A-Group culture

The A-Group is a distinctive culture of Lower Nubia contemporary with the Predynastic (Nagada) culture of Upper Egypt. This culture was first identified by George Reisner, who studied the artifacts collected during the First Archaeological Survey of Nubia (1907-8). Reisner’s classification was later revised by Trigger, Adams and Nordstrom, based on archaeological evidence from the UNESCO salvage campaign in Nubia (195965).

A-Group sites have been recorded throughout Lower Nubia (between the First and Second Cataracts). A few sites are known in the Batn el-Hajar region, and near Seddenga in the Abri-Delgo reach (south of the Second Cataract). Recently an A-Group site was discovered at Kerma, near the Third Cataract. A-Group sites include both settlements and cemeteries.

Diagnostic elements of this culture are pottery and graves. The pottery includes several different types of vessels. Black-topped pots, with a polished red slip exterior and a black interior and rim, are common. These pots, though similar to those of the Nagada culture in Upper Egypt, were locally manufactured. Pots with a painted geometric decoration, sometimes imitating basketwork, are particularly distinctive of this culture.

A-Group graves include mainly simple oval pits, and oval pits with a chamber on one side. There is no clear evidence of grave superstructures. At a single site, Tunqala West, tumuli with an offering place of stone and an uninscribed grave stela were recorded.

In A-Group burials, the bodies were laid in a contracted position on the right side, usually with the head to the west. Grave goods were arranged around the body. Seated female figurines are a distinctive type of grave goods found in some A-Group burials. Luxury imported goods, such as beads of Egyptian manufacture, have also been excavated. Poorer graves, with a few simple grave goods or no grave goods, occur as well. These were initially classified by Reisner as another culture which he called the B-Group. At present, "B-Group" graves are considered to be evidence of lower status individuals in the A-Group.

Excavations of A-Group settlements suggest seasonal or temporary camps, sometimes reoccupied for a long time. A few sites have evidence of architecture, such as houses constructed of stone with up to six rooms. Three large (Terminal) A-Group centers were located at Dakka, Qustul and Seyala, where some elaborate burials have been recorded, but the archaeological evidence does not demonstrate the emergence of an early state.

Agriculture was practiced by the A-Group, who cultivated wheat, barley and lentils. Animal husbandry was certainly an important component of their subsistence economy, but evidence for it is scarce.

The chronology of the A-Group is divided into three periods:

1 Early A-Group, contemporary to the Nagada I and early Nagada II phases in Upper Egypt, with sites from Kubbaniya to Seyala;

2 Classic A-Group, contemporary to Nagada Ild-IIIa, with sites in Lower Nubia and south of the Second Cataract in the northern Batn el-Hajar region;

3 Terminal A-Group, contemporary to Nagada Illb, Dynasty 0 and the early 1st Dynasty, with sites in Lower Nubia and northern Upper Nubia.

The dating of the A-Group culture is still debated, however. Based on the evidence of Nagada culture artifacts in Lower Nubian graves, the A-Group arose in the first half of the fourth millennium BC. It is usually assumed that the A-Group disappeared in Lower Nubia during the Egyptian Early Dynastic period (1st-2nd Dynasties), as a consequence of Egyptian military intervention there.

The origins of the A-Group are not yet well understood. Trade contacts with Upper Egypt were an important factor in the social and economic development of the A-Group. In Nagada II times, trade with Upper Egypt greatly increased, as can be inferred from the great number of Nagada culture artifacts in A-Group graves. The occurrence of rock drawings of Nagada II-style boats at Seyala might suggest that this was an important trading center.

In the early 1st Dynasty, Egyptian policy in Nubia changed and raids were made as far south as the Second Cataract. Evidence of this is seen in a rock drawing at Gebel Sheikh Suleiman (near Wadi Halfa) recording a raid against the Nubians by a king of the 1st Dynasty (possibly Djet). A fortified Egyptian settlement was probably founded in the late 2nd Dynasty at Buhen, to the north of the Second Cataract.

