The chlamydiae are obligate intracellular bacteria that produce a wide variety of infections in many mammalian and avian species.1 Three species of Chlamydia infect humans: C. trachomatis, C. psittaci, and C. pneumoniae [see Table 1]. C. trachomatis is exclusively a human pathogen and is transmitted from person to person via sexual contact, perinatal transmission, or close contact in households. C. trachomatis causes trachoma in arid developing parts of the world and is a major cause of sexually transmitted and perinatal infections worldwide. In the United States, C. trachomatis infection is the most common reportable infectious disease.2 C. psittaci, in contrast, is more widely distributed in nature, producing genital, conjunctival, intestinal, or respiratory infections in many avian and mammalian spe-cies.3 Humans are occasionally infected by avian strains after contact with infected birds, incurring a pneumonitis or a systemic infection termed psittacosis.

C. pneumoniae, the third chlamydial species that infects humans, was identified and characterized in the 1980s.4 It is a fastidious organism that produces upper respiratory tract infection and pneumonitis in both children and adults.5 Recent studies have also linked C. pneumoniae infection to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and perhaps to other illnesses, such as asthma and sarcoidosis.6 Transmission is believed to occur via aerosol droplets; no animal reservoir has been identified.

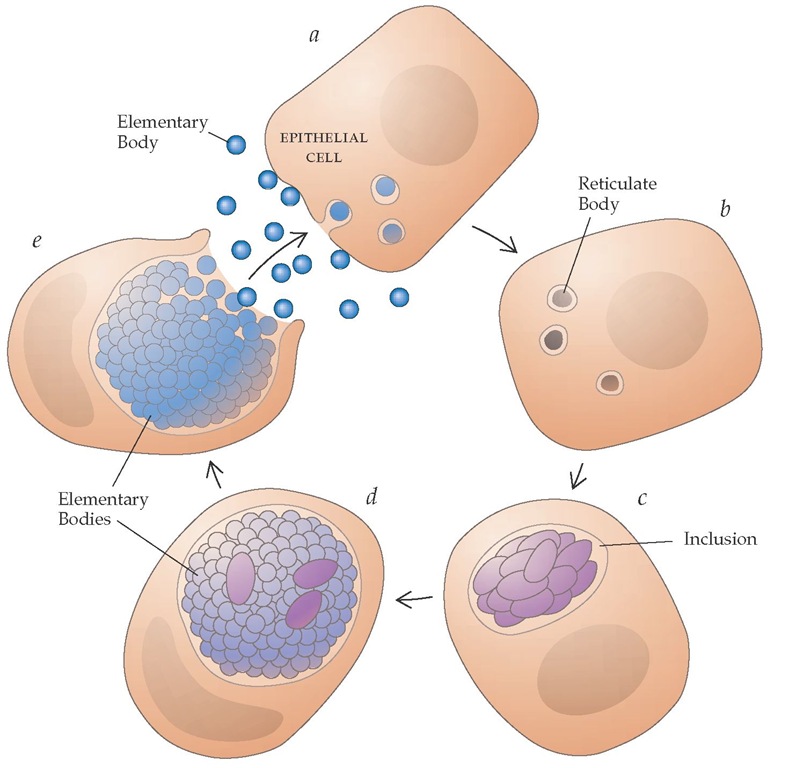

All chlamydiae share a unique life cycle characteristic of the genus [see Figure 1].7 The organism is transmitted in an extracellular nonreplicating form known as the elementary body. The elementary body adheres to and is phagocytosed into a host epithelial cell. Once inside the epithelial cell, the elementary body transforms into the intracellular replicative form of the organism, the reticulate body. Reticulate bodies divide by binary fission within membrane-bound vacuoles called inclusions. After approximately 36 hours, reticulate bodies condense into elementary bodies, the inclusion ruptures, and the elementary bodies disperse to infect adjacent epithelial cells or to be transmitted to other hosts. A unique feature of the chlamydial inclusion is its ability to resist lysosomal fusion; the mechanism of resistance is as yet unknown. The intracellular milieu also provides the organism with nutrients and serves as a refuge from host immune defense mechanisms.

