INTRODUCTION

The vast majority of today’s teachers were never taught using computers. They have no firsthand experience using computers for teaching and learning and they may even believe computers are a threat to their jobs. Helping these teachers to become effective online teachers requires a systematic multi-layered approach to professional development. First, teachers have to be convinced of their institution’s commitment to online instruction. Then, they need support and guidance as they move through various levels of understanding and concern about what online learning is and its role and value in education. Finally, teachers need to develop competencies that will enable them to be successful online teachers. This chapter presents a brief background on the use of technology in education, research on approaches to professional development, and specific information on the competencies required to be an effective online teacher.

BACKGROUND: TECHNOLOGY AND TEACHING

Even in the world’s most advanced schools, computers have only been available for a few decades. During that time, huge advances have been made in the technologies available for use in schools, their educational applications, and our understanding of how to use them to promote learning.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, as computers were just beginning to appear in classrooms, professional development focused on operating the computer and running software packages. This included basic operation and maintenance, programming, using productivity tools (e.g., word processors, databases, and spreadsheets) and eventually the use of grade-level appropriate curriculum-specific instructional programs.

By the late 1980s professional development had changed its focus. No longer was the goal to simply make teachers competent users. Rather, it was to help them develop strategies to increase the effective student use of technology for learning. Teachers were exposed to concepts such as the use of collaborative learning in technology-based learning environments. They also began requiring students to use technology for research, data collection, and presentation of findings. Teachers’ roles shifted from using technology to teach, to using technology to facilitate learning.

The introduction of the Internet and online resources in the late 1990s presented another change in the use of technology in education. Teachers and students began to browse this virtual library for information and resources heretofore unavailable to them. Computers became a tool for searching, retrieving, manipulating, and sharing information. Teachers began to see the online environment as an information repository that contributed to student learning and through which students could contribute to the learning of others. Teaching strategies began to make use of this rich resource by including online research and reporting activities.

By the early 2000s, use of the Internet for communication had evolved beyond mere text messages to include a full range of media — images, audio, and video. Online distance education began to gain popularity. All levels of education began to see online learning as a vehicle for expanding the reach of institutions and by offering educational services to potential students they could not previously reach. The concept of online education presented yet another opportunity to change the role of teachers. The personal relationship between teachers and students, which was so often a critical component of classroom instruction, took on an entirely different character. Online distance education courses created instructional environments where teachers and students interacted in a digital world and where they might never meet, speak, or even see each other in person.

Overview

Online distance education (also commonly referred to as distance education, online learning, online teaching, and distributed learning), as the name implies, delivers instruction using a computer network, without requiring face-to-face meetings of students and faculty (Arabasz & Baker, 2003). These online courses, taught in virtual classrooms, are often facilitated by use of the Internet (Spector & de la Tega, 2001), and may be synchronous, asynchronous, or a combination thereof.

Online distance education offers exciting opportunities for learners, teachers, and educational institutions. Internet technology allows distance education to make efficient, content-rich, interactive learning opportunities available to learners at locations and in ways previously not possible. For an increasing number of institutions, this capability is broadening and extending their methods of delivering education. Consequently, online distance education has been the focus of numerous research studies, position papers, standards documents, and guidelines. These documents (e.g., Sales, 2005; Smith, 2005; The Institute for Higher Education,April, 2000; The Higher Education Program, and Policy Council of the American Federation of Teachers, May, 2000; Twigg, 2003a, 2003b), address the relative instructional effectiveness of online learning, educational quality, student needs, institutional support, instructional strategies, costs, required teacher competency, and more.

One report, Quality On the Line (The Institute for Higher Education, 2000), studied six institutions actively involved in online education and constructed a list of 24 “benchmarks that are essential for quality Internet-based distance education” (p.25). These benchmarks represented seven categories:

1. Institutional Support

2. Course Development

3. Teaching/Learning

4. Course Structure

5. Student Support

6. Faculty Support

7. Evaluation and Assessment

Across all levels of instruction, responsibility for achieving these benchmarks is shared by institutions, teachers and their program areas, and students. However, teachers are primarily involved in the Course Development, Teaching/Learning, Course Structure, and Faculty Support benchmarks.

