Overview of Endemic Mycosis

The endemic mycoses (histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, and sporotrichosis) are caused by fungi that share several important characteristics but differ greatly in other respects. The fungi are all dimorphic, existing as molds in the environment and as either yeasts or spherules in tissues. Each organism occupies a different ecological niche; infection is directly related to exposure to the mycelial or mold phase of the organism in the environment. These fungi are true pathogens in that they are capable of causing infection in otherwise healthy individuals. The severity of infection is determined both by the extent of the exposure to the organism and by the immune status of the patient. Three of the four organisms (Histoplasma capsulatum, Blastomyces dermatitidis, and Coccidioides immitis) are inhaled, have the propensity to disseminate hematogenously, and are able to reactivate years later; the fourth organism, Sporothrix schenckii, usually causes primary infection after cutaneous inoculation and does not reactivate. Although many of the disease manifestations overlap, each of the four has its own distinctive characteristics.

The endemic mycoses mimic many common infections involving lungs, skin, and other organs, and frequently, the diagnosis of fungal infection is not entertained; this is especially true for patients who present outside of the areas endemic for these specific mycoses. Because of an increase in travel and leisure activities over the past several decades, patients often present with illness outside endemic areas. When faced with an elderly retiree who spends winters in Arizona and who has developed fever, headache, and visual complaints, a physician who practices in Ohio and who may have never seen coccidioidomycosis must remember that this fungal infection causes chronic meningitis. Similarly, an AIDS patient with fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and pan-cytopenia who lives in Seattle but who spent his childhood in Arkansas and has not returned there for the past 20 years may well be experiencing reactivation of disseminated histoplasmosis.

The most useful diagnostic tests differ for each of the endemic mycoses, but as a general rule, histopathologic demonstration of the fungi in biopsy specimens is the most expeditious way to make a diagnosis, especially in a severely ill patient; growth of the organism in vitro is definitive. For most patients with an endemic mycosis, treatment will be with an azole antifungal agent. For those who are severely ill, initial therapy with amphotericin B followed by consolidation therapy with an azole is standard.

A review of antifungal agents and guidelines for their use in the treatment of mycotic infections is found after the descriptions of specific manifestations of each endemic mycosis [see Antifun-gal Therapy, below].

Histoplasmosis

Epidemiology

H. capsulatum is a dimorphic fungus that every year infects hundreds of thousands of individuals in the United States. The organism is endemic in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys and Central America. Soil containing high concentrations of bird or bat guano supports the profuse growth of the mycelial phase of H. capsulatum. Exposure typically occurs as a result of activities that generate aerosols containing the organism. Although most cases are sporadic and the exact source of exposure is unknown, many point-source outbreaks have been well described in association with disruption of soil; the cleaning of attics, bridges, or barns; tearing down old structures laden with guano; and spelunking.1-3 Massive outbreaks of infection with H. capsulatum occurred when urban demolition exposed hundreds of thousands of people to the organism.1 Infection is very common in the endemic area, most persons having been infected before adulthood.

Pathogenesis

During the mycelial phase of the organism’s life cycle, the mi-croconidia are inhaled into the alveoli, causing a localized pulmonary infection. Neutrophils and macrophages phagocytize the organism, which converts to the yeast phase; the organism is then able to survive and travel within the macrophage. Spread to the hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes ensues, and hematoge-nous dissemination subsequently occurs throughout the reticu-loendothelial system before specific immunity has developed. After several weeks, cell-mediated immunity that is specific for H. capsulatum activates macrophages, which then kill the organism.4 Of all the human mycoses, histoplasmosis exemplifies best the pivotal importance of the cell-mediated immune system. The corollary of this observation is that most patients with severe infection are those with cellular immune deficiencies.

