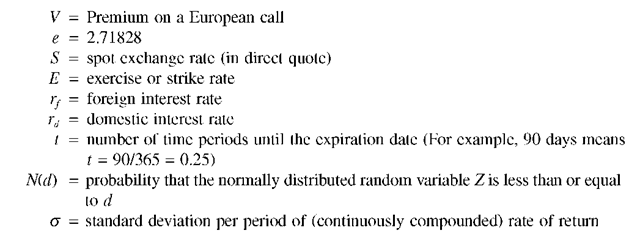

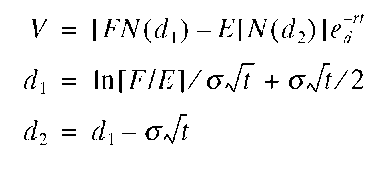

Based on the work of Black and Scholes and others, the model yields the option premium. The basic theoretical model for the pricing of a European call option is:

where

The two density functions, d1 and d2, and the formula are determined as follows:

Note: In the final derivations, the spot rate (S) and foreign interest rate (rf) have been replaced with the forward rate (F ).

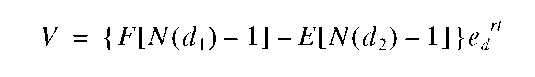

The premium for a European put option is similarly derived:

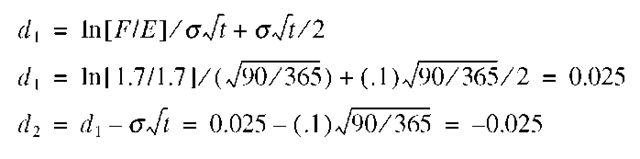

EXAMPLE 35

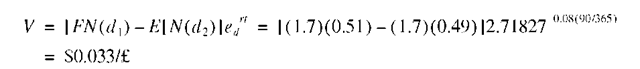

Given the following data on basic exchange rate and interest rate values:

EXAMPLE 35

Given the following data on basic exchange rate and interest rate values:

| Data | Symbols | Numerical values |

| Spot rate | S | $1.7/£ |

| 90-day forward | F | $1.7/£ |

| Exercise or strike rate | E | $1.7/£ |

| U.S. interest rate | rd | 0.08 = 8% |

| British pound interest rate | rf | 0.08 = 8% |

| Time | t | 90/365 |

| Standard deviation | a | 0.01 = 10% |

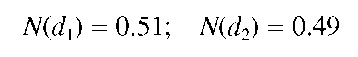

The values of dl and d2 are found from the normal distribution table.

Substituting these values into the option premium formula yields:

CURRENCY OPTION PRICING SENSITIVITY

If currency options are to be used effectively for hedging or speculative purposes, it is important to know how option prices (values or premiums) react to their various components. Four key variables that impact option pricing are: (1) changing spot rates, (2) time to maturity, (3) changing volatility, and (4) changing interest differentials. The corresponding measures of sensitivity are:

1. Delta—The sensitivity of option premium to a small change in the spot exchange rate.

2. Theta—The sensitivity of option premium with respect to the time to expiration

3. Lambda—The sensitivity of option premium with respect to volatility.

4. Rho and Phi—The sensitivity of option premium with respect to the interest rate differentials.

Exhibit 30 describes how these sensitivity measures are interpreted.

EXHIBIT 30

Interpretations of Option Pricing Sensitivity Measures

| Sensitivity | ||

| Measures | Interpretation | Reasoning |

| Delta | The higher the delta, the greater the chance | Deltas of .7 or up are considered high. |

| of the option expiring in-the-money. | ||

| Theta | Premiums are relatively insensitive until the | Longer maturity options are more highly valued. |

| last 30 or so days. | This gives a trader the ability to alter an option | |

| position without incurring significant time value | ||

| deterioration. | ||

| Lambda | Premiums rise with increases in volatility. | Low volatility may cause options to sell. A trader |

| is hoping to buy back for a profit immediately | ||

| after volatility falls, causing option premiums to | ||

| drop. | ||

| Rho | Increases in home interest rates cause call | A trader is willing to buy a call option on foreign |

| option premiums to increase. | currency before the home interest rate rises | |

| (interest rate for the home currency), which will | ||

| allow the trader to buy the option before its price | ||

| increases. | ||

| Phi | Increases in foreign interest rates cause call | A trader is willing to sell a call option on foreign |

| option premiums to decrease. | currency before the foreign interest rate rises | |

| (interest rate for the foreign currency), which will | ||

| allow the trader to sell the option before its price | ||

| decreases. |

CURRENCY QUOTATIONS

Currency quotes are always given in pairs because a dealing bank usually does not know whether a prospective customer is in the market to buy or to sell a foreign currency. The first rate is the bid, or buy rate; the second is the sell, ask, or offer rate.

