Vestibular Disorders

Benign paroxysmal positioning vertigo

The most common cause of vertigo in patients presenting for medical attention is BPPV.22 It is characterized by the vertigo and nystagmus that are associated with changes in head position. BPPV can occur after head trauma or prolonged periods of bed rest, or it can be precipitated by assuming unusual positions such as head extension in a dentist’s or hairdresser’s chair. Frequently, BPPV is idiopathic, especially in the elderly.

Pathophysiology

Dislocation of otoconia from the utricular macula likely underlies BPPV.18 These otoconia can migrate into the SCC (most often the posterior SCC), leading to canalolithiasis or possibly cupulolithiasis. A change in head position that promotes movement of the otoconia away from the cupula establishes a gravity-sensitive current, whereby stereocilia in the cupula move toward the kinocilium, resulting in the activation of that SCC [see Figure 2]. In the posterior canal, such movement produces depolarization and an irritative response in the vestibular nerve. For example, quickly moving a patient with a right posterior canal BPPV onto his or her right side (during either the Dix-Hallpike or the Semont maneuver) will produce activation of that canal.

The posterior SCC projects centrally to cranial nerve nuclei (IV and III) that mediate downward eye movements by innervating the ipsilateral superior oblique and contralateral inferior rectus muscles. This condition produces intorsion and depression of the ipsilateral (lower) eye and produces extorsion and depression of the contralateral (upper) eye.

Diagnosis of BPPV

Patients with BPPV describe vertigo provoked by head movement—most commonly, when turning over in bed, getting out of bed (matutinal vertigo), and reaching upward (e.g., toward a high shelf) with extension of the neck (so-called top-shelf vertigo). The vertigo is characteristically short-lived, generally not lasting longer than 15 seconds to 1 minute, although the episodes can be recurrent with repeated positional changes.23 For some patients, this form of vertigo is self-limited, whereas in others it is unrelentingly recurrent. Patients will often sleep with the affected ear up to avoid provoking the vertigo.

Positioning nystagmus can be provoked by performance of the Dix-Hallpike maneuver [see Table 2].24 This maneuver is performed with the patient seated on the examining table: the examiner turns the patient’s head 45° either to the right or the left, then rapidly moves the patient into the supine position with the head hanging 30° over the edge of the table.10 In patients with BPPV, nystagmus and vertigo then develop with a latency of 3 to, in rare instances, 30 seconds. Once the nystagmus subsides, the patient is returned to the sitting position; this may produce a recurrence of the vertigo. The maneuver is then repeated with the patient’s head turned to the other side. With repeated maneuvers, the vertigo tends to fatigue.

In patients with BPPV involving the posterior SCC, the Dix-Hallpike maneuver will indicate which labyrinth is affected. For example, when a patient with right posterior canal BPPV is moved into the supine position after the head is turned 45° to the right [see Figure 5], the slow phase of nystagmus will have a torsional component such that the upper pole of the eye moves toward the patient’s left and the vertical component moves downward (relative to the patient’s body). Quick phases of nystagmus will be opposite, with an upbeating vertical component and torsional quick phases beating toward the dependent right ear. (If the patient has not eliminated fixation, the vertical component of the nystagmus may be suppressed and only the torsional component observed.)