Although chlamydiae were initially thought to be large viruses, they in fact possess both DNA and RNA, have a cell wall and ribosomes similar to those of gram-negative bacteria, and are inhibited by a variety of antimicrobials (see below).7 C. trachomatis, C. psittaci, and C. pneumoniae all share a genus-specific lipopoly-saccharide antigen. The commonly available complement fixation test for Chlamydia measures antibodies against this antigen. The three species can be differentiated serologically with the mi-croimmunofluorescence test, which is directed against epitopes in the major outer membrane protein (MOMP).

Characteristically, chlamydial species produce chronic, persistent, and often asymptomatic infections of the epithelial lining of the eye, respiratory tract, and urogenital tract. Infection of epithelial cells induces secretion of cytokines and initiation of an innate immune response. Induction and persistence of a chronic inflammatory response may eventually result in fibrosis, scarring, and other chronic sequelae of infection.

In cell cultures, chlamydia species are susceptible to many antimicrobials, including tetracycline, doxycycline, erythromycin, azithromycin, rifampin, clindamycin, ofloxacin, and levofloxa-cin. Although antibiotic-resistant strains of Chlamydia have been described, clinical antimicrobial resistance has yet to become a frequent problem in treating chlamydial infections.

Diseases Due to C. trachomatis

Unlike C. pneumoniae, which appears to have only a single serotype, and C. psittaci, whose number of serotypes is unknown, C. trachomatis has at least 18 distinct serotypes (serovars).10 These serotypes confer tissue tropism and disease specificity: serovars A, B, Ba, and C are associated with trachoma, whereas serovars D through K are associated with sexually transmitted and peri-natally acquired infections. Serovars L1, L2, and L3 are more invasive than the other serovars, spread to lymphatic tissue, and grow readily in macrophages; they produce the clinical syndromes of lymphogranuloma venereum and hemorrhagic proc-tocolitis.

Laboratory diagnosis

Laboratory testing for C. trachomatis has evolved considerably over the past decade. Four types of confirmatory procedures are now available: (1) direct microscopic examination of swabs or tissue scrapings utilizing fluorescent antibody staining (DFA); (2) cell culture isolation of the organism; (3) detection of chlamyd-ial antigens or genes in specimens by immunologic means or nucleic acid amplification testing; and (4) serologic testing for antibodies to C. trachomatis [see Table 2].

Except in cases of inclusion conjunctivitis, DFA has largely been abandoned for diagnosis of chlamydial infection. Even in inclusion conjunctivitis, nucleic acid amplification testing of con-junctival smears is probably a better choice because of its higher sensitivity. Cell culture techniques for isolation of Chlamydia are not widely available and have numerous drawbacks: culture has exacting requirements for specimen transport and is technically demanding and expensive; moreover, its sensitivity is only 60% to 80% of that of newer diagnostic tests.12 For those reasons, non-culture alternatives utilizing antigen or gene detection are the diagnostic methods of choice in most cases. The least expensive and most widely used of the nonculture tests are enzyme-linked immunoassays that detect chlamydial antigens on urethral or endocervical swabs. These tests, however, have limited sensitivity and specificity and cannot be used to test vaginal swabs or urine for Chlamydia.

The newer nucleic acid amplification tests, such as poly-merase chain reaction (PCR), ligase chain reaction (LCR), and transcription-mediated amplification (TMA), are the most sensitive and specific of the currently available tests.13 Uniquely, these tests have high accuracy even when used on specimens that contain only small numbers of organisms (e.g., first-void urine or vaginal swabs). The ability to use such specimens is of particular importance because their ease of collection facilitates patient compliance and community-based screening programs.

Table 1 Comparative Features of Chlamydia species

|

Species |

C. trachomatis |

C. psittaci |

C. pneumoniae |

|

Natural hosts |

Humans |

Birds, mammals |

Humans |

|

Mode of transmission |

Sexual; close personal contact; maternal/ infant |

Zoonotic |

Respiratory droplets |

|

Typical diseases |

STDs, LGV, trachoma |

Pneumonia, psittacosis |

Upper respiratory infections, pneumonia, atherosclerotic vascular disease |

|

Risk groups |

STDs: sexually active adolescents and young adults Trachoma: young children in arid, unhygienic, crowded conditions |

Bird fanciers, pet-shop workers, veterinarians, animal and poultry workers |

Young children, older adults |

|

Number of serotypes |

18 |

Unknown |

1 |

LGV—lymphogranuloma venereum

STDs—sexually transmitted diseases

Serologic tests are of little value in the diagnosis of most chlamydial ocular or genital infections.14 They are useful only in invasive syndromes such as pelvic inflammatory disease, epi-didymitis, lymphogranuloma venereum, and infant pneumonia, which are associated with significant increases in both microim-munofluorescence and complement-fixing antibodies.

