Civil Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

time operation. When each section was poured and set

up, we went on to the next, leaving rebar extending to

tie the sections together.

A contractor I know once dug out too much for this

operation and the basement wall fell in, leaving a hole

you could drive a truck through. Brick damping had

so weakened the basement walls that, as a result of this

mishap, the owner decided to demolish the entire

1840s house. It wasn't a log house, but a huge, beau-

tiful Italianate-style brick plantation house, which

cracked and settled in a way logs would not have.

Preparing for the Log Setup

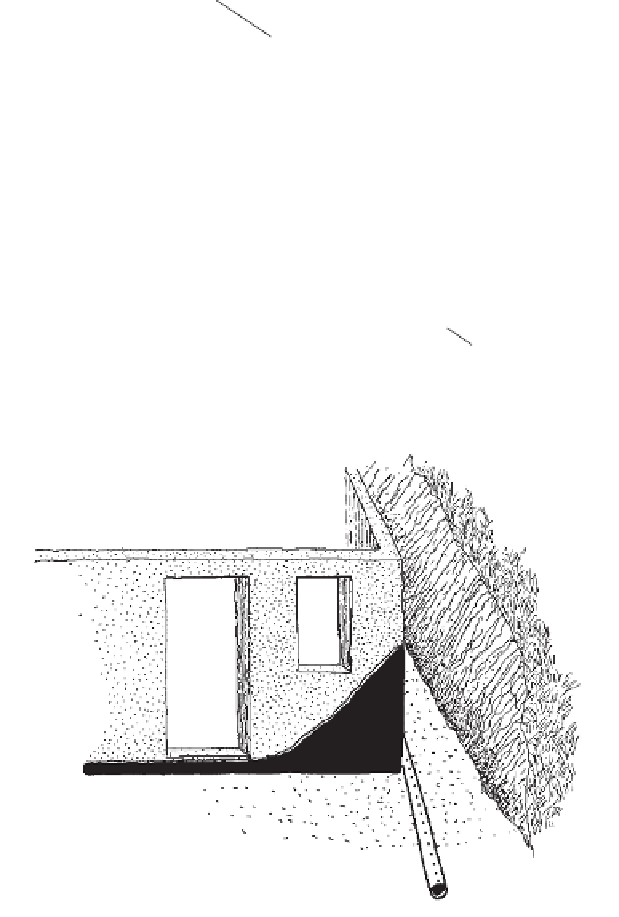

With either a basement or a continuous foundation,

you can actually do away with sill logs, which gener-

ally support the floor joists. Historically, the joists

were notched into the sills. Today, many builders use

galvanized metal joist hangers. You may leave a wide

foundation, with the first log at the outside and the

ends of the joists on the inside, resting on the masonry

itself. The first log is below floor level, as is the sill, but

it doesn't have to support the floor.

Bring your foundation up a foot or more off the

ground before you lay the first log. Eighteen inches is

better, because termites don't like to travel far from

ground moisture. And you want that much crawl

space. After the logs are in place, fill in any gaps to give

more support, using mortar and stone where needed.

And use metal flashing between the foundation and

the first logs.

I am often required to set heavy bolts into the foun-

dation masonry to anchor the sill logs. This is com-

monly done in conventional stud-wall construction

and in post-and-beam construction. It would be of no

value in a log house, however, unless some way were

devised to fasten all the logs together, from the foun-

dation on up. The weight of the logs themselves holds

the house together, and I have never seen a dovetail-

notch cabin blown apart by wind. (The roof might

depart in a really heavy gale, but we talk about how to

prevent that in the chapter on roofs.) But building

codes often require anchor bolts. And they do help

keep the sill logs in place laterally.

Set first logs and joist ends on metal flashing or on

pressure-treated wood (building codes allow either) to

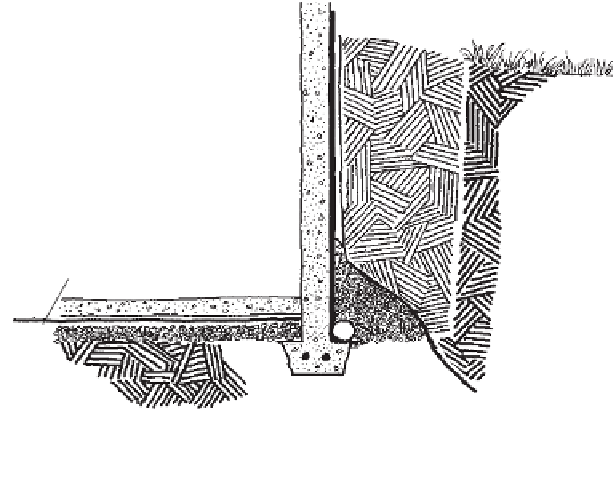

Perforated drainpipe must be laid around a basement wall below floor

level to carry away groundwater. Gravel and filter fabric are necessary

to keep backfill soil from clogging the pipe.

Basements must be sealed against moisture all the way up the walls,

which will be backfilled. Drainpipe, in conjunction with the sealant,

will keep water from soaking or seeping into the basement walls.

foil termites and stop moisture damage. Moisture

wicks up from the ground, through the foundation,

and the flashing stops it. The treated wood doesn't

stop moisture penetration, but the poison of the treat-

ment kills both the rot fungus and hungry termites.

Aluminum or galvanized flashing will work, but we

use copper. It ages into invisibility and, being thicker,

lasts longer. But it costs more too. (Depending on the

market rate per pound, it costs from $200 to $300 for

a 2-by-50-foot, 100-pound roll.)