MAIN FOCUS: A MODEL FOR PREPARING TEACHERS TO TEACH ONLINE

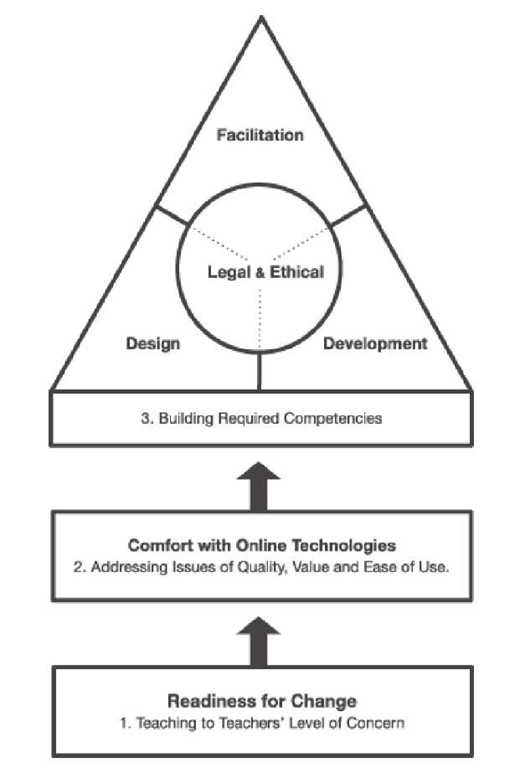

Preparing teachers to participate effectively in online instruction (e.g., Course Development, Teaching/Learning, Course Structure, and Faculty Support) requires carefully structuring professional development. The model below (Figure 1) illustrates the critical components such preparation should address.

Functioning both as a model and a hierarchy, Figure 1 suggests online teacher training begin by assessing and addressing teachers’ readiness to change as indicated through their expressions of concern about the impact of online teaching and learning. It then moves into increasing their comfort level with online technologies as they relate to quality of instruction, correlation of online instruction with the values of the institution, and the ease with which they can teach using online instruction. Only after these issues have been addressed should teacher preparation focus on developing their competencies to teach online.

Figure 1. Preparing teachers to teach online

The remainder of this chapter is devoted to explaining and supporting the elements of this model and the progression it suggests.

Readiness for Change: A Concerns-Based Approach

For many teachers the transition from teaching in a classroom, where they have direct and personal contact with all of their students, to online teaching, where interactions are often restricted to a virtual environment, is a significant change. The process of change often involves exposing teachers to and integrating them in a number of technology-based teaching and learning activities. The goal is to increase their knowledge, skill, and confidence in the use of educational technology over time.

The level of teacher readiness for online distance education training should be assessed prior to integrating teachers into any formal training experiences. Loucks-Horsley (1996), while studying teacher acceptance of change in science curricula, proposed that teacher readiness for change can be determined by the types of questions or concerns they express about the change or innovation being considered. This concerns-based approach identifies a seven-level hierarchy of teacher readiness (see Table 1).

Teacher concerns move from the lowest level, Awareness, upward. At the lowest stages, stages 0 through 2, the teacher is moving through levels of considering the innovation as a teaching tool. During stages 3 and 4 the teacher’s energy is focused on using and refining use of the tool to optimize teaching and learning experiences. The highest two stages, 5 and 6, show teachers moving into the creative realm that extends the innovation further into unanticipated or developed areas. Naturally, different teachers will move through the hierarchy at different rates and many may never reach the upper levels.

Training should be geared to the level of readiness being expressed by a teacher. In a recent project in Oman, Sales (2007) reports seeing teachers express concerns from the lowest levels to the highest. Some teachers, although asked to participate in a pilot of online teacher training, simply chose to ignore the opportunity (Stage 0). Others expressed their concerns by asking questions about the project’s purpose and the amount of time they would need to commit to it (Stages 1 and 2). Even further up the hierarchy, teachers expressed concern about the time it was taking away from other instructional approaches and possible effects on students (Stages 3 and 4). Within Oman’s Ministry of Education some of the trainers participating in the project began suggesting modifications and adaptation of the online learning to better reach learners and achieve desired outcomes (Stage 6).

