Civil Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

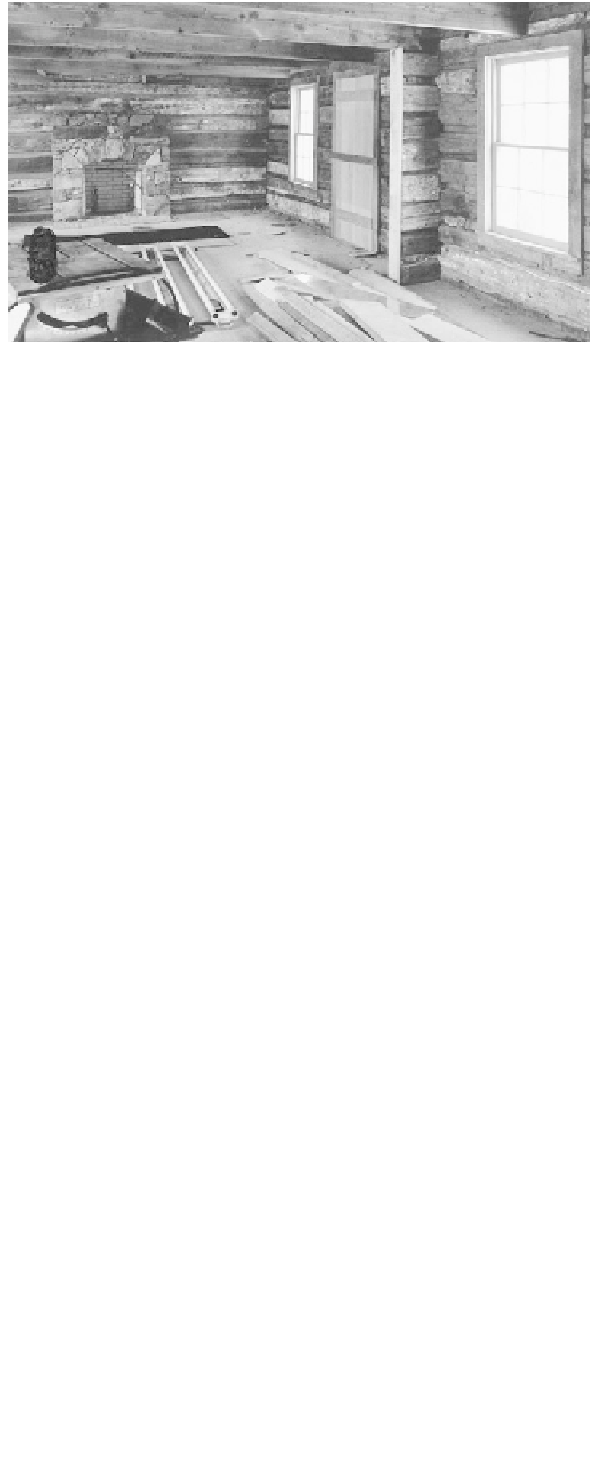

This is an example of an extended log wall where a three-way notch is

used to stabilize the end-to-end log with an intersecting log wall. Not

all the wall logs are end to end here, between windows. In this case,

the stub wall is a minimal two-foot wall because the owner wanted as

much open space as possible.

Preparing for Chinking and Electric

and Plumbing

Door and Window Bucks

Spike door, window, and fireplace bucks directly into

the ends of the logs, but not until the logs have sea-

soned and settled. Make a clean cut here. I leave the

log ends long until they're up, then make one long cut.

I like using the crosscut saw because I can control it

better, but a chain saw is faster. Only the greatest need

for haste drives me to use one.

One-inch oak or 2-inch pine is heavy enough for

these facings, and a 20-penny common nail is large

enough; use four nails per log. Don't use box nails in

oak. Those slender fasteners were designed for soft

pine, spruce, or fir. Even with common nails you may

have to drill an occasional hole, especially if your logs

are seasoned. I prefer the modern counterpart of the

old cut nail, square, now hardened for masonry, which

will go through anything. It's expensive, and you need

to drive its wedge shape with the grain, not across it, to

avoid splitting. Our forefathers bored and pegged these

facings with trunnels, the folk derivation of

treenail.

The facings (backs) hold the ends of the wall logs in

line, and should be mortised into and fastened to the

top spanner overhead and window or door sill log

beneath. After they're in place, you can pry off the

temporary strips (scabs) you nailed up as the logs went

into place. It seems it would be easier to start with the

facings themselves, but it's easier to trim the log ends

evenly when they're all up. And the logs need to settle;

allowing space for this has never worked for me. The

pioneers had an abundance of timber and built solid

log walls. Then they used the crosscut saw for the win-

dow and door cuts.

A time-saver before you raise the logs is one I learned

from Menno Kinsinger of Virginia's Shenandoah

Valley. Cut a chain-saw groove an inch deep about

1∏ inches in from the faces of the log on the under-

side. This is for the sloped chinking wire mesh to slip

into later, saving tricky fitting and nailing.

We also drill holes near door openings for electric

wire before we raise the logs. We use a one-inch bit to

drill up to wall switch height, then continue on up

through the top plate in at least one place. (See chap-

ter 11 for more on this process.)

Raising Logs

Getting the logs up onto the walls is a major under-

taking. Two to four men can wrestle 16- to 20-foot

hewn logs into place if the logs are under, say, 12

inches in diameter. But these are hard to lift to any

height. Long skids were usually the answer for the

early settlers, with the logs skidded up by hand or

cross-hauled by oxen or horses. Although it's slow, a

block and tackle will do the job. Skids or a vertical lift

from a tripod or boom provides the base for action.

The device I used for years was a full oak 2≈4

A-frame (gin poles) pivoted from the front bumper of

my Land Rover and braced with a guy cable over the

rig down to the trailer hitch. I ran the winch cable up

over a sheave at the peak and down to the log. Lack-

ing a winch, a ratchet hoist or “come-along” will do it

by hand. Either way, the log should be lifted at two