Civil Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

the other side. The door was hung, and usually

secured with the simple lift latch, with its latch string

hanging outside.

Board floors downstairs and up were often riven,

though sometimes a primitive sawmill or whipsaw,

powered by two men or a water wheel, produced sawn

stock. These saws were used as early as the settlement

of Jamestown, and they were quite often added to

water-powered gristmills in the new settlements. A

board floor was a source of pride for the pioneer wife.

It was pegged or nailed, with cracks lessened during

installation by prying with a bar set in bored holes in

the joists. Smoothing the rough lumber was some-

times accomplished by rubbing with sand and stones.

The pioneer fireplace was of stone with clay or mud

mortar. The chimney was often of sticks laid like the

logs of the house, lined with “cats” of mud or clay.

These chimneys were firetraps, and unless used and

maintained constantly, they fell apart in the rains. But

they were easy to build, went up fast, and could be

built with no special skills. As the mountain settle-

ments became less remote, itinerant masons began

building stone chimneys of really fine craftsmanship.

Many older cabins had new chimneys of stone added

after years of life with catted or loose stonework.

Chinking the early cabin was a continuing process.

Short, split boards were often laid at an angle in the

cracks and a mud-and-grass mixture plastered into

them. Sometimes thin poles were wedged in and cov-

ered with the mud or clay. Timber being plentiful, the

earlier cabins tended to be built with wide logs, leav-

ing little space for chinking, and only later were the

wide cracks of three to six inches much in evidence.

Chinking, along with the hard work of hewn-log

building, has probably been the major reason for the

near disappearance of log houses. The logs shrink

away from the filling as they season, or anytime dry

weather or heat contracts them. The resulting drafts

are likely to be the most memorable aspect of cabin

living to be recalled by an old-timer. Shakes, slats,

boards, and, later, tar paper were nailed over the

chinked cracks. Mud, clay, and lime mortar were

patched and replaced season after season. According

to Roberts, hewn-log houses in southern Indiana

had clapboards nailed over them as soon as they were

finished.

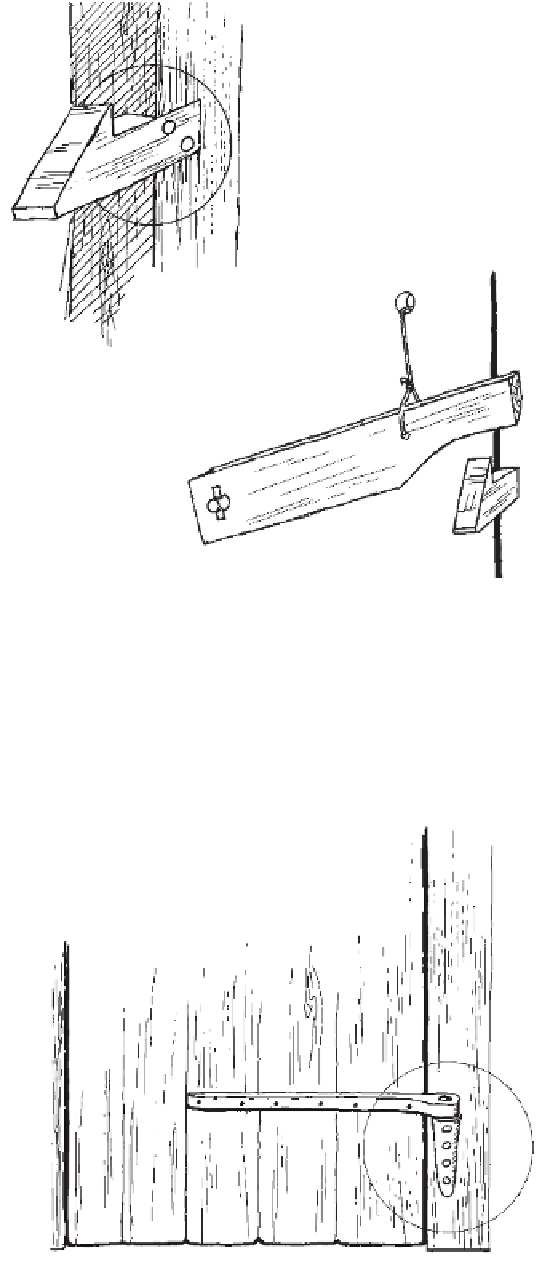

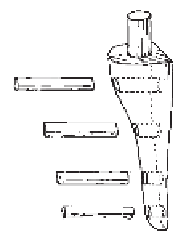

Wooden hinges and latches were often used where no blacksmith

was near. Made of tough wood such as hickory, the hinges were

greased with lard or bear fat. The door hook was mortised into the

doorjamb to allow the door to clear.