Civil Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

Flagstone

There are basically two ways to install a flagstone floor.

The stones can be laid on a concrete slab or they can

be bedded in sand over a filled floor space.

Both our Virginia house and our Missouri house

had stone floors. In Missouri, we gathered it from the

nearby creek bed, with some of the limestone as long

as five feet and maybe two inches thick. It's a very nat-

ural and durable material, though it was not widely

used by the early builders. A durable mortar is neces-

sary between the stones; the scarcity of mortar early

on may have been why few pioneers used stone.

I lay a vapor barrier of heavy plastic sheeting over

four inches of gravel, which is over the raked and tamped

earth, then cover this with sand. Each stone is then

bedded flat into the sand and mortared between the

edges. As in all stonework, it's a jigsaw puzzle. There's

really no point to a concrete slab beneath a flagstone

floor if moisture is sealed away from the base.

Flagstone can be sealed with masonry sealer, then

scrubbed and waxed as often as desired. I will warn

you that those beautifully flat stones you selected

never seem as smooth when laid, but you get used to

it. We did find that rigid furniture with more than

three legs had to be relegated to other, non-flagstone

floors in the house or wedged level in a permanent

place. We used those flexible wood-and-canvas direc-

tor's chairs, from necessity.

The Virginia log house section has heat pipe, a 400-

foot coil under cut soapstone, laid in a similar fash-

ion. Fill dirt, then gravel, went inside the raised foun-

dation, then was covered with six-mil plastic sheeting.

The pipe was laid on this and covered with the bed-

ding sand, which held the polybutylene coil in place.

We grouted the soapstone with masonry mortar and

sealed it with two coats of masonry sealer. We wax it

once a year or so.

Until recently, soapstone was available from reac-

tivated quarries in central Virginia. As of this writing,

however, it has become an expensive option, sold

through stone yards by the square foot. When sealed and

waxed, the black stone shows veins not unlike marble.

Today we build and restore log houses using a vari-

ety of flooring materials. The favorite in Virginia is

recycled heart pine, left with the patina of age on it.

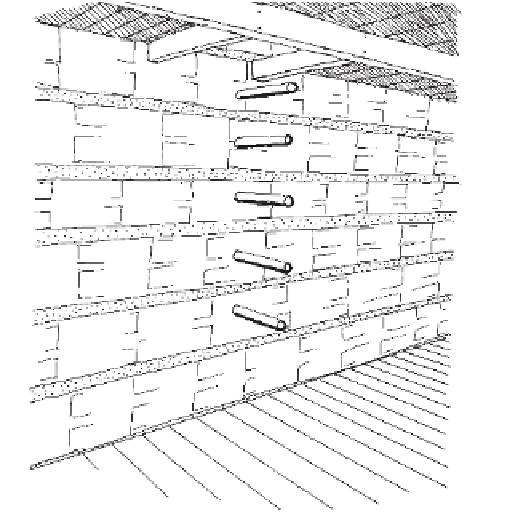

If there was no room for a stairwell, or if the loft was used just

for storage or a place for the children to sleep, then early builders

often installed a peg ladder into the log wall.

Often, we buy the remilled heart pine from old beams,

which is kiln-dried and tongue-in-groove. Other

choices are oak, maple, and even cherry flooring, all

over a subfloor. Upstairs we often space the joists

wider, using two-inch t.i.g. Sometimes we cover this with

sound-deadening material, then carpet. Often it's the

finished floor. Our non-soapstone floors are three-

inch t.i.g. heart pine, recycled from an old cotton mill.

Whatever you do, build your floor strong. Too long

a span between joists is no savings — nor is thin floor-

ing or subflooring. It's embarrassing for your guests

to fall through.

Stairs

You have a variety of stair choices to reach the upstairs

or loft. Most are used traditionally. The classic one is

a row of stout pegs out from the wall leading up to a

hole in the ceiling. You can nail a ladder to the wall,

but this won't meet building code either. Another

option is one of those disappearing or folding ladders.

Or you can build a steep staircase, at the end of the

house always, in a one-and-a-half story cabin. If it's at

the front or back of the house, you'll bump your head

on the roof before you reach the top. Again, check