Archaeological evidence points to a substantial abandonment of Lower Nubia in Old Kingdom times. Yet the occurrence of A-Group potsherds in the Egyptian town at Buhen dating to the 4th-5th Dynasties suggests that some A-Group peoples were still living in the region then. Moreover, the discovery of a few A-Group sites between the Second and Third Cataracts (between the Batn el-Hajar and Kerma) points to a progressive movement southward in Upper Nubia of A-Group peoples.

Abu Gurab

Along the edge of the desert plateau at Abu Gurab (29°54′ N, 31°12′ E) and neighboring Abusir, roughly 15km south of Cairo, lie the sites for the 5th Dynasty pyramids and sun temples. Except for a scattering of Early Dynastic cemeteries between the village of Abusir northward to the Saqqara plateau, no activity previous to the 5 th Dynasty has been attested in the immediate vicinity. Queen Khentkaues, the link between the 4th and 5th Dynasties, was buried at Giza, while her husband Weserkaf, the first king of the 5 th Dynasty, located his modestly sized pyramid in the northern part of Saqqara, near the north-east corner of the Zoser complex. Nonetheless, Weserkaf was the first king to build a sun temple, naming it "the Fortress of Re" R’). This is the first known sun temple and one of only two such structures preserved; the other was built by Nyuserre.

It is unclear why Weserkaf selected the previously unused site of Abu Gurab, approximately 5km north of his pyramid, but perhaps at the time of the sun temple’s construction the administrative capital and royal residence had already relocated in the vicinity of Abusir. Most of what we know about the activities of the new dynasty derives from this region.

According to the Middle Kingdom Tale of Djedi and the Magicians, the first three kings of the 5th Dynasty were triplets and the physical progeny of the sun god Re. There appears to be some truth behind this myth: not only were the second and third kings of the dynasty brothers, but these rulers also exhibited an unusually strong devotion to Re, particularly in his aspect as a universal creator deity. The sun temple itself offers proof of their piety, since it represented a new type of temple in many ways. Among other things, these temples were the first known instances of Egyptian monarchs dedicating large-scale stone structures entirely separate from their funerary monuments. No fewer than six kings of the 5th Dynasty are known to have built this kind of temple: Weserkaf, Sahure, Neferirkare, Reneferef or Neferefre, Nyuserre and Menkauhor.

Judging from the numerous references to this type of temple in official titles and other records, the sun temples were among the most important institutions in the land. Their great economic power is reflected in the fact that, according to the Abusir Papyri, offerings sent to the royal mortuary temples were dispensed first through the associated sun temples. Yet it appears that no single Egyptian term for sun temple exists.

Like the classical pyramid complex of the 4th Dynasty, a sun temple can be divided into three major sections according to function. First, there was a small valley temple at the edge of cultivation or an access canal; second, a relatively short causeway led up to the desert from the valley temple; and at the desert plateau stood the third and major part, the sun temple proper. The division of the complex into upper and lower portions was certainly dictated by practical considerations, but it also reflected a separation of the cult place from administrative buildings and the profane world in general. Excavations about the valley temple of Nyuserre’s sun temple have revealed that a small village of privately built houses sprang up there over the years, without doubt due to the temple’s importance to the local economy.

Because the central portions of the only two sun temples thus far located are so badly preserved, excavators have had to rely on the hieroglyphic signs in the temples’ names in order to reconstruct the shape of their characteristic feature, the obelisk. It is only from such textual evidence that we know that squat, perhaps even truncated, obelisks stood atop a platform and dominated the large rectangular open court of the upper temples. At Nyuserre’s sun temple the obelisk mentioned in an inscription from the Zoser complex was constructed out of irregularly shaped stone blocks ingeniously fitted together and may have risen to a height of approximately 35m. In some cases either a disk or a crosslike appendage may have been affixed to the top of the obelisk.

These first known obelisks in ancient Egypt are somewhat problematic. Although the obelisk and the sun temple have been connected with the "high sand of Heliopolis" and the Heliopolitan sun cult, the evidence does not bear these suppositions out. For one thing, the obelisk at Weserkaf’s sun temple appears to have been added much later by Neferirkare, the third king of the dynasty.