Treatment

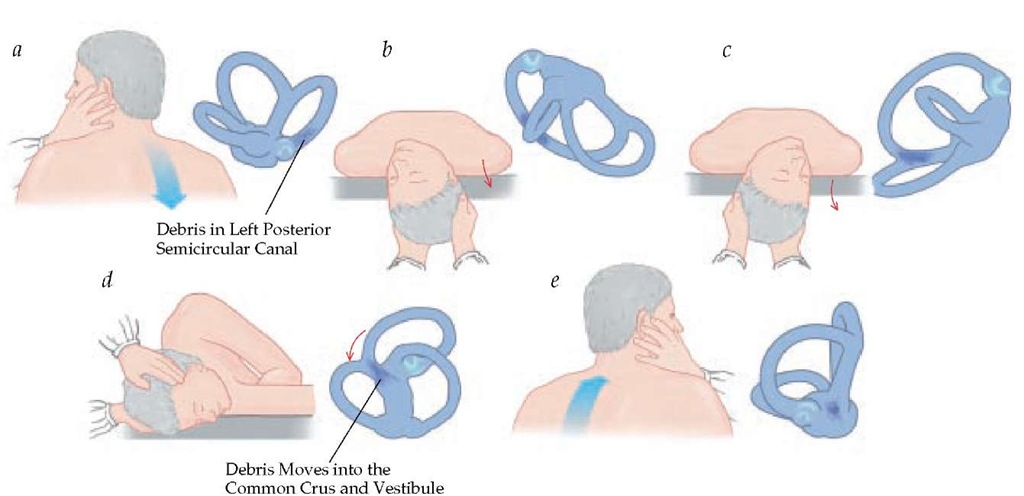

The treatment of BPPV involves the performance of maneuvers that aim to promote the repositioning of the otoconia from the SCC system (particle repositioning).25 One such maneuver, the Epley maneuver, begins in a fashion that is identical to the Dix-Hallpike maneuver except that the patient’s head is eventually moved through a complete turn rather than limited to only a left or right downward position [see Figure 5]. The movement of the head gradually directs the otoconia from the long arm of the canal into the vestibule, where it no longer causes symptoms. During the modified Epley maneuver, the initial head-hanging position with the involved ear down is maintained until the observed nystagmus has fatigued. The head is then turned, with the neck extended, until the noninvolved ear is facing downward. Nystagmus may recur at this point and should be in the same direction as it was when initially elicited. This second position is held until the nystagmus fatigues or for approximately 30 to 60 seconds. The patient is then rolled onto his or her side into a lateral decubitus body position, with the nose pointed downward, for another 30 to 60 seconds. Finally, the chin is tucked toward the chest and the patient is helped up into the seated position. The examiner must maintain contact with the patient at this point, because sitting up will sometimes elicit a vestibulospinal response, which may cause the patient to fall from the table. Two aspects of the original particle repositioning procedure have been found to provide no additional benefit: instructing the patient to sleep upright for 48 hours after treatment26 and the use of an oscillator over the mastoid during the maneuver.

Figure 5 With the Dix-Hallpike (a and b) and particle repositioning (c through f) maneuvers, the debris is sequentially moved further into the canal and ultimately to the vestibule, where it is effectively repositioned.

An alternative to the Epley maneuver, the Semont liberatory maneuver, involves the same theoretical elements as the Epley maneuver but utilizes a distinctly different procedure. The Se-mont maneuver is performed by rapidly moving the patient onto the left or right side and simultaneously rotating the head so that it is pointing toward the ceiling. This position is maintained for 30 to 60 seconds before the patient is rapidly moved into a face-down position on the opposite side of the table.

These maneuvers resolve BPPV in the majority of patients.30 When this form of therapy fails and BPPV is still the most likely diagnosis, the physician should repeat the Dix-Hallpike maneuver and apply a vibrator to the mastoid bone on the side of involvement while completing a standard particle-repositioning maneuver. The vast majority of patients with BPPV can be effectively treated in this fashion. Very rarely, BPPV is refractory to all conventional treatment interventions. In such cases, alternatives such as surgical neurectomy (singular neurectomy)31 or SCC occlusion32 may be necessary.

The use of a vestibular suppressant (e.g., diazepam, clon-azepam, or meclizine) is inappropriate for patients with probable BPPV. In general, these agents do not have a role in the treatment of BPPV.

Vestibular neuritis

After BPPV, the second most common cause of vertigo is vestibular neuritis, also known as acute peripheral vestibu-lopathy.33 The condition was previously called vestibular neu-ronitis, but it is now believed that inflammation occurs in the nerve itself and not generally in the vestibular ganglion.

Diagnosis

Patients with vestibular neuritis experience severe rotational vertigo, often associated with nausea and vomiting. Typically, the examiner will observe a horizontal-torsional nystagmus beating, with the fast phase toward the normal ear and the slow phase toward the abnormal ear. Hearing is typically preserved, differentiating this condition from labyrinthitis, in which hearing is typically affected. Symptoms often abate in 48 to 72 hours, although complete recovery may take as long as 6 weeks. Vestibular neuritis is often preceded by an upper respiratory tract infection. A number of infectious agents have been associated with vestibular neuritis [see Table 7].