The extent of disease is determined by the number of conidia that are inhaled and the immune response of the host. A healthy individual may develop severe life-threatening pulmonary infection if a large number of conidia are inhaled. This might occur during demolition or renovation of an old building or as a result of spelunking in a heavily infested cave. Conversely, a small inoculum can cause severe pulmonary infection or progress to acute symptomatic disseminated histoplasmosis in a patient with advanced HIV infection whose cell-mediated immune system is unable to contain the organism.

Most persons who have been infected experience asymptomatic dissemination; only rarely will this lead to symptomatic acute or chronic disseminated histoplasmosis. However, by virtue of this dissemination, latent infection can persist for a lifetime. Reactivation of quiescent infection can occur years later if immunosuppression occurs.5 Reinfection has also been documented, though rarely, in persons previously known to have had histoplasmosis. Such reinfection almost always occurs in the setting of exposure to a heavy inoculum of H. capsulatum conidia.

Clinical presentations

Pulmonary Histoplasmosis

Infection is asymptomatic in the vast majority of persons who have been infected with H. capsulatum. Most patients who have symptomatic pulmonary infection will have a self-limited illness characterized by fever, chills, and cough that is usually nonproductive; such infection is often associated with anterior chest discomfort, myalgias, arthralgias, and fatigue. A patchy lobar or multilobar nodular infiltrate is noted on chest radiography.6 The diagnosis is usually not made in individual cases until the patient fails to respond to several courses of antibiotics given for atypical pneumonia.

The diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis is more easily made when the patient has been involved in an outbreak.2 A careful history of the patient’s activities as well as the patient’s colleagues’ activities—especially if the history reveals participation in outdoor activities, activities around a demolition site, or spelunking several weeks before the onset of symptoms—may point to histoplasmosis. High spiking fever, prostration, dyspnea, and cough are prominent in severe cases in which the number of conidia inhaled is large. Diffuse nodular infiltrates are noted on the chest radiograph, and development of the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) can ensue.

In patients with cell-mediated immune deficiencies, including those who have advanced HIV infection, those with a hemato-logic malignancy, those who have received a transplant, and those who are receiving immunosuppressive medications, pulmonary infection is more severe than in otherwise healthy patients. Although pulmonary infection may be the only manifestation of histoplasmosis, in most immunosuppressed patients, pulmonary involvement is merely one component of widespread dissemination.7 Prostration, fever, chills, marked dyspnea, and hypoxemia are prominent, and chest radiographs show diffuse infiltrates.

Chronic cavitary pulmonary histoplasmosis is a progressive, fatal form of histoplasmosis that usually develops in older patients who have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Typical symptoms include fever, fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, cough that is productive of purulent sputum, and hemoptysis.8,9 On chest radiography, infiltrates can be either unilateral or bilateral and are almost always located in the upper lobes. Cavities may be multiple and are frequently quite large; extensive fibrosis occurs in the lower lobes.

Disseminated Histoplasmosis

Hematogenous dissemination typically occurs in immuno-suppressed patients and young children early in the course of infection with H. capsulatum. Patients who have HIV infection and whose CD4+ T cell counts are less than 150 cells/mm3 are at great risk for acquiring histoplasmosis, which almost always presents as disseminated infection. Symptoms and signs of acute disseminated histoplasmosis include chills, fever, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, dyspnea, hepatosplenomegaly, and skin and mucous membrane lesions. Pancytopenia, diffuse pulmonary infiltrates seen on chest radiographs, and blood cultures that yield H. capsulatum are common.7,10 Adrenal insufficiency may also be present.

A chronic progressive disseminated form of histoplasmosis that occurs mostly in middle-aged to elderly men who have no known immunosuppressive illness is characterized by fever, night sweats, weight loss, and fatigue.11 Patients appear chronically ill and frequently have hepatosplenomegaly, mucocutaneous ulcer-ations, and signs of adrenal insufficiency. Typical findings include an increase in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, an elevation in the alkaline phosphatase level, pancytopenia, and diffuse pulmonary infiltrates seen on chest radiograph. If not diagnosed and treated appropriately, this form of histoplasmosis is fatal.

