The rise of Protestantism in the sixteenth century divided western Christianity into two opposing camps. Although Protestants went their separate ways, Catholic Europe developed what might be called a two-prong attack to counter the Protestant threat.The first was to make several internal reforms, many of which had been urged for centuries. For this purpose an ecumenical council was convened by Pope Paul III in 1545 in the northern Italian city of Trento. Known as the Council of Trent, it met, with several breaks, over the next 18 years. The second prong was what might be called the Catholic Reformation, an effort to oppose Protestants both intellectually and institutionally, but also politically and militarily. The military result was a series of wars in which the Catholics for more than one hundred years tried to destroy Protestantism and vice versa until politically the two sides arrived at an uneasy truce, dividing up Europe. Intellectually and institutionally in Catholic Europe the Catholic Reformation resulted in the reorganization and reinvigoration of the Inquisition; the promulgation of an Index of Prohibited Books; the formation of new religious orders, the most important of which was the Society of Jesus, or the Jesuits; and efforts to convert areas of Protestantism back to Catholicism and to proselytize the recently discovered areas of the world.

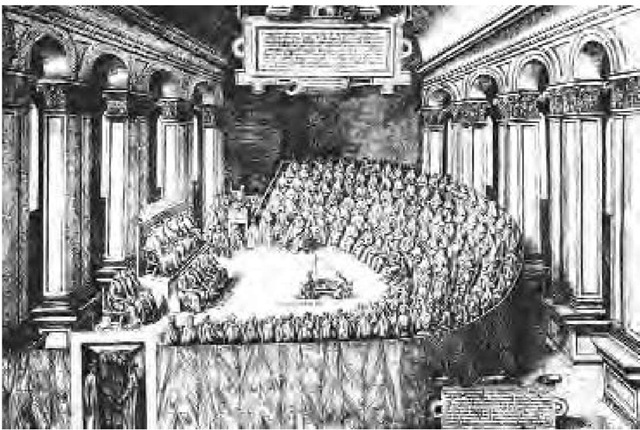

The Council of Trent, shown at work in this engraving, codified Roman Catholic positions on sex and marriage, including the prohibition of birth control.

The Council of Trent also debated issues of marriage and sex and finally codified them in the decree Tametsi, issued in 1563. The Tametsi and other Tridentine decrees were incorporated into the Roman Catechism issued in 1566 and this was followed by commentaries and elaborations. The most influential of these in terms of contraception was The Holy Sacrament of Marriage by the Spanish Jesuit Thomas Sanchez (1550—1610). In his extensive discussions of sexual enjoyment, he deals with fondling, fantasies, fellatio, and fore-play and ultimately regards them to be minor sins, or perhaps not even that, as long as they were a prelude to “natural intercourse,” with the man on top and no barriers to contraception. Not all commentators agreed with him, and there were fierce debates. Finally in 1679, Pope Innocent XI settled the matter by holding that Catholics should not engaged in any marital act simply for pleasure alone.Though such a condemnation sounds definitive, matters were not so simple, and John T. Noonan, a canon law expert, has claimed that the meaning of the pope was to use caution and prudence in teaching such beliefs.

The Catholic Church, however, continued to hold that refusal to engage in intercourse with one’s spouse was a mortal sin and mutual continence was permitted and even encouraged, especially if there already had been an abundance of offspring. Some authorities went so far as to argue that one spouse alone might refuse intercourse if he or she believed it was not possible to feed more offspring or that another child might be deemed a danger or detriment to offspring already born. This concept allowed some church authorities to emphasize that it was not only the production of children that was the goal of marriage, but that it was also important if not essential to take into account the good of the offspring.

Theologians were occasionally specific in discussing various means of contraception but usually preferred generalities instead of details. Obviously for a couple to begin an act of coitus but to withdraw without ejaculation in the vagina is a conscious effort to avoid procreation. But there were distinctions made. If ejaculation follows the withdrawal, the act is coitus inter-ruptus and was described by Catholic moralists as a sin against nature. If ejaculation after withdrawal is inhibited, the act is sometimes described as coitus reservatus or amplexus reservatus and this was treated differently by Catholic theological and legal authorities and even approved by some. It should be added, however, that modern sexologists distinguish between the two terms and coitus reservatus does not usually imply that the penis is withdrawn from the vagina. Rather it means only that motion ceases before orgasm, and after the orgasmic “crisis” diminishes, the couple can begin movement again. Amplexus coitus was generally regarded as tolerable, providing neither partner had an orgasm, but some held that amplex coitus was acceptable only if it could not involve penetration.

The use of anaphrodisiacs, substances believed to decrease libido or sexual function, were permitted and even praised, although not discussed as a means of contraception and never in any specific detail. In fact, Catholic theologians in general were careful to avoid discussion of herbal contraceptives and abortifacients, although they knew about them and some called them “poisons of sterility.” As far as any further description was concerned, the theologians observed the rule that silence was the best policy. Still, the discussion of anaphrodisiacs and amplexus reservatus implies a lessening of the Augustinian view that intercourse may be initiated only for procreation and shows a glimmer of recognition that there might well be other purposes.

One male contraceptive practice casually mentioned by one authority is a method originally described by Aristotle that involved “oiling” of the genitals with a “certain unguent which would induce sterility,” but what this unguent was and whether the sterility caused was permanent or temporary is not known. It has been hypothesized that the unguent might be cedar gum, and, if so, the effect would be temporary.

In general, however, the Catholic position looked askance at contraceptive information and in the new age of printing made efforts to prevent the dissemination of information about it.There was also potentially some loopholes for those couples using some form of birth control. Noonan claimed that in the post-Tridentine church good faith was to be protected in the confessional, and the confessor should not disturb the penitent ignorantly violating natural law and unlikely to amend his or her ways. Also there were some additional loopholes for women in the confessional because it was generally agreed that a woman, who in obedience to her husband engaged in coitus interruptus with him, was not guilty of a sin. Interpretation of this was usually left up to the confessor and some were more lenient than others.