They Found Atlantis

A 1936 novel by Dennis Wheatley.

Third Reich

A view largely promoted by conventional scholars (Colin Renfrew, Donald Feder, et al) and authors with more interest in the occult than science, who insist that a belief in Atlantis as the lost homeland of an Aryan “super race” was aggressively championed by the leaders of Nazi Germany. This view has, in large measure, been sensationalized by television producers of several pseudo-documentaries depicting Atlantis as a fantasy with no basis in historical reality.

Hitler, Hess, Himmler, and Rosenberg are particularly singled out for their fanatic interest in “the lost continent,” and the post-World War I Thule Society— a mystical club—is sometimes cited as evidence of an early connection between interest in Atlantis and the Nazis.

But the Thule Society’s emphasis was far more Germanic than Atlantean. True, one of its members was Rudolf Hess, but the A-word cannot be found in any of his public speeches or private letters. The Myth of the 20th Century, Alfred Rosenberg’s magnum opus, contains not a single reference to the sunken civilization. Throughout millions of recorded statements made by Adolf Hitler from 1919 to 1945, including his voluminous “Table Talk,” the subject appears just twice, and then only in casual after-dinner remarks about the German cosmologist, Hanns Hoerbiger.

Contrary to portrayals by some television producers, Heinrich Himmler never ordered expeditions to search for surviving populations from Atlantis, nor included the study of Atlantis in the curriculum of his SS corps. No prominent Nazi leader ever described Atlantis as the homeland of the Aryan race. Still, the German Navy did name one of it surface raiders the Atlantis, although the name does not otherwise appear to have been used by the Kriegsmarine.

During the 1930s, both German and non-German anthropologists believed the Indo-European peoples originated in either the Steppes of Central Russia or Northern Europe, perhaps a region roughly corresponding to the Baltic States. A volume that did postulate German origins in Atlantis was Unser Ahnen und die Atlanten , Nordliche Seeherrschaft von Skandinavien bis nach Nordafrika (“Our Ancestors and the Atlanteans, Nordic Seamanship from Scandinavia to North Africa” published by Kinkhard and Biermann, Berlin, 1934), by Albert Herrmann (1886-1945). His was principally the examination of an old Frisian manuscript describing survivors from the Atlantis catastrophe in Northern Europe, Nordic maritime technology, and a contemporary discovery in Libya at Schott-el-Djerid, where the concentric ruins of a buried archaeological site suggested Atlantean influences. Nowhere throughout its 164 pages does the author state that either the Atlanteans or the Germans were a “master race.”

Four years after the publication of his popular topic, Herrmann used his prestige as a professor of historical geography at Berlin University to stage a large-scale exhibit about Atlantis in the nation’s capital. Although the 1938 event attracted favorable notice across the country and outside Germany, it was not sponsored by any Nazi organization. He may have contributed to the production of Wo liegt Atlantis? (“Where is Atlantis?”), a popular film examining possible Atlantean impact on Central America, released in 1933, just after the Nazis assumed power. Herrmann’s illustration for Atlantis in Unser Ahnen und die Atlanten, banned in Germany since 1945, is still well-known and continues to be republished in several Atlantology topics, almost invariably without credit.

Other well-known Third Reich Atlantologists included Ernst Moritz Arndt (Nordische Volkskunde, “Nordic Folk Message,” 1935); Alexander Bessmertny (Das Atlantis Raetsel, “TheAtlantis Riddle,” Leipzig, 1932); Rudolf Brunngraber (DerEngel in Atlantis, “The Angel in Atlantis,” Frankfurt, 1938); Heinrich Pudor (Voelker aus altesAthen, Atlantis, Helgoland, “Peoples from old Athens, Atlantis, Helgoland” Leipzig, 1936); Herrmann Wieland (Atlantis, Edda und Bibel, “Atlantis, Edda and the Bible,” Nuremberg, 1922); and Herbert Reichstein (Geloeste Raetsel: Geschichte von Edda, Atlantis und der Bibel, “Solved Riddle: The History of the Edda, Atlantis and the Bible,” Berlin, 1934). They were part of worldwide interest in Atlantis, as attested by contemporary Atlantologists in other countries, such as Britain’s Lewis Spence and Colonel Braghine of the United States. Unfortunately, the works of early 20th-century German Atlantologists, regardless of their political content, were lost when they were uniformly proscribed by Allied occupation authorities after World War II.

Atlantis has always attracted especially broad interest in Germany, as Ignatius Donnelly, the American father of Atlantology, pointed out during the last decade of the 19th century, long prior to Herrmann’s exhibition, and many years before Hitler wrote Mein Kampf. In an attempt to silence their critics, skeptics lump Atlantologists together with “Nazi mass-murderers,” even though consideration of Atlantis, save on a single public occasion (Herrmann’s 1938 exhibit), was never part of the Third Reich.