Diagnosis

Culture

The definitive diagnostic test for histoplasmosis is growth of H. capsulatum in culture, which, unfortunately, may take as long as 6 weeks.5 Sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, or tissue biopsy material should be sent to the laboratory for culture. For those patients who have evidence of dissemination, cultures of blood are useful. The best yield is with the lysis-centrifugation system (Isolator aerobic blood culture system, Wampole Laboratories). The laboratory should be informed that pulmonary histoplasmosis is a diagnostic consideration, so that a special medium that decreases the growth of commensal fungi, such as Candida, can be used for the culture of pulmonary samples. As soon as growth of a mold has been detected, a DNA probe specific for H. capsulatum confirms the identity of the organism.

Serologic Studies

In contrast to several other endemic mycoses, serology plays an important adjunctive role in the diagnosis of histoplasmosis.12 Both complement fixation (CF) and immunodiffusion (ID) tests are available. ID is more specific than CF (> 95% specificity versus 85% to 90%); both are only modestly sensitive (75% to 85% sensitivity). False negative serologic test results occur in im-munosuppressed patients who cannot mount an antibody response. However, most patients with pulmonary histoplasmosis are not immunosuppressed, and thus, in this group, antibody tests are helpful.

Patients with chronic cavitary pulmonary histoplasmosis almost always have an elevated CF antibody titer (> 1:32), and either an M precipitin band or both H and M precipitin bands are seen on ID in these patients. In a patient with acute pneumonia, a documented fourfold increase in CF titer or the appearance of an M precipitin band on ID establishes the diagnosis of histoplasmo-sis. Serologic tests are less definitive in patients with mediastinal lymphadenopathy and should always be confirmed by tissue biopsy. False positive test results, especially false positive results on CF, occur in patients with lymphoma, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and other fungal infections, all of which may present as mediasti-nal masses. In most patients with the chronic disseminated form of histoplasmosis, both precipitin and CF antibodies are present.

Antigen Tests

Enzyme immunoassays for the detection of H. capsulatum polysaccharide antigen in urine and serum are extremely helpful in AIDS patients who have disseminated infection and a large fungal burden.13,14 They are less useful for patients with pulmonary histoplasmosis; antigen is detected in only about 20% of patients with pulmonary histoplasmosis. Cross-reactivity occurs in a small number of patients with blastomycosis, paracoccid-ioidomycosis, and penicilliosis.

Tissue Biopsy

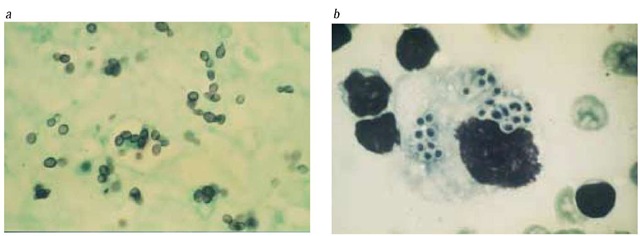

For an acutely ill person, evidence of H. capsulatum on tissue biopsy allows the physician to make the diagnosis of histoplas-mosis in a timely fashion.5 The organisms appear as distinctive, fairly uniformly shaped, oval budding yeasts 2 to 4 |im in diameter. Tissue biopsy is most useful for the diagnosis of disseminated disease; bone marrow, liver, and mucocutaneous lesions reveal many organisms [see Figure I]. For most patients with acute pulmonary histoplasmosis, biopsy is not indicated unless the patient is severely ill. For patients with chronic pulmonary histoplasmo-sis or granulomatous mediastinitis, biopsy of lung or lymph nodes may reveal the organism. Routine hematoxylin-eosin staining will not show the tiny H. capsulatum yeasts; biopsy material must be stained with methenamine-silver stain, periodic acid-Schiff stain, or both. In contrast to larger yeasts, such as B. dermatitidis, it is extremely unusual to find H. capsulatum on cytologic examination of sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

Figure 1 Shown are biopsy samples from an elderly man with chronic progressive disseminated histoplasmosis. (a) Tongue ulcer stained with methenamine-silver stain shows several budding yeast forms measuring 2 to 4 |im. (b) A smear from a lung biopsy sample, which is stained with Giemsa stain, shows small intracellular yeasts inside a macrophage.

