Papulosquamous disorders comprise a group of dermatoses that have distinct morphologic features.1 The characteristic primary lesion of these disorders is a papule, usually erythematous, that has a variable amount of scaling on the surface. Plaques or patches form through coalescence of the primary lesions. Some common papulosquamous dermatoses are pityriasis rosea, lichen planus, seborrheic dermatitis, tinea corporis, pityriasis rubra pi-laris, psoriasis [see 2:III Psoriasis], and parapsoriasis. Drug eruptions, tinea corporis, and secondary syphilis may also have a papulosquamous morphology. Some papulosquamous disorders may be a cutaneous manifestation of AIDS.

Pityriasis Rosea

Pityriasis rosea is a relatively common, self-limited, exanthem-atous disease characterized by oval papulosquamous lesions on the trunk and proximal areas of the extremities. Pityriasis rosea typically appears during the spring and fall in temperate cli-mates3; its incidence is highest in persons between 10 and 35 years of age.

A population-based 10-year epidemiologic survey identified 939 patients with pityriasis rosea, about one third of whom had antecedent acute infection or atopy.5 It also showed that peak incidence occurred at 20 to 24 years of age, that the incidence was higher in colder months, and that recurrences were rare. Occurrences among household contacts are uncommon. This study also noted that the incidence of disease had appeared to decline.

Etiology

A viral etiology has been suggested for pityriasis rosea on the basis of immunologic and histologic data. The superficial dermis contains aggregates of CD4+ helper T cells in perivascular locations and increased numbers of Langerhans cells. It has been postulated that IgM antibodies to keratinocytes cause the secondary form of the eruption. An association between human herpesvirus type 7 (HHV-7) and pityriasis rosea was initially reported in 1997.6 Studies using polymerase chain reaction and im-munohistochemical analyses of tissue samples to detect HHV-7 DNA sequences and antigens have provided inconclusive evidence of a causal relationship between HHV-7 and pityriasis rosea. In a retrospective study of 13 patients and 14 control subjects, the prevalence of HHV-7 was lower in lesional skin of patients with pityriasis rosea than in control subjects.7 A subsequent seroepidemiologic study of HHV-6 and HHV-7 was conducted in 44 patients with pityriasis rosea and in 25 patients with other skin eruptions. Although in this study several patients with pityriasis rosea had antibody titers consistent with active infection, the overall prevalence of HHV-6 and HHV-7 was no greater in patients with pityriasis rosea than in control subjects.8 A meta-analysis reviewed the data from 13 studies and found insufficient evidence to support a causal relationship between HHV-7 infection and pityriasis rosea.9 A viral etiology of pityria-sis rosea thus remains elusive. Certain drugs that cause a pityria-sis rosea-like eruption have been implicated in the etiology of this disorder. These drugs include the antihypertensive agent captopril, metronidazole, isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid), peni-cillamine, arsenic, gold, bismuth, barbiturates, and clonidine.4

Diagnosis

The primary lesion, called a herald patch, appears first as a slightly raised, salmon-colored oval patch with a fine, wrinkled scale resembling cigarette paper. Typically, 7 to 10 days after the appearance of the herald patch, there occurs a bilaterally symmetrical eruption of smaller lesions; this secondary eruption occurs mainly on the trunk and upper extremities [see Figure 1]. Secondary lesions tend to follow cleavage lines (Langer lines) in a so-called fir tree distribution. A V-shaped formation on the upper chest and upper back, a circumferential pattern around the shoulders and hips, and a transverse pattern on the lower anterior trunk and lower back are seen in most patients.10 The lesions are occasionally pruritic. The secondary rash is frequently more helpful in making a diagnosis than the initial herald patch, which is often misdiagnosed.10 Atypical manifestations occur in 20% of persons affected. Such manifestations include a purpuric form of pityriasis rosea that resembles vasculitis, as well as papular, vesicular, pustular, and urticarial forms. An inverse variant of pityriasis rosea, more common in children than in adults, is characterized by lesions on the face and extremities, with relatively few lesions appearing on the trunk.4

Differential diagnosis

Because lesions of pityriasis rosea may closely resemble those of secondary syphilis, a serologic test for syphilis may be indicated. Lesions may also resemble tinea corporis or tinea versicolor and should be examined by fungal scrapings and potassium hydroxide (KOH) wet mounts. A careful drug history must be obtained to exclude the possibility of a drug eruption.