Thonapa

Either another name for Viracocha, the Andean flood hero, or a distinctly different, though similar, survivor associated with an earlier arrival of technologically gifted foreigners. The Incas told of four major waves of alien immigration to South America during the ancient past, all prompted by terrific natural catastrophes. Thonapa is commonly associated with the Unu-Pachacuti, or “World Over-Turned by Water,” the third Atlantean cataclysm around 1628 b.c.

Thoth

Also known as Thaut (Egyptian), Taaut (Phoenician), Hermes (Greek), and Mercury (Roman), he was mortal, later deified, and a prominent leader of Atlantean refugees into the Nile Valley. He is the Atlantean deity of literature, magic, and healing most associated with civilization. In Greek myth, Hermes is the grandson of Atlas by the Atlantis, Maia. The Theban Recension of the Egyptian topic of the Dead quotes Thaut as having said that the Great Deluge destroyed a former world-class civilization: “I am going to blot out everything which I have made. The Earth shall enter into the waters of the abyss of Nun [the sea-god] by means of a raging flood, and will become even as it was in the primeval time.”

His narration of the catastrophe is related to the Edfu Texts, which locate the “Homeland of the Primeval Ones” on a great island that sank with most of its inhabitants during the Tep Zepi, or “First Time.” Only the gods, led by Thaut, escaped with seven favored sages, who settled at the Nile Delta, where they created Egyptian civilization from a synthesis of Atlantean and native influences. The Edfu Texts are, in this regard at least, in complete accord with Edgar Cayce’s version of events in Egypt at the dawn of pharaonic civilization.

Thule

After Plato’s story of Atlantis became generally known during the early fourth century b.c., a contemporary Greek natural scientist, Pytheas, set out on a voyage of discovery to locate remnants of the sunken civilization. His account, which still exists, tells how he sailed into the Atlantic Ocean, going north toward the Arctic Circle. Historians are uncertain whether Pytheas reached Iceland, the Shetland Islands, or visited Norway’s coast above what is now Bergen. In any case, he called this land Ultima Thule, the “farthest land.” Its native people told him they did indeed know of a great island that had collapsed under the sea many ages ago, when its survivors, their forefathers, sailed north and east to save themselves. The new land was named after their lost homeland, Thule, just as, during the 17th-century, Englishmen arriving from York on the eastern seaboard of North America named their settlement, “New York.”

Tiahuanaco

An Aymara Indian rendition of the older Typi Kala—”Stone-in-the-Center,” in the native Quechua language—suggesting the city’s prominence as an omphalos. “Tiahuanaco” derives from Wanaku, “Powerful Spirit Place,” referring to an island, now sunk beneath nearby Lake Titicaca, formerly the center of the Andean culture-founder Kon-Tiki-Viracocha and his followers. Whether this Aymara tradition refers to Atlantis or the actual stone ruins found beneath the surface of Lake Titicaca, or both, is not clear. The Spanish chronicler, Cieza de Leon, recorded a local Bolivian legend to the effect that “Tiahuanaco was built in a single night after the Flood by unknown giants.”

The ruins comprise an important archaeological site, a pre-Inca ceremonial center, featuring spacious plazas, broad staircases, colossal statuary, and monumental gates.

Tiamuni

The Acomas claimed that their ancestors were white people washed ashore on the east coast of North America by the Deluge. The chief who led these hapless survivors was Tiamuni. The name compares favorably with Tiamat, the Babylonian personification of salt water (the ocean), itself derived from the older Sumerian version. Tiwat was a sun-god of the primordial flood known to the Luvians, a people kindred to the Trojans, in west-coastal Asia Minor.

Tien-Mu

In Chinese myth, a range of mountains far across the Pacific Ocean. According to Churchward, Mu was a mountainous land.

Tien Ti

China’s Imperial Library featured a colossal topic alleged to contain “all knowledge” from ancient times to the 14th century, when additions were still being made. The 4,320-volume set included information about a time when Tien Ti, the Emperor of Heaven—ancient China’s equivalent to Zeus—attempted to wipe out sinful mankind with a worldwide deluge: “The planets altered their courses, the Earth fell to pieces, and the waters in its bosom rushed upwards with violence and overflowed the Earth.”

Another god, Yeu, taking pity on the drowning human beings, caused a giant turtle to rise up from the bottom of the ocean, then transformed the beast into new land. Remarkably, this version is identical to a creation myth repeated by virtually every tribe north of the Rio Grande River. Native American Indians almost universally refer to their continent as “Turtle Island,” after a gigantic turtle raised up from the sea floor by the Great Spirit for their salvation from the Deluge.

Another Chinese text explains how “the pillars supporting the sky crumbled, and the chains from which the Earth was suspended shivered to pieces. Sun, moon, and stars poured down into the northwest, where the sky became low; rivers, seas, and oceans rushed down to the southeast, where the Earth sank. A great conflagration burst out. Flood raged.”