In some situations the full spectrum of concerns may be represented within the population to be trained. In these cases a series of training interventions will likely be required to reach teachers at different levels of concern. Institutions, having limited resources for the integration of an innovation, may need to make decisions about their ability to provide training to teachers at every level.

Characteristics Influencing Adoption of Technologies

There are many political, cultural, economic, ethical, and resource issues that impact teacher ability to prepare for and use online distance education. For example, Sales and Emesiochl (2004) report on a civil service retirement act in the Republic of Palau which forced technology-trained teachers into retirement and flooded schools with untrained teachers. Sales (2007) also reports how a number of teachers in the Sultanate of Oman resisted the adoption of online training because they felt it required them to participate in training on their own time, rather than being released from their teaching responsibilities, as they historically have been, to participate in face-to-face training.

Table 1. Typical expressions of concern about an innovation

|

Stages of Concern |

Expression of Concern |

|

6. Refocusing |

I have some ideas about something that would work even better. |

|

5. Collaboration |

How can I relate what I am doing to what others are doing? |

|

4. Consequence |

How is my use affecting learners? How can I refine it to have more impact? |

|

3. Management |

I seem to be spending all my time getting materials ready. |

|

2. Personal |

How will using it affect me? |

|

1. Informational |

I would like to know more about it. |

|

0. Awareness |

I am not concerned about it. |

Further, an individual’s level of readiness as reflected in the concern-based approach (Loucks-Horsley, 1996) to teacher development discussed above, is strongly influenced by his or her personal beliefs as well as the environment in which he or she lives and works. Teachers’ perceptions of a specific educational technology and their beliefs about their own ability to use it easily, successfully, and with better results, strongly influence their willingness to consider adoption of that technology.

In their chapter on the adoption of learning technologies, Wilson, Sherry, Dobrovolny, Batty and Ryder (2001), argue in support of the validity of the STORC approach when applied to technology interventions in education. STORC is an acronym for a set of characteristics considered during adoption of innovations. These characteristics represent attributes or conditions that must be evaluated favorably before an innovation has sufficient appeal to reach a given level of adoption. In addition to the original set of characteristics (simplicity, trialability, observability, relative advantage, and compatibility), Wilson, et. al. (2001) proposed a condition of support be added, thereby changing the acronym to STORCS (see Table 2).

The categories of characteristics in this approach may be independent of each other, or may have an influence on each other. However, they do not have a hierarchical or ordinal relationship. Rather, the point Wilson and his co-authors make in their presentation of this approach is that the more characteristics present, the greater the likelihood an innovation will be successfully adopted.

Professional development programs must consider teacher responses to each of the question types listed in the STORCS approach. Training interventions should help teachers understand and generate thoughtful and positive answers to these questions. Their affirmation of these questions will significantly influence their approach to, and enthusiasm for, online teaching.

Instructional Design

The EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research (ECAR) recently sponsored a study to examine the e-learning activities in higher education entitled, Evolving Campus Support ModelsforE-Learning Courses. In a summary of the report’s findings, Arabasz and Baker (2003) identified major concerns of online teachers related to distance education.

The first concern cited was “lack of knowledge to design courses with technology” (p.4). This concern is supported by Siragusa (2000). He argues that online teachers who do not possess the necessary skills in instructional design are increasingly being encouraged to develop online courses. He states:

Table 2. An adaptation of the extended STORC approach to adoption of an innovation

|

Category |

Characteristic |

|

|

S |

Simplicity |

Is the innovation easy to understand, maintain, and use? Can it be easily explained to others? |

|

T |

Trialability |

Can the innovation be tried out on a limited basis? Can the decision to adopt be revised? |

|

O |

Observability |

Are the results of the innovation visible to others, so that they can see how it works and observe the consequences? |

|

R |

Relative Advantage |

Is the innovation seen as better than that which it replaces? Is the innovation more economical, more socially prestigious, more convenient, and/or more satisfying? |

|

C |

Compatibility |

Is the innovation consistent with the values, past experience, and needs of the potential adopters? |

|

S |

Support |

Is there enough support to do this? Is there enough time, energy, money, and resources to ensure the project’s success? Is there also administrative and political support for the project? |

