Epidemiology and pathogenesis

In the United States, alopecia areata affects 1.7% of the population younger than 50 years.25 Some 70% to 75% of cases are not associated with any other disease. In these patients, alopecia areata often starts in the 20s and 30s, although it can occur at any age. In only about 6% of these patients with alopecia areata does the disease progress to total loss of scalp hair. Even total alopecia can reverse itself.

Alopecia areata is currently regarded as an autoimmune disease. A positive family history in 20% of alopecia areata patients indicates a genetic predisposition to this disease. Certain HLA groups have been associated with mild or severe cases of alopecia areata.26 Although the exact cause is unknown, many researchers presume that an infectious agent such as a virus is the offending agent. Stress, seasonal factors, and infection are among the trigger factors for active episodes of hair loss.

Some 5% of alopecia areata cases—usually those occurring in middle-aged patients—are associated with autoimmune disease, either in the patient or in the patient’s family. Some 10% of these patients will experience loss of all scalp hair in the course of the disorder. Approximately 20% to 25% of cases—often those occurring in childhood—may be associated with atopic disease (e.g., hay fever, asthma, or eczema). The incidence of complete scalp hair loss is much higher in these patients.

Despite its long course, often recurring over many years, the prognosis of alopecia areata is often favorable. Most patients will regrow hair at one time or another. In cases of extensive alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, and alopecia universalis, however, hair loss may be permanent.

Diagnosis

Active alopecia areata is characterized by a spreading, annular area of hair loss; a smooth, depressed area of scalp that is slick to the touch is surrounded by hairs that often include so-called exclamation-point hairs (i.e., broken hairs 3 to 4 mm long, usually with an expanded tip and a telogen bulb). These hairs are not always seen but are diagnostic when present. They delineate the active spreading margin of alopecia areata. The bald patches generally affect the scalp but can also involve eyebrows, eyelashes, beard hair, and body hair. Spontaneous regrowth is common.

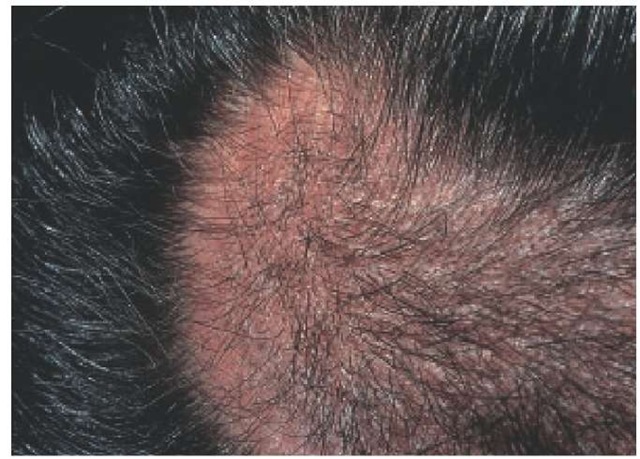

This condition is extremely unpredictable, often fluctuating without any obvious reason. However, seasonal outbreaks are noted in many patients. The initial patch may enlarge, or additional patches may develop and become confluent [see Figure 5]. The condition can progress to large irregular areas of baldness. In severe cases, patients lose all scalp hair or all body hair.

Ophiasis is a chronic and difficult to treat form of alopecia areata in which a band of baldness circles the scalp, very often around the inferior margin. This slowly extending lesion is often present for several years before any regrowth occurs. Permanent hair loss may result in some areas.

Treatment

The treatment of alopecia areata depends on the severity of the disease.27 Small patches of alopecia areata often regrow hair without treatment. If not, they usually respond to medium- or high-potency topical corticosteroids or to intralesional injections of triamcinolone acetonide at a concentration of 5 mg/ml.

In more severe cases, intralesional corticosteroids may be tried; however, these may not be feasible in extensive hair loss. Daily, short-contact topical therapy with 0.25% to 1% anthralin cream for up to an hour at a time may help and is suitable for children and adults. Psoralen and ultraviolet A (PUVA) therapy has also been used with some success.

Topical 5% minoxidil can be tried to speed hair regrowth and lengthen existing hairs. Minoxidil has no effect on the course of the disease but may improve hair coverage. It has few side effects and is often used in older children; however, the FDA has approved minoxidil for use only in persons 18 years of age and older. Systemic steroids are effective; however, they have shown a potential for side effects and do not prevent future recurrences.28 Prednisone (20 to 40 mg daily in the morning for 1 or 2 months followed by slow tapering) has controlled the disease in adults; a change to alternate-day therapy is advisable whenever possible.

