Civil Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

were laid dry, with stone chips wedged between to sta-

bilize them.

Sill logs were laid, usually as the first front and back

logs. Unless a log house was square, it was almost

always longer down the ridgeline, so the floor joists, if

any, were laid front to back (the shorter dimension) on

the sills. These sills could be and were sometimes laid

as end logs, but not generally. If a raised floor was to

be built, joists were notched into the sills at regular

two- to four-foot intervals. Sometimes small split logs,

or puncheons, were notched and laid side by side upon

the sills with the flat sides up to form the floor itself.

These were worked with the adze when in place, and

fitted to each other at the edges. As they seasoned and

shrank, they could be slid together and another added

to take up the space.

If dirt or puncheons in the ground were to be the

floor, the log walls went up all the way to the ceiling

joists without interruption. The logs were notched —

either full dovetail, V-notch, square notch, or, most

often in later years, half-dovetail. In rare early cases

in the Midwest and East, a beautiful form of the full

dovetail was used in which each log was worked with

notches of the same compound angle. Rarely, too, the

diamond notch, half notch, and other experiments

were used.

In rare cases, corner-posting was used. The log

ends were shaped to vertical tenons and inserted into

mortises in heavy vertical corner beams, and pegged.

This is seen more often in Canada and is associated

with French building, but was done occasionally all

over. The Golden Plough Tavern in York, Pennsylva-

nia, built in 1741, is corner-posted. I also saw corner-

posting in a highly crafted ruin near Goochland,

Virginia — beyond repair, unfortunately. This cabin

also had diamond-head king posts, the one and only

example I've encountered in a log house. (I see around

100 a year.)

Logs were raised into position most often by hand.

Many log houses were 20 feet long or less, or were two

or more log pens of no more than that size. A man at

each end of such a log, perhaps with the aid of skids,

could just manage the job of raising it if no neighbors

were near for a cabin-raising. Let's picture the pioneer

father at one end, with perhaps his sturdy wife and a

half-grown boy at the other. Or the team of oxen or

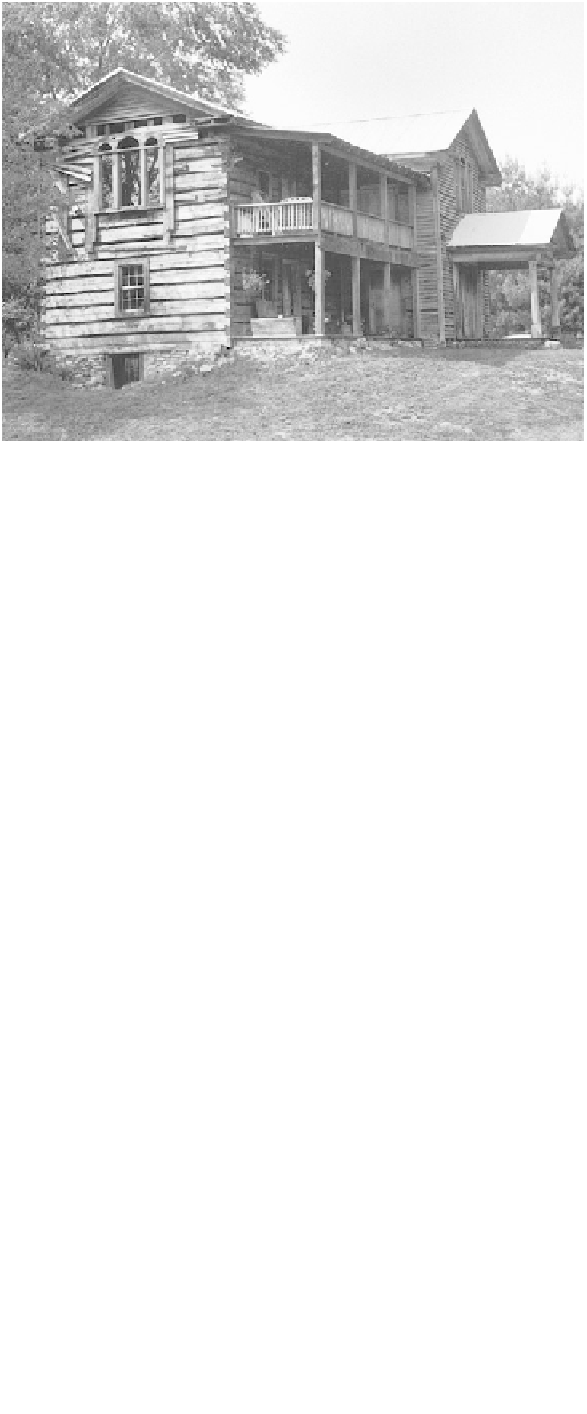

This log house has had some fanciful window treatment added, but

is otherwise typical of cabins added onto as a family's needs grew.

horses could be used to cross-haul the logs up skids

into place, with the final fitting done by hand.

Larger log houses, with logs up to 40 feet in length,

were built where there was help to raise them. These

always had midway partitions to brace the logs.

At ceiling height, usually seven to eight feet, joists

were notched in, again from front to back. Upon these,

as upon the floor joists, would be laid the split or rare

sawn boards of the combination ceiling and upstairs

floor.

Above ceiling height and more courses of logs was

laid the heavy top plate, which was wider than the wall

under it. In the finest tradition of log building that has

survived, the rafters terminated at this wide plate to

form a minimal eave. Sometimes the plate projected

inward, and the rafters were notched into it or over its

outer corner (the bird's mouth) to extend to form eaves.

The heavy plate also functioned to help take the

outward thrust of the rafters and the roof weight. In a

one- or two-story house, where there were no log

courses above the ceiling joists, these joists held

against this thrust, but some log knee wall above the

ceiling was common.

If the house were of the log gable type, the top plate

needed not be heavier. In this case no rafters were

used, so there was no outward thrust.

With rafters, split slats or poles were fastened

lengthwise to them for the shakes to be laid upon.