Instructional design decisions that lead to the way in which students learn on the Internet are being placed in the hands of lecturers who are only just coming to grips with online learning and the use of the Internet. … Research and development for online learning has notyet caught up with the pace at which courses are appearing on the Internet. Instructional design principles that were developed for computer-assisted instruction appear to be overlooked by those now developing materials for the Internet. (p.1)

Instructional design is the process of planning for the development and delivery of effective education and training materials. Instructional designers use a variety of models that ensure a careful and systematic process is employed. Effective processes begin with a needs assessment and continue on to examine content/learning requirements, learner needs, the learning environments, delivery systems, tools and resources available for development and delivery, as well as other resources and constraints that will impact the project (e.g. financial resources, time available for the project, talents and experiences of those working on the project, social or political pressures). This information is then used to develop learning outcomes, select instructional strategies and techniques, guide the selection of instructional resources, and development of course content.

When applied in distance education, or other forms of course development, instructional design results in carefully structured and thoroughly documented plans for the production of the online course materials. These plans provide an opportunity to carefully review content, sequence methods and assessment to ensure the most instructionally sound course is being developed. This documentation also serves as an excellent resource when conducting maintenance evaluations or implementing revisions to the course structure, content, or function.

Concerns are expressed among online teachers and distance education scholars regarding the preparation of teachers to create courses for the online environment. These concerns highlight the need for professional development programs that emphasize the creation of instructional design competencies among those responsible for course production.

Facilitation

Another significant concern of online teachers identified by Arabasz and Baker (2003) was “a lack of confidence in use of technology in teaching” (p.4). This concern is well founded given that online instruction requires teachers to use a variety of tools and techniques which are new to them. One of the recognized keys to the success of online courses is the facilitation of learning by online teachers (Jaques & Salmon, 2006; Salmon, 2000, 2002). This involves online communication with students and the creation online learning environments that require or encourage communications between students.

Stamper and Sales (2001) state that through frequent, timely, and personal communications with online students, teachers create the perception that they are close at hand — a “close apparent” distance. They argue this communication-enhanced relationship helps distance learners feel they are recognized, contributing members of the course. Stamper and Sales go on to suggest that by creating a close, apparent distance, instructors can increase learner satisfaction with online courses and reduce drop-out rates.

Salmon (2000, 2002) has conducted action research and published on the facilitation of online courses. Her work illustrates to teachers what she believes are critical skills and techniques specific to facilitating online courses. Through effective use of the e-moderating and e-activities behaviors she promotes, Salmon believes online learning opportunities can be optimized.

Facilitation skills are essential competencies to be included in online teacher development. Training should include modeling of techniques that increase communications. Teachers should be encouraged to plan frequent communications and to promptly address specific student needs.

Development

Course development is the actual production of the software version of a course for online delivery and the supporting instructional materials. Where a learning content management system (LCMS) is being used, online course development is likely to involve teachers in populating content presentation templates with text, graphics, photographs, and other instructional resources. Of course, working with the template interface and different media assets that need to be in the appropriate digital formats can be technically demanding. Since most teachers are not software geeks, this often presents a challenge to be addressed through support services or as part of the professional development program.

In the commercial e-learning development world, course production is a team process (Sales, 2002). Subject matter experts work with instructional designers, programmers and Web-developers, graphic artists, animators, database specialists, and media production professionals. Through a collaborative and iterative process, the instructional design is transformed into a functioning online course presentation, complete with management, record-keeping, and administrative features.

Some efforts to use a team approach have been undertaken in higher education (Wells, Warner & Steele, 1999).Anne Arundel Community College, for example, created an Online Academy to help instructors develop skills needed to prepare and deliver online courses. Even in this effort, however, online teachers are still expected to develop the course “using software he or she is comfortable working with.”

Most institutions expect online teachers to acquire the skills needed to develop and maintain their courses. Arabasz and Baker (2003) report that across all levels of higher education institutions, only 8% of institutional effort directed at online learning is spent on creating e-learning course elements. Instead of investing in course development, institutes are devoting resources to such areas as Web-based development tools, online references and resources, listservs, and help desks.

Each professional development program for online teachers needs to determine its own institutional competency requirements based on the unique combination of delivery system components and support options. At a minimum, teachers need to have a thorough understanding of development options and the vocabulary necessary to communicate with other members of the development team.