Topical immunotherapy with the sensitizing chemical diphen-cyprone has been used in some centers; it has a response rate comparable to that of systemic corticosteroids.29 Success with this treatment usually requires supervision in a specialized clinic.

Figure 5 Circumscribed patches of hair loss are present in alopecia areata.

Sulfasalazine has been reported to have a 23% success rate in the treatment of severe alopecia areata.30 Other immunosuppressive drugs, such as oral cyclosporine, have been used experimentally. Such therapies are risky and expensive, however, and have not been approved in the United States for alopecia areata.

Traumatic alopecia

Traumatic alopecia may be caused by a variety of physical or chemical injuries to the hair and scalp. These injuries may be deliberate or accidental, inflicted by self or others, and acute or repetitive. The cause may be obvious or unclear.31 Potential causes include trichotillomania, habit tics, pruritic dermatoses, traction, pressure and friction, heat, radiation, and chemicals. In most cases of traumatic alopecia, management is removal of the underlying cause. In areas with permanent damage, hair transplantation may be necessary.

Trichotillomania

Trichotillomania is a compulsion to pull out one’s hair. It is characterized by an increasing sense of tension before, and a sense of relief after, the hair is pulled. Trichotillomania is now classified as a specific disorder of impulse control.31,32 It is more common in children, in whom it is often caused by insecurity re-sulting from sibling rivalry, lack of attention, divorce of parents, learning disabilities, or unhappiness or teasing at school. In adolescents and adults, trichotillomania may be accompanied by mood disorders, anxiety disorders, or mental retardation and is often harder to treat than in children.

Figure 6 Irregular, broken-off hairs are seen in trichotillomania.

The diagnosis is based on the presence of irregular, broken-off hairs in patches on the scalp [see Figure 6]. The hairs are irregular in length because they are broken off at different times. The scalp itself is normal. Occasionally, biopsies are necessary to confirm the diagnosis. The best treatment is to explain cause and remedy to the patient in a nonconfrontational manner; usually, reassurance and understanding go a long way in the treatment of this condition. In more difficult cases, psychiatric consultation may be indicated.33 If habit tics or head rolling and banging are found to be causing traumatic hair loss, those behaviors should be treated.

Other causes of traumatic alopecia

Pruritic Dermatoses

Pruritic dermatoses such as acne necrotica, folliculitis, lichen simplex chronicus, pediculosis capitis, prurigo nodularis, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and neurotic excoriations can lead to hair loss from excoriation. They need to be identified and treated.

Traction Alopecia and Loose Anagen Syndrome

Traction alopecia may be acute (caused by accidental or deliberate avulsion of the scalp) or may arise from a familial condition, the loose anagen syndrome. Common causes of traction alopecia are excessive brushing and combing; backcombing and pulling the hair into braids, cornrows, and ponytails; weaving; and application of rollers.31

Loose anagen syndrome is usually seen in fair-haired children 2 to 5 years of age.34 It often presents as patchy hair loss following an incident of hair tugging. Prompt hair regrowth is the rule. The condition becomes asymptomatic with gentle hair care. Diagnosis is made on the basis of positive hair pull tests showing many anagen hairs.

Alopecia Caused by Pressure and Friction

Prolonged pressure on a localized area of the scalp in immobilized neonates or patients under anesthesia, in coma, or with debilitating illness may result in ischemia leading to pressure alopecia. The hair usually regrows with time, but if the damage is severe, permanent hair loss and scarring may result.31 Alopecia caused by friction from vigorous massage has been described but is easily remedied.

Alopecia Caused by Heat, Radiation, and Chemicals

Excessive heat from hot oils and pomades, hot combs, and hot rollers is a common cause of chronic hair loss. Overheated hair dryers frequently cause the fluid droplets in wet hair shafts to expand, leading to the formation of bubble hairs.35 These brittle hairs are a frequent cause of follicle damage. The source of the overheating needs to be identified and removed.

Radiation dermatitis can cause hair loss. Permanent scarring alopecia is still seen in patients who were overtreated with x-rays for tinea capitis before oral antifungal agents became available.

Many chemicals, such as hair dyes, moisturizers, oils and pomades, permanent waves, relaxers and straighteners, setting lotions, certain cationic and detergent shampoos, and saltwater, are possible causes of hair loss.36 A careful history of hair care and grooming is needed to uncover these causes.

