Graphics Reference

In-Depth Information

Figure

.

.

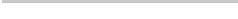

Conditional association plot for the UCB admissions data. For each individual association

plot, rows correspond to gender and columns to admission

and admission, given department), stratified by department. Clearly, the situation in

department A (more women/less men admitted than expected under the null hy-

pothesis) results in the rejection of the hypothesis of conditional independence. In

Fig.

.

, data-driven cut-offs (derived from the maximum test for conditional in-

dependence) are used, resulting in more colorful shading than the fixed cut-offs in

Figs.

.

and

.

.

AFour-WayExample

12.4.3

As a four-wayexample, we usethe punishment data (Andersen,

)froma study of

theGallup Institute inDenmarkin

regarding theattitude ofarandomsample of

peopletowardscorporalpunishmentofchildren(seeTable

.

).hedata consist

offourvariables. Attitude isabinaryvariable indicating whetherapersonapprovesof

moderatepunishmentofchildren(“moderate”),ordisapprovesofanypunishmentof

children (“no”). Memory indicates whether the person recalls having been punished

as a child. Education indicates the highest level of education (elementary, secondary,

high). Finally, age indicates the age group in years (

-

,

-

,

).

In a first step, we create a mosaicplot for an exploratory view of the data: atti-

tude towards punishment is clearly the response variable here and should be used

for the last split via highlighting. Furthermore, we expect age and education to have

an influence on both memory and attitude, so they should be used first for splitting

as stratifying variables. In fact, the question is whether memory has some influence

on attitude, given age and education. We choose to create a three-way mosaicplot of

the hypothesized explanatory variables (first splitting horizontally by age, then ver-

tically by education, and finally horizontally again by memory), and to have attitude,

+