Civil Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

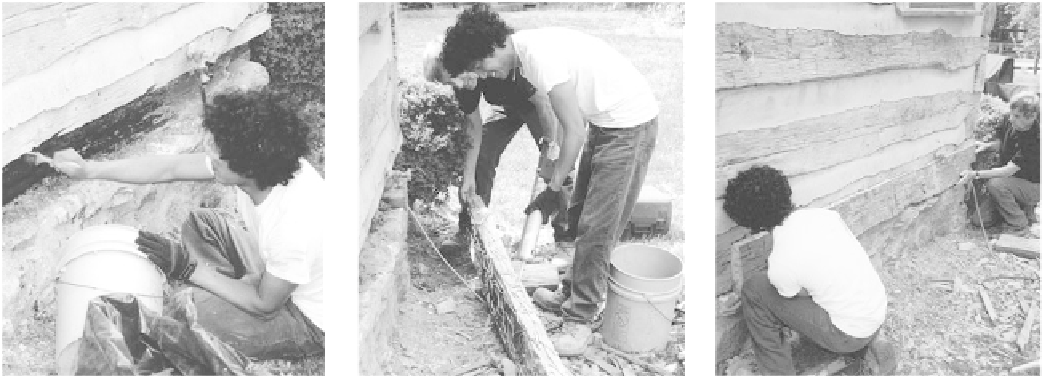

Decayed wood has been removed here, and

the borate-based preservative is being applied

to stop dry rot and possible insect damage.

We use four coats, brushed on or sprayed on.

Construction adhesive is applied to the re-

placement log section which, in this case,

was most of the face of this log.

The replacement section is put in place.

Finish nails, along with the glue, will hold it.

Clear caulk is used to seal out water.

12 inches, using a vertical lap instead of horizontal so

the patch shows less. It's a good idea to leave the

replacement piece a little long, say half an inch, to

allow for adjusting the butt ends of the lap joint. If

they don't fit tight, kerf the gaps with a handsaw to let

them come together tighter. Then, when the joint is

tight, glue, peg, or nail, and cut off what's left at the

end, if anything.

The lap joint can be done without jacking up the

house, so of course it's preferable if the notch area is

sound. All too often, though, the notch is where the

damage is, and it must be replaced. If only the notches

are bad, you can do the same half-lap repair, replac-

ing the notched section and using the split-off tech-

nique mentioned before.

If the house has settled, which it probably has in

this case, do raise it in small increments over several

days, back to just above level. Drive replacements

(logs, stones, wedges — whatever) in tight, then let the

house wall back down. The logs will compress until

rechinking distributes the weight from above along

their entire lengths.

For higher replacements, we use jack posts, which

adjust to most workable heights. One goes inside,

again, and one outside, with channel iron between.

Avoid automotive-type jacks under vertical posts,

because this arrangement can buckle and let the

whole house come down — sometimes onto you.

Rechinking

This is a case for a very close look at the condition of

the log house before you start, or better, before you part

with any money. Rechinking is just about always nec-

essary. If anything turns off the enthusiasm to restore

a log house, the dilemma of replacing rotten, unwork-

able chinking is it. At best, the expansion of the logs

with moisture has pushed the old chinking out, to leave

a direct channel for rainwater behind the masonry.

Often, the logs have rotted from this, or the old

chinking is so broken up it has to come out anyway.

I have found the chinking space between the logs

filled with solid clay and solid concrete as well as

wedged with large rocks, small stones, full bricks and

broken bricks, moss, grass, mud mixed with horsehair

or straw, and wood splits (or “chinks,” the derivation

for the word

chinking

) smeared with a layer of mud

or concrete in varying thicknesses. (More recently,

chunks of Styrofoam have been wedged in.) Early

builders did not have access to metal lath and the

materials we have and so they stuffed anything and

everything they could into the cracks. By doing this,

they actually sabotaged the health of the logs, and

therefore the house, by holding moisture against the

wood.

The best thing to do with old chinking is to knock

it all out. Then, if the log wood is soft or bug-eaten,