Cicatricial Alopecia

Cicatricial alopecia results from permanent scarring of the hair follicles. It may be widespread or localized and is sometimes difficult to identify. The causes of cicatricial alopecia may be primary or secondary.37 It can result from hereditary or congenital conditions, infections, injuries, neoplasms, and dermatoses [see Table 4].

Diagnosis

On clinical examination, scarring is detected by the absence of follicular orifices and a pearly or scarred appearance of the skin. The scar may be depressed or hypertrophic. Associated lesions such as folliculitis, follicular plugs, scales, and telangiectasias may be found, along with broken, twisted, or easily extractable hairs. Other lesions may be present on skin or mucous membranes. If the disease is active, a specific diagnosis may be possible; but in an inactive case, the initial cause is often inapparent.

Clinical Variants

The common variants of primary cicatricial alopecia of the scalp include discoid lupus erythematosus, lichen planopilaris, folliculitis decalvans, and pseudopelade.38,39 The end phases of these conditions are similar; they are characterized by a lack of pores and by inflammation in white, scarred areas. For an accurate diagnosis, an early biopsy from an area of activity might show the identifying pathology. In the final scarring stage, it is usually not possible to identify the original cause.

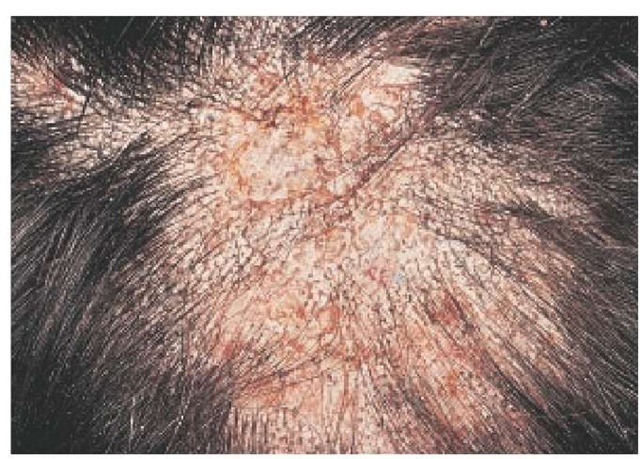

Discoid lupus erythematosus Lesions are often itchy at onset and lead to erythema, scaling, telangiectasia, follicular spines, and atrophy [see Figure 7]. They often occur centrally in bare patches of scarring with an inactive border [see 15:IV Systemic Lupus Erythematosus].

Lichen planopilaris Central scarring characterizes these lesions. The condition generally starts with bare, white patches that bud out from one another like pseudopods. Prominent follicular hyperkeratosis is present around the residual terminal hairs at the edges of the lesion, and varying degrees of erythema, scaling, and telangiectasia may occur. Itching may be present.

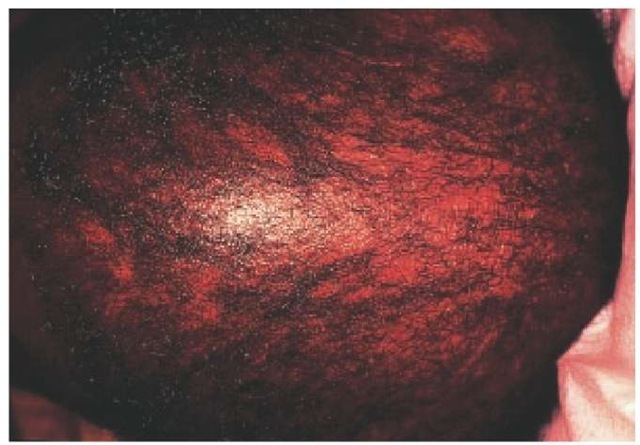

Folliculitis decalvans Crops of follicular pustules surrounding multiple, slowly expanding, and round or oval areas of alopecia characterize this condition. It may involve large areas of the skin. Secondary infection may be severe, with crusting and oozing. Eventually this condition gradually loses activity and looks like other forms of chronic cicatricial alopecia.

Pseudopelade (nonspecific cicatricial alopecia) The majority of cases classified as pseudopelade are in fact cases of nonspecific cicatricial alopecia in which the initial cause has not been established. In general, there is an insidious spread of a scarring process, which is apparently noninflammatory. It often involves the crown and occurs mainly in middle-aged women. It may represent the final common pathway of various causes, such as lichen planopilaris in particular or discoid lupus erythematosus. It is characterized by patchy areas of alopecia with irregular extensions. The affected skin is smooth, white, and devoid of erythema, scaling, or pores, causing the so-called footprints in the snow. The course is variable and may last for a few years or several decades.

