Interpretation of urine cultures

The correlation between clinical symptoms and the presence of infection is imprecise. In addition, it is frequently difficult to obtain a urine specimen that is uncontaminated by the normal microbial flora of the distal urethra, vagina, or skin. When evaluating urine cultures, therefore, the physician should consider both the species and the number of bacteria found.

Species Found on Urine Culture

More than 95% of UTIs result from a single bacterial species. Thus, in most instances, a culture that grows out mixed bacterial species is contaminated and needs to be repeated. Polymicrobial infection may occur in certain settings, however, including long-term catheterization, incomplete bladder emptying because of neurologic dysfunction, and the presence of a fistula between the urinary tract and the GI or genital tract. Organisms that are commonly found in the vaginal introitus and distal urethra, such as S. epidermidis, diphtheroids, and lactobacilli, seldom cause UTI except in complicated settings. Another marker of contamination is the presence of squamous epithelial cells in a urine specimen. On the other hand, pyuria is highly associated with inflammation of the urinary tract, which is most commonly caused by infection.

Bacterial Count on Urine Culture

The number of organisms per milliliter of a clean-voided urine specimen is a useful indicator.4 The growth of 105 or more colonies of a single bacterial species per milliliter of urine in two consecutive urine cultures is the diagnostic criterion for asymptomatic bacteriuria in women. In women with acute dysuria, the presence of at least 102 organisms/ml of a single coliform species appears to be a more accurate criterion for infection than a threshold of 105 organisms/ml. Women with dysuria and pyuria who have less than 102 bacteria/ml may have urethritis caused by Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, or herpes simplex virus or vulvovaginitis caused by Trichomonas vaginalis or Candida species. Clinical and laboratory criteria can help differentiate these conditions [see Table 2]. In men, the minimal level indicating infection appears to be 103 organisms/ml. In general, probably 70% of persons with true bacterial UTI will have more than 105 organisms/ml; 30% will have lower concentrations of bacteria.

The presence of organisms on a Gram stain of unspun urine is highly suggestive of significant bacteriuria; however, a negative Gram stain does not rule out infection. The Gram stain has excellent sensitivity for demonstrating bacteriuria when the urine colony count exceeds 105 organisms/ml but has poor sensitivity at lower colony counts.

Management

Antimicrobial therapy

In general, antimicrobial therapy is warranted for any symptomatic infection of the urinary tract. The choice of antimicrobial agent, dose, and duration of therapy depends on the site of infection and the presence or absence of complicating conditions. Therefore, each category of UTI merits a different approach on the basis of the particular clinical syndrome that is present.

Table 2 Common Causes of Acute Dysuria in Women68

|

|

|

Laboratory Findings |

|

||

|

Condition |

Pathogen |

Pyuria |

Hematuria |

Urine Culture (cfu/ml) |

Symptoms, Onset, and Factors |

|

Cystitis |

Escherichia coli (most common), Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Proteus species, Klebsiella species |

Usual |

Often |

102 to a 105 |

Abrupt onset, multiple symptoms (dysuria, increased frequency, and urgency), suprapubic or low back pain, suprapubic tenderness on examination |

|

Urethritis |

Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonor-rhoeae, herpes simplex virus |

Usual |

Rare |

< 102 |

Gradual onset, mild symptoms, vaginal discharge or bleeding (caused by concomitant cervicitis), lower abdominal pain, new sexual partner, cervicitis or vulvovaginal herpetic lesions on examination |

|

Vaginitis |

Candida species, Trichomonas vaginalis |

Rare |

Rare |

< 102 |

Vaginal discharge or odor, pruritus, dyspareunia, external dysuria, no increased frequency or urgency, vulvo-vaginitis on examination |