The influence of the sun cult is evident in the large court where sacrifices could be made in the bright sunlight, rather than in darkened inner chambers as is so often the case in Egyptian temples. In front of the obelisk was the altar where the presumably burnt offerings were made. The sides of the altar at Nyuserre’s temple were formed into four large hotep (offering) signs, each oriented roughly toward a cardinal point of the compass, a noteworthy example of the intimate relationship between art, architecture and writing in ancient Egyptian culture.

According to the Palermo Stone, a 5th Dynasty king list, Weserkaf established at his sun temple a daily offering to Re of two oxen and two geese. This largesse may not be an exaggeration, since the two surviving sun temples were both provided with sizable slaughterhouses; two, in the case of the sun temple of Nyuserre, named "Re’s Favorite Place" (Ssp-ib-R). The Abusir Papyri show that the slaughterhouses at the sun temples supplied the needs of the associated mortuary temples of the pyramid complexes. Some of the material distributed to the sister institution of Nyuserre’s mortuary temple would probably have come from the large covered storehouse containing several magazines that was located adjacent to the sun temple’s slaughterhouse.

Art that has survived at the sun temples seems to have been commissioned by Nyuserre. The so-called "Room of the Seasons" in Nyuserre’s sun temple, which linked a covered corridor with the obelisk platform, was decorated with a group of reliefs portraying the activities of man and animals through the three Egyptian seasons. Near these were other reliefs which depicted the Heb-sed festival, an important ritual of royal renewal. Nyuserre also had part of Weserkaf’s sun temple decorated with similar scenes from the same festival, but executed in a smaller scale. Most likely, chapels at both temples were used during the celebration. The reliefs in both places are executed in a fine, wafer-thin style that is characteristic of royal work of the 5 th Dynasty.

The area immediately to the south of the enclosure wall of Nyuserre’s sun temple has yielded another interesting feature, a large (30x10m) sun boat that was buried in a mudbrick-lined chamber to the south of the temple complex.

Abu Gurab/Abusir after the 5th Dynasty

With the reign of Djedkare Isesi, the eighth king of the 5th Dynasty, royal activity at Abu Gurab and Abusir abruptly ceased. Isesi did not erect a sun temple, and chose to be buried at South Saqqara. The Abusir plateau had become overcrowded by the reign of Menkauhor and the administrative capital may have been shifted back south to Saqqara again. Although there are no Old Kingdom tombs datable later than the 5th Dynasty, a number of loose blocks and stelae found near the mastabas show that Abusir certainly was not abandoned. This is not surprising because the Abusir Papyri reveal that the royal funerary establishments were still in operation as late as the reign of Pepi II (late 6th Dynasty). Although the papyri show that at times a large number of people were employed at these establishments or derived income from their endowments, the Abu Gurab/Abusir region was rarely used as a necropolis after the 5th Dynasty.

In the Middle Kingdom a number of tombs, whose superstructures are nearly all destroyed, were built near Nyuserre’s pyramid at Abusir. A small sanctuary dedicated to the chief goddess of the Memphite region was erected in the southern part of Sahure’s mortuary temple during the New Kingdom. It is uncertain how long this cult functioned. Thereafter, except for occasional burials during the Late period, the Abusir plateau seems to have fallen into disuse.

Abu Roash

Abu Roash is a village about 9km north of the pyramids of Giza (30°02′ N, 31°04′ E). It is chiefly known as the site of the 4th Dynasty pyramid of Djedefre (Redjedef), which was built on an eminence 2km west of the village, in the white limestone hills west of the Nile. In 1842-3, Richard Lepsius recorded this pyramid and a second one built of mudbricks, situated on the easternmost promontory of the hills. J.S. Perring, who visited Abu Roash five years before Lepsius, also thought the core belonged to a pyramid of "apparent antiquity." Current opinion is skeptical that the mudbrick construction is actually a pyramid, although Swelim identified it as such in his investigation of the site in 1985-6. Perhaps originally this structure was a large mastaba tomb. Long stripped of its bricks, this structure now consists of a bare rock core, part of an entrance corridor (sloping from north to south at an angle of 25°), and a rock-cut tomb chamber with a floor measuring 5.5m square and 5m in height. The mudbricks were laid over the rock core in accretion layers inclining inward at an angle of 75°-76°.