Skin Tests

Skin tests with histoplasmin antigen are not useful for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis in individual patients. In the endemic area, as many as 85% of adults have positive results on skin testing because of previous exposure to the organism; cross-reactions occur in those with other fungal infections, especially blas-tomycosis; and negative test results occur frequently in patients who have severe infection.

Differential diagnosis

Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis is most difficult to differentiate from acute pulmonary blastomycosis. The clinical and radi-ographic findings of these two diseases are similar, the regions in which these diseases are endemic overlap, and the CF antibody tests for the two organisms show cross-reactivity. For either disease, culture of the causative organism from sputum is diagnosti-cally definitive. However, results of sputum cultures are often negative for patients with acute pneumonia caused by either fungus. Treatment, fortunately, is the same for the two diseases. Atypical pneumonias caused by Mycoplasma, Legionella, and Chlamydia are included in the differential diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis. Hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy, which is very common with histoplasmosis, is uncommon in patients with atypical pneumonia caused by these other organisms.

Chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis mimics tuberculosis in regard to symptoms, signs, and radiographic findings. Other chronic fungal pneumonias, especially blastomycosis and sporotrichosis, and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections also must be differentiated from this form of histoplasmosis. Sputum culture and serology are most useful in differentiating these infections.

Patients with acute disseminated histoplasmosis can present with a sepsis syndrome associated with ARDS and disseminated intravascular coagulation that is indistinguishable from sepsis of any bacterial or viral etiology. Helpful findings supporting the diagnosis of histoplasmosis are pancytopenia, diffuse nodular pulmonary infiltrates, and hepatosplenomegaly; the hematology laboratory may make the diagnosis when they find small yeasts inside white cells on the peripheral smear. In AIDS patients, the main infections that must be excluded are those caused by cy-tomegalovirus, Mycobacterium avium complex, and M. tuberculosis. Biopsy of involved tissues should be performed as soon as possible to help differentiate between these conditions. Culture of blood by means of lysis-centrifugation (Isolator system) for fungus and Mycobacteria and use of urinary antigen testing for H. capsulatum are very helpful diagnostic tests in this circumstance.

Patients with chronic disseminated histoplasmosis usually present with fever of unknown origin. The disease that mimics histoplasmosis most closely is miliary tuberculosis; lymphoma, brucellosis, and sarcoidosis also must be excluded. Serology is helpful, but histopathologic evidence of yeasts in tissue granulo-mas and confirmatory culture of the organism from bone marrow, mucous membrane lesions, or liver are definitive. It should be emphasized that the diagnosis of sarcoidosis requires firm evidence that the patient does not have histoplasmosis or tuberculosis; corticosteroid use for the treatment of suspected sarcoido-sis in patients who in fact have histoplasmosis frequently leads to defervescence for a short period, followed by further worsening of the infection.15

Treatment

Guidelines for the treatment of histoplasmosis have recently been published by the Mycoses Study Group and the Infectious Diseases Society of America.16 Efficacy has been defined primarily by open-label trials in patients with and without AIDS and through anecdotal experience17-22; there are no studies that directly compare azoles with amphotericin B. The only blinded, randomized treatment trial studied liposomal amphotericin B versus amphotericin B deoxycholate in a very restricted patient population: AIDS patients with severe disseminated histoplasmosis.23 In spite of the lack of controlled treatment trials, it is clear that for the treatment of most patients with histoplasmosis, itraconazole is the drug of choice.18-20 Fluconazole should be considered a second-line agent; primary response rates are lower for fluconazole in patients with and without AIDS, and relapse rates for AIDS patients receiving fluconazole are higher than those noted in previous studies with itraconazole.21,22 If a patient does not tolerate itraconazole, fluconazole can be used, but the dosage should be 400 to 800 mg daily. Side effects, drug absorption, and drug-drug interactions are important considerations in antifungal therapy,particularly in long-term regimens such as those frequently required for AIDS patients [see Antifungal Therapy, below].