Treatment of Women with Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis

Antimicrobial therapy for healthy reproductive-age women with uncomplicated UTI should have the dual objective of eradicating the infection and eliminating uropathogenic clones of bacteria from the vaginal and GI reservoirs to prevent early recurrences. In general, the species and antimicrobial susceptibilities of the bacteria that cause acute uncomplicated cystitis are highly predictable. Thus, in otherwise healthy women presenting with typical symptoms of acute cystitis (dysuria and frequency without signs or symptoms of vaginitis), it is safe and cost-effective to omit the urine culture and use empirical short-course therapy. Three-day therapy seems to be optimal; single-dose therapy results in higher relapse rates (probably because of failure to eradicate the uropathogen from the vaginal reservoir), and 7-day therapy offers no additional benefit but costs more and causes more side effects. Therapy for 7 days, however, should be considered in women with a history of recent UTI, symptoms of more than 7 days’ duration, or diabetes.29

Several effective therapeutic regimens for acute uncomplicated cystitis in women are available [see Table 3]. Traditionally, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) has been recommended as first-line treatment.30,31 However, resistance of uro-pathogens to TMP-SMX is increasing and now approaches 15% to 20% in some communities.32,33 Because in vitro TMP-SMX resistance has been correlated with clinical and bacteriologic failure of TMP-SMX therapy, factors other than the expected prevalence of TMP-SMX resistance should also be considered. These include a history of recent use of TMP-SMX or another antimicrobial and recent travel to an area with high TMP-SMX-resis-tance rates.33

In such settings, an alternative first-line agent should be considered for empirical therapy.29,32,33 Many strains of E. coli that are resistant to TMP-SMX are also resistant to amoxicillin and cephalexin; thus, these drugs should be used only in patients infected with susceptible strains. Other ^-lactams, such as amoxi-cillin-clavulanate or cefpodoxime, can be used but are expensive and may be associated with higher relapse rates, probably because they fail to eradicate the uropathogen from the vaginal reservoir. Nitrofurantoin remains highly active against E. coli and most non-E. coli isolates (except for Proteus species, which are intrinsically resistant to the drug); however, 7 days of therapy may be required to achieve reasonable cure rates with this drug. Most fluoroquinolones are effective for short-course therapy of cystitis. In a randomized trial, 3-day regimens of cipro-floxacin (100 mg twice daily), double-strength TMP-SMX (160/800 mg twice daily), or ofloxacin (200 mg twice daily) were equally effective in the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis in women.34 In separate studies, 3-day regimens of TMP-SMX and ofloxacin were found to be equally cost-effective.35,36 Higher costs were associated with 3-day regimens of ampicillin, ce-fadroxil, and nitrofurantoin because of lower efficacy and higher rates of side effects.35,36 However, increasing fluoroquinolone use has been correlated with increased rates of fluoroquinolone resistance, which suggests that patients with uncomplicated cystitis should be treated with an agent other than a fluoro-quinolone, if possible.

