Fertility rates that had remained fairly stable through the sixteenth to the end of the eighteenth centuries in Europe and in what was to become the United States began to drop in the nineteenth century. Although the drop in family size could be partly explained by lengthy periods of continence and extended periods of breast-feeding, that women stopped giving birth at much earlier ages than in the past indicates that some sort of family planning was involved. The fertility rate in the United States, for example, dropped 50 percent between 1800 and 1900. The decline in the fertility rate was first noticeable in France at the end of the eighteenth century, and it was slower to appear in the rest of Europe, but it gradually did so.

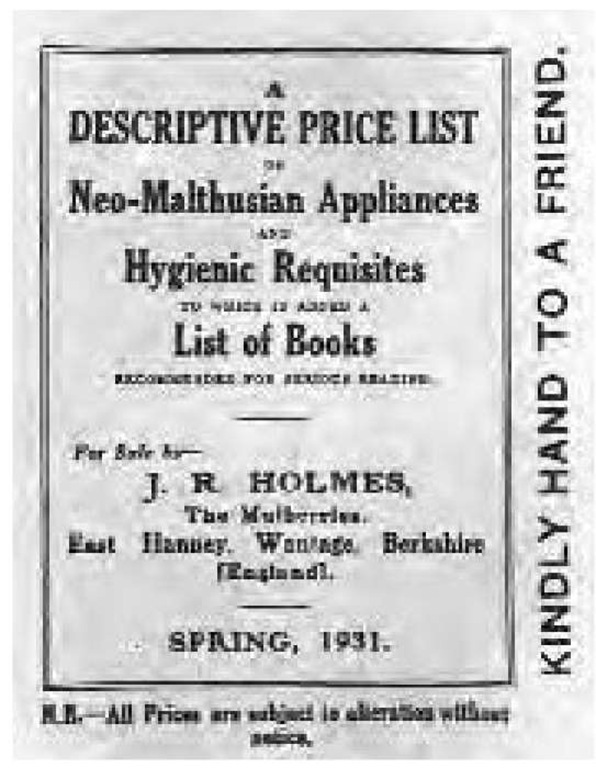

The neo-Malthusians published booklets describing contraceptive techniques, as the cover of this 1931 booklet demonstrates.

Some have explained this through what is called an adjustment theory, that is, the number of births per family went down because of changes in living conditions. One such change is hypothesized to be a decline in the rate of infant mortality. Even if this was a factor, it does not explain why the decline in the French birthrate began in the eighteenth century and why even in industrializing countries, such as England and Belgium, marital fertility fell before infant mortality figures declined.

On the other hand are those who are called the innovations theorists. They have been more interested in what men and women thought than in census tables indicating what they did. An individual who believed in the possibility of controlling nature would, it has been argued, be more likely to limit family size than the one who felt powerless and alienated. As evidence for this, the innovations theorists point out that those most likely to be the first users of birth control would be the self-confident, future-oriented individuals in society. According to this theory, the impetus would come from the enlightened upper classes, and then a generation or so later they would be followed by other groups as middle-class mores were diffused.

Unfortunately, there are holes in the theory when the actual historical data are examined. In France, for example, limitation of family size took place among the peasant classes in the eighteenth century. Such a decline in birthrate has been attributed to the peasant’s desire to avoid dividing land among heirs. A similar decline in birthrate among the bourgeoisie has been explained as an effort to maintain a more comfortable lifestyle. Other explanations have been offered for other countries and subgroups, but that it happened might indicate what J. A. Banks and others have called a cultural innovation. Those who first restricted births did not do so to escape poverty, but to protect new-found prosperity, in effect carrying out a revolution of rising expectations. The result was a kind of trickle-down theory in which the lead of the upper classes would be followed by the lower classes as they too began to anticipate that a change for the better might be in store for them. Also important was the growing urbanization, which meant greater mobility and also greater secularization. Traditional family ties were weakened and the influence of the traditional village attitudes diminished. Inevitably urban family size declined before rural but it is also true that the economic value of children as workers declined and they increasingly had less value in the urban setting than they did in a rural one, where the family farm could not function without the whole family being involved in production.

As McLaren has pointed out, even though such suppositions are true and all classes and ethnic groups ultimately saw the wisdom of adopting the small family model, they might well have had different reasons.Women and men view fertility controls differently, so does the church, the medical profession, and even the state. Did people in the past want the large number of births that occurred? There was, as the various entries in this topic indicate, always among women some interest in various means of preventing pregnancy or achieving an abortion. Although the methods used were not necessarily effective, some were far more effective than others. Many, if not most, women who wanted to avoid pregnancy tried some of the contraceptive formulas and then, if they did not work, and if the fall back on abortion did not work either, they accepted the inevitable. Infanticide and abandonment would be a final out.