EXAMPLE 36

Suppose the pound sterling is quoted at $1.5918-29. This quote means that banks are willing to buy pounds at $l.5918 and sell them at $1.5929. Note that the banks will always buy low and sell high. In practice, however, they quote only the last two digits of the decimal. Thus, sterling would be quoted at 18-19 in this example.

Note that when American terms are converted to European terms or direct quotations are converted to indirect quotations, bid and ask quotes are reversed; that is, the reciprocal of the American (direct) bid becomes the European (indirect) ask and the reciprocal of the American (direct) ask becomes the European (indirect) bid.

EXAMPLE 37

So, in Example 1, the reciprocal of the American bid of $1.5918/£ becomes the European ask of £0.6282 and the reciprocal of the American ask of $1.5929/£ equals the European bid of £0.6278/$ resulting in a direct quote for the dollar in London of £0.6278-82. Exhibit 31 summarizes this result.

EXHIBIT 31

Direct Versus Indirect Currency Quotations

| Direct (American) | Indirect (European) |

| $1.5918-29 | £0.6278-82 |

CURRENCY REVALUATION

Also called appreciation or strengthening, revaluation of a currency refers to a rise in the value of a currency that is pegged to gold or to another currency. The opposite of revaluation is weakening, deteriorating, devaluation, or depreciation. Revaluation can be achieved by raising the supply of foreign currencies via restriction of imports and promotion of exports.

CURRENCY RISK

Also called foreign exchange risk, exchange rate risk, or exchange risk, currency risk is the risk that tomorrow’s exchange rate will differ from today’s rate. In financial activities involving two or more currencies, it reflects the risk that a change (gain or loss) in an entity’s economic value can occur as a result of a change in exchange rates. Currency risk applies to all types of multinational businesses—international trade contracts, international portfolio investments, and foreign direct investments (FDIs). Currency risk exists when the contract is written in terms of the foreign currency or denominated in foreign currency. Also, when you invest in a foreign market, the return on the foreign investment in terms of the U.S. dollar depends not only on the return on the foreign market in terms of local currency but also on the change in the exchange rate between the local currency and U.S. dollar.

The idea of exchange risk in trade contracts is illustrated in the following example.

EXAMPLE 38

Case I. An American automobile distributor agrees to buy a car from the manufacturer in Detroit. The distributor agrees to pay $25,000 upon delivery of the car, which is expected to be 30 days from today. The car is delivered on the thirtieth day and the distributor pays $25,000. Notice that, from the day this contract was written until the day the car was delivered, the buyer knew the exact dollar amount of his liability. There was, in other words, no uncertainty about the value of the contract.

Case II. An American automobile distributor enters into a contract with a British supplier to buy a car from the United Kingdom for 8,000 pounds. The amount is payable on the delivery of the car, 30 days from today. Suppose, the range of spot rates that we believe can occur on the date the contract is consummated is $2 to $2.10. On the thirtieth day, the American importer will pay some amount in the range of 8,000 x $2.00 = $16,000 to 8,000 x 2.10 = $16,800 for the car. As of today, the American firm is uncertain regarding its future dollar outflow 30 days hence. That is, the dollar value of the contract is uncertain.