FUTURE TRENDS

Legal and Ethical Issues

Numerous legal and ethical issues are associated with online distance education. Copyright law, which has special interpretation when it comes to online courses (Hoffman, 2000), is often seen as the only legal issue of concern. However, Ko and Rossen (2001) in their book on online teaching identify a range of issues including copyright, acceptable use, plagiarism, and ownership of the newly created course materials. Mpofu (2002) provides a more comprehensive list by including discussions of privacy and licensing/piracy.

Professional development for online teachers must examine all relevant legal and ethical issues. Issues such as copyright and ownership need to be considered from the perspective of how they will influence design decisions. Acceptable use and plagiarism should be covered as they relate to informing students of institutional policies, posting information online for others to access, and evaluating student work. Issues or software licensing and piracy may influence decisions related to development and delivery environments as well as assignments given to students. Finally, the legal and ethical issues associated with data privacy in terms of students’ records and personal safety should also be addressed.

CONCLUSION

Professional development to prepare teachers for online distance education must accommodate the unique needs of each individual teacher. Teacher concerns, readiness to adopt new technologies, and an institution’s specific policies, systems, and support services all contribute to the need for individualized or custom tailored training experiences.

Institutions and trainers must recognize that development of online teachers requires an on-going process, not a single event. Professional development programs need to offer a series of graduated experiences that move teachers along a continuum. Taking them from an entry point based on each teacher’s unique needs to an exit point based on institutional competency standards.

Professional development programs should engage teachers in activities that move them from their current level of understanding in each of the follow domains.

• Readiness for Change: Teacher readiness for change can be determined by the types of questions or concerns they express about the change or innovation being considered.

• Comfort with Online Technologies: Teachers’ beliefs about their own ability to use it easily, successfully, and with better results strongly influence their willingness to consider adoption of that technology

• Design: Analysis, instructional design, creative design, and in some cases interface design. This domain encompasses the skills and processes necessary to take a course from the concept stage to the point where it is ready for production.

• Development: Creation of the media assets that support the content (produced during the design phase), production of the software product (through programming or the use of a tool), and quality assurance testing. The development domain begins with the design and ends with a fully functional, error free, course.

• Facilitation: Instructor skills and behaviors, and strategies and techniques for course delivery. Facilitation involves taking the completed course and creating a dynamic learning experience for students. This domain involves teachers in presenting content, engaging students, providing feedback, and otherwise creating a positive learning environment online in support of the “automated” portion of the course.

• Legal and Ethical Issues: Laws, rules, regulations, policies, procedures, and associated consequences. This domain, as shown in the Competency Model, overlaps the other three domains. Legal and ethical competencies influence teachers’ execution of competencies in each of the other domains.

KEY TERMS

Apparent Distance: The perceived proximity of faculty and students in a distance education environment. Close apparent distance is the term used to describe a relationship that is perceived as positive, supporting, in regular communication – a relationship in which the student and faculty are well known to each other and where communications flow easily.

Competency: A statement that defines the qualification required to perform an activity or to complete a task. Faculty competencies for online distance education identify the qualifications needed to be successful in this job.

Course Development: The actual production of the software version of a course for online delivery and the supporting instructional materials. Faculty involved in the development of online courses are often required to have technology specific knowledge and skills – digitizing, converting file formats, operation of specific software programs, and programming.

Fair Use: A term defined in the United States copyright act. It states the exemption for schools to some copyright regulations. (This exemption pre-dates many current educational applications oftechnology and may be not address some online learning situations.)

Instructional Design: The process of planning for the development and delivery of effective education and training materials. Instructional designers employ a systematic process that considers learner needs, desired learning outcomes, delivery requirements and constraints, motivation, psychology, and related issues.

Online Teaching: Delivers instruction using a computer network, usually the Internet, without requiring face-to-face meetings of students and faculty. Courses may be synchronous, asynchronous, or a combination. (also commonly referred to as online distance education, distance education, online learning, and distributed learning)

Data Privacy: Current United States laws provide protection to private data, including students’ performance data. Online distance education environments need to address privacy issues though design of courses and security features built into record keeping systems.

Piracy: Refers to the illegal or unlicensed use of software.