Apart from the excavation of tombs dating from the 1st-2nd Dynasties and the 4th-5th Dynasties, by A.Klasens for the Leiden Museum of Antiquities in 1957-9, all the major archaeological work at Abu Roash has been conducted under the auspices of the French Institute of Archaeology in Cairo. Emile Chassinat excavated at the stone pyramid complex in 1901-3, followed by Lacau in 1913. In 1995 a combined expedition of the French Institute and the Department of Egyptology of the University of Geneva began joint excavations under the direction of Valloggia at the stone pyramid, which are still in progress. The private tombs, mostly dating from the 1st-2nd Dynasties and the 4th-5th Dynasties, were excavated by P.Montet in 1913-14, and by Fernand Bisson de la Roque in 1922-5. The design of the earliest tombs and the high quality of some of the artifacts found in them demonstrated that their owners were high status individuals, suggesting that Abu Roash was an administrative center long before the time of Djedefre.

Djedefre, who reigned for at least eight years, was a son of Khufu, the builder of the Great Pyramid at Giza. All that remains of the superstructure of his pyramid is a flat-topped edifice, which measures about 98m square with a height of about 12m. Its core of rock is surrounded by about ten courses of local stone. All four sides were overlaid with red Aswan granite. When complete, each side of the pyramid at the base measured 106m (202 cubits) and its height would have been about 67m (128 cubits). The sides sloped inwards at an angle of approximately 52°. Possibly the granite casing was not intended to be higher than the present level of the core. Many centuries of demolition have resulted in the loss of virtually all the casing stones of the buildings in the complex leaving piles of granite chips, some as high as 5m.

A perpendicular shaft, measuring 23m east-west and 10m north-south, was sunk through the center of the rock to a depth of more than 20m. At the bottom were the burial chamber and at least one antechamber, probably built of granite, with access from a northern entrance corridor. The chambers may have had corbel roofs or roofs with superimposed relieving compartments, like those in the Great Pyramid. Only some fragments of the king’s granite sarcophagus have been found, but enough to suggest that it resembled the oval sarcophagus in the Unfinished Pyramid at Zawiyet el-Aryan.

The entrance corridor, now destroyed, opened low on the north face of the pyramid. Its length was about 49m, oriented 21′ west of north and with a slope of 26°, increasing to 28°. The flat roof was constructed of slabs of granite and the thick walls of local stone, faced on the inside with granite. The floor was paved with limestone. It was constructed in an open trench which varied in width from 5.5m to 7.0m. The corridor was only about 1m wide, but the trench needed to be wider so that the sarcophagus and massive floor blocks could be transported into the pyramid. This operation required enough space for workmen (and possibly oxen). Failure to make such a provision in the Great Pyramid may explain why Khufu’s sarcophagus had to be placed in the superstructure.

At the time of the king’s death, work on the mortuary temple on the east side of the pyramid had not advanced beyond the construction of a court with a granite-paved floor. The necessary buildings were hastily constructed of mudbrick overlaid with a thick layer of plaster, undoubtedly painted to simulate stone. Among the few objects found were statues of three sons and two daughters of Djedefre, a painted limestone female sphinx and a small wooden hippopotamus. Outside the pyramid on the south side was a pit for a wooden boat more than 37m long and 9.5m deep in the middle. A small subsidiary pyramid stood opposite the southwest corner of the main pyramid. A causeway 1500m in length and 14m wide linked the pyramid enclosure with the valley temple next to the floodplain.

Despite its ruined state, the pyramid complex of Djedefre has yielded much of archaeological importance. By their design, the oval sarcophagus and the wide trench for the entrance corridor to the pyramid have helped to establish the date of the Unfinished Pyramid at Zawiyet el-Aryan. The discovery of circular bases and part of the shaft of a round column have shown that free-standing round columns were in use at an earlier date than had been supposed. North of the pyramid is a large enclosure of a kind known from step pyramids but not used with true pyramids until the Middle Kingdom. The mortuary temple had a very different plan from that of any other known temple, and the 1500m causeway leading from the Wadi Qaren to the pyramid is without parallel. Also important are the many artifacts which have been found in the excavations, including, most notably, three fine quartzite heads from broken life-size statues of the king now in the Louvre and the Cairo Museum.