These two examples help illustrate the idea of foreign exchange risk in international trade contracts. In the case of the domestic trade contract, given as Case I, the exact dollar amount of the future dollar payment is known today with certainty. In the case of the international trade contract given in Case II, where the contract is written in the foreign currency, the exact dollar amount of the contract is not known. The variability of the exchange rate induces variability in the future cash flow. This is the risk of exchange-rate changes, exchange risk, or currency risk. Currency risk exists when the contract is written in terms of the foreign currency or denominated in foreign currency. There is no exchange risk if the international trade contract is written in terms of the domestic currency. That is, in Case II, if the contract were written in dollars, the American importer would face no exchange risk. With the contract written in dollars, the British exporter would bear all the exchange risk, because the British exporter’s future pound receipts would be uncertain. That is, he would receive payment in dollars, which would have to be converted into pounds at an unknown (as of today) pound-dollar exchange rate. In international trade contracts of the type discussed here, at least one of the two parties bears the exchange risk. Certain types of international trade contracts are denominated in a third currency, different from either the importer’s or the exporter’s domestic currency. In Case II, the contract might have been denominated in the Deutsche mark. With a DM contract, both the importer and the exporter would be subject to exchange-rate risk.

Exchange risk is not limited to the two-party trade contracts; it exists also in foreign direct or portfolio investments. The next example illustrates how a change in the dollar affects the return on a foreign investment.

EXAMPLE 39

You purchased bonds of a Japanese firm paying 12% interest. You will earn that rate, assuming interest is paid in marks. What if you are paid in dollars? As Exhibit 32 shows, you must then convert yens to dollars before the payout has any value to you. Suppose that the dollar appreciated 10% against the yen during the year after purchase. (A currency appreciates when acquiring one of its units requires more units of a foreign currency.) In this example, 1 yen required 0.01 dollars, and later, 1 yen required only 0.0091 dollars; at the new exchange rate it would take 1.099 (0.01/0.0091) yens to acquire 0.01 dollars. Thus, the dollar has appreciated while the yen has depreciated. Now, your return realized in dollars is only 10.92%. The adverse movement in the foreign exchange rate—the dollar’s appreciation—reduced your actual yield.

EXHIBIT 32

Exchange Risk and Foreign Investment Yield

| Exchange Rate: | |||

| No. of Dollars | |||

| Transaction | Yens | per 1 Yen | Dollars |

| On 1/1/20X1 | |||

| Purchased one German bond | |||

| with a 12% coupon rate | 500 | $0.01* | $5.00 |

| On 12/31/20X1 | |||

| Expected interest received | 60 | 0.01 | 0.60 |

| Expected yield | 12% | 12% |

| On 12/31/20X1 | |||

| Actual interest received | 60 | 0.0091** | 0.546 |

| Realized yield | 12% | 10.92%*** |

* For illustrative purposes assume that the direct quote is $0.01 per yen. ** $0.01/(1 + .1) = $0.01/1.1 = $0.0091. *** $0.546/$5.00 = .1092 = 10.92%.

Note, however, that currency swings work both ways. A weak dollar would boost foreign returns of U.S. investors. Exhibit 33 is a quick reference to judge how currency swings affect your foreign returns.

EXHIBIT 33

Currency Changes vs. Foreign Returns in U.S. Dollars

| Change | in Foreign Currency against the Dollar Return | ||||

| Foreign | 20% | 10% | 0% | -10% | -20% |

| 20% | 44% | 32 | 20 | 8 | -4 |

| 10 | 32 | 21 | 10 | -1 | -12 |

| 0 | 20 | 10 | 0 | -10 | -20 |

| -10 | 8 | -1 | -10 | -19 | -28 |

| -20 | -4 | -12 | -20 | -28 | -36 |

CURRENCY RISK MANAGEMENT

Foreign exchange rate risk exists when the contract is written in terms of the foreign currency or denominated in the foreign currency. The exchange rate fluctuations increase the riskiness of the investment and incur cash losses. The financial manager must not only seek the highest return on temporary investments but must also be concerned about changing values of the currencies invested. You do not necessarily eliminate foreign exchange risk. You may only try to contain it. In countries where currency values are likely to drop, financial managers of the subsidiaries should:

• Avoid paying advances on purchase orders unless the seller pays interest on the advances sufficient to cover the loss of purchasing power.

• Not have excess idle cash. Excess cash can be used to buy inventory or other real assets.

• Buy materials and supplies on credit in the country in which the foreign subsidiary is operating, extending the final payment date as long as possible.

• Avoid giving excessive trade credit. If accounts receivable balances are outstanding for an extended time period, interest should be charged to absorb the loss in purchasing power.

• Borrow local currency funds when the interest rate charged does not exceed U.S. rates after taking into account expected devaluation in the foreign country.