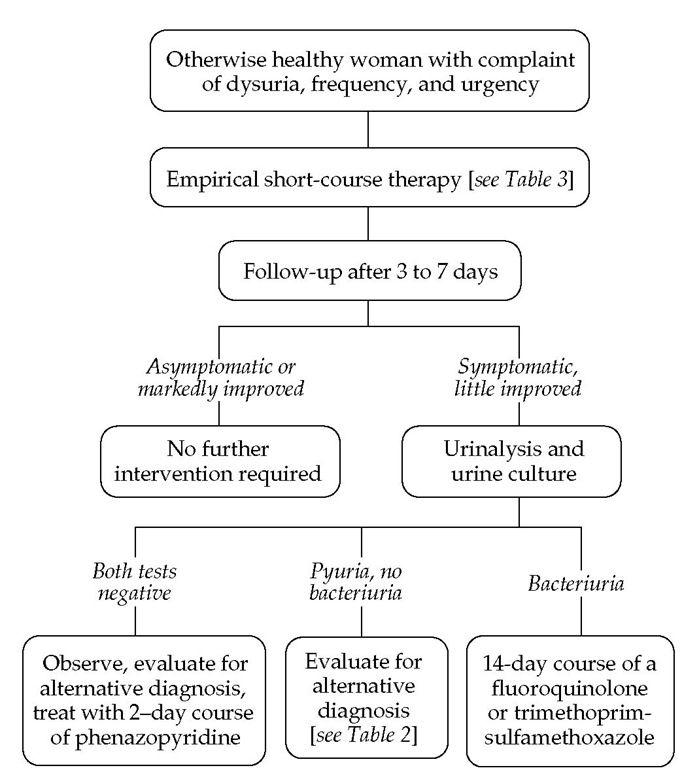

If a patient is still symptomatic after therapy, both urinalysis and urine culture are necessary [see Figure 2]. If the urinalysis and culture are negative, a 2-day course of the urinary tract analgesic phenazopyridine, 200 mg three times daily after meals, can be prescribed.38 A pelvic exam for evaluation of alternative diagnoses such as chlamydial, gonococcal, or herpetic infection should be considered, and close clinical follow-up is recom-mended.24 If testing shows pyuria but not bacteriuria, pelvic examination for alternative diagnoses should be performed. If the patient has both pyuria and bacteriuria, the antimicrobial susceptibility of the infecting strain should be assessed for resistance and an alternative agent should be given. Finally, a patient who is symptomatic after a short-course regimen and has persistent infection with a uropathogen that is sensitive to the antibiotic used should be regarded as having covert renal infection. In this circumstance, a 14-day course of a fluoroquinolone or TMP-SMX is indicated.

Table 3 Treatment Regimens for Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis4*

|

Host Considerations |

Empirical Treatment Regimens |

|

Otherwise healthy woman |

Three-Day Regimens |

|

TMP-SMX , 160/800 mg q. 12 hr |

|

|

Trimethoprim, 100 mg q. 12 hr |

|

|

Fluoroquinolones: Ciprofloxacin, 100-250 mg q. 12 hr |

|

|

Ciprofloxacin XR, 500 mg q.d. |

|

|

Gatifloxacin, 200 mg q.d. |

|

|

Levofloxacin, 250 mg q.d. |

|

|

Five- to Seven-Day Regimens |

|

|

Nitrofurantoin monohydrate/macro-crystals, 100 mg q. 12 hr |

|

|

Nitrofurantoin macrocrystals, 50-100 mg q.i.d. Amoxicillin, 250 mg q. 8 hr or 500 mg q. 12 hr |

|

|

Cephalexin, 250 mg q. 6 hr, or other cephalosporin |

|

|

Male sex, diabetes, symptoms for 7 days, recent antimicrobial use, age > 65 yr |

Consider Seven-Day Regimen |

|

TMP-SMX , 160/800 mg q. 12 hr |

|

|

Fluoroquinolones, as per 3-day regimen |

|

|

Cephalexin, 250 mg q. 6 hr, or other cephalosporin |

|

|

Pregnancy |

Consider Seven-Day Regimen |

|

Amoxicillin, 250 mg q. 8 hr or 500 mg q. 12 hr |

|

|

Nitrofurantoin monohydrate/macro-crystals, 100 mg q. 12 hr |

|

|

Nitrofurantoin macrocrystals, 50-100 mg q.i.d. |

|

|

Cephalexin, 250 mg q. 6 hr, or other cephalosporin |

|

|

TMP-SMX , 160/800 mg q. 12 hrt |

* Characteristic pathogens are Escherichia coli (85% to 90%) and Staphylococcus sapro-phyticus (5% to 15%); other organisms, which account for < 5% of cases, are Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterococcus species.

^Treatments listed are those to be prescribed before the etiologic agent is known (Gram stain can be helpful); regimens can be modified once the agent has been identified. The recommendations are limited to drugs currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration, although not all the regimens listed are approved for these indications. Optimal empirical regimens may differ among settings because of differences in the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of uropathogens. Fluoroquinolones should not be used in pregnancy.