Treatment

Corticosteroids are effective for the treatment of acute vestibular neuritis [see Table S].34 No benefit with antiviral treatment has been found. Symptomatic therapy with antiemetics and vestibular suppressants such as meclizine, diazepam, or promethazine can be used initially, but such agents may prolong the recovery process by preventing CNS adaptation and can also produce excessive sedation that predisposes patients (especially the elderly) to a greater risk of disequilibrium and injury. Hence, vestibular-suppressive agents are recommended only during the initial acute period of vestibulopathy (24 to 72 hours). They can be used in combination with stimulants such as caffeine and methylphenidate (5 to 10 mg every 6 to 8 hours), thereby minimizing daytime sleepiness. In patients with dehydration secondary to vomiting and diaphoresis, re-hydration is obviously also essential.

|

Table 7 Infections and Inflammatory Conditions Associated with Vestibular Neuritis |

|

|

Adenovirus |

Lyme disease |

|

Cytomegalovirus |

Otitis media/interna |

|

Enterovirus |

Sarcoidosis |

|

Epstein-Barr virus |

Syphilis |

|

Hepatitis |

Tuberculosis |

|

Herpes simplex virus |

Varicella-zoster virus (Ramsay |

|

HIV |

Hunt syndrome) |

|

Influenza |

|

Vestibular neuritis is generally self-limited, but occasionally, a failure of the compensation process that is required to adapt to a residual loss of function will cause patients to have continued symptoms. If, after an initial monophasic vestibular event, patients continue to complain of dizziness provoked by head movement, then rehabilitation with daily home exercises is indicated. Such rehabilitation, which can be supervised by physical or occupational therapists or even primary care nurses or physician extenders, results in significant improvement in the majority of patients.35 BPPV also frequently occurs weeks or months after vestibular neuritis.

Meniere disease

Pathophysiology

Meniere disease is thought to involve the accumulation of excessive endolymphatic fluid within the labyrinth. The term endolymphatic hydrops36 is sometimes applied to Meniere disease, on the basis of the pathologic appearance of the temporal bone in postmortem examinations, although this finding is often present in temporal bones from asymptomatic persons.36 Idiopathic periodic microruptures in the labyrinthine sac allow mixing of potassium-rich endolymph with perilymph. Cranial nerve VIII, located in the perilymph, becomes hyperpolarized when exposed to potassium-rich endolymph. The consequence of unilateral cranial nerve VIII hyperpolarization is a vestibular functional asymmetry culminating in nystagmus, vertigo, postural instability, and vegetative symptoms.

Table S Treatment Schedule for Acute Vestibular Neuritis

|

Treatment Day |

Oral Methylprednisolone, Single Daily Dose (mg) |

|

1-3 |

100 |

|

4-6 |

80 |

|

7-9 |

60 |

|

10-12 |

40 |

|

13-15 |

20 |

|

16-18 |

10 |

|

19 |

0 |

|

20 |

10 |

|

21 |

0 |

|

22 |

10 |

Diagnosis

Meniere disease involves attacks of vertigo that are typically associated with hearing loss, tinnitus, and a sensation of pressure or fullness in the affected ear. Both clinical and laboratory criteria are used for diagnosis [see Table 9]. Attacks are paroxysmal and generally last between 2 and 24 hours. Often, a history of high sodium intake hours before an attack can be elicited. Patients with Meniere disease may experience sudden falls, and they usually describe the perception of being thrown to the floor (otolithic crisis of Tumarkin). This probably results from abnormal excitation of the otolith organs leading to inappropriate vestibulospinal responses.

The nystagmus observed in patients with Meniere disease is similar to that observed in patients with other forms of peripheral vestibulopathy, such as vestibular neuritis. As such, the nystagmus is mainly horizontal with a torsional component and will decrease in intensity with visual fixation.