A. Ways to Neutralize Foreign Exchange Risk

Foreign exchange risk can be neutralized or hedged by a change in the asset and liability position in the foreign currency. Here are some ways to control exchange risk.

A.1. Entering a Money-Market Hedge

Here the exposed position in a foreign currency is offset by borrowing or lending in the money market.

EXAMPLE 40

XYZ, an American importer enters into a contract with a British supplier to buy merchandise for 4,000 pounds. The amount is payable on the delivery of the good, 30 days from today. The company knows the exact amount of its pound liability in 30 days. However, it does not know the payable in dollars. Assume that the 30-day money-market rates for both lending and borrowing in the U.S. and U.K. are .5% and 1%, respectively. Assume further that today’s foreign exchange rate is $1.735 per pound.

In a money-market hedge, XYZ can take the following steps:

Step 1. Buy a one-month U.K. money-market security, worth 4,000/(1 + .005) = 3,980 pounds.

This investment will compound to exactly 4,000 pounds in one month. Step 2. Exchange dollars on today’s spot (cash) market to obtain the 3,980 pounds. The dollar amount needed today is 3,980 pounds x $1.7350 per pound = $6,905.30. Step 3. If XYZ does not have this amount, it can borrow it from the U.S. money market at the going rate of 1%. In 30 days XYZ will need to repay $6,905.30 x (1 + .1) = $7,595.83.

Note: XYZ need not wait for the future exchange rate to be available. On today’s date, the future dollar amount of the contract is known with certainty. The British supplier will receive 4,000 pounds, and the cost of XYZ to make the payment is $7,595.83.

A.2. Hedging by Purchasing Forward (or Futures) Exchange Contracts

A forward exchange contract is a commitment to buy or sell, at a specified future date, one currency for a specified amount of another currency (at a specified exchange rate). This can be a hedge against changes in exchange rates during a period of contract or exposure to risk from such changes. More specifically, do the following: (1) Buy foreign exchange forward contracts to cover payables denominated in a foreign currency and (2) sell foreign exchange forward contracts to cover receivables denominated in a foreign currency. This way, any gain or loss on the foreign receivables or payables due to changes in exchange rates is offset by the gain or loss on the forward exchange contract.

EXAMPLE 41

In the previous example, assume that the 30-day forward exchange rate is $1.6153. XYZ may take the following steps to cover its payable.

Step 1. Buy a forward contract today to purchase 4,000 pounds in 30 days. Step 2. On the 30th day pay the foreign exchange dealer 4,000 pounds x $1.6153 per pound = $6,461.20 and collect 4,000 pounds. Pay this amount to the British supplier.

Note: Using the forward contract XYZ knows the exact worth of the future payment in dollars ($6,461.20).

Note: The basic difference between futures contracts and forward contracts is that futures contracts are for specified amounts and maturities, whereas forward contracts are for any size and maturity.

A.3. Hedging by Foreign Currency Options

Foreign currency options can be purchased or sold in three different types of markets: (1) options on the physical currency, purchased on the over-the counter (interbank) market;

(2) options on the physical currency, purchased on organized exchanges such as the Philadelphia Stock Exchange and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange; and (3) options on futures contracts, purchased on the International Monetary Market (IMM) of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange.

A.4. Using Currency Swaps

Currency swaps are temporary exchanges of funds between two parties—central banks or the central bank and MNC—that do not go through the foreign exchange market. Suppose a U.S. MNC wants to inject capital into its Ghanan subsidiary. The U.S. company signs a swap contract with the central Ghanan bank, then deposits dollars at the bank. The bank then makes a loan in Ghanan currency to the subsidiary firm. At the end of the loan period, the subsidiary pays off the loan to the bank, which returns the original dollar deposit to the U.S. MNC. Usually, the central bank does not pay interest on the foreign currency deposit it receives but does charge interest on the loan it makes. Therefore, the cost of the swap includes two interest components: the interest on the loan and the foregone interest on the deposit. In recent years, MNCs have made direct swaps with each other. In the late 1970s some British and U.S. companies were swapping currency, typically for about 10 years. Because British interest rates were higher, the U.S. firm paid a 2% fee to the British firm. To protect against movements in U.S.-U.K. exchange rates, many swap contracts often had a top-off provision, calling for renegotiation at settlement time if the exchange rate moved over 10%.