‘Although TMP-SMX is classified as pregnancy category C, it is widely used; however, avoid use of this drug in the first and third trimesters of pregnancy. TMP-SMX—trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

Treatment of postmenopausal women The antimicrobial approach for postmenopausal women with symptomatic cystitis is similar to that for younger women—namely, short-course therapy with TMP-SMX or a fluoroquinolone initially; longer courses of therapy should be reserved for patients who do not respond to short-course therapy. In a randomized clinical trial of the treatment of acute cystitis in postmenopausal women, 3-day therapy with ofloxacin was more cost-effective than 7-day therapy with cephalexin.39 In another randomized trial, 3 days of ciprofloxacin for treatment of cystitis in women 65 years of age and older was equivalent to 7 days of ciprofloxacin and associated with fewer adverse effects.40 The major difference in the management of older women with UTI is the recognition that topical estrogen replacement, in the form of vaginal estriol cream, may decrease the incidence of recurrent UTI in postmenopausal women.17 Some studies of postmenopausal women have not found a protective effect with topical estrogen, particularly when it is delivered by pessary. The effects of systemic estrogen replacement on risk of UTI have not been studied in a randomized, controlled trial, but in general, a protective effect has not been demonstrated with this intervention.41,42

Treatment of recurrent UTI Recurrence of uncomplicated cystitis in reproductive-age women is common, and some form of preventive strategy is indicated if three or more symptomatic episodes occur in 1 year. A variety of antimicrobial strategies are available, but before embarking on one of them, the patient should try such simple interventions as voiding immediately after sexual intercourse and using a contraceptive method other than a diaphragm and spermicide. There is little evidence to support the former approach, but it is still often recommended, given the difficulty in adequately studying this behavior and the low morbidity associated with implementing it. Ingestion of cranberry juice has been shown to be effective in decreasing bac-teriuria with pyuria, but not bacteriuria alone or symptomatic UTI, in an elderly population.43 Cranberry juice was demonstrated to reduce the rate of recurrent UTI in younger women when combined with lingonberry.44 A more recent randomized trial comparing placebo, cranberry juice, and cranberry tablets also demonstrated a reduction in the UTI rate in young women from 32% in the placebo group to 20% with juice and 18% with tablets.45 Thus, although the efficacy of cranberry juice for prevention of UTI needs further evaluation, there is mounting evidence that it may be effective in young otherwise healthy women.46 This effect appears to be independent of any urinary acidification; rather, it is postulated that cranberry juice contains substances that inhibit the attachment of bacterial adhesins to the uroepithelium.

Figure 2 Clinical approach to acute uncomplicated cystitis in a woman.

If simple nondrug measures are ineffective, continuous or postcoital—if the infections are temporally related to intercourse—low-dose antimicrobial prophylaxis with one of several regimens should be considered. A single dose of TMP-SMX (one half of a single-strength tablet, which amounts to 40 mg of trimethoprim and 200 mg of sulfamethoxazole), a fluoroquin-olone (one tablet), or nitrofurantoin (50 mg; or 100 mg of nitrofu-rantoin macrocrystals) can safely and effectively decrease the rate of recurrent infections.18 Typically, a prophylactic regimen is initially prescribed for 6 months and then discontinued. If the infections recur, the prophylactic program can be instituted for a longer period. Antimicrobial prophylaxis has been effectively used for as long as 5 years in preventing recurrence of infection.8

An alternative approach to antimicrobial prophylaxis for women with less frequent recurrences (fewer than four a year) is to supply the patient with TMP-SMX or a fluoroquinolone and allow her to self-medicate with short-course therapy at the first symptoms of infection. The patient is directed to keep track of the number of such episodes and to contact the physician if more than four episodes occur over a 12-month period or if symptoms persist on such therapy. This approach has been shown to be safe and effective in two separate studies of women with recurrent UTI.4849

Treatment of relapsing infection The approach to the minority of patients with relapsing infection, as evidenced by finding the same bacterial strain in a UTI that occurs within 2 weeks after completion of antimicrobial therapy, is very different from the management of reinfection. Two factors may contribute to the pathogenesis of relapsing infection in women: deep-tissue infection of the kidney that is suppressed but not eradicated by a 14-day course of antibiotics, and structural abnormality of the urinary tract, particularly calculi. Patients with true relapsing UTIs should undergo radiologic or urologic evaluation and should be considered for longer-term therapy.