Sexually transmitted diseases

C. trachomatis is the most common bacterial cause of sexually transmitted disease (STD) in the United States, being responsible for an estimated four million cases a year.2 The spectrum of illness attributable to these infections parallels that of gonococcal infection. In men, the most common syndromes are nongonococ-cal urethritis and acute epididymitis. In women, mucopurulent cervicitis, urethritis, bartholinitis, acute salpingitis, and perihep-atitis are the syndromes most commonly seen. Inclusion conjunctivitis, proctitis, and Reiter syndrome affect both sexes.

Sexually transmitted C. trachomatis infection has a widespread distribution and a high incidence and prevalence in adolescents and young adults in the United States and Europe.15 The age of peak incidence is the late teens and early 20s. Prevalence has been reported at 3% to 8% in general medical clinics and urban high schools, over 10% in asymptomatic military personnel undergoing routine physical examination, and as high as 15% to 20% in men and women attending STD clinics.16,17 The highest prevalences of infection have been observed in persons who are single, have multiple sexual partners, are not using barrier contraception, report genital symptoms, have an infected sexual partner, or are attending a high-risk clinic such as an STD clinic. As many as 90% of infections in many settings may be asymptomatic and are thus discoverable only by screening. Recurrent chlamydial infections—often from untreated sexual partners— are common in high-risk groups.

C. trachomatis initially infects the columnar epithelium of the genital tract and induces an inflammatory response that may persist for months or years. Serious sequelae, such as scarring of the fallopian tubes and damage to the upper genital tract, occur most often with repeated or persistent infections.19 The mechanism through which repeated infection induces inflammation and subsequent complications is not clear. The C. trachomatis 60 kd heat shock protein has been implicated in these deleterious inflammatory responses and may induce antibodies that cross-react with human heat-shock protein. Other chlamydial proteins also may be important in this process.20 Host genetic susceptibility may also play a role: persons with particular HLA haplotypes appear to be more susceptible to scarring with either genital or ocular infection.21

Nongonococcal Urethritis

Diagnosis Nongonococcal urethritis (NGU), the most common chlamydial urogenital infection in men, typically presents with burning pain on urination, urethral discharge, or urethral itching. A discharge from the urethra may be apparent on observation or may be visible only after stripping the urethra. The discharge is generally clear or mucoid, but it may be mucopurulent or purulent.22 However, up to half of the men with C. trachomatis infection of the urethra will have no clinical manifestations of urethritis. Many of these patients will nevertheless have an increased number of leukocytes on Gram stain of a urethral smear. A presumptive diagnosis of NGU can be made on the basis of a leukocytic urethral exudate (> 4 polymorphonuclear leukocytes [PMNs] per 1,000x oil-immersion field) in the absence of concurrent gonococcal infection by Gram stain or culture [see Table 2]. About 40% of such cases of presumptive NGU are caused by Chlamydia; the remainder are caused by Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma genitalium, and other microbes.23 The specific diagnosis of chlamydial infection can be confirmed by a nucleic acid amplification assay such as PCR or LCR, an antigen detection test, or culture.

Treatment Men with presumed or confirmed NGU should be treated with oral doxycycline, 100 mg twice a day for 7 days, or azithromycin, 1 g orally as a single dose. The two regimens appear equally effective.24 The azithromycin regimen offers the advantage of single-dose therapy but is considerably more expensive. Female partners of men with NGU should be examined and treated for presumed concomitant chlamydial infection.