Timaeus

The first of Plato’s Dialogues describing Atlantis. It is presented as a colloquy between Socrates, Hermocrates, Timaeus, and Kritias (whose own Dialogue immediately followed).

In Timaeus, Solon visits the Temple of Neith, in Sais, at the Nile Delta. There, the high priest tells him that 9,000 before, the Athenians saved Mediterranean civilization and Egypt from the invading forces of Atlantis. Located on a large island “beyond the Pillars of Heracles,” or Strait of Gibraltar, the kingdom was greater than Libya and Asia Minor combined, and exercised domination over all neighboring islands, together with the “opposite continent.” The Atlantean sphere of influence stretched eastward as far as Italy and the Libyan border with Egypt. But in the midst of its war with the Greeks, the island of Atlantis sank “in a single day and night” of earthquakes and floods.

The information presented by Timaeus is entirely credible, with most details verified and supported by geology and the traditions of dozens of disparate cultures in the circum-Atlantic region. The only and consistent exception concerns the numerical values applied to Atlantis: they are unmanageably excessive; Atlantis was supposed to have flourished more than 11,000 years ago, its canals were said to be 100 feet deep, and so on. The difficulty is clearly one of translation. The Egyptian high priest who narrated the story spoke in terms of lunar years for the Greeks who knew only solar years. The discrepancy perpetuated itself whenever numerical values were mentioned. Given the common error in translation, the impossible date for Atlantis comes into clearer focus, placing it at the end of the Late Bronze Age, around 1200 b.c.

One of the most revealing details of Timaeus is its mention of the “opposite continent,” an unmistakable reference to America. Its inclusion proves not only that the ancient Greeks knew what lay on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean 2,000 years before Columbus rediscovered it, but underscores the veracity of Plato’s Atlantis account.

Timu

One of five islands among the Maldives at the Equator, located directly south of the Indian subcontinent, named after the lost Pacific civilization of Mu. The Maldives feature numerous stone structures, many of them similar to pyramidal examples in Yucatan, said to have been built long ago by a powerful, seafaring people.

Tiri

Flood-god of Peru’s Pacific coastal Yurukare Indians. They recounted that their ancestors hid in a mountain cave during two worldwide cataclysms that destroyed a former age. All other humans were killed by a fire that fell from the sky, followed by an all-consuming deluge. Tiri alone, of all the other deities, took pity on the survivors of a sinful mankind by opening the Tree of Life, from which new tribes stepped forth to repopulate the world. His myth refers to the destruction of Lemuria, where a sacred tree cult was venerated.

Tir-nan-Og

The Celtic “Island of Youth,” a tradition adopted from pre-Celtic Irish inhabitants and associated with Atlantean invaders of Ireland, the Tuatha da Danann. Its philological correspondence to Homer’s Ogygia, the biblical Og, the Greeks’ Ogygian Flood, and so on, are all transparent references to Atlantis— an identification supported by Tir-nan-Og’s eventual demise beneath the sea. In a Scottish version, Tir-nan-Og was sunk when a wicked servant girl, Bera, the springtime-goddess, uncapped its sacred well. The widespread association of “og” with an Atlantis-like catastrophe defines its impact on various peoples.

Tistar

In the Iranian cosmogony, the Bundahis, an angel personifying Sirius, the Dog Star, battles with the Devil for mastery of the world, shape-shifting from a man and horse to a bull. In these guises, the angelic Tistar creates a month-long deluge, from which the Evil One’s offspring seek refuge in caves. Although the rising waters found them out and drowned them all, their combined venom was so great that it made the ocean salty.

Tistar’s assumed forms suggest the conjunction of constellations at the time of the Great Flood, which is clearly depicted as the result of a major celestial disturbance.

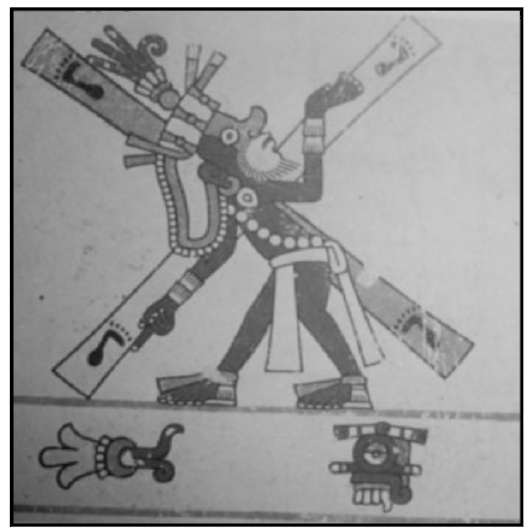

Tlaloc

The Aztec rain-god, portrayed in temple art and illustrated topics as a bearded man supporting the cross of the sky on his shoulders, like the bearded Atlas. According to chronologer, Neil Zimmerer, Tlaloc was originally an Atlantean monarch who improved mining conditions by providing a fresh water system for workers.

Like Atlas, the Aztec Tlaloc carries the cross of the sky on his shoulders.