Civil Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

lapping the ends. Take time to bend the bars where

you need it, to keep them near the vertical center of

the footing. Then put the steps in, if any, and pour the

other half on top.

For ready-mix, you should have the reinforcing rod

and bulkheads in place. I use short lengths of bar

driven into the bottom of the trench, along with the

grade stakes, and fasten the long bars to them with tie

wires to keep them up off the ground. Let concrete

cure at least two days. In freezing weather, insulate

over the pour with straw or sawdust to keep in the heat.

⁄/¢"

Other Foundations

There are a few other options for building founda-

tions. A low-cost foundation can be constructed from

concrete block on a footing. You can leave it as is, if you

don't mind looking at it, or you can parge the block

with mortar to hide it. A poured-concrete foundation

is strong but ugly, and requires form work. Both can

be stone- or brick-veneered, set on the footing. How-

ever, building codes do not allow for the building

weight on the veneer.

A more expensive, but innovative, foundation is the

precast dense concrete foundation that is custom

designed for each house. The entire basement for one

log house we built was installed in three hours.

Installed with a crane, the 10-foot panels come with

Styrofoam insulation and studs predrilled for electric

wiring. The panels can include basement steps, foun-

dation for a chimney, ledges for stone or brick veneer,

ledges for the floor-joist system, windows, and doors.

Covering exposed concrete foundations with stone

veneer requires the use of masonry mortar (which is

different from footing mixture). I use a mix of one part

masonry cement to three parts sand, and I use one

part lime to two parts Portland to make the masonry

cement — that's one part lime, two parts Portland, and

nine parts sand. There are lots of other formulas, but

this has worked nicely for me over several years. And

it's cheaper than buying masonry cement or premix.

Mortar should be thoroughly mixed in a box or

wheelbarrow with a hoe, using enough water for a

slightly stiff mix. Most masons use it as dry as possi-

ble to avoid smearing and running, but it bonds to the

stone better if it's wet ( just dry enough not to run).

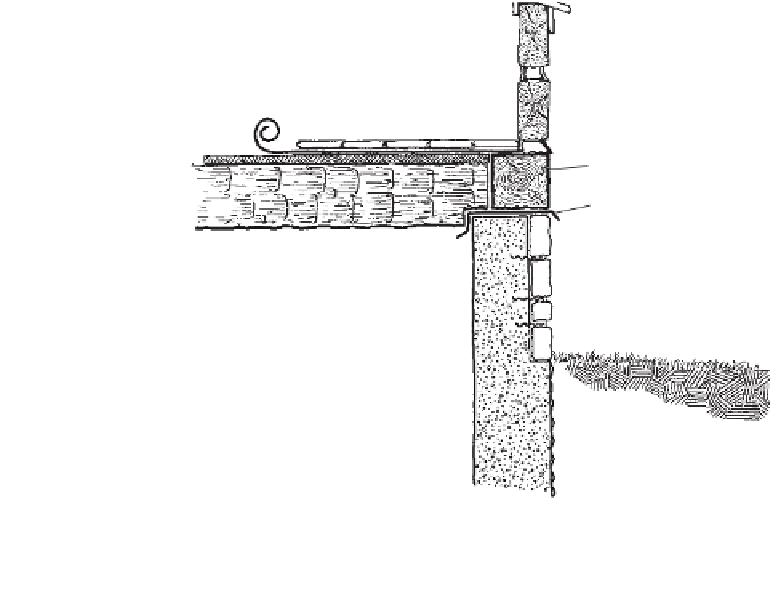

The floor joists can be set directly on the foundation ledge inside the

first logs, eliminating the need for attaching to the sill. Both the sill

and the joist end must be set on either metal flashing or pressure-

treated wood to act as a termite shield.

I don't mix masonry mortar in a cement mixer

unless I have plenty of help and plan to use many

batches. You'll find that if you work alone or with one

helper, it takes quite a while to use up a couple of cubic

feet of mortar, and you may mix but one or two

batches a day. Also, a lot of it gets caught in the tines

of the mixer and wasted when you wash it out.

Both concrete and mortar must be kept moist for

several days to complete the chemical reaction that

produces strength. Just letting it dry out doesn't work.

Wet burlap sacks are good to cover fresh work, or

sheet plastic. Spray with water, but not until the sec-

ond day or you'll wash it away.

And just don't do mortar or concrete work in freez-

ing weather. Portland cement generates a little heat

the first day as the chemical action goes on, but it's

only good to about 30°F. It's best to use insulation and

sheet plastic to hold heat and ground temperature

next to the work the first two cold nights.

Below 28°F or so, just don't lay stone or build ma-

sonry aboveground. The chill will permeate even insu-

lation in time, which will freeze your work. Footings

down in the ground, with some straw over them for

insulation, can be poured safely down to about 20°F.

I don't use antifreeze solutions in mortar or concrete.