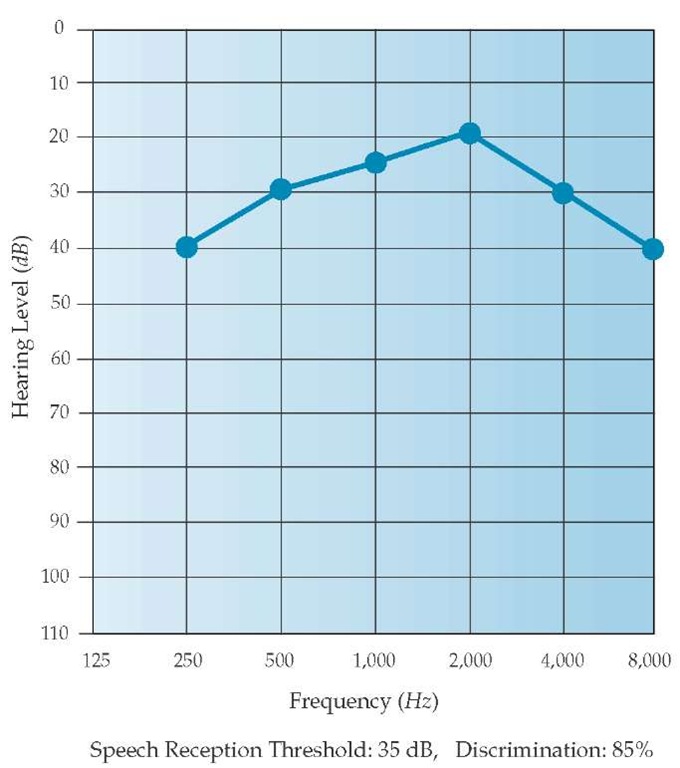

Patients with Meniere disease typically lose hearing over time. Low-frequency hearing is most affected early in the disease course, whereas high-frequency hearing loss is a late manifestation. These losses, together with relative preservation of middle-frequency hearing, produce a characteristic audiogram pattern referred to as a peak audiogram [see Figure 6].K Results of transtympanic electrocochleography are also abnormal in most patients with Meniere disease, suggesting an inner-ear fluid im-balance.39 This test is rarely used in clinical practice, however.

The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with a Me-niere-type disease is varied [see Table 10]. A number of familial autosomal dominant conditions are associated with periodic vertigo. For example, in its chronic stages, otosclerosis leads to conductive hearing loss and can involve the labyrinth, producing sensorineural hearing loss and vestibulopathy.

Treatment

Conservative treatment of Meniere disease consists of dietary-salt restriction and diuretic agents. Betahistine, a hista-mine analogue, is prescribed for Meniere disease in many countries, but it has not been approved for use in the United States and the balance of evidence does not support its use.41

For acute attacks of vertigo, vestibular suppressants are often helpful in combination with antiemetics. In cases that do not respond to medical treatment, the standard therapy is becoming intratympanic gentamicin, which results in a partial chemical labyrinthectomy, with a small risk of hearing loss.33 Surgical resection of the vestibular nerve is also effective, albeit more invasive.42 Endolymphatic shunting is sometimes performed but has not clearly been shown to be beneficial. Pressure devices are currently undergoing study and may become a minimally invasive treatment option.43

Phobic postural vertigo

Diagnosis

With phobic postural vertigo, patients report a subjective balance disturbance despite normal results on balance testing.44 Common complaints include postural vertigo and fluctuating unsteadiness, often associated with anxiety and vegetative symptoms. Attacks of vertigo are typically associated with particular perceptual stimuli, such as exposure to malls, bridges, staircases, or specific social situations.

Table 9 Diagnostic Criteria for Meniere Disease82

|

Possible |

Episodic vertigo of the Meniere type without documented hearing loss or Sensorineural hearing loss, fluctuating or fixed, with disequilibrium but without definitive episodes |

|

Probable |

One definitive episode of vertigo Audiometrically documented hearing loss on at least one occasion Tinnitus or aural fullness in the treated ear |

|

Definite |

Two or more definitive spontaneous episodes of vertigo lasting 20 min or longer Audiometrically documented hearing loss on at least one occasion Tinnitus or aural fullness in the treated ear |

|

Certain |

Definite Meniere disease, plus histopathologic confirmation |

Note: all classifications require that other causes are excluded [see Table 10].

Phobic postural vertigo is most commonly observed after the onset of a stressful event or recent illness, especially a vestibular disorder. Many patients who experience vestibu-lopathy initially use adaptive behavioral mechanisms (e.g., walking with assistive devices and utilizing furniture and walls for stability) to avoid falling. Unfortunately, many pa- tients persist in utilizing these mechanisms long after the vestibulopathy or stressful event has resolved. Ultimately, most of these patients exhibit elements of anxiety and phobia that are most prominent when ambulating. This condition should not be confused with malingering; rather, it is a defensive reaction, often with associated autonomic features (e.g., hyperventilation45 and tachycardia) that exacerbate the dizziness and perpetuate the maladaptive behavior.

Figure 6 The audiogram demonstrates the characteristic pattern of hearing loss observed in patients with inner-ear fluid imbalances such as Meniere disease. The reduction in low-frequency and high-frequency hearing and the relative preservation of middle-frequency hearing is referred to as a peak pattern.