At the end of the eighteenth century, while individuals such as the Marquis de Condorcet (1743-1794) wrote of the need to constrain population, the person who made population control seem to be a critical necessity was Thomas Malthus. The pessimistic Malthus emphasized that poverty could not be eliminated by charitable acts or individuals, but was a problem caused by the poor and which they would have to address themselves. He saw only misery for them unless they could keep their family size down by abstinence.The nineteenth-century British reformers who took up the cause of improving the lot of the poor, and who accepted Malthus’s ideas about the problems of population growth, wanted to intervene more positively and turned to advocating various methods of family planning. Even before Malthus had written, Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) had declared that population could be controlled by using such devices as a sponge, and it was the Bentham example that the reformers followed.

Certainly the reformers were motivated to try to alleviate the growing misery and hunger, which Malthus and predicted would occur, and the answer to them was also to educate the poor, who might previously not have known about birth control. These reformers are known collectively as the Neo-Malthusians because, although they accepted Malthus’s predictions, they did not accept his solution. Francis Place began the movement by distributing handbills in 1823 describing the use of the sponge; and in at least one version of his handbill, coitus interrup-tus. After this initial effort, Place turned to other things but his efforts were continued by his disciples, most notably Richard Carlile.

The Neo-Malthusian movement in the United States was not far behind. It was initiated by Robert Dale Owen and Charles Knowlton, each of whom had been influenced by Place and Carlile. Owen believed that Carlile was wrong in advocating partial withdrawal (he was) and instead advocated complete withdrawal, or coitus interruptus. He had little use for Carlile’s other contraceptive advice as well because Owen believed that the sponge was not particularly effective and that it was disagreeable, whereas the condom was inconvenient.

Knowlton’s discussion is far more comprehensive, and Norman Himes called it the most important account on the topic since Soranos wrote in the classical period.This is somewhat of an exaggeration because Knowlton primarily espoused douching. He is, however, important historically for the difficulties he had in disseminating his information, including some time in jail; his role in popularizing the cause; and for his book, which was widely known at the time of his death.

Probably the most influential of the early books was that by George Drysdale, whose initial book on sex education, The Elements of Social Science, was published anonymously in 1854. He devoted five and a half pages to ways of preventing conception, recommending the use of a sponge and then after intercourse a clear water douche. He disapproved of coitus interruptus because it might lead to mental and physical illness, and he believed that the condom was unaesthetic, dulled enjoyment, and might even produce impotence. He also considered the so-called safe period and believed that, although it was not infallible, it might reduce the likelihood of pregnancy.

All the early public advocates of contraceptives were political radicals and mostly free-thinkers.They believed they not only had a mission to serve the poor but also to challenge the moral and religious hypocrisy of the time. This made them suspect to most of the political establishment. George Drysdale, for example, worked closely with Charles Bradlaugh, an outspoken advocate of freethinking. In his newspaper, the National Reformer, which was founded in 1860, Bradlaugh attacked British social, religious, and sexual prejudices, declaring himself a republican, an atheist, and a Malthusian. Drys-dale contributed regularly to the newspaper, and his message about birth control as well as the book by Charles Knowlton on the subject were regularly printed in England.

In 1876, Henry Cook a Bristol bookseller, was sentenced to two years at hard labor for publishing an edition of Knowlton’s book, and the prosecution claimed that the book was adorned with “obscene” illustrations, probably illustrations of the male and female genitals. Knowlton’s book had been published in London without interference for some forty-three years by a number of booksellers, including Charles Watts (1836-1901). After the successful Bristol prosecution, Watts, to avoid jail himself, pleaded guilty to publishing an obscene book and was given a suspended sentence and cost provided he did not do so again.

As indicated elsewhere, this led to the Brad-laugh-Besant trial, which among other things gave widespread publicity to the birth control movement. Annie Besant, unimpressed by the advice in the Knowlton book, wrote The Law of Population, the first book by a woman on the subject. Her advice was judicious and accurate. She said the safe period was uncertain, coitus inter-ruptus was all right but she was not enthusiastic about it, douching with a solution of sulfate of zinc or of alum might work but it was up to the individual’s preference, the condom was acceptable as a guard against disease and might also be used as a contraceptive, but the sponge was the most desirable.

In the aftermath of the trial, the Malthusian League, which had been formed by Drysdale in the 1860s, was reinvigorated and reorganized and George Drysdale’s brother, Charles R. Drysdale, became its president. He was succeeded as president by Dr. Alice Vickery, his wife, emphasizing again the entrance of women into the movement. The league continued to publish the Malthusian until 1921, when it changed its name to the New Generation. It changed it back to the Malthusian in 1949 and ceased publication in 1952. In spite of the attention given to it by historians, the membership of the Malthusian League was never very large, usually less than one hundred active members, although the circulation of the journal was larger. Most of the league’s arguments were concentrated on economic and social arguments for family limitation. It did not publish a leaflet giving practical details of contraceptive techniques until 1913.

In the United States, the birth control movement ran into difficulty with the passage of the Comstock Act, which had devastating effects, and people such as Edward Bliss Foote, whose books and pamphlets on the subject of birth control were widely read, had to turn to other methods than books and pamphlets to reach an audience. It was not until the second decade of the twentieth century that the birth control movement could form anew.