Pulmonary Histoplasmosis

Treatment recommendations are based on the type of histo-plasmosis and the immune status of the host.16 Treatment is generally not recommended for patients with acute pulmonary histoplasmosis; in fact, the diagnosis is often not made until after the patient’s symptoms have resolved. However, if the patient remains symptomatic after 4 weeks, therapy with itraconazole, 200 mg daily for 6 to 12 weeks, is recommended. Children with acute pulmonary histoplasmosis should be treated with itra-conazole, 5 to 7 mg/kg/day.

Although pneumonia resolves without treatment in most patients with acute outbreak-related histoplasmosis, those with severe infection should receive treatment. Immunosuppressed patients with acute pulmonary histoplasmosis should always be treated. Initial therapy should be administration of amphotericin B, 0.7 mg/kg/day. After a favorable response is noted, which usually occurs quite soon after initiation of therapy, therapy can be changed to oral itraconazole. Treatment should continue until the infiltrate has resolved.

Antifungal therapy is required for all patients with chronic pulmonary histoplasmosis.8,16 Itraconazole, 200 mg once or twice daily for 12 to 24 months, is the treatment of choice. Even with appropriate antifungal therapy, outcome is poor.

Disseminated Histoplasmosis

All patients with symptomatic disseminated histoplasmosis should receive antifungal therapy.11,16 Patients with acute disseminated disease who have only mild to moderate symptoms and most patients with chronic progressive disseminated histoplas-mosis should be treated with itraconazole, 200 mg twice dally; this recommendation applies both to patients with AIDS and to those who do not have AIDS. For patients who do not have AIDS, a total of 12 months of therapy is usually adequate, but the length of therapy will be determined by the patient’s clinical course; this is especially true for patients with chronic progressive disease. Patients who have AIDS should initially receive itraconazole twice daily for 12 weeks; after that period, they should receive a maintenance course of long-term suppressive therapy with itraconazole, 200 mg daily.20

Young infants, who frequently have overwhelming infection, and immunosuppressed patients with moderately severe to severe symptoms should be treated initially with amphotericin B, 0.7 to 1.0 mg/kg/day. For most adults, therapy can be changed to itraconazole after they become afebrile and are able to take oral medications. Infants should receive a full course of ampho-tericin B because experience with itraconazole is limited in this population group. When therapy is with amphotericin B deoxy-cholate only, the total dose should be 35 mg/kg.

In a blinded, randomized clinical trial, liposomal amphotericin B, 3 mg/kg/day, was found to be superior to amphotericin B de-oxycholate, 0.7 mg/kg/day, for initial treatment of AIDS patients who had severe disseminated histoplasmosis. In this study, the 51 patients receiving liposomal amphotericin B became afebrile sooner than the 22 receiving amphotericin B deoxycholate (P = 0.01); in addition, mortality was decreased and toxicity was lessened in the liposomal amphotericin B arm.23 However, it is not clear whether these results should affect clinical decision making regarding the treatment of disseminated histoplasmosis in patients who do not have AIDS. The main drawback to the use of the liposomal formulation of amphotericin B is that it is extremely costly in comparison with the standard formulation.

