Civil Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

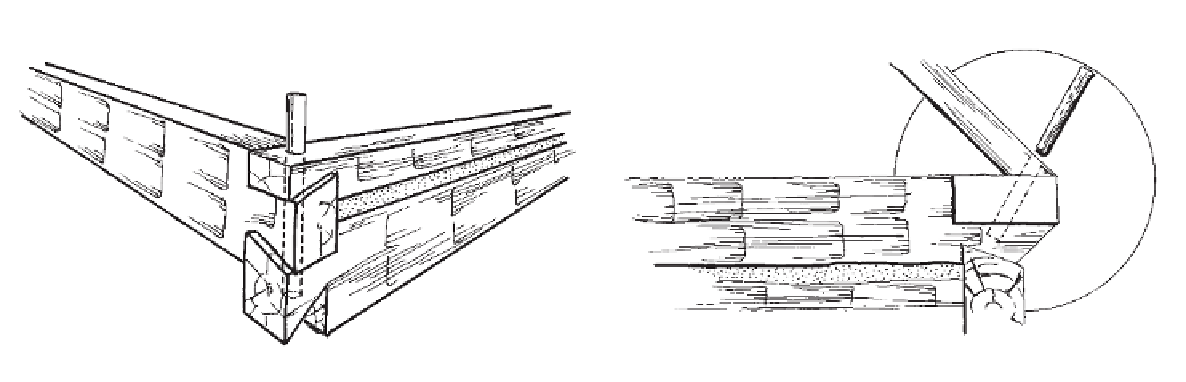

Top plate logs were pinned to hold against outward rafter thrust.

Sometimes an additional gable-end log was used above the plate,

as shown here.

The wide top plate, supported by a longer end log, provided a minimal

eave for the classic early hewn-log house. Slatting and shakes

extended slightly beyond the plate.

Occasionally, these large split shakes were pegged

in place with small wooden pegs, but this was rare.

Pegging was most effective as friction fastening, on the

principle of a headless nail, and was not suited for the

flexing of shakes in wind. The pegs would work loose,

so this is where nails were used early on.

Where a log gable was not used, a gable framework

of poles was pegged in, and shakes or riven clapboards

were used as covering. This allowed the house to be

put under roof sooner than the log gable, and the

whole was lighter. As sawn lumber became available,

the log gable was even less common, boards being eas-

ier than shakes or split clapboards to work and to

apply.

Door and window openings, if any, were sawed with

the crosscut saw. Into the cut log ends, facings of riven

boards were pegged or nailed to hold the logs in line.

Then shutters and doors were hung with leather,

wood, or iron hinges. Shutters were of split boards, or

sometimes tightly stretched animal skins. Rarely, the

first settlers had glass for windows. When they did, it

was usually fastened in place instead of being hung to

swing open, to avoid breaking it. The wooden shutters

let in light only with the outside air, and were often

kept shut all winter. In hot weather they let in gnats,

flies, and mosquitoes.

Doors were low affairs, made of split boards nailed

or pegged together, seldom angle-braced. To keep

them from sagging, the settler often used many of his

precious nails in a heavy pattern, clinching them on

These pieces were sometimes bound with rawhide or

pegged, as were the rafters. Pegs were often square, to

be driven tightly into the round auger holes.

The rafters themselves were usually poles, some-

times worked flat on top with the drawknife or adze.

They were fitted together in pairs at the peak with no

ridgepole. Most often a 45-degree roof pitch was used,

making figuring angles much simpler. Some steeper

roofs were built, and many less steep. Often the pitch

was a matter of guess, or of the builder's eye — as were

the very dimensions of the house itself.

Shakes for the roof were split with the froe, an

L-shaped tool driven with a heavy mallet. Early shakes

were quite long, often three feet or more, of the prime

timber the pioneers found. If laid without nails, the

shakes could be riven and used green. Nailed shakes

had to be seasoned to prevent splitting at the nails as

they shrank. Some early craftsmen split shakes of

green wood, others of seasoned. White oak, cypress,

chestnut, and cedar were most used.

If the settler had the knowledge and materials, he

could forge his own roof nails from bits of worn metal.

Even half a horseshoe, worn completely through at the

front, could be drawn out easily to produce a handful

of nails. Early blacksmiths used charcoal, where coal

was not available, in a simple sand-filled forge charged

with a wood-and-leather bellows. A nail-heading bar,

hammer, and anvil with cutoff hardy were the only

other tools necessary for this and most other simple

iron working.