Treatment

Pityriasis rosea lesions resolve spontaneously after 6 to 8 weeks. The patient should be reassured that the disorder is benign and self-limited; such reassurance, together with educating the pa- tient about the disease, is the most important aspect of treatment.

Figure 1 Pityriasis rosea commonly presents as a single, large salmon-colored plaque called a herald patch (arrow). Appearance of the isolated lesion is followed in a week to 10 days by a bilaterally symmetrical papulosquamous eruption, mainly on the trunk and upper extremities.

Figure 2 Violaceous, flat-topped, polygonal papules are typical of lichen planus. A common location is the flexor aspect of the wrists and forearms.

Lesions are variably pruritic. Symptoms should be treated with bland emollients or systemic antipruritics. Sun exposure may accelerate clearing. Irradiation with ultraviolet B (UVB) sunlamps is beneficial in decreasing the severity of disease, especially when treatment is initiated within the first week of the eruption. One study found that 10 erythemogenic exposures of UVB substantially decreased the extent of pityriasis rosea, although it neither altered the duration of the disorder nor improved the itching.11 Other evidence suggests that UVB therapy may hasten resolution of the rash but may cause hyperpigmentation.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in India, oral erythromycin administered in divided doses for 14 days was effective in treating patients with pityriasis rosea.13 In this cohort, upper respiratory tract infections preceded the skin eruption in 68.8% of the 90 patients. A complete response, with complete resolution of skin lesions occurring within 2 weeks, was reported in 33% of the treatment group, as compared with 0% in the placebo group. The duration of disease was comparable for the two groups of patients. Although not all patients with pityriasis rosea benefit from erythromycin therapy, a trial of erythromycin is a safe treatment approach.

Lichen Planus

Lichen planus is a localized or generalized eruption with violaceous, flat-topped, polygonal papules and little or no observable scaling [see Figure 2]. It is often localized to the oral mucosa; 25% of patients with oral lichen planus have skin involvement as well.14 The incidence is highest in young to middle-aged persons.

Lichen planus usually appears in the fifth or sixth decade and affects women more often than men.

Etiology

The etiology of lichen planus is unknown. An alteration in basal keratinocytes that induces humoral and cell-mediated immune responses has been postulated as a mechanism. Skin and mucous membrane lesions resembling lichen planus have been observed in patients with graft versus host disease (GVHD) [see 2:VI Cutaneous Adverse Drug Reactions]. Lichen planus has also been associated with other immune-mediated diseases, including ulcerative colitis, bullous pemphigoid, myasthenia gravis with thymoma, primary biliary cirrhosis, and chronic active hepatitis.

There is an increased prevalence of viral hepatitis, especially hepatitis C, in patients with lichen planus. In a multicenter study of 303 sequential patients with lichen planus, the prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) was 19.1%, compared with 3.2% in control subjects.16 The role of HCV in the pathogenesis of lichen planus is not clearly understood; some investigators suggest that the cause of lichen planus may be related to the pattern of immune dysregulation induced by HCV.17 There are a number of reports of lichen planus occurring after administration of different types of hepatitis B vaccine.18 This is a rare occurrence, considering the widespread use of this vaccine; several cases have been reported from France and Italy, and one case has been reported from the Middle East. An immunologic mechanism has been postulated as the cause. The latency period ranges from several days to 3 months after any one of the three usual injections of vaccine.

A variety of drugs have been reported to cause lichenoid reactions in the skin, usually sparing the mucous membranes. Such drugs include beta blockers, methyldopa, penicillamine, quini-dine, and quinine. Other drugs that have been implicated but for which causal evidence is insufficient include angiotensin-con-verting enzyme inhibitors, sulfonylurea agents, carbamazepine, gold, and lithium.19 In one study, the administration of penicil-lamine for primary biliary cirrhosis was followed by the development of lichen planus in 17 of 24 patients20; in addition, after treatment with penicillamine, the skin eruption became worse in three of seven patients with biliary cirrhosis and preexisting lichen planus. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have been documented to cause a lichenoid drug eruption; these drugs include naproxen, indomethacin, diflunisal, ibuprofen, acetylsali-cylic acid, and salsalate.21 Although the latency period is highly variable, symptoms usually develop within a few months after drug initiation and resolve within weeks to months after discontinuance of the offending agent.

Diagnosis

Lichen planus appears as flat-topped, shiny, violaceous papules, often with a fine, reticulated scale on the surface. Common sites of involvement include the skin, nails, mucous membranes, vulva, and penis. Wickham striae—white, lacy patterns on the papule surface—are apparent on magnification with a hand lens.22 The occurrence of papules along a scratch line, as in linear lichen planus, is referred to as the Koebner phenomenon [see Figure 3]. In the hypertrophic form of the disease, papules coalesce to form thick plaques or nodules that are often found on the lower extremities. Pruritus may be severe, particularly in the generalized or hypertrophic forms of the disease. Common sites of involvement are the flexor surfaces of the wrists, the sacrum, the mucous membranes of the mouth, the medial thighs, and the genitalia. Mucous membrane lesions show a white, reticulated mosaic pattern [see Figure 4]. A severe erosive form of lichen planus can involve the oral mucous membranes. In rare cases, lesions occur in the esophagus, causing esophageal stricture and dysphagia.

A follicular form known as lichen planopilaris may result in scarring alopecia. Variants of lichen planus with distinct morphologic features include actinic, annular, bullous, hyper-trophic, linear, ulcerative, and zosteriform forms. The nails may also be involved [see 2:XIV Diseases of the Nail]. The clinical features of some forms of lichen planus may resemble those of lupus erythematosus.22

Skin biopsy confirms the clinical diagnosis of lichen planus. Typically, the epidermis shows hyperkeratosis, a prominent granular layer, liquefaction degeneration of the basal cell layer, and an intense upper dermal inflammatory infiltrate. Immuno-peroxidase studies using monoclonal antibodies to cell surface antigens have shown that most cells in the infiltrate are of the helper-inducer T cell subset. Colloid bodies (Civatte bodies) coated with immunoglobulin are frequently seen in the dermal papillae. On ultrastructural examination, numerous Langerhans cells can be observed at the dermoepidermal junction.

Treatment

Limited data exist for making evidence-based recommendations regarding treatment of lichen planus.24,25 Definitive clinical trials have not been performed, and information on the efficacy of treatments is derived from small trials and anecdotal evidence.

Body Lesions

Emollients, topical glucocorticoids, a short course of systemic corticosteroids, and systemic antipruritics have been used to treat cutaneous lichen planus. Most experts recommend medium- to high-potency topical corticosteroids as first-line treatment for localized cutaneous lichen planus. Oral corticosteroids may be used for generalized cutaneous lichen planus. As an alternative to systemic corticosteroids, systemic retinoids, such as aci-tretin, are beneficial in some patients with cutaneous forms of lichen planus.26 Azathioprine has been used for its steroid-sparing effect in erosive and generalized lichen planus.27

Other therapies that have been reported to have efficacy in the treatment of cutaneous lichen planus include phototherapy (psoralen plus ultraviolet A [PUVA]), cyclosporine, and hydrox-ychloroquine.24

Figure 3 The Koebner phenomenon—the appearance of lesions along a scratch line—may be seen in patients with lichen planus.

In a trial of oral psoralen photochemotherapy for widespread recalcitrant lichen planus, clinical remission occurred in six of seven patients and correlated with the disappearance of the upper dermal infiltrate.28 Oral cyclosporine has also been effective, but potential renal toxicity and hypertension limit its long-term use.22 Recombinant interferon alfa-2b, administered subcutaneously every other day, was successful in the treatment of generalized lichen planus in three patients with no evidence of hepatitis, further supporting the cell-mediated im-munologic etiology of this disease.29

Mouth Lesions

For lichen planus that is localized to the oral mucosa, a high-potency corticosteroid such as clobetasol in a vehicle that is adherent to the mucosal surface (Orabase) is helpful.24,29 Intrale-sional injections of corticosteroids may be used to treat localized, recalcitrant lesions. Use of miconazole gel in combination with chlorhexidine mouth rinses is effective for prophylaxis against oral candidiasis.30 Topical isotretinoin gel is an effective alternative to corticosteroids, although relapses often occur after discontinuance of this medication.31 In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 22 patients with biopsy-proven oral lichen planus, an 8-week course of 0.1% isotretinoin gel was found to be effective.31 Cyclosporine mouth rinses have been helpful for some patients. A 6-month course of hydroxychloroquine, 200 to 400 mg daily, was successful in nine of 10 patients with oral lichen planus; ulcers healed and pain decreased after 1 to 2 months.32 Topical tacrolimus, a macrolide that suppresses T cell activation, was used to treat erosive mucosal lichen planus in 19 patients whose conditions were resistant to conventional treatment. Therapeutic levels of tacrolimus were demonstrated in eight patients, and areas of ulceration showed a mean decrease of 73.3% over the 8-week study period; however, 13 of 17 patients suffered a relapse after cessation of therapy.33 Topical pimecrolimus cream is being evaluated as a treatment for oral erosive lichen planus.34 The role of these agents in the treatment of lichen planus must be further investigated, particularly in view of the alert by the Food and Drug Administration issued in 2005 regarding a possible link between use of topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus and cases of lymphoma and skin cancer.

Genital and Perianal Lesions

Mild, nonerosive disease can be controlled with topical corti-costeroids; erosive disease, although more difficult to treat, may be treated with topical corticosteroids in combination with other topical or systemic medications.35 Topical tacrolimus36,37 and topical pimecrolimus38 may be useful in the treatment of recalcitrant cases that have failed to respond to other therapies.

Figure 4 Lichen planus of the mucous membrane assumes a white, reticulated mosaic pattern, as seen above on the buccal mucosa.

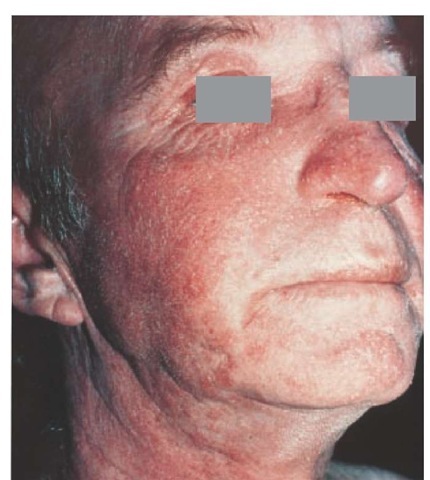

Figure 5 Seborrheic dermatitis seen on the face of this patient involves sites of sebaceous gland activity.

Prognosis

Patients who experience an acute outbreak of lichen planus have a good prognosis; in most cases, the papules clear within several months to a year. The chronic form, however, may last for 10 years or longer. In a study following the long-term course of lichen planus in 214 patients for 8 to 12 years, lichen planus cleared in two thirds of the patients within 1 year. The recurrence rate was 49%, which was higher than recurrence rates reported in previous studies; the authors attributed the high rate of recurrence to treatment with potent topical corticosteroids.39

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis is a papulosquamous condition that is often associated with excessive oiliness or seborrhea, dandruff, and well-defined red, scaly patches on the face, trunk, and intertrigi-nous areas.40 Some cases may progress to a severe exfoliative ery-throderma. Seborrheic dermatitis is a common skin disorder that occurs in otherwise healthy adults. It is increasingly prevalent in middle-aged and elderly persons. Seborrheic dermatitis does not occur before puberty except during infancy (usually between 2 and 12 weeks of age), at which time transplacentally derived maternal hormones are present. The prognosis in adults is one of lifelong recurrence, with each episode lasting weeks to months.

Etiology

The cause of seborrheic dermatitis is unknown. An occasional association with neurologic abnormalities, especially parkinson- ism, has been observed. Genetic predisposition, emotional stress, diet, hormones, and climatic factors may also influence this disorder. It is thought that an association exists between the yeastlike organism Pityrosporum and seborrheic dermatitis. Seborrhe-ic dermatitis may, in part, be the result of an abnormal or inflammatory immune response to this yeast, or it may be caused by an epidermal hyperproliferation of this organism.41

Patients with classic seborrheic dermatitis may have normal or reduced rates of sebum excretion; therefore, seborrhea is not essential for the development of this disorder.42 However, sebor-rhea may play a role in the seborrheic dermatitis present in certain patients, such as those with parkinsonism. Reduction of seb-orrhea with improvement of the dermatitis has been observed after a favorable neurologic response to levodopa treatment for parkinsonism.

Diagnosis

The scale associated with seborrheic dermatitis may be yellowish and either dry or greasy. Sites of predilection are the areas of sebaceous gland activity [see Figure 5], such as the scalp, eyebrows, eyelids, forehead, nasolabial folds, and presternal or interscapular regions. Blepharitis involves granular inflammation of the lid margin, with scaling and shedding of debris into the eye, which may cause conjunctivitis. Seborrheic dermatitis is the most common cause of otitis externa. When the scalp is involved, lesions often extend along the frontal hairline, forming a band of erythema. The postauricular area is a common site of involvement. Lesions of the trunk may consist of erythematous follicular papules covered by greasy scales, which may coalesce to form large plaques or circinate patches. Seborrheic dermatitis can be seen in areas of male pattern baldness, but it is not a cause of hair loss unless there has been a severe intervening secondary infection resulting in a scarring alopecia.