Near the mouth of the Wadi Qaren are the remains of a Coptic monastery mentioned by the Arab historian Maqrizi (AD 1364-1442) as being one of the most beautiful and best situated monasteries in Egypt. Built on a mound, it provided a fine view of the Nile. Also at the mouth of the wadi are the ruins of a mudbrick fort believed to date from the Middle Kingdom.

Abu Sha’ar

The late Roman (circa late third-sixth centuries AD) fort at Abu Sha’ar or Deir Umm Deheis (27°22′ N, 33°41′ E) on the Red Sea coast is circa 20km north of Hurgada and circa 2-3km east of the main Hurgada-Suez highway. The fort is circa 25m from the Red Sea at high tide. It sits on a natural sand and gravel bank several metres above the mud flats to the west; artificial ditches to the north and south augmented fort defenses. Visitors in the first half of the nineteenth century, including James Burton, J.G.Wilkinson, J.R.Wellsted and Richard Lepsius, erroneously identified the site with the Ptolemaic-Roman emporium of Myos Hormos, as have some subsequent visitors and scholars.

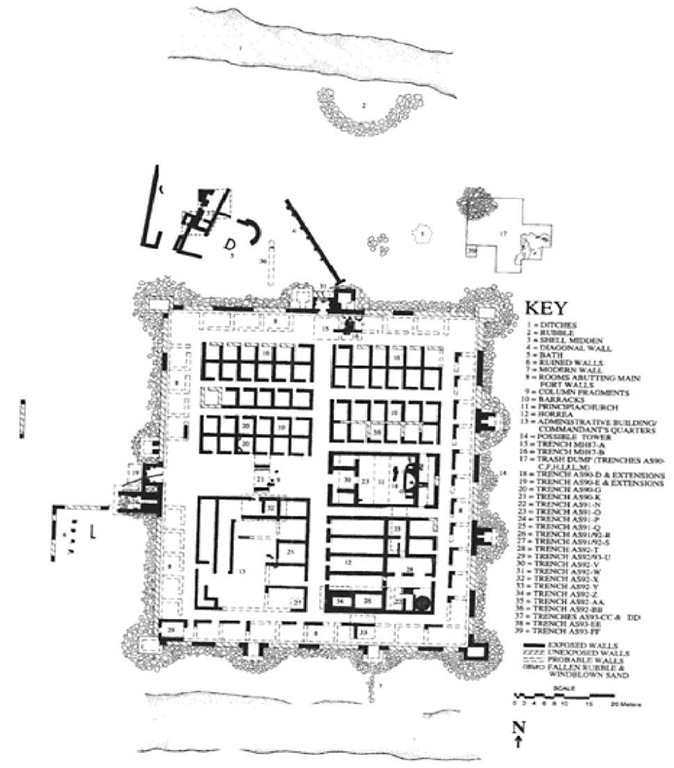

Excavations by the University of Delaware (1987-93) revealed a fort built as part of the overall late third-early fourth centuries AD reorganization of frontier defenses throughout the entire Eastern Roman empire. The fort at Abu Sha’ar is of moderate dimensions with defensive walls enclosing an area circa 77.5mx 64m. Walls were circa 3.5-4m high (including parapet) and 1.5m thick (including a 0.5m wide catwalk). The walls were built of stacked igneous cobbles (from the foot of Gebel Abu Sha’ar, 5.5-6km west of Abu Sha’ar) with little binding material (mud). The fort had 12-13 quadrilaterally shaped towers of unequal dimensions built of white gypsum blocks atop bases of gray igneous cobbles; the bottom interior portions of the towers were rubble filled. There were two main gates: a smaller one at the center north wall and a larger one at the center west wall. The main (west) gate was originally decorated with an arch and carved, decorated and painted (red and yellow) console blocks and other architectural elements. One or more Latin inscriptions recorded the Roman emperors Galerius, Licinius I, Maximinus II, Constantine I and the Roman governor Aurelius Maximinus (dux Aegypti Thebaidos utrarumque Libyarum). An inscription dates fort construction, or possibly "reconstruction," to AD 309-11. The garrison was a portion of the Ala Nova Maximiana, a mounted unit (probably dromedary) of approximately 200 men.