A.5. Repositioning Cash by Leading and Lagging the Time at Which an MNC Makes

Operational or Financial Payments

Often, money- and forward-market hedges are not available to eliminate exchange risk. Under such circumstances, leading (accelerating) and lagging (decelerating) may be used to reduce risk.

A.6. Maintaining Balance between Receivables and Payables Denominated in a Foreign

Currency

MNCs typically set up multilateral netting centers as a special department to settle the outstanding balances of affiliates of an MNC with each other on a net basis. These act as a clearing house for payments by the firm’s affiliates. If there are amounts due among affiliates they are offset insofar as possible. The net amount would then be paid in the currency of the transaction; thus, a much lower quantity of the currency must be acquired.

A.7. Maintaining Monetary Balance

Monetary balance refers to minimizing accounting exposure. If a company has net positive exposure (more monetary assets than liabilities), it can use more financing from foreign monetary sources to balance things. MNCs with assets and liabilities in more than one foreign currency may try to reduce risk by balancing off exposure in the different countries. Often, the monetary balance is practiced across several countries simultaneously.

A.8. Positioning of Funds through Transfer Pricing

A transfer price is the price at which an MNC sells goods and services to its foreign affiliates or, alternatively, the price at which an affiliate sells to the parent. For example, a parent that wishes to transfer funds from an affiliate in a depreciating-currency country may charge a higher price on the goods and services sold to this affiliate by the parent or by affiliates from strong-currency countries. Transfer pricing affects not only transfer of funds from one entity to another but also the income taxes paid by both entities.

CURRENCY SPREAD

A currency spread involves buying an option at one strike price and selling a similar option at a different strike price. Thus, the currency spread limits the option holder’s downside risk on the currency bet but at the cost of limiting the position’s upside potential as well. There are two types of currency spreads:

• A bull spread, which is designed to bet on a currency’s appreciation, involves buying a call at one strike price and selling another call at a higher strike price.

• A bear spread, which is designed to bet on a currency’s decline, involves buying a put at one strike price and selling another put at a lower strike price.

CURRENCY SWAP

Currency swaps are temporary exchanges of monies between two parties that do not go through the foreign exchange market. In official swaps, the two parties are central banks. Private swaps are between central banks and MNCs. Currency swaps are often used to minimize currency risk.

CURRENCY TRANSLATION METHODS

Accountants are concerned with the appropriate way to translate foreign currency-denominated items on financial statements into their home currency values. If currency values change, translation gains or losses may result. A foreign currency asset or liability is said to be exposed if it must be translated at the current exchange rate. Regardless of the translation method selected, measuring accounting exposure is conceptually the same. It involves determining which foreign currency-denominated assets and liabilities will be translated at the current (postchange) exchange rate and which will be translated at the historical (prechange) exchange rate. The former items are considered to be exposed, while the latter items are regarded as not exposed. Translation exposure is the difference between exposed assets and exposed liabilities.

There are various alternatives available to measure translation (accounting) exposure. The basic translation methods are the current-rate method, current/noncurrent method, monetary/ nonmonetary method, and temporal method. The current-rate method treats all assets and liabilities as exposed. The current/noncurrent method treats only current assets and liabilities as being exposed. The monetary/nonmonetary method treats only monetary assets and liabilities as being exposed. The temporal method translates financial assets and all liabilities valued at current cost as exposed and historical cost assets and liabilities as unexposed. Exhibit 33 summarizes these four currency translation methods.

EXHIBIT 34

Four Currency Translation Methods

| Items Translated at | ||

| Current Rate | Historical Rate | |

| Current rate | All assets and all liabilities and | — |

| common stock | ||

| Current/noncurrent | Current assets and current | Fixed assets and long-term liabilities |

| liabilities | Common stock | |

| Monetary/nonmonetary | Monetary assets and all liabilities | Physical assets |

| Common stock | ||

| Temporal | Financial assets and all liabilities | Physical assets valued at historical |

| and physical assets valued at | cost | |

| current price | Common stock | |

EXAMPLE 42

G&G France, the French subsidiary of a U.S. company, G&G, Inc., has the following balance sheet expressed in French francs: