Clinical presentations Pulmonary Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis begins as a pulmonary infection, but many patients never develop symptoms, and others have an acute illness with fever, cough, and a pulmonary infiltrate that is diagnosed as an atypical pneumonia. Overwhelming pulmonary disease with ARDS can occur; this appears to be more common in older adults.30 Whether severe infection occurs because the patient has been exposed to a large number of conidia or has a defect in his or her immune response has not been clarified.

A more common presentation is a subacute to chronic pulmonary infection that is clinically and radiographically similar to tuberculosis. Fever, night sweats, weight loss, and fatigue are common symptoms. Cough, sputum production, hemoptysis, and dyspnea are noted. The lesions may be cavitary, nodular, fi-brotic, or masslike in appearance.31,32 Hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy and pleural effusions are uncommonly seen.

Disseminated Blastomycosis

Many patients with blastomycosis have no pulmonary symp-toms.26,31 They present with cutaneous lesions that are well circumscribed, nonpainful papules, nodules, or plaques that often become verrucous and develop punctate drainage areas in the center. The lesions are common on the face and extremities but can appear anywhere. There may be only a single lesion, or there may be multiple lesions. An uncommon manifestation seen mostly in immunocompromised patients is the appearance of hundreds of acute pustular lesions associated with widespread visceral involvement and an acute downhill course.

Additional manifestations of disseminated blastomycosis include prostatitis, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, laryngeal and oropharyngeal nodules, and, less commonly, central nervous system involvement. Genitourinary involvement may be asymptomatic, or it may be associated with signs of prostatism. Although osteoarticular infection can be associated with a contiguous skin lesion, bone involvement often occurs at sites distant from the cutaneous lesions. It is helpful to obtain a bone scan for all patients with disseminated blastomycosis because of the propensity of the organism to seed into bone and because osteomyelitis requires prolonged antifungal therapy. All patients with manifestations of dissemination, even patients with only one skin lesion, need to be treated with systemic antifungal therapy to prevent progression of disease.

Diagnosis Culture

The most definitive method for diagnosing blastomycosis is growth of the organism from an aspirate, tissue biopsy, sputum, or body fluid.34 For patients with disseminated blastomycosis, urine obtained before and after prostatic massage should be sent for fungal culture. B. dermatitidis generally takes several weeks to grow at room temperature. Once growth has occurred, highly specific and sensitive DNA probes are used to rapidly identify the mold as B. dermatitidis.

Biopsy and Cytologic Studies

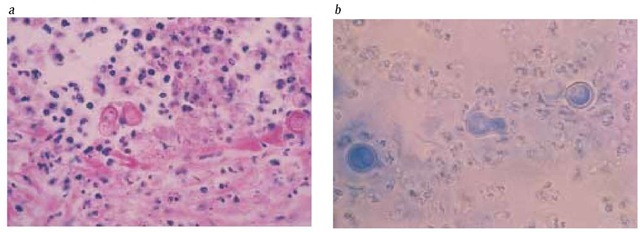

Biopsy specimens of skin lesions characteristically show pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia; when distinctive, large, thick-walled yeasts with a single broad-based bud are seen, a firm diagnosis of blastomycosis can be made before the results of cultures are known. In patients who have pulmonary lesions, the distinctive yeast forms should be sought on potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations or Papanicolaou stains performed for cyto-logic examination of sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and on lung biopsy specimens [see Figure 2].

Serologic Studies

Standard CF and ID serologic assays for blastomycosis are neither sensitive nor specific. Several different enzyme im-munoassays have been developed that enhance both specificity and sensitivity,34 but they are not currently available.

Differential diagnosis

The skin lesions of blastomycosis clinically mimic those caused by mycobacteria, especially nontuberculous mycobacte-ria; other fungal infections, especially coccidioidomycosis or paracoccidiodomycosis; mycosis fungoides; the lesions associated with bromide use; and atypical pyoderma granulosum. The histopathologic characteristics of pseudoepitheliomatous hyper-plasia occur in response to other chronic infections and to bro-moderma. Culture of biopsy material is of crucial importance in differentiating between these conditions.

Acute pulmonary blastomycosis is almost always misdiag-nosed as a bacterial or atypical pneumonia and is then treated with antibiotics.

Figure 2 Thick-walled, broad-based budding yeasts typical for B. dermatitidis are seen on biopsy material; they allow a definitive diagnosis of blastomycosis. (a) A lung biopsy specimen is stained with periodic acid-Schiff stain. The patient presented with a mass lesion in the right lower lobe and was initially thought to have lung carcinoma. (b) Purulent material was aspirated from one of numerous skin lesions in a patient with disseminated blastomycosis. Lactophenol cotton blue stain was used to prepare the slide.

Development of skin lesions is a strong clue suggesting blastomycosis. The masslike pulmonary lesion that is frequently noted with blastomycosis is usually thought to be lung cancer until biopsy results are reported. Likewise, lesions in the upper airways, which are usually firm and nodular, are frequently assumed to be squamous cell carcinoma until biopsy is performed. The clinical and radiographic signs and symptoms of patients with chronic pulmonary blastomycosis are indistinguishable from those associated with tuberculosis, histoplasmo-sis and other fungal infections, and sometimes sarcoidosis. His-topathologic studies and culture studies from biopsy material are most important in differentiating between these conditions.

Treatment

Guidelines for the treatment of blastomycosis have been published by the Mycoses Study Group under the auspices of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.33 The current recommendations are based on several multicenter, nonrandomized, open-label treatment trials and a few retrospective and prospective reports from individual institutions.17,18,35,36 There have been no trials comparing amphotericin B with azoles for the treatment of blastomycosis.

In general, patients with pulmonary or disseminated forms of blastomycosis can be treated in a similar manner. Those patients who have mild to moderate illness should be treated with an azole; patients who have severe blastomycosis, either pulmonary or disseminated, and all patients with CNS involvement should receive amphotericin B as initial therapy.

Itraconazole is the drug of choice for the treatment of mild to moderate blastomycosis.18,33 Although lesions often begin to resolve within the first month of therapy, treatment should be continued for 6 to 12 months to achieve a mycologic cure and to prevent relapse. The usual dosage is 200 mg once or twice daily for 6 to 12 months. Children with blastomycosis should be treated with itraconazole, 5 to 7 mg/kg/day. Osteoarticular involvement requires therapy for at least a year. Fluconazole is not as effective as itraconazole for blastomycosis.35,36 However, if a patient is unable to take itraconazole because of drug interactions or problems with absorption, fluconazole can be used; the dosage should be high—a total daily dosage of 400 to 800 mg given in once-daily or twice-daily doses for 6 to 12 months.

Amphotericin B should be reserved for patients who have severe blastomycosis, are immunosuppressed, or have CNS in-volvement.33 The daily dosage is 0.7 to 1.0 mg/kg until a total of 1 to 2 g has been given. An alternative and preferred approach is to first administer amphotericin B until the patient has improved and then to switch to itraconazole, 200 mg twice daily, for a total of 6 to 12 months of therapy.

Side effects, drug absorption, and drug-drug interactions are important considerations in the use of antifungal therapy [see Antifungal Therapy, below].

Prognosis

In patients with pulmonary and cutaneous manifestations of blastomycosis who undergo treatment with itraconazole, the clinical and mycologic response rates are 90% to 95%.18 If relapse occurs, a second treatment with itraconazole is generally successful. Most reported deaths from blastomycosis occur early in the course of disease in patients who present with overwhelming pneumonia and ARDS. The outcome for patients with os-teoarticular infection is good, but antifungal therapy should be given for at least a year to effect a cure.

Coccidioidomycosis

Epidemiology

The dimorphic fungus Coccidioides immitis, the cause of coccid-ioidomycosis, occupies the most specific ecological niche of the endemic mycoses commonly seen in the United States.37,38 The organism grows in the semiarid desert regions known as the Lower Sonoran Life Zone, which encompasses portions of California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and western Texas. The organism is also found in discrete areas of Central and South America.

The mycelial form of the organism produces arthroconidia, which can be widely dispersed and are highly infectious. Although persons who work outdoors are at highest risk for infection, the wide dispersal of arthroconidia ensures that most of the people who live in the endemic areas become infected before they reach adulthood. In recent years, as the allure of the sun belt has increased, there has been an increase in coccidioidomycosis in older adults. When patients with coccidioidomycosis were subjected to a case-control analysis, the greatest risk factor for the development of infection was a recent move into an area endemic for C. immitis.

Periodic outbreaks of coccidioidomycosis in the endemic area have been reported; these outbreaks are probably related to environmental cycles of rain and drought in the desert.40 Severe infection can follow massive exposure, as might occur during participation in activities such as anthropologic excavations, in which many arthroconidia are dispersed. In addition, catastrophic massive dust storms and earthquakes have been linked to the spread of C. immitis to areas far beyond those normally considered endemic for the disease.40,41

Pathogenesis

Coccidioidomycosis is acquired after the arthroconidia are inhaled into the alveoli. In the lung, the arthroconidia undergo morphologic changes that result in the formation of spherules, which are large (20 to 80 |im), thick-walled structures that become filled with huge numbers of endospores. When filled, the spherule ruptures, releasing the endospores, each of which forms a new spherule and thus propagates the infection. C. immitis does not form yeasts in tissues, as do other endemic mycoses.

The primary host defense against C. immitis is cell-mediated immunity. Neutrophils are present in most lesions but are ineffective at eradicating spherules. In hosts with deficient T cell immunity, such as patients with AIDS, the organism has the propensity to disseminate widely by the hematogenous route. Not yet elucidated is the reason for the well-known observation that dark-skinned races are at high risk for dissemination and severe infection. The highest risk appears to be among African Americans; higher but less dramatic risks for dissemination are also noted in persons from the Philippines, Native Americans, and Hispanics. Women who develop primary coccidioidomyco-sis while pregnant, especially in the third trimester, are also at increased risk for disseminated infection.

Clinical presentations

Pulmonary Coccidioidomycosis

Most persons with acute infection with coccidioidomycosis have no symptoms or have symptoms that are seen in many types of pneumonias, such as fever, nonproductive cough, chest pain, dyspnea, fatigue, myalgias, and arthralgias. Chest radiographs show a patchy pneumonitis. Erythema nodosum occurs during acute pulmonary coccidioidomycosis in as many as 25% of women and a smaller percentage of men and is a clue to the diagnosis. For most otherwise healthy patients, acute pulmonary coccidioidomycosis is a self-limited infection.

In rare cases, when exposure to the organism is extensive or the host is immunosuppressed, acute overwhelming pneumonia, characterized by high fevers, hypoxemia, and diffuse retic-ulonodular infiltrates, is seen. This is most commonly noted in patients with advanced HIV infection; in many cases, the pulmonary symptoms are merely one manifestation of widely disseminated infection.

It is estimated that fewer than 5% of patients will have residual manifestations of the acute pulmonary infection.38 Other than nodules or coccidioidomas, the most common manifestations are cavitary lesions that persist for months to years. These are generally asymptomatic, solitary, thin-walled, peripherally located lesions. Although almost half of these cavities will resolve, for some patients they can last for years and cause hemoptysis, with or without the presence of a mycetoma; they rarely rupture into the pleura. Chronic progressive coccidioidal pneumonia is rare but is more likely to occur in older patients who have COPD and diabetes mellitus; this form of coccid-ioidomycosis mimics tuberculosis or chronic cavitary histo-plasmosis clinically and radiographically.

Disseminated Coccidioidomycosis

As with other endemic mycoses, hematogenous dissemination of C. immitis is probably common and mostly asymptomatic. However, approximately one in every 200 people will develop symptoms of extrapulmonary coccidioidomycosis.37 The manifestations of extrapulmonary infection with C. immitis are protean; they may be focal and related to only one organ system that has been seeded, or they may be systemic. The sites involved most often are skin, bones, subcutaneous tissues, and the meninges. In a recent study, risk factors for disseminated disease included African-American race, low socioeconomic status, and pregnancy.42 Other studies have noted an increased risk of dissemination in patients with hematologic malignancies, those who have received an organ transplant, and, not surprisingly, those with AIDS.

The skin lesions of coccidioidomycosis are typically papular or pustular initially and then become plaquelike or verrucous; facial lesions are common. Ulceration can occur, but drainage is usually minimal. Subcutaneous abscesses are commonly noted in disseminated coccidioidomycosis. Sinus tracts form, and they may drain intermittently for years. There often is underlying osteomyelitis contiguous with these subcutaneous abscesses. Bony lesions may be single or multiple and can appear in any area of the body; vertebral involvement is particularly common. Although skin and soft tissue abscesses respond fairly well to antifungal therapy, osteomyelitis and coccidioidal arthritis are characterized by an indolent, relapsing course in spite of antifungal therapy.

C. immitis can infect any organ system, but the most dreaded complication of dissemination is meningitis. Chronic progressive meningeal infection is typically concentrated in the basilar area. Meningitis may be only one of several manifestations of severe disseminated coccidioidomycosis, or it may be the sole manifestation of coccidioidomycosis. The symptoms include headache, cranial nerve palsies, and signs of increased intracra-nial pressure. Vasculitis occurs throughout the brain in a minority of patients with coccidioidal meningitis, and spinal cord involvement at any level of the spinal cord is not uncommon. If not treated, this form of coccidioidomycosis is fatal in virtually all patients within 2 years of diagnosis. Even with treatment, which must be lifelong, the outcomes are poor.

Diagnosis

Culture

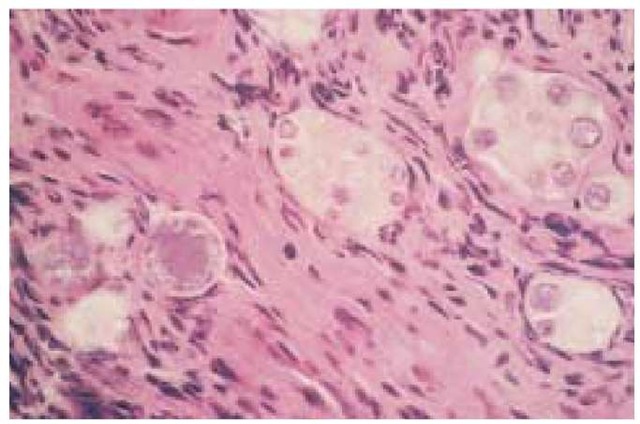

The definitive diagnostic test is growth of the organism. The mold phase of C. immitis grows within several days to a week on most laboratory media. DNA probes can identify the organism very specifically once growth has occurred. Also very helpful is histopathologic identification of the very distinctive large spherules of C. immitis in tissue biopsy, on cytologic preparations from body fluids, and even on KOH smears from sputum or from purulent material of an abscess [see Figure 3].

Serologic Studies

Serology is quite helpful in the diagnosis of various forms of coccidioidomycosis, as discussed in several excellent reviews.

For serologic tests to be as useful as possible, it is important that they be sent to a reference laboratory that is experienced in performing fungal serologic analyses. Early appearance of IgM antibodies, detected through an ID test, is helpful for the diagnosis of acute coccidioidomycosis, but this test is not always sensitive enough to detect early infection. An enzyme immunoassay that is not standardized appears to be more sensitive, but false positive results are common. For patients with chronic infections and to follow the course of infection, an IgG CF assay is generally used. A decrease in the CF antibody titer or reversion to a negative titer is associated with a good clinical response, and a stable high (> 1:16) titer or a rising titer is a poor prognostic sign. A positive CF antibody titer obtained on cerebrospinal fluid is diagnostic of coccidioidal meningitis; cultures of CSF very infrequently yield C. immitis.

Skin Tests

Skin testing with coccidioidal antigens is helpful for the diagnosis of acute infection in a person who has just entered an endemic area, but it is of little benefit for residents of endemic areas. A negative skin test result in a patient with known coccidioidomycosis implies absence of cell-mediated immunity and portends a poor prognosis.

Differential diagnosis

Coccidioidomycosis mimics many other infections. Acute pulmonary coccidioidomycosis is often diagnosed as an atypical pneumonia caused by a virus, Mycoplasma, or Chlamydia. Chronic cavitary pneumonia is radiographically similar to tuberculosis and other endemic mycoses. The diffuse pulmonary infiltrates seen in immunosuppressed patients are no different from those noted in patients with Pneumocystis carinii infection, histoplas-mosis, tuberculosis, nocardiosis, and many other infections. The importance of tissue biopsy for histopathology and culture in these settings cannot be overemphasized.

The cutaneous lesions can appear similar to those seen in patients with blastomycosis, or they can mimic squamous or basal cell carcinomas. The bone involvement associated with coccid-ioidomycosis, which is frequently accompanied by subcutaneous abscesses, is typical of that seen in patients with blastomycosis or tuberculosis. The differential diagnosis of chronic coccidioidal meningitis includes tuberculosis, other fungal infections (crypto-coccosis, histoplasmosis, and, rarely, sporotrichosis or blastomy-cosis), and sarcoidosis and other disorders of noninfectious etiology.

Treatment

The Mycoses Study Group and the Infectious Diseases Society of America have recently published guidelines for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis.44 Except for one recently completed randomized, blinded comparative trial,45 the appropriate treatment for various forms of coccidioidomycosis has been defined by open-label, nonrandomized, multicenter trials and anecdotal experience from experienced clinicians who practice in areas endemic for coccidioidomycosis.37,38,45-49 In contrast to the other endemic mycoses, either fluconazole or itraconazole can be used to treat coccidioidomycosis. A head-to-head, blinded, randomized comparison of fluconazole and itraconazole (each given in dosages of 400 mg daily for 1 year) showed no overall statistically significant difference in efficacy between the drugs.45 However, for skeletal coccidioidomycosis, itraconazole was significantly superior to fluconazole (the response rates were 70% versus 30% after 1 year of therapy).

Figure 3 Shown is a transbronchial lung biopsy specimen, stained with hematoxylin-eosin stain, from a patient with advanced HIV infection and diffuse reticulonodular pulmonary infiltrates. Large spherules (measuring 60 to 80 |im) of C. immitis in various stages of maturation are evident.

Side effects, drug absorption, and drug-drug interactions are important considerations in the use of antifungal therapy [see Antifungal Therapy, below].

Pulmonary Coccidioidomycosis

Most patients with acute pulmonary coccidioidomycosis do not require therapy with an antifungal agent, and in fact, most are not seen by a physician or the diagnosis is not made until after improvement has occurred. For patients with symptoms lasting 3 to 4 weeks who show no sign of improvement, therapy with either itraconazole, 200 mg twice daily, or fluconazole, 400 mg daily, for 3 to 6 months is recommended.44 Any patient with underlying immunosuppression, especially immunosuppres-sion associated with HIV infection, solid-organ or stem cell transplantation, or corticosteroid therapy, should be treated because the risk of dissemination is high. Pregnant women are also at risk for dissemination and should be treated. However, azoles cannot be used in pregnant women; rather, amphotericin B, which is safe in pregnancy, is required. Consideration should be given for treatment of African-American and Filipino patients because of the high risk of dissemination in these populations.

When diffuse pulmonary infiltrates are present, patients should receive amphotericin B, 0.7 mg/kg/day initially, followed by azole therapy, for a total of at least 1 year of therapy. Patients who have chronic cavitary coccidioidomycosis should receive therapy with itraconazole, 200 mg twice daily, or fluconazole, 400 mg daily for 1 to 2 years, depending on the patient’s response. However, patients with asymptomatic cavities are often observed, and treatment with an azole is begun only if the cavities increase in size or complications such as rupture into the pleural cavity have occurred or seem imminent. Surgical removal of cavities is preferred if the patient is a good operative candidate.

Disseminated Coccidioidomycosis

Disseminated coccidioidomycosis should always be treated. Patients who are seriously ill require therapy with amphotericin B, 0.7 mg/kg/day; patients with mild to moderate symptoms can be treated with an azole.44 Treatment should be given for at least 1 year; for some patients, especially those with HIV infection and African Americans, lifelong azole therapy may be required to prevent relapse.

The most difficult form of coccidioidomycosis to treat is meningitis. The preferred treatment is fluconazole; the dosage probably should be 800 mg dally, although initial studies of this therapy employed doses of only 400 mg daily.48,49 Itraconazole has been reported to be as effective as fluconazole, but experience with itraconazole is limited and most physicians prefer flu-conazole. Approximately 20% to 25% of patients will not respond to fluconazole. Amphotericin B administered by both the intravenous and the intrathecal routes is used for those in whom fluconazole therapy fails. Intrathecal amphotericin B is not well tolerated. Repeated administration of amphotericin B into the lumbar area leads to arachnoiditis, and this is an inefficient method of delivering drug to the basilar meninges. Ideally, the drug should be administered into the cistern, but most physicians cannot perform this procedure. An alternative method is delivery through an intraventricular reservoir, but this method also does not deliver drug to the basilar meninges as efficiently as intracisternal injection. Therapy must be individualized and must be given for life.49

Prognosis

Of all the endemic mycoses, infection with C. immitis is the least responsive to currently available antifungal agents. Success rates with azoles are highest in patients with soft tissue infections (approximately 70% of such patients respond after 12 months of therapy); success rates are lower in patients with chronic pulmonary infection (response rates of 50% to 60% are seen in these patients).45-47 Relapses are more common with coc-cidioidomycosis than with other endemic mycoses. For patients with chronic relapsing disease, who are often of African-American descent, lifelong azole therapy may be required. For patients with meningitis, cures are rare, and suppressive therapy must be continued indefinitely.

Sporotrichosis

Epidemiology

The dimorphic fungus Sporothrix schenckii is found worldwide. The environmental niches for the organism include sphagnum moss, decaying vegetation, hay, and soil. Infection is seen most often in persons whose vocation or avocation brings them into contact with the environment. Landscaping, rose gardening, Christmas tree farming, topiary production, baling hay, and motor vehicle accidents have all been associated with sporotri-chosis.50-52 Less commonly, pulmonary sporotrichosis results from inhalation of S. schenckii conidia from soil. Cases of sporotrichosis usually occur sporadically, but outbreaks have been described. The largest outbreak in the United States involved 84 patients in 25 states and was traced back to conifer seedlings that had been packed in sphagnum moss from Wisconsin.

S. schenckii can also be acquired through exposure to animals that are either infected or are able to passively transfer the organism from soil through scratching or biting. A variety of animals have been reported to transmit sporotrichosis, but cats with ulcerated skin lesions appear to be the most infectious. Clusters of sporotrichosis involving families and veterinarians caring for infected cats have been described.

Pathogenesis

Sporotrichosis typically develops in an otherwise healthy person who becomes exposed to the fungus while outdoors.

The typical clinical picture is that of localized cutaneous or lym-phocutaneous disease. After inoculation of S. schenckii conidia, the organism converts to the yeast form, which reproduces by budding. Strains that grow poorly at temperatures higher than 35° C tend to be found in fixed cutaneous lesions; these strains do not have the ability to spread along lymphatics, as do most strains of S. schenckii.

In patients with underlying illnesses, including alcoholism, diabetes mellitus, COPD, and HIV infection, S. schenckii can disseminate to involve osteoarticular structures, lungs, meninges, and other organs. Neutrophils and macrophages are able to ingest and kill the yeast phase of S. schenckii in the presence of non-immune human serum. A role for cell-mediated immunity as a host defense against S. schenckii is suggested by the observation that sporotrichosis is more severe in those with HIV infection.