Complications

Granulomatous mediastinitis is an uncommon complication of pulmonary histoplasmosis in which lymphadenopathy persists for months.5 The enlarged nodes can erode into the esophagus; can lead to the formation of tracheoesophageal fistulas; and can cause traction diverticula. Chest radiography and CT scanning reveal enlarged hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes; necrosis and calcium deposition in the nodes are commonly noted on CT scan. Mediastinoscopy and biopsy reveal caseous material, which may contain a few yeastlike organisms typical of H. capsulatum. In most patients, the disease follows a self-limited, although protracted, course, and patients do not develop fibrosing mediastinitis. Patients may benefit from itra-conazole, 200 mg twice daily, but there are no clinical trials proving efficacy.16

Fibrosing mediastinitis is a rare complication of pulmonary histoplasmosis in which an excessive amount of fibrosis develops in the mediastinal lymph nodes in response to infection.24,25 The exuberant fibrous tissue entraps the great vessels, causing heart failure, pulmonary emboli, and superior vena cava syndrome. Odynophagia, dyspnea, cough, wheezing, and hemoptysis are commonly noted. There is no effective therapy for this progressive disease.

Pericarditis is a self-limited illness that occurs as an inflammatory response to acute pulmonary histoplasmosis.5 Pleural effusions and mediastinal lymphadenopathy are commonly noted with pericarditis. The pericardial fluid is exudative. Drainage is required if tamponade occurs, but this is rare. Pericarditis should be treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; cortico-steroids should be used for severe cases. Antifungal agents should not be used.16 The long-term outcome is excellent; only rarely has constrictive pericarditis occurred.

Prognosis

Most patients with histoplasmosis respond quite well to anti-fungal agents. Even patients with advanced AIDS respond quickly and completely to therapy and continue to do well as long as they receive suppressive therapy with an azole. Patients with chronic progressive disseminated histoplasmosis usually experience a return to their baseline function, but it often takes months for this to occur. The patients who do poorly are those whose underlying illness precludes a return to normal function. For example, patients with chronic cavitary pulmonary histo-plasmosis frequently have progressive respiratory insufficiency because of their severe underlying emphysema and the fibrosis caused by the fungal infection.

Blastomycosis

Epidemiology

Although the dimorphic fungus B. dermatitidis is present in many diverse geographic areas worldwide, most cases of blasto-mycosis are reported from the south central and north central United States.26 The endemic area for blastomycosis overlaps that for histoplasmosis but extends further north into Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the southern portions of the Canadian provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. Most cases are reported from Arkansas, Mississippi, and Kentucky.

The ecology of B. dermatitidis is not as well understood as that of the other endemic mycoses. It is assumed that the natural niche is soil, but the yield of soil cultures is quite low. Most cases occur sporadically, but several well-described outbreaks have helped define the presumed natural habitat.27,28 The largest outbreak to date involved 95 students in northern Wisconsin who camped along a beaver pond and explored a beaver lodge.27 Decomposed wood on the pond bank and samples from the lodge yielded B. dermatitidis.

Most, but certainly not all, patients who develop blastomyco-sis are men who have an outdoor occupation or hobby. Cases have been described in hunters and their dogs; in these cases, it is presumed that the hunters and their dogs were exposed to the same environmental source. For most sporadic cases, the source of exposure to the fungus is unknown.

Pathogenesis

Most patients with blastomycosis have no underlying illnesses, but the disease is more severe in immunosuppressed patients.29 Blastomycosis is acquired by inhaling the conidia of B. dermatitidis into the alveoli. The organisms change to the yeast form in the lungs and then reproduce by budding. The immune response to B. dermatitidis appears to include both neutrophils and cell-mediated immune mechanisms involving T cells and macrophages.

Even though a major clinical manifestation of blastomycosis is cutaneous lesions, blastomycosis is only very rarely spread through inoculation. Examples of such cases include accidental inoculation in laboratory workers, conjugal inoculation from a genital lesion, and inoculation from the bite of an infected dog. The organism travels to the skin and other common target organs, including osteoarticular structures and the genitourinary tract, by the hematogenous route. Most persons infected with B. dermatitidis are asymptomatic or have mild pulmonary symptoms. Hematogenous dissemination occurs without clinical manifestations, and only later do patients present with skin lesions in the absence of other obvious organ involvement.