FOR I’ AT ABU SHA’AK

Figure 3 Plan of the fort at Abu Sha’ar as it appeared following the 1993 excavations

Gypsum catapult balls from the towers and fort indicate the presence of artillery. Sling stones suggest another mode of defense. No other weapons have been discovered nor is there evidence of deliberate destruction of the fort; it seems to have been peacefully abandoned by the military some time before the late fourth-early fifth centuries, a trend found elsewhere in the eastern Roman empire at that time. Following a period of abandonment, Christian squatters reoccupied the fort. Parts of the fort interior were used as trash dumps, while other areas were inhabited. The principia was converted into a church and the north gate became the principal entrance into the fortified area. Scores of graffiti, Christian crosses and two major ecclesiastical inscriptions in Greek at the north gate attest to the importance of Abu Sha’ar as a pilgrimage center at that time.

A short distance outside the fort northwest of the north gate was a semicircular bath built of kiln-fired bricks covered with waterproof lime mortar. Other rooms of the bath, including a hypocaust, lay immediately to the west. Adjacent to the bath and northeast of the north gate were trash dumps; the former was late fourth-early fifth centuries, the latter fourth century. Immediately outside the north gate was a low diagonal wall of white gypsum circa 22m long; its function remains unknown. The fort interior had 38-9 rooms abutting the inside faces of the main fort walls (average dimensions: 4.4-5.4×3.2-3.6m). These may have served multiple purposes including storage, guardroom facilities and, perhaps, living quarters. On the northern interior side were 54 barracks; 24 larger ones in the northeast quadrant averaged 3.0×4.0m. Thirty others in the northwest quadrant averaged 3.0-3.1x 3.3-3.4m. The lower walls were built of igneous cobbles circa 0.95m high, and the upper walls of mudbrick were of approximately the same height, for a total barracks height of circa 1.9m. Roofing was of wood (mainly acacia), matting and bundles of Juncus arabicus.

The principialchurch in the center-east part of the fort was 12.6-12.8x22m, and circa 2.4-2.6m high. It had an apse toward the east end, two rooms flanking the apse, and two rooms behind (east of) the apse which did not lead directly into the main part of the building. There were two column pedestals adjacent to (west of) the apse and there seem to have been wooden dividers separating the nave from the side aisles. Two smaller rooms at the west end flanked the building entrance. Roofing was of wood and bundled Juncus arabicus. A military duty roster dating no later than the fourth century, a Christian inscription of the fourth-sixth century, a textile cross embroidery, a 27-line papyrus in Greek from the fifth centuries, and human adult male bones wrapped in cloth were all found inside this building. The latter discovery in front of the apse suggested a cult of a martyr or saint, an especially popular practice in early Coptic religion.

The main entrance of the principialchurch faced east onto a colonnaded street which led to the main west gate. White gypsum columns (circa 46-8cm in diameter), sat on two parallel socles (stylobates) of gray igneous cobbles. At least two columns with spherical bases also decorated one or both of the stylobates. The street between the stylobates was circa 4.6-4.7m wide. The buildings in the south-eastern quadrant included five storage magazines (horrea) fronting the main north-south street. East of these in the same block were a kitchen, which included a large circular oven circa 3.4m in diameter made of kiln-fired bricks, small "pantries" and milling (grain olives) areas.

A road joined the fort at Abu Sha’ar to the main (parent) camp at Luxor via Kainopolis (Qena) on the Nile circa 181km to the south-west. This road, dotted with cairns, signal and route marking towers and installations, including hydreumata (fortified water stations), facilitated traffic between Abu Sha’ar and the Nile, supported work crews hauling stone from the quarries at Mons Porphyrites (first-fourth centuries AD) and Mons Claudianus (first-third/early fourth centuries AD) and assisted Christian pilgrims traveling between points in Upper Egypt and holy sites in the Eastern Desert (Abu Sha’ar, monasteries of St Paul and St Anthony), Sinai (such as the Monastery of St Catherine) and the Holy Land itself via Aila (Aqaba). The fort and road also monitored activities of the local bedouin (Nobatae and Blemmyes), and may also have protected commercial activity.