Epididymitis

In 1% to 2% of men with chlamydial urethritis, the infection ascends in the genital tract to cause acute epididymitis. C. tra-chomatis is the major cause of acute epididymitis in heterosexual men younger than 35 years; other causes include Neisseria gonor-rhoeae and, less commonly, urinary pathogens such as Escherichia coli or Pseudomonas aeruginosa.25 Urinary pathogens are a more common cause of epididymitis in homosexual men who practice rectal intercourse and in men older than 35 years who have had urologic instrumentation or surgery.

Figure 1 Life cycle of Chlamydia. (a) Chlamydiae are transmitted in an extracellular nonreplicating form known as the elementary body. The elementary body adheres to and is phagocytosed into a host epithelial cell. (b) Once inside the epithelial cell, the elementary body transforms into the intracellular replicative form of the organism, the reticulate body. (c) Reticulate bodies divide by binary fission within membrane-bound vacuoles called inclusions. (d) The reticulate bodies then reorganize into elementary bodies; multiplication stops. (e) After 35 to 40 hours, the inclusion ruptures, and elementary bodies are released to infect adjacent epithelial cells or to be transmitted to other hosts.

Diagnosis Epididymitis caused by C. trachomatis typically presents as unilateral scrotal pain, fever, and epididymal tenderness and swelling. Testicular torsion should be excluded by a ra-dionuclide scan or Doppler flow study if the diagnosis is in doubt.

Treatment In some patients, epididymitis may be mild enough to be treated on an outpatient basis with oral antibiotics. In other cases, hospitalization is required for management of pain and initiation of parenteral antibiotics. Initial empirical therapy with ofloxacin, 300 mg orally or intravenously twice daily, is recommended until the etiologic agent is identified [see Table 2].

Mucopurulent Cervicitis

Endocervical infection with C. trachomatis is considered the female counterpart of male urethritis.

Diagnosis C. trachomatis cervical infection is often clinically silent, although a careful speculum examination will reveal mu-copurulent cervicitis in some cases. When clinical manifestations are present, they are nonspecific—for example, vaginal discharge, vaginal bleeding, lower abdominal pain, or dysuria. On examination, findings include a yellow or green mucopurulent discharge from the endocervical os, the presence of cervical ec-tropion, edema in the area of ectropion, and easily induced mu-cosal bleeding.27 A Gram stain of the endocervical exudate typically shows large numbers of PMNs. Women with suspected mucopurulent cervicitis should be evaluated for both chlamydi-al and gonococcal infection [see Table 2].

Treatment Chlamydial mucopurulent cervicitis is best treated with a single dose of 1 g of azithromycin. This regimen is effective and safe. Although more expensive than doxycycline, azithromycin is cost-effective because adolescents often fail to complete a 7-day course of doxycycline.28 Unlike doxycycline, azithromycin appears to be safe during pregnancy and is used by many practitioners for treatment of chlamydial mucopuru-lent cervicitis or cervical infection in pregnant women.29 Sexual partners of women found to have chlamydial cervical infection or mucopurulent cervicitis should be examined and empirically treated for chlamydial infection.

Table 2 Clinical Characteristics of Common C. trachomatis Infections in Adults

|

Men |

Infection |

Symptoms and Signs |

Presumptive Diagnosis |

Definitive Diagnosis |

Treatment |

|

Nongonococcal urethritis |

Urethral discharge, dysuria |

Urethral leukocytosis; no gonococci seen |

Urine or urethral NAAT |

Azithromycin, 1 g p.o. (single dose) or Doxycyline, 100 mg p.o. b.i.d., for 7 days |

|

|

Epididymitis |

Unilateral epididymal tenderness, swelling; pain; fever; presence of NGU |

Urethral leukocytosis; pyuria on urinalysis |

Urine or urethral NAAT; urine culture |

Outpatient: Ofloxacin, 300 mg b.i.d. for 10 days or Ceftriaxone, 1 g I.M., plus doxycycline, 100 mg p.o., b.i.d., for 7 days |

|

|

Proctitis |

Rectal pain, discharge, bleeding; history of receptive anal intercourse |

> 1PMNs/OIF on rectal Gram stain; no gonococci seen |

Rectal culture or DFA (NAAT untested) |

Doxycycline, 100 mg p.o., b.i.d., for 7 days |

|

|

Conjunctivitis |

Ocular pain, redness, discharge; simultaneous genital infection |

Gram stain of conjunctival swab negative for bacterial pathogens; PMNs on smear |

