Civil Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

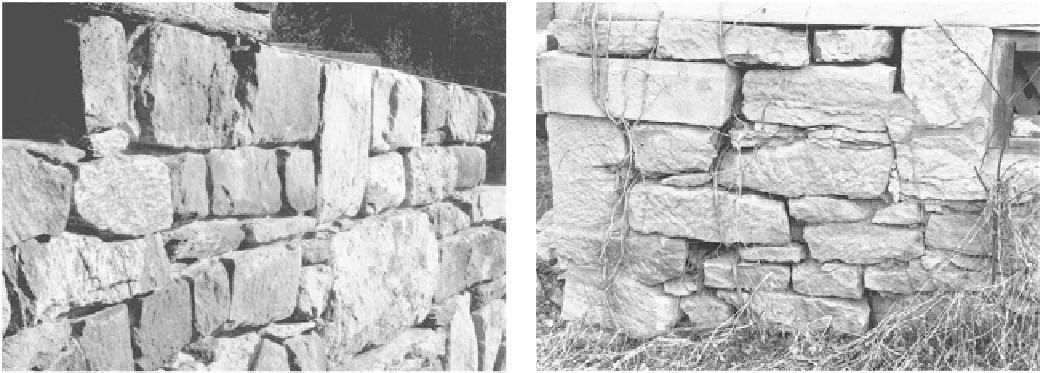

Large stones require no more time to lay than small ones. This mortared

stone foundation was for a log blacksmith shop restored as a cabin on

Greene Mountain in Virginia. The space for a foundation vent and the

metal flashing between masonry and sill are building code requirements.

Drystone foundations allow air to circulate under the house, which

keeps down moisture but makes the floors colder. Drystone requires

no footing or mortar but must be carefully laid to withstand flexing

from freezing and thawing earth.

bonding. Then trim any excess mortar. Rake the joint

at least half an inch deep so the faces of the stones

project. Try not to smear the mortar. You can clean up

the next morning with a wire brush.

A drystone foundation is more nearly authentic

pioneer, but is also a haven for snakes, and is often not

allowed by building codes. One advantage is that it's

less work, because no mortar is used and no footing is

necessary. Water can get under the stones and freeze

anyway, so there's no point to a footing below frost

line. Most of the water drains out from between the

stones naturally. This type of masonry requires good,

flat-surfaced stones, however. And that means a lot of

searching for the right rock, wedging between, or a lot

of stone cutting and dressing. A foundation obviously

shouldn't totter, or folks in your house will tend to

become uneasy. So wedge stonework with bits of rock

or metal. These shims should always be flat, or flexing

with temperature changes will drive them out.

In the process of the ground's freezing, swelling,

settling, and washing, you'll notice some changes in

your drystone foundation; but if your stones are good

and wide, and the piers cover a lot of ground area, you

can live with it nicely. Drystone lets air under your

house, making it colder in winter but keeping it drier.

I don't advise, however, letting your toddler stick his

fingers into those inviting, dark recesses after large,

curiously patterned “wiggle worms.”

Stone Foundation

Now, about the stones in the foundation. First of all,

haul in more than you could possibly need. You'll still

run short. If you can, get stone that's flat top and bot-

tom. The face is a matter for your own taste, but struc-

ture is important here, so lay as much as possible hor-

izontally. I've benefited from living in the Arkansas

and Missouri mountains with the best building stone

everywhere for the picking, and I've lived in Missis-

sippi and in central Virginia where rock gathering is a

long-distance adventure. Use a little mortar on the

footing concrete, maybe one inch thick, wetting it first,

just as you will for each course or layer of stone on pre-

vious drywork as you go up.

Lay the stone any way you choose, but cover the

joints between stones with the next layer, brick fash-

ion. You invite a cracked foundation if mortar joints

align vertically. I like to lay stone flat, or ledge, with

the edges showing. I vary this with a square, rounded,

or angled stone occasionally. A wall laid with the

stones standing on edge is weaker, unless very thick.

Make sure each stone will stay where you want it

before you mortar it. That way it will be there from

now on, even if the mortar erodes away, as did the

mud, clay, and lime mortar of earlier foundations and

chimneys. Lay about one inch of mortar, back from the

face an inch, then set the stone, rocking to ensure