The original cases were described as a specific entity in the late 19 th century and were reported as pseudopelade of Brocq.

Table 4 Causes of Cicatricial Alopecia46

|

Dermatoses |

Cicatricial pemphigoid, dermatomyositis, folliculitis decalvans, lichen planopilaris, lupus erythematosus, neurotic excoriations, pseudopelade, scleroderma |

|

Hereditary and congenital disorders |

Aplasia cutis, epidermal nevi, epidermoly-sis bullosa |

|

Infections Bacterial |

Acne keloidalis, dissecting cellulitis, folli-culitis, syphilis |

|

Fungal |

Favus (tinea capitis), kerion, mycetoma |

|

Protozoan |

Leishmaniasis |

|

Viral |

Herpes zoster, varicella |

|

Injuries |

Burns, mechanical trauma, radiodermatitis |

|

Neoplasms |

Angiosarcoma, basal cell epithelioma, lym-phoma, melanoma, metastatic tumors, squamous cell carcinoma |

This eponym is rarely used nowadays except perhaps for a small cohort of cases with no inflammatory phase at all, particularly occurring in children. Most cases of so-called pseudopelade of Brocq are explainable as an end stage of lichen planopilaris or other causes.37

Treatment

Treatment depends on the level of activity of the underlying disease. Discoid lupus erythematosus and lichen planopilaris may respond to topical, intralesional, or systemic steroids or oral chlo-roquine therapy. Topical minoxidil is sometimes helpful in re-growing any surviving hairs, which may be normal, dystrophic, or in a resting stage. The application of a 2% or 5% solution twice daily should be tried for at least a year on scarred areas that show some hair. Folliculitis decalvans may respond to treatment with long-term antibiotics such as tetracycline (500 mg), minocycline (100 mg), erythromycin (250 mg), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxa-zole (regular strength), or rifampin (300 mg, with regular-strength trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, given twice daily for at least 3 months). When the conditions have burned themselves out, either scalp reduction or hair transplants may be helpful.

Figure 7 Atrophic scarring with erythema, scaling, telangiectasia, and follicular spines are characteristic of discoid lupus erythematosus.

Figure 8 In endothrix tinea capitis, black dots represent brittle, infected hairs snapped off flush with the scalp.

Figure 9 The characteristic irregular, so-called moth-eaten diffuse alopecia caused by syphilis is seen here.

Miscellaneous Causes of Hair Loss

As mentioned earlier, less common causes of hair loss include infections (e.g., tinea capitis),40 infestations, hair shaft abnormalities, hereditary and congenital conditions, and various der-matoses involving the scalp.

In the United States, tinea capitis is now largely caused by Tricho-phyton tonsurans, an endothrix that infects the inside of the hair shaft. This makes the shaft brittle, which causes it to snap off flush with the skin, leaving a characteristic black dot of hair [see Figure 8]. The clinical diagnosis depends on this finding of black dots in patchy areas of hair loss. Removing the black dot with a small scalpel blade and dissolving it in potassium hydroxide (KOH) should reveal many spores that were packed inside the affected hair shaft. Ectothrix ringworm caused by Microsporum canis and M. audouinii is much less common; it can usually be di-agnosed by Wood’s light or by a finding of fungal spores around the hair shaft with KOH. Suitable oral antifungal treatments include griseofulvin, itraconazole, terbinafine, and fluconazole.

Secondary syphilis can cause a somewhat nondescript, moth-eaten type of diffuse alopecia [see Figure 9]. In such cases, a routine serologic test for syphilis is indicated.

Scalp lice should always be sought in cases of hair loss accompanied by pruritus. Lice are most likely to be found around and behind the ears and on the nape of the neck. Lymphadenopathy may also be present. Suitable treatment with permethrin shampoo or 0.5% malathion can be given.

Hair shaft abnormalities frequently present as broken-off hairs. Structural abnormalities of the hair shaft include fractures, irregularities, coiling and twisting, and extraneous matter.41,42

There are many different types of congenital and inherited hair loss.43 These include congenital hypotrichosis with or without associated defects, congenital triangular alopecia, and many ectodermal dysplasias that affect the hair, teeth, nails, and sweat glands. One major form of congenital hypotrichosis is the Marie-Unna syndrome, which affects large families that have a dominant gene.44 Minor forms of hypotrichosis can occur in patients with other hereditary syndromes and chromosomal abnormalities. In most of these conditions, a reduction of hair follicles accounts for the hair loss. Some patients have surviving hairs that are often in telogen and may benefit from topical minoxidil.