DFA or NAAT on conjunctival swab |

Azithromycin, 1 g p.o. (single dose) or Doxycyline, 100 mg p.o., b.i.d., for 7 days |

|

|

Women |

Cervicitis |

Mucopurulent cervical discharge; cervical bleeding; cervical edema |

> 20 PMNs/OIF on cervical Gram stain |

Urine or cervical NAAT |

Azithromycin 1 g p.o. (single dose) or Doxycycline, 100 mg p.o., b.i.d., for 7 days |

|

Urethritis |

Dysuria, frequency; no hematuria |

Pyuria on UA; negative urine Gram stain and culture |

Urine, cervical, or urethral NAAT |

Azithromycin, 1 g, p.o. (single dose) or Doxycycline, 100 mg p.o., b.i.d., for 7 days |

|

|

Salpingitis |

Lower abdominal pain, adnexal pain, cervical motion tenderness |

Evidence of mucopurulent cervicitis |

Urine or cervical NAAT |

Outpatient: Ofloxacin, 400 mg b.i.d., p.o., plus metronidazole, 500 mg p.o., b.i.d., for 14 days or Ceftriaxone, 250 g I.M. plus doxycycline, 100 mg p.o., b.i.d., for 14 days |

|

|

Conjunctivitis |

Ocular pain, redness, discharge; simultaneous genital infection |

Gram stain of conjunctival swab negative for bacterial pathogens; PMNs on smear |

DFA or NAAT on conjunctival swab |

Azithromycin, 1 g p.o. (single dose) or Doxycycline, 100 mg p.o., b.i.d., for 7 days |

DFA—direct fluorescent antibody

NAAT—nucleic acid amplification test

NGU—nongonococcal urethritis

OIF—oil-immersion field ]

PMN—polymorphonuclear neutrophil

UA—urinalysis

Acute Urethral Syndrome in Women

In women presenting with dysuria, frequency, and pyuria, C. trachomatis is the pathogen that is most commonly identified if urine cultures fail to find E. coli, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, or other uropathogens.30 Chlamydial infection should be considered to be the cause of so-called dysuria-pyuria syndrome when the urine culture does not demonstrate expected urinary bacterial pathogens, symptoms have been present for more than 7 days, the patient has a new sexual partner, or concomitant mucopurulent cervicitis is present on examination.30,31

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

C. trachomatis is thought to account for about half of all cases of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in the United States.32 Ascending intraluminal spread of C. trachomatis from the lower genital tract can produce endometritis, endosalpingitis, and pelvic peritonitis. On examination, evidence of mucopurulent cervicitis is generally found in women who have laparoscopical-ly verified salpingitis due to C. trachomatis.

Diagnosis Chlamydial salpingitis often produces fewer clinical symptoms and signs than gonococcal or anaerobic sal-pingitis.33 However, patients often present with lower abdominal pain, adnexal tenderness, vaginal discharge or bleeding, and uterine tenderness. They may or may not have fever.

Treatment Empirical treatment of PID must provide antimicrobial coverage for the major pathogens, including C. trachoma-tis, N. gonorrhoeae, and vaginal anaerobes [see Table 2]. Screening of high-risk young women for chlamydial cervical infection followed by treatment has been shown to prevent subsequent PID in a prospective cohort study.34 Thus, chlamydial screening of all sexually active adolescent girls and women younger than 25 years with new sexual partners is strongly recommended.

Complications Infertility and ectopic pregnancy are important sequelae of chlamydial tubal infection. Antecedent C. tra-chomatis PID has been linked to infertility from fallopian tube scarring. In more recent studies, demonstration of persistent, slowly replicating C. trachomatis in tubal tissue suggests that these patients may have chronic infection.

Perihepatitis, or Fitzhugh-Curtis syndrome, develops in a subset of women with chlamydial salpingitis. These patients present with right upper quadrant pain, fever, and often adnexal tenderness. The diagnosis can be established with an endocervi-cal nucleic acid amplification test for chlamydia or by demonstration of